Louis Agassiz

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 28, 1807

Haut-Vully, Switzerland

|

| Died | December 14, 1873 (aged 66) |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | University of Erlangen-Nuremberg |

| Known for | Polygenism |

| Spouse(s) | Cecilie Braun Elizabeth Cabot Cary |

| Children | Alexander, Ida, and Pauline |

| Awards | Wollaston Medal (1836) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | University of Neuchâtel Harvard University Cornell University |

| Doctoral advisor | Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius |

| Other academic advisors | Ignaz Döllinger, Georges Cuvier, Alexander von Humboldt |

| Notable students | William Stimpson, William Healey Dall, Karl Vogt |

| Signature | |

| |

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz was a Swiss-American biologist and geologist recognized as an innovative and prodigious scholar of Earth's natural history. Agassiz grew up in Switzerland. He received Doctor of Philosophy and medical degrees at Erlangen and Munich, respectively. After studying with Cuvier and Humboldt in Paris, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel. He emigrated to the United States in 1847 after visiting Harvard University. He went on to become professor of zoology and geology at Harvard, to head its Lawrence Scientific School, and to found its Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Agassiz is known for his regimen of observational data gathering and analysis. He made vast institutional and scientific contributions to zoology, geology, and related areas, including writing multi-volume research books running to thousands of pages. He is particularly known for his contributions to ichthyological classification, including of extinct species, and to the study of geological history, including to the founding of glaciology. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Agassiz's resistance to Darwinian evolution, belief in creationism, and the scientific racism implicit in his writings on human polygenism, have tarnished his reputation and led to controversies over his legacy.

Early life

Louis Agassiz was born in Môtier (now part of Haut-Vully) in the Swiss canton of Fribourg. The son of a pastor, Agassiz was educated first at home, he then spent four years of secondary school in Bienne, entering in 1818 and completing his elementary studies in Lausanne. Agassiz studied successively at the universities of Zürich, Heidelberg, and Munich; while there, he extended his knowledge of natural history, especially of botany. In 1829 he received the degree of doctor of philosophy at Erlangen, and in 1830 that of doctor of medicine at Munich. Moving to Paris, he came under the tutelage of Alexander von Humboldt (and later his financial benevolence). Humboldt and Georges Cuvier launched him on his careers of geology and zoology respectively. Ichthyology soon became a focus of his life's work.

Work

Agassiz in 1870

In 1819–1820, the German biologists Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius undertook an expedition to Brazil. They returned home to Europe with many natural objects, including an important collection of the freshwater fish of Brazil, especially of the Amazon River.

Spix, who died in 1826, did not live long enough to work out the

history of these fish, and Martius selected Agassiz for this project.

Agassiz threw himself into the work with an enthusiasm that would go on

to characterize the rest of life's work. The task of describing the

Brazilian fish was completed and published in 1829. This was followed by

research into the history of fish found in Lake Neuchâtel. Enlarging his plans, in 1830 he issued a prospectus of a History of the Freshwater Fish of Central Europe. It was only in 1839, however, that the first part of this publication appeared, and it was completed in 1842.

In 1832, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel. The fossil fish in the rock of the surrounding region, the slates of Glarus and the limestones of Monte Bolca,

soon attracted his attention. At the time, very little had been

accomplished in their scientific study. Agassiz, as early as 1829,

planned the publication of a work which, more than any other, laid the

foundation of his worldwide fame. Five volumes of his Recherches sur les poissons fossiles ("Research on Fossil Fish") were published from 1833 to 1843. They were magnificently illustrated, chiefly by Joseph Dinkel.

In gathering materials for this work Agassiz visited the principal

museums in Europe, and, meeting Cuvier in Paris, he received much

encouragement and assistance from him. They had known him for seven years at the time.

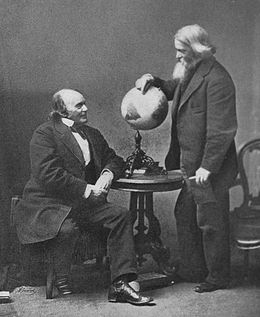

With Benjamin Peirce

Agassiz found that his palaeontological analyses required a new

ichthyological classification. The fossils he examined rarely showed any

traces of the soft tissues of fish, but, instead, consisted chiefly of

the teeth, scales, and fins, with the bones being perfectly preserved in

comparatively few instances. He, therefore, adopted a classification

that divided fish into four groups: Ganoids, Placoids, Cycloids and

Ctenoids, based on the nature of the scales and other dermal appendages.

This did much to improve fish taxonomy, but Aggasiz's classification has since been superseded.

Agassiz needed financial support to continue his work. The British Association and the Earl of Ellesmere—then Lord Francis Egerton—stepped in to help. The 1,290 original drawings made for the work were purchased by the Earl, and presented by him to the Geological Society of London. In 1836, the Wollaston Medal

was awarded to Agassiz by the council of that society for his work on

fossil ichthyology; and, in 1838, he was elected a foