| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zinc | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | silver-gray | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(Zn) | 65.38(2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zinc in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | post-transition metal, alternatively considered a transition metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell

| 2, 8, 18, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 692.68 K (419.53 °C, 787.15 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1180 K (907 °C, 1665 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 7.14 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 6.57 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 7.32 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 115 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.470 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, 0, +1, +2 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.65 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 134 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 122±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 139 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of zinc | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 3850 m/s (at r.t.) (rolled) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 30.2 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 116 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 59.0 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility | −11.4·10−6 cm3/mol (298 K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 108 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 43 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 70 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 327–412 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-66-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Indian metallurgists (before 1000 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Andreas Sigismund Marggraf (1746) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized as a unique metal by | Rasaratna Samuccaya (800) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of zinc | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zinc is a chemical element with symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is the first element in group 12 of the periodic table. In some respects zinc is chemically similar to magnesium: both elements exhibit only one normal oxidation state (+2), and the Zn2+ and Mg2+ ions are of similar size. Zinc is the 24th most abundant element in Earth's crust and has five stable isotopes. The most common zinc ore is sphalerite (zinc blende), a zinc sulfide mineral. The largest workable lodes are in Australia, Asia, and the United States. Zinc is refined by froth flotation of the ore, roasting, and final extraction using electricity (electrowinning).

Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc in various proportions, was used as early as the third millennium BC in the Aegean, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kalmykia, Turkmenistan and Georgia, and the second millennium BC in West India, Uzbekistan, Iran, Syria, Iraq, and Israel/Palestine. Zinc metal was not produced on a large scale until the 12th century in India, though it was known to the ancient Romans and Greeks. The mines of Rajasthan have given definite evidence of zinc production going back to the 6th century BC. To date, the oldest evidence of pure zinc comes from Zawar, in Rajasthan, as early as the 9th century AD when a distillation process was employed to make pure zinc. Alchemists burned zinc in air to form what they called "philosopher's wool" or "white snow".

The element was probably named by the alchemist Paracelsus after the German word Zinke (prong, tooth). German chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf is credited with discovering pure metallic zinc in 1746. Work by Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta uncovered the electrochemical properties of zinc by 1800. Corrosion-resistant zinc plating of iron (hot-dip galvanizing) is the major application for zinc. Other applications are in electrical batteries, small non-structural castings, and alloys such as brass. A variety of zinc compounds are commonly used, such as zinc carbonate and zinc gluconate (as dietary supplements), zinc chloride (in deodorants), zinc pyrithione (anti-dandruff shampoos), zinc sulfide (in luminescent paints), and dimethylzinc or diethylzinc in the organic laboratory.

Zinc is an essential mineral, including to prenatal and postnatal development. Zinc deficiency affects about two billion people in the developing world and is associated with many diseases. In children, deficiency causes growth retardation, delayed sexual maturation, infection susceptibility, and diarrhea. Enzymes with a zinc atom in the reactive center are widespread in biochemistry, such as alcohol dehydrogenase in humans.

Consumption of excess zinc may cause ataxia, lethargy, and copper deficiency.

Characteristics

Physical properties

Zinc is a bluish-white, lustrous, diamagnetic metal, though most common commercial grades of the metal have a dull finish. It is somewhat less dense than iron and has a hexagonal crystal structure, with a distorted form of hexagonal close packing, in which each atom has six nearest neighbors (at 265.9 pm) in its own plane and six others at a greater distance of 290.6 pm. The metal is hard and brittle at most temperatures but becomes malleable between 100 and 150 °C. Above 210 °C, the metal becomes brittle again and can be pulverized by beating. Zinc is a fair conductor of electricity. For a metal, zinc has relatively low melting (419.5 °C) and boiling points (907 °C). The melting point is the lowest of all the d-block metals aside from mercury and cadmium; for this, among other reasons, zinc, cadmium, and mercury are often not considered to be transition metals like the rest of the d-block metals are.

Many alloys contain zinc, including brass. Other metals long known to form binary alloys with zinc are aluminium, antimony, bismuth, gold, iron, lead, mercury, silver, tin, magnesium, cobalt, nickel, tellurium, and sodium. Although neither zinc nor zirconium are ferromagnetic, their alloy ZrZn

2 exhibits ferromagnetism below 35 K.

2 exhibits ferromagnetism below 35 K.

A bar of zinc generates a characteristic sound when bent, similar to tin cry.

Occurrence

Zinc makes up about 75 ppm (0.0075%) of Earth's crust, making it the 24th most abundant element. Soil contains zinc in 5–770 ppm with an average 64 ppm. Seawater has only 30 ppb and the atmosphere, 0.1–4 µg/m3. The element is normally found in association with other base metals such as copper and lead in ores. Zinc is a chalcophile, meaning the element is more likely to be found in minerals together with sulfur and other heavy chalcogens, rather than with the light chalcogen oxygen or with non-chalcogen electronegative elements such as the halogens. Sulfides formed as the crust solidified under the reducing conditions of the early Earth's atmosphere. Sphalerite, which is a form of zinc sulfide, is the most heavily mined zinc-containing ore because its concentrate contains 60–62% zinc.

Other source minerals for zinc include smithsonite (zinc carbonate), hemimorphite (zinc silicate), wurtzite (another zinc sulfide), and sometimes hydrozincite (basic zinc carbonate). With the exception of wurtzite, all these other minerals were formed by weathering of the primordial zinc sulfides.

Identified world zinc resources total about 1.9–2.8 billion tonnes. Large deposits are in Australia, Canada and the United States, with the largest reserves in Iran.

The most recent estimate of reserve base for zinc (meets specified

minimum physical criteria related to current mining and production

practices) was made in 2009 and calculated to be roughly 480 Mt.

Zinc reserves, on the other hand, are geologically identified ore

bodies whose suitability for recovery is economically based (location,

grade, quality, and quantity) at the time of determination. Since

exploration and mine development is an ongoing process, the amount of

zinc reserves is not a fixed number and sustainability of zinc ore

supplies cannot be judged by simply extrapolating the combined mine life

of today's zinc mines. This concept is well supported by data from the

United States Geological Survey (USGS), which illustrates that although

refined zinc production increased 80% between 1990 and 2010, the reserve

lifetime for zinc has remained unchanged. About 346 million tonnes have

been extracted throughout history to 2002, and scholars have estimated

that about 109–305 million tonnes are in use.

Sphalerite (ZnS)

Isotopes

Five stable isotopes of zinc occur in nature, with 64Zn being the most abundant isotope (49.17% natural abundance). The other isotopes found in nature are 66Zn (27.73%), 67Zn (4.04%), 68Zn (18.45%), and 70Zn (0.61%). The most abundant isotope 64Zn and the rare 70Zn are theoretically unstable on energetic grounds, though their predicted half-lives exceed 4.3×1018 years and 1.3×1016 years, meaning that their radioactivity could be ignored for practical purposes.

Several dozen radioisotopes have been characterized. 65Zn, which has a half-life of 243.66 days, is the least active radioisotope, followed by 72Zn with a half-life of 46.5 hours. Zinc has 10 nuclear isomers. 69mZn has the longest half-life, 13.76 h. The superscript m indicates a metastable isotope. The nucleus of a metastable isotope is in an excited state and will return to the ground state by emitting a photon in the form of a gamma ray. 61Zn has three excited metastable states and 73Zn has two. The isotopes 65Zn, 71Zn, 77Zn and 78Zn each have only one excited metastable state.

The most common decay mode of a radioisotope of zinc with a mass number lower than 66 is electron capture. The decay product resulting from electron capture is an isotope of copper.

- n

30Zn

+

e− → n

29Cu

The most common decay mode of a radioisotope of zinc with mass number higher than 66 is beta decay (β−), which produces an isotope of gallium.

Compounds and chemistry

Reactivity

Zinc has an electron configuration of [Ar]3d104s2 and is a member of the group 12 of the periodic table. It is a moderately reactive metal and strong reducing agent. The surface of the pure metal tarnishes quickly, eventually forming a protective passivating layer of the basic zinc carbonate, Zn

5(OH)

6(CO3)

2, by reaction with atmospheric carbon dioxide. This layer helps prevent further reaction with air and water.

5(OH)

6(CO3)

2, by reaction with atmospheric carbon dioxide. This layer helps prevent further reaction with air and water.

Zinc burns in air with a bright bluish-green flame, giving off fumes of zinc oxide. Zinc reacts readily with acids, alkalis and other non-metals. Extremely pure zinc reacts only slowly at room temperature with acids. Strong acids, such as hydrochloric or sulfuric acid, can remove the passivating layer and subsequent reaction with water releases hydrogen gas.

The chemistry of zinc is dominated by the +2 oxidation state. When compounds in this oxidation state are formed, the outer shell s electrons are lost, yielding a bare zinc ion with the electronic configuration [Ar]3d10. In aqueous solution an octahedral complex, [Zn(H

2O)6]2+ is the predominant species. The volatilization of zinc in combination with zinc chloride at temperatures above 285 °C indicates the formation of Zn

2Cl

2, a zinc compound with a +1 oxidation state. No compounds of zinc in oxidation states other than +1 or +2 are known. Calculations indicate that a zinc compound with the oxidation state of +4 is unlikely to exist.

2O)6]2+ is the predominant species. The volatilization of zinc in combination with zinc chloride at temperatures above 285 °C indicates the formation of Zn

2Cl

2, a zinc compound with a +1 oxidation state. No compounds of zinc in oxidation states other than +1 or +2 are known. Calculations indicate that a zinc compound with the oxidation state of +4 is unlikely to exist.

Zinc chemistry is similar to the chemistry of the late first-row transition metals, nickel and copper, though it has a filled d-shell and compounds are diamagnetic and mostly colorless. The ionic radii of zinc and magnesium happen to be nearly identical. Because of this some of the equivalent salts have the same crystal structure,

and in other circumstances where ionic radius is a determining factor,

the chemistry of zinc has much in common with that of magnesium.

In other respects, there is little similarity with the late first-row

transition metals. Zinc tends to form bonds with a greater degree of covalency and much more stable complexes with N- and S- donors. Complexes of zinc are mostly 4- or 6- coordinate although 5-coordinate complexes are known.

Zinc(I) compounds

Zinc(I)

compounds are rare and need bulky ligands to stabilize the low

oxidation state. Most zinc(I) compounds contain formally the [Zn2]2+ core, which is analogous to the [Hg2]2+ dimeric cation present in mercury(I) compounds. The diamagnetic nature of the ion confirms its dimeric structure. The first zinc(I) compound containing the Zn–Zn bond, (η5-C5Me5)2Zn2, is also the first dimetallocene. The [Zn2]2+ ion rapidly disproportionates

into zinc metal and zinc(II), and has been obtained only a yellow glass

only by cooling a solution of metallic zinc in molten ZnCl2.

Zinc(II) compounds

Zinc acetate

Zinc chloride

Binary compounds of zinc are known for most of the metalloids and all the nonmetals except the noble gases. The oxide ZnO is a white powder that is nearly insoluble in neutral aqueous solutions, but is amphoteric, dissolving in both strong basic and acidic solutions. The other chalcogenides (ZnS, ZnSe, and ZnTe) have varied applications in electronics and optics. Pnictogenides (Zn

3N

2, Zn

3P

2, Zn

3As

2 and Zn

3Sb

2), the peroxide (ZnO

2), the hydride (ZnH

2), and the carbide (ZnC

2) are also known. Of the four halides, ZnF

2 has the most ionic character, while the others (ZnCl

2, ZnBr

2, and ZnI

2) have relatively low melting points and are considered to have more covalent character.

3N

2, Zn

3P

2, Zn

3As

2 and Zn

3Sb

2), the peroxide (ZnO

2), the hydride (ZnH

2), and the carbide (ZnC

2) are also known. Of the four halides, ZnF

2 has the most ionic character, while the others (ZnCl

2, ZnBr

2, and ZnI

2) have relatively low melting points and are considered to have more covalent character.

In weak basic solutions containing Zn2+ ions, the hydroxide Zn(OH)

2 forms as a white precipitate. In stronger alkaline solutions, this hydroxide is dissolved to form zincates ([Zn(OH)4]2−). The nitrate Zn(NO3)

2, chlorate Zn(ClO3)

2, sulfate ZnSO

4, phosphate Zn

3(PO4)

2, molybdate ZnMoO

4, cyanide Zn(CN)

2, arsenite Zn(AsO2)

2, arsenate Zn(AsO4)

2·8H

2O and the chromate ZnCrO

4 (one of the few colored zinc compounds) are a few examples of other common inorganic compounds of zinc. One of the simplest examples of an organic compound of zinc is the acetate (Zn(O

2CCH3)

2).

2 forms as a white precipitate. In stronger alkaline solutions, this hydroxide is dissolved to form zincates ([Zn(OH)4]2−). The nitrate Zn(NO3)

2, chlorate Zn(ClO3)

2, sulfate ZnSO

4, phosphate Zn

3(PO4)

2, molybdate ZnMoO

4, cyanide Zn(CN)

2, arsenite Zn(AsO2)

2, arsenate Zn(AsO4)

2·8H

2O and the chromate ZnCrO

4 (one of the few colored zinc compounds) are a few examples of other common inorganic compounds of zinc. One of the simplest examples of an organic compound of zinc is the acetate (Zn(O

2CCH3)

2).

Organozinc compounds are those that contain zinc–carbon covalent bonds. Diethylzinc ((C

2H5)

2Zn) is a reagent in synthetic chemistry. It was first reported in 1848 from the reaction of zinc and ethyl iodide, and was the first compound known to contain a metal–carbon sigma bond.

2H5)

2Zn) is a reagent in synthetic chemistry. It was first reported in 1848 from the reaction of zinc and ethyl iodide, and was the first compound known to contain a metal–carbon sigma bond.

Test for zinc

Cobalticyanide paper (Rinnmann's test for Zn) can be used as a chemical indicator for zinc. 4 g of K3Co(CN)6 and 1 g of KClO3

is dissolved on 100 ml of water. Paper is dipped in the solution and

dried at 100 °C. One drop of the sample is dropped onto the dry paper

and heated. A green disc indicates the presence of zinc.

History

Ancient use

Late Roman brass bucket – the Hemmoorer Eimer from Warstade, Germany, second to third century AD

Various isolated examples of the use of impure zinc in ancient times

have been discovered. Zinc ores were used to make the zinc–copper alloy brass

thousands of years prior to the discovery of zinc as a separate

element. Judean brass from the 14th to 10th centuries BC contains 23%

zinc.

Knowledge of how to produce brass spread to Ancient Greece by the 7th century BC, but few varieties were made. Ornaments made of alloys containing 80–90% zinc, with lead, iron, antimony, and other metals making up the remainder, have been found that are 2,500 years old. A possibly prehistoric statuette containing 87.5% zinc was found in a Dacian archaeological site.

The oldest known pills were made of the zinc carbonates

hydrozincite and smithsonite. The pills were used for sore eyes and were

found aboard the Roman ship Relitto del Pozzino, wrecked in 140 BC.

The manufacture of brass was known to the Romans by about 30 BC. They made brass by heating powdered calamine (zinc silicate or carbonate), charcoal and copper together in a crucible. The resulting calamine brass was then either cast or hammered into shape for use in weaponry. Some coins struck by Romans in the Christian era are made of what is probably calamine brass.

Strabo writing in the 1st century BC (but quoting a now lost work of the 4th century BC historian Theopompus)

mentions "drops of false silver" which when mixed with copper make

brass. This may refer to small quantities of zinc that is a by-product

of smelting sulfide ores. Zinc in such remnants in smelting ovens was usually discarded as it was thought to be worthless.

The Berne zinc tablet is a votive plaque dating to Roman Gaul made of an alloy that is mostly zinc.

The Charaka Samhita, thought to have been written between 300 and 500 AD, mentions a metal which, when oxidized, produces pushpanjan, thought to be zinc oxide. Zinc mines at Zawar, near Udaipur in India, have been active since the Mauryan period (c. 322 and 187 BCE). The smelting of metallic zinc here, however, appears to have begun around the 12th century AD.

One estimate is that this location produced an estimated million tonnes

of metallic zinc and zinc oxide from the 12th to 16th centuries. Another estimate gives a total production of 60,000 tonnes of metallic zinc over this period. The Rasaratna Samuccaya,

written in approximately the 13th century AD, mentions two types of

zinc-containing ores: one used for metal extraction and another used for

medicinal purposes.

Early studies and naming

Zinc was distinctly recognized as a metal under the designation of Yasada or Jasada in the medical Lexicon ascribed to the Hindu king Madanapala (of Taka dynasty) and written about the year 1374.

Smelting and extraction of impure zinc by reducing calamine with wool

and other organic substances was accomplished in the 13th century in

India. The Chinese did not learn of the technique until the 17th century.

Various alchemical symbols for the element zinc

Alchemists burned zinc metal in air and collected the resulting zinc oxide on a condenser. Some alchemists called this zinc oxide lana philosophica,

Latin for "philosopher's wool", because it collected in wooly tufts,

whereas others thought it looked like white snow and named it nix album.

The name of the metal was probably first documented by Paracelsus, a Swiss-born German alchemist, who referred to the metal as "zincum" or "zinken" in his book Liber Mineralium II, in the 16th century. The word is probably derived from the German zinke, and supposedly meant "tooth-like, pointed or jagged" (metallic zinc crystals have a needle-like appearance). Zink could also imply "tin-like" because of its relation to German zinn meaning tin. Yet another possibility is that the word is derived from the Persian word سنگ seng meaning stone. The metal was also called Indian tin, tutanego, calamine, and spinter.

German metallurgist Andreas Libavius received a quantity of what he called "calay" of Malabar from a cargo ship captured from the Portuguese in 1596.

Libavius described the properties of the sample, which may have been

zinc. Zinc was regularly imported to Europe from the Orient in the 17th

and early 18th centuries, but was at times very expensive.

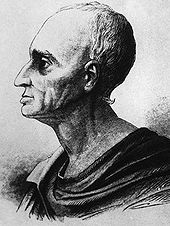

Andreas Sigismund Marggraf is given credit for first isolating pure zinc

Isolation

Metallic zinc was isolated in India by 1300 AD, much earlier than in the West. Before it was isolated in Europe, it was imported from India in about 1600 CE. Postlewayt's Universal Dictionary,

a contemporary source giving technological information in Europe, did

not mention zinc before 1751 but the element was studied before then.

Flemish metallurgist and alchemist P. M. de Respour reported that he had extracted metallic zinc from zinc oxide in 1668. By the start of the 18th century, Étienne François Geoffroy described how zinc oxide condenses as yellow crystals on bars of iron placed above zinc ore that is being smelted. In Britain, John Lane is said to have carried out experiments to smelt zinc, probably at Landore, prior to his bankruptcy in 1726.

In 1738 in Great Britain, William Champion patented a process to extract zinc from calamine in a vertical retort style smelter. His technique resembled that used at Zawar zinc mines in Rajasthan, but no evidence suggests he visited the Orient. Champion's process was used through 1851.

German chemist Andreas Marggraf

normally gets credit for discovering pure metallic zinc, even though

Swedish chemist Anton von Swab had distilled zinc from calamine four

years previously. In his 1746 experiment, Marggraf heated a mixture of calamine and charcoal in a closed vessel without copper to obtain a metal. This procedure became commercially practical by 1752.

Later work

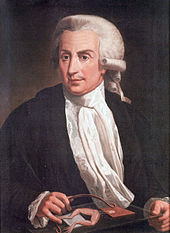

Galvanization was named after Luigi Galvani.

William Champion's brother, John, patented a process in 1758 for calcining zinc sulfide into an oxide usable in the retort process. Prior to this, only calamine could be used to produce zinc. In 1798, Johann Christian Ruberg improved on the smelting process by building the first horizontal retort smelter. Jean-Jacques Daniel Dony built a different kind of horizontal zinc smelter in Belgium that processed even more zinc.

Italian doctor Luigi Galvani discovered in 1780 that connecting the spinal cord of a freshly dissected frog to an iron rail attached by a brass hook caused the frog's leg to twitch. He incorrectly thought he had discovered an ability of nerves and muscles to create electricity and called the effect "animal electricity". The galvanic cell and the process of galvanization were both named for Luigi Galvani, and his discoveries paved the way for electrical batteries, galvanization, and cathodic protection.

Galvani's friend, Alessandro Volta, continued researching the effect and invented the Voltaic pile in 1800. The basic unit of Volta's pile was a simplified galvanic cell, made of plates of copper and zinc separated by an electrolyte

and connected by a conductor externally. The units were stacked in

series to make the Voltaic cell, which produced electricity by directing

electrons from the zinc to the copper and allowing the zinc to corrode.

The non-magnetic character of zinc and its lack of color in

solution delayed discovery of its importance to biochemistry and

nutrition. This changed in 1940 when carbonic anhydrase, an enzyme that scrubs carbon dioxide from blood, was shown to have zinc in its active site. The digestive enzyme carboxypeptidase became the second known zinc-containing enzyme in 1955.

Production

Mining and processing

| Rank | Country | Tonnes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 5,000,000 |

| 2 | Australia | 1,500,000 |

| 3 | Peru | 1,300,000 |

| 4 | India | 820,000 |

| 5 | United States | 700,000 |

| 6 | Mexico | 700,000 |

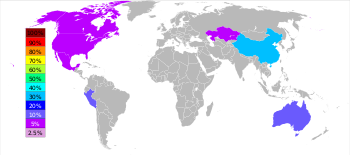

Percentage of zinc output in 2006 by countries

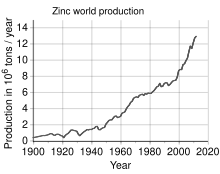

World production trend

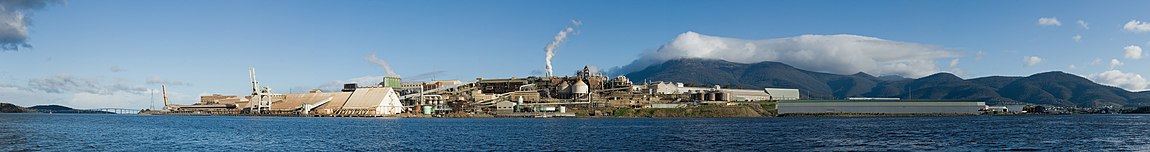

Zinc is the fourth most common metal in use, trailing only iron, aluminium, and copper with an annual production of about 13 million tonnes. The world's largest zinc producer is Nyrstar, a merger of the Australian OZ Minerals and the Belgian Umicore. About 70% of the world's zinc originates from mining, while the remaining 30% comes from recycling secondary zinc. Commercially pure zinc is known as Special High Grade, often abbreviated SHG, and is 99.995% pure.

Worldwide, 95% of new zinc is mined from sulfidic ore deposits, in which sphalerite (ZnS) is nearly always mixed with the sulfides of copper, lead and iron.

Zinc mines are scattered throughout the world, with the main areas

being China, Australia, and Peru. China produced 38% of the global zinc

output in 2014.

Zinc metal is produced using extractive metallurgy. The ore is finely ground, then put through froth flotation to separate minerals from gangue (on the property of hydrophobicity), to get a zinc sulfide ore concentrate consisting of about 50% zinc, 32% sulfur, 13% iron, and 5% SiO

2.

2.

Roasting converts the zinc sulfide concentrate to zinc oxide:

- 2 ZnS + 3 O

2 → 2 ZnO + 2 SO

2

The sulfur dioxide is used for the production of sulfuric acid, which

is necessary for the leaching process. If deposits of zinc carbonate,

zinc silicate, or zinc spinel (like the Skorpion Deposit in Namibia) are used for zinc production, the roasting can be omitted.

For further processing two basic methods are used: pyrometallurgy or electrowinning. Pyrometallurgy reduces zinc oxide with carbon or carbon monoxide

at 950 °C (1,740 °F) into the metal, which is distilled as zinc vapor

to separate it from other metals, which are not volatile at those

temperatures. The zinc vapor is collected in a condenser. The equations below describe this process:

- 2 ZnO + C → 2 Zn + CO

2 - ZnO + CO → Zn + CO

2

In electrowinning, zinc is leached from the ore concentrate by sulfuric acid:

- ZnO + H

2SO

4 → ZnSO

4 + H

2O

Finally, the zinc is reduced by electrolysis.

- 2 ZnSO

4 + 2 H

2O → 2 Zn + 2 H

2SO

4 + O

2

The sulfuric acid is regenerated and recycled to the leaching step.

When galvanised feedstock is fed to an electric arc furnace, the zinc is recovered from the dust by a number of processes, predominately the Waelz process (90% as of 2014).

Environmental impact

Refinement of sulfidic zinc ores produces large volumes of sulfur dioxide and cadmium vapor. Smelter slag

and other residues contain significant quantities of metals. About 1.1

million tonnes of metallic zinc and 130 thousand tonnes of lead were

mined and smelted in the Belgian towns of La Calamine and Plombières between 1806 and 1882. The dumps of the past mining operations leach zinc and cadmium, and the sediments of the Geul River contain non-trivial amounts of metals.

About two thousand years ago, emissions of zinc from mining and

smelting totaled 10 thousand tonnes a year. After increasing 10-fold

from 1850, zinc emissions peaked at 3.4 million tonnes per year in the

1980s and declined to 2.7 million tonnes in the 1990s, although a 2005

study of the Arctic troposphere found that the concentrations there did

not reflect the decline. Anthropogenic and natural emissions occur at a

ratio of 20 to 1.

Zinc in rivers flowing through industrial and mining areas can be as high as 20 ppm. Effective sewage treatment greatly reduces this; treatment along the Rhine, for example, has decreased zinc levels to 50 ppb. Concentrations of zinc as low as 2 ppm adversely affects the amount of oxygen that fish can carry in their blood.

Soils contaminated

with zinc from mining, refining, or fertilizing with zinc-bearing

sludge can contain several grams of zinc per kilogram of dry soil.

Levels of zinc in excess of 500 ppm in soil interfere with the ability

of plants to absorb other essential metals, such as iron and manganese. Zinc levels of 2000 ppm to 180,000 ppm (18%) have been recorded in some soil samples.

Applications

Major applications of zinc include (numbers are given for the US):

- Galvanizing (55%)

- Brass and bronze (16%)

- Other alloys (21%)

- Miscellaneous (8%)

Anti-corrosion and batteries

Hot-dip handrail galvanized crystalline surface

Zinc is most commonly used as an anti-corrosion agent, and galvanization (coating of iron or steel) is the most familiar form. In 2009 in the United States, 55% or 893,000 tons of the zinc metal was used for galvanization.

Zinc is more reactive than iron or steel and thus will attract almost all local oxidation until it completely corrodes away. A protective surface layer of oxide and carbonate (Zn

5(OH)

6(CO

3)

2) forms as the zinc corrodes. This protection lasts even after the zinc layer is scratched but degrades through time as the zinc corrodes away. The zinc is applied electrochemically or as molten zinc by hot-dip galvanizing or spraying. Galvanization is used on chain-link fencing, guard rails, suspension bridges, lightposts, metal roofs, heat exchangers, and car bodies.

5(OH)

6(CO

3)

2) forms as the zinc corrodes. This protection lasts even after the zinc layer is scratched but degrades through time as the zinc corrodes away. The zinc is applied electrochemically or as molten zinc by hot-dip galvanizing or spraying. Galvanization is used on chain-link fencing, guard rails, suspension bridges, lightposts, metal roofs, heat exchangers, and car bodies.

The relative reactivity of zinc and its ability to attract oxidation to itself makes it an efficient sacrificial anode in cathodic protection (CP). For example, cathodic protection of a buried pipeline can be achieved by connecting anodes made from zinc to the pipe. Zinc acts as the anode (negative terminus) by slowly corroding away as it passes electric current to the steel pipeline. Zinc is also used to cathodically protect metals that are exposed to sea water. A zinc disc attached to a ship's iron rudder will slowly corrode while the rudder stays intact.

Similarly, a zinc plug attached to a propeller or the metal protective

guard for the keel of the ship provides temporary protection.

With a standard electrode potential (SEP) of −0.76 volts, zinc is used as an anode material for batteries. (More reactive lithium (SEP −3.04 V) is used for anodes in lithium batteries ). Powdered zinc is used in this way in alkaline batteries and the case (which also serves as the anode) of zinc–carbon batteries is formed from sheet zinc. Zinc is used as the anode or fuel of the zinc-air battery/fuel cell. The zinc-cerium redox flow battery also relies on a zinc-based negative half-cell.

Alloys

A widely

used zinc alloy is brass, in which copper is alloyed with anywhere from

3% to 45% zinc, depending upon the type of brass. Brass is generally more ductile and stronger than copper, and has superior corrosion resistance. These properties make it useful in communication equipment, hardware, musical instruments, and water valves.

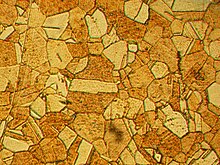

Cast brass microstructure at magnification 400x

Other widely used zinc alloys include nickel silver, typewriter metal, soft and aluminium solder, and commercial bronze. Zinc is also used in contemporary pipe organs as a substitute for the traditional lead/tin alloy in pipes.

Alloys of 85–88% zinc, 4–10% copper, and 2–8% aluminium find limited

use in certain types of machine bearings. Zinc is the primary metal in American one cent coins (pennies) since 1982.

The zinc core is coated with a thin layer of copper to give the

appearance of a copper coin. In 1994, 33,200 tonnes (36,600 short tons)

of zinc were used to produce 13.6 billion pennies in the United States.

Alloys of zinc with small amounts of copper, aluminium, and magnesium are useful in die casting as well as spin casting, especially in the automotive, electrical, and hardware industries. These alloys are marketed under the name Zamak. An example of this is zinc aluminium. The low melting point together with the low viscosity

of the alloy makes possible the production of small and intricate

shapes. The low working temperature leads to rapid cooling of the cast

products and fast production for assembly.

Another alloy, marketed under the brand name Prestal, contains 78% zinc

and 22% aluminium, and is reported to be nearly as strong as steel but

as malleable as plastic. This superplasticity of the alloy allows it to be molded using die casts made of ceramics and cement.

Similar alloys with the addition of a small amount of lead can be

cold-rolled into sheets. An alloy of 96% zinc and 4% aluminium is used

to make stamping dies for low production run applications for which

ferrous metal dies would be too expensive. For building facades, roofing, and other applications for sheet metal formed by deep drawing, roll forming, or bending, zinc alloys with titanium and copper are used. Unalloyed zinc is too brittle for these manufacturing processes.

As a dense, inexpensive, easily worked material, zinc is used as a lead replacement. In the wake of lead concerns, zinc appears in weights for various applications ranging from fishing to tire balances and flywheels.

Cadmium zinc telluride (CZT) is a semiconductive alloy that can be divided into an array of small sensing devices. These devices are similar to an integrated circuit and can detect the energy of incoming gamma ray photons. When behind an absorbing mask, the CZT sensor array can determine the direction of the rays.

Other industrial uses

Roughly one quarter of all zinc output in the United States in 2009 was consumed in zinc compounds; a variety of which are used industrially. Zinc oxide is widely used as a white pigment in paints and as a catalyst in the manufacture of rubber to disburse heat. Zinc oxide is used to protect rubber polymers and plastics from ultraviolet radiation (UV). The semiconductor properties of zinc oxide make it useful in varistors and photocopying products. The zinc zinc-oxide cycle is a two step thermochemical process based on zinc and zinc oxide for hydrogen production.

Zinc chloride is often added to lumber as a fire retardant and sometimes as a wood preservative. It is used in the manufacture of other chemicals. Zinc methyl (Zn(CH3)

2) is used in a number of organic syntheses. Zinc sulfide (ZnS) is used in luminescent pigments such as on the hands of clocks, X-ray and television screens, and luminous paints. Crystals of ZnS are used in lasers that operate in the mid-infrared part of the spectrum. Zinc sulfate is a chemical in dyes and pigments. Zinc pyrithione is used in antifouling paints.

2) is used in a number of organic syntheses. Zinc sulfide (ZnS) is used in luminescent pigments such as on the hands of clocks, X-ray and television screens, and luminous paints. Crystals of ZnS are used in lasers that operate in the mid-infrared part of the spectrum. Zinc sulfate is a chemical in dyes and pigments. Zinc pyrithione is used in antifouling paints.

Zinc powder is sometimes used as a propellant in model rockets. When a compressed mixture of 70% zinc and 30% sulfur powder is ignited there is a violent chemical reaction. This produces zinc sulfide, together with large amounts of hot gas, heat, and light.

Zinc sheet metal is used to make zinc bars.

64Zn, the most abundant isotope of zinc, is very susceptible to neutron activation, being transmuted into the highly radioactive 65Zn, which has a half-life of 244 days and produces intense gamma radiation. Because of this, zinc oxide used in nuclear reactors as an anti-corrosion agent is depleted of 64Zn before use, this is called depleted zinc oxide. For the same reason, zinc has been proposed as a salting material for nuclear weapons (cobalt is another, better-known salting material). A jacket of isotopically enriched 64Zn would be irradiated by the intense high-energy neutron flux from an exploding thermonuclear weapon, forming a large amount of 65Zn significantly increasing the radioactivity of the weapon's fallout. Such a weapon is not known to have ever been built, tested, or used.

65Zn is used as a tracer to study how alloys that contain zinc wear out, or the path and the role of zinc in organisms.

Zinc dithiocarbamate complexes are used as agricultural fungicides; these include Zineb, Metiram, Propineb and Ziram. Zinc naphthenate is used as wood preservative. Zinc in the form of ZDDP, is used as an anti-wear additive for metal parts in engine oil.

Organic chemistry

Addition of diphenylzinc to an aldehyde

Organozinc

chemistry is the science of compounds that contain carbon-zinc bonds,

describing the physical properties, synthesis, and chemical

reactions.Many organozinc compounds are important. Among important applications are:

- The Frankland-Duppa Reaction in which an oxalate ester (ROCOCOOR) reacts with an alkyl halide R'X, zinc and hydrochloric acid to form the α-hydroxycarboxylic esters RR'COHCOOR

- The Reformatskii reaction in which α-halo-esters and aldehydes are converted to β-hydroxy-esters

- The Simmons–Smith reaction in which the carbenoid (iodomethyl)zinc iodide reacts with alkene(or alkyne) and converts them to cyclopropane

- The Addition reaction of organozinc compounds to form carbonyl compounds

- The Barbier reaction (1899), which is the zinc equivalent of the magnesium Grignard reaction and is the better of the two. In presence of water, formation of the organomagnesium halide will fail, whereas the Barbier reaction can take place in water.

- On the downside, organozincs are much less nucleophilic than Grignards, and they are expensive and difficult to handle. Commercially available diorganozinc compounds are dimethylzinc, diethylzinc and diphenylzinc. In one study, the active organozinc compound is obtained from much cheaper organobromine precursors

- The Negishi coupling is also an important reaction for the formation of new carbon-carbon bonds between unsaturated carbon atoms in alkenes, arenes and alkynes. The catalysts are nickel and palladium. A key step in the catalytic cycle is a transmetalation in which a zinc halide exchanges its organic substituent for another halogen with the palladium (nickel) metal center.

- The Fukuyama coupling is another coupling reaction, but it uses a thioester as reactant and produces a ketone.

Zinc has found many applications as catalyst in organic synthesis

including asymmetric synthesis, being cheap and easily available

alternative to precious metal complexes. The results (yield and ee)

obtained with chiral zinc catalysts are comparable to those achieved

with palladium, ruthenium, iridium and others, and zinc becomes metal

catalyst of choice.

Dietary supplement

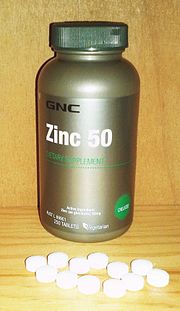

GNC

zinc 50 mg tablets. The amount exceeds what is deemed the safe upper

limit in the United States (40 mg) and European Union (25 mg)

Zinc gluconate is one compound used for the delivery of zinc as a dietary supplement.

In most single-tablet, over-the-counter, daily vitamin and mineral supplements, zinc is included in such forms as zinc oxide, zinc acetate, or zinc gluconate.

Zinc is generally considered to be an antioxidant. However, it is redox

inert and thus can serve such a function only indirectly.

Generally, zinc supplement is recommended where there is high risk of

zinc deficiency (such as low and middle income countries) as a

preventive measure.

Zinc deficiency has been associated with major depressive disorder (MDD), and zinc supplements may be an effective treatment.

Zinc serves as a simple, inexpensive, and critical tool for

treating diarrheal episodes among children in the developing world. Zinc

becomes depleted in the body during diarrhea,

but recent studies suggest that replenishing zinc with a 10- to 14-day

course of treatment can reduce the duration and severity of diarrheal

episodes and may also prevent future episodes for as long as three

months.

A Cochrane review stated that people taking zinc supplement may be less likely to progress to age-related macular degeneration.

Zinc supplement is an effective treatment for acrodermatitis enteropathica, a genetic disorder affecting zinc absorption that was previously fatal to affected infants.

Gastroenteritis is strongly attenuated by ingestion of zinc, possibly by direct antimicrobial action of the ions in the gastrointestinal tract, or by the absorption of the zinc and re-release from immune cells (all granulocytes secrete zinc), or both.

In 2011, researchers reported that adding large amounts of zinc

to a urine sample masked detection of drugs. The researchers did not

test whether orally consuming a zinc dietary supplement could have the

same effect.

Zinc is a negative allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor.

Common cold

Zinc supplements (frequently zinc acetate or zinc gluconate lozenges) are a group of dietary supplements that are commonly used for the treatment of the common cold.

The use of zinc supplements at doses in excess of 75 mg/day within

24 hours of the onset of symptoms has been shown to reduce the duration

of cold symptoms by about 1 day. Due to a lack of data, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether the preventative use of zinc supplements reduces the likelihood of contracting a cold. Adverse effects with zinc supplements by mouth include bad taste and nausea. The intranasal use of zinc-containing nasal sprays has been associated with the loss of the sense of smell; consequently, in June 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) warned consumers to stop using intranasal zinc products.

The human rhinovirus – the most common viral pathogen in humans – is the predominant cause of the common cold. The hypothesized mechanism of action by which zinc reduces the severity and/or duration of cold symptoms is the suppression of nasal inflammation and the direct inhibition of rhinoviral receptor binding and rhinoviral replication in the nasal mucosa.

Topical use

Topical preparations of zinc include those used on the skin, often in the form of zinc oxide. Zinc preparations can protect against sunburn in the summer and windburn in the winter. Applied thinly to a baby's diaper area (perineum) with each diaper change, it can protect against diaper rash.

Chelated zinc is used in toothpastes and mouthwashes to prevent bad breath.

Zinc pyrithione is widely included in shampoos to prevent dandruff.

Biological role

Zinc is an essential trace element for humans and other animals, for plants and for microorganisms. Zinc is required for the function of over 300 enzymes and 1000 transcription factors, and is stored and transferred in metallothioneins. It is the second most abundant trace metal in humans after iron and it is the only metal which appears in all enzyme classes.

In proteins, zinc ions are often coordinated to the amino acid side chains of aspartic acid, glutamic acid, cysteine and histidine.

The theoretical and computational description of this zinc binding in

proteins (as well as that of other transition metals) is difficult.

Roughly 2–4 grams of zinc

are distributed throughout the human body. Most zinc is in the brain,

muscle, bones, kidney, and liver, with the highest concentrations in the

prostate and parts of the eye. Semen is particularly rich in zinc, a key factor in prostate gland function and reproductive organ growth.

Zinc homeostasis of the body is mainly controlled by the intestine. Here, ZIP4 and especially TRPM7 were linked to intestinal zinc uptake essential for postnatal survival.

In humans, the biological roles of zinc are ubiquitous. It interacts with "a wide range of organic ligands", and has roles in the metabolism of RNA and DNA, signal transduction, and gene expression. It also regulates apoptosis.

A 2006 study estimated that about 10% of human proteins (2800)

potentially bind zinc, in addition to hundreds more that transport and

traffic zinc; a similar in silico study in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana found 2367 zinc-related proteins.

In the brain, zinc is stored in specific synaptic vesicles by glutamatergic neurons and can modulate neuronal excitability. It plays a key role in synaptic plasticity and so in learning. Zinc homeostasis also plays a critical role in the functional regulation of the central nervous system. Dysregulation of zinc homeostasis in the central nervous system that

results in excessive synaptic zinc concentrations is believed to induce neurotoxicity through mitochondrial oxidative stress (e.g., by disrupting certain enzymes involved in the electron transport chain, including complex I, complex III, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase), the dysregulation of calcium homeostasis, glutamatergic neuronal excitotoxicity, and interference with intraneuronal signal transduction. L- and D-histidine facilitate brain zinc uptake. SLC30A3 is the primary zinc transporter involved in cerebral zinc homeostasis.

Enzymes

Ribbon diagram of human carbonic anhydrase II, with zinc atom visible in the center

Zinc fingers help read DNA sequences.

Zinc is an efficient Lewis acid, making it a useful catalytic agent in hydroxylation and other enzymatic reactions. The metal also has a flexible coordination geometry, which allows proteins using it to rapidly shift conformations to perform biological reactions. Two examples of zinc-containing enzymes are carbonic anhydrase and carboxypeptidase, which are vital to the processes of carbon dioxide (CO

2) regulation and digestion of proteins, respectively.

2) regulation and digestion of proteins, respectively.

In vertebrate blood, carbonic anhydrase converts CO

2 into bicarbonate and the same enzyme transforms the bicarbonate back into CO

2 for exhalation through the lungs. Without this enzyme, this conversion would occur about one million times slower at the normal blood pH of 7 or would require a pH of 10 or more. The non-related β-carbonic anhydrase is required in plants for leaf formation, the synthesis of indole acetic acid (auxin) and alcoholic fermentation.

2 into bicarbonate and the same enzyme transforms the bicarbonate back into CO

2 for exhalation through the lungs. Without this enzyme, this conversion would occur about one million times slower at the normal blood pH of 7 or would require a pH of 10 or more. The non-related β-carbonic anhydrase is required in plants for leaf formation, the synthesis of indole acetic acid (auxin) and alcoholic fermentation.

Carboxypeptidase cleaves peptide linkages during digestion of proteins. A coordinate covalent bond

is formed between the terminal peptide and a C=O group attached to

zinc, which gives the carbon a positive charge. This helps to create a hydrophobic pocket on the enzyme near the zinc, which attracts the non-polar part of the protein being digested.

Signalling

Zinc

has been recognized as a messenger, able to activate signalling

pathways. Many of these pathways provide the driving force in aberrant

cancer growth. They can be targeted through ZIP transporters.

Other proteins

Zinc serves a purely structural role in zinc fingers, twists and clusters. Zinc fingers form parts of some transcription factors, which are proteins that recognize DNA base sequences during the replication and transcription of DNA. Each of the nine or ten Zn2+ ions in a zinc finger helps maintain the finger's structure by coordinately binding to four amino acids in the transcription factor. The transcription factor wraps around the DNA helix and uses its fingers to accurately bind to the DNA sequence.

In blood plasma, zinc is bound to and transported by albumin (60%, low-affinity) and transferrin (10%).

Because transferrin also transports iron, excessive iron reduces zinc

absorption, and vice versa. A similar antagonism exists with copper. The concentration of zinc in blood plasma stays relatively constant regardless of zinc intake. Cells in the salivary gland, prostate, immune system, and intestine use zinc signaling to communicate with other cells.

Zinc may be held in metallothionein reserves within microorganisms or in the intestines or liver of animals. Metallothionein in intestinal cells is capable of adjusting absorption of zinc by 15–40%.

However, inadequate or excessive zinc intake can be harmful; excess

zinc particularly impairs copper absorption because metallothionein

absorbs both metals.

The human dopamine transporter contains a high affinity extracellular zinc binding site which, upon zinc binding, inhibits dopamine reuptake and amplifies amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux in vitro. The human serotonin transporter and norepinephrine transporter do not contain zinc binding sites. Some EF-hand calcium binding proteins such as S100 or NCS-1 are also able to bind zinc ions.

Dietary recommendations

The

U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) updated Estimated Average Requirements

(EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for zinc in 2001. The

current EARs for zinc for women and men ages 14 and up is 6.8 and

9.4 mg/day, respectively. The RDAs are 8 and 11 mg/day. RDAs are higher

than EARs so as to identify amounts that will cover people with higher

than average requirements. RDA for pregnancy is 11 mg/day. RDA for

lactation is 12 mg/day. For infants up to 12 months the RDA is 3 mg/day.

For children ages 1–13 years the RDA increases with age from 3 to

8 mg/day. As for safety, the IOM sets Tolerable upper intake levels

(ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. In the

case of zinc the adult UL is 40 mg/day (lower for children).

Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs).

The European Food Safety Authority

(EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference

Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and

Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL are defined the same as in

United States. For people ages 18 and older the PRI calculations are

complex, as the EFSA has set higher and higher values as the phytate

content of the diet increases. For women, PRIs increase from 7.5 to

12.7 mg/day as phytate intake increases from 300 to 1200 mg/day; for men

the range is 9.4 to 16.3 mg/day. These PRIs are higher than the U.S.

RDAs. The EFSA reviewed the same safety question and set its UL at 25 mg/day, which is much lower than the U.S. value.

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount

in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For zinc

labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was 15 mg, but on May 27, 2016

it was revised to 11 mg. A table of the old and new adult Daily Values is provided at Reference Daily Intake. Food and supplement companies have until January 1, 2020 to comply with the change.

Dietary intake

Foods and spices containing zinc

Animal products such as meat, fish, shellfish, fowl, eggs, and dairy

contain zinc. The concentration of zinc in plants varies with the level

in the soil. With adequate zinc in the soil, the food plants that

contain the most zinc are wheat (germ and bran) and various seeds,

including sesame, poppy, alfalfa, celery, and mustard. Zinc is also found in beans, nuts, almonds, whole grains, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, and blackcurrant. Plant phytates are particularly found in pulses and cereals and interfere with zinc absorption.

Other sources include fortified food and dietary supplements

in various forms. A 1998 review concluded that zinc oxide, one of the

most common supplements in the United States, and zinc carbonate are

nearly insoluble and poorly absorbed in the body.

This review cited studies that found lower plasma zinc concentrations

in the subjects who consumed zinc oxide and zinc carbonate than in those

who took zinc acetate and sulfate salts.

For fortification, however, a 2003 review recommended cereals

(containing zinc oxide) as a cheap, stable source that is as easily

absorbed as the more expensive forms.

A 2005 study found that various compounds of zinc, including oxide and

sulfate, did not show statistically significant differences in

absorption when added as fortificants to maize tortillas.

Deficiency

Nearly two billion people in the developing world are deficient in

zinc. Groups at risk include children in developing countries and

elderly with chronic illnesses.

In children, it causes an increase in infection and diarrhea and

contributes to the death of about 800,000 children worldwide per year. The World Health Organization advocates zinc supplementation for severe malnutrition and diarrhea. Zinc supplements help prevent disease and reduce mortality, especially among children with low birth weight or stunted growth.

However, zinc supplements should not be administered alone, because

many in the developing world have several deficiencies, and zinc

interacts with other micronutrients. While zinc deficiency is usually due to insufficient dietary intake, it can be associated with malabsorption, acrodermatitis enteropathica, chronic liver disease, chronic renal disease, sickle cell disease, diabetes, malignancy, and other chronic illnesses.

In the United States, a federal survey of food consumption

determined that for women and men over the age of 19, average

consumption was 9.7 and 14.2 mg/day, respectively. For women, 17%

consumed less than the EAR, for men 11%. The percentages below EAR

increased with age.

The most recent published update of the survey (NHANES 2013–2014)

reported lower averages – 9.3 and 13.2 mg/day – again with intake

decreasing with age.

Symptoms of mild zinc deficiency are diverse. Clinical outcomes include depressed growth, diarrhea, impotence and delayed sexual maturation, alopecia,

eye and skin lesions, impaired appetite, altered cognition, impaired

immune functions, defects in carbohydrate utilization, and reproductive teratogenesis. Zinc deficiency depresses immunity, but excessive zinc does also.

Despite some concerns, western vegetarians and vegans do not suffer any more from overt zinc deficiency than meat-eaters. Major plant sources of zinc include cooked dried beans, sea vegetables, fortified cereals, soy foods, nuts, peas, and seeds. However, phytates

in many whole-grains and fibers may interfere with zinc absorption and

marginal zinc intake has poorly understood effects. The zinc chelator phytate, found in seeds and cereal bran, can contribute to zinc malabsorption.

Some evidence suggests that more than the US RDA (8 mg/day for adult

women; 11 mg/day for adult men) may be needed in those whose diet is

high in phytates, such as some vegetarians. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidelines attempt to compensate for this by recommending higher zinc intake when dietary phytate intake is greater. These considerations must be balanced against the paucity of adequate zinc biomarkers, and the most widely used indicator, plasma zinc, has poor sensitivity and specificity.

Soil remediation

Species of Calluna, Erica and Vaccinium can grow in zinc metalliferous soils, because translocation of toxic ions is prevented by the action of ericoid mycorrhizal fungi.

Agriculture

Zinc

deficiency appears to be the most common micronutrient deficiency in

crop plants; it is particularly common in high-pH soils. Zinc-deficient soil is cultivated

in the cropland of about half of Turkey and India, a third of China,

and most of Western Australia. Substantial responses to zinc

fertilization have been reported in these areas.

Plants that grow in soils that are zinc-deficient are more susceptible

to disease. Zinc is added to the soil primarily through the weathering

of rocks, but humans have added zinc through fossil fuel combustion,

mine waste, phosphate fertilizers, pesticide (zinc phosphide),

limestone, manure, sewage sludge, and particles from galvanized

surfaces. Excess zinc is toxic to plants, although zinc toxicity is far

less widespread.

Precautions

Toxicity

Although

zinc is an essential requirement for good health, excess zinc can be

harmful. Excessive absorption of zinc suppresses copper and iron

absorption. The free zinc ion in solution is highly toxic to plants, invertebrates, and even vertebrate fish. The Free Ion Activity Model is well-established in the literature, and shows that just micromolar amounts of the free ion kills some organisms. A recent example showed 6 micromolar killing 93% of all Daphnia in water.

The free zinc ion is a powerful Lewis acid up to the point of being corrosive. Stomach acid contains hydrochloric acid, in which metallic zinc dissolves readily to give corrosive zinc chloride. Swallowing a post-1982 American one cent piece (97.5% zinc) can cause damage to the stomach lining through the high solubility of the zinc ion in the acidic stomach.

Evidence shows that people taking 100–300 mg of zinc daily may suffer induced copper deficiency.

A 2007 trial observed that elderly men taking 80 mg daily were

hospitalized for urinary complications more often than those taking a

placebo. Levels of 100–300 mg may interfere with the utilization of copper and iron or adversely affect cholesterol. Zinc in excess of 500 ppm in soil interferes with the plant absorption of other essential metals, such as iron and manganese. A condition called the zinc shakes or "zinc chills" can be induced by inhalation of zinc fumes while brazing or welding galvanized materials. Zinc is a common ingredient of denture

cream which may contain between 17 and 38 mg of zinc per gram.

Disability and even deaths from excessive use of these products have

been claimed.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that zinc damages nerve receptors in the nose, causing anosmia. Reports of anosmia were also observed in the 1930s when zinc preparations were used in a failed attempt to prevent polio infections.

On June 16, 2009, the FDA ordered removal of zinc-based intranasal cold

products from store shelves. The FDA said the loss of smell can be

life-threatening because people with impaired smell cannot detect

leaking gas or smoke, and cannot tell if food has spoiled before they

eat it.

Recent research suggests that the topical antimicrobial zinc pyrithione is a potent heat shock response inducer that may impair genomic integrity with induction of PARP-dependent energy crisis in cultured human keratinocytes and melanocytes.

Poisoning

In 1982, the US Mint began minting pennies

coated in copper but containing primarily zinc. Zinc pennies pose a

risk of zinc toxicosis, which can be fatal. One reported case of chronic

ingestion of 425 pennies (over 1 kg of zinc) resulted in death due to

gastrointestinal bacterial and fungal sepsis. Another patient who ingested 12 grams of zinc showed only lethargy and ataxia (gross lack of coordination of muscle movements). Several other cases have been reported of humans suffering zinc intoxication by the ingestion of zinc coins.

Pennies and other small coins are sometimes ingested by dogs,

requiring veterinary removal of the foreign objects. The zinc content of

some coins can cause zinc toxicity, commonly fatal in dogs through

severe hemolytic anemia and liver or kidney damage; vomiting and diarrhea are possible symptoms. Zinc is highly toxic in parrots and poisoning can often be fatal. The consumption of fruit juices stored in galvanized cans has resulted in mass parrot poisonings with zinc.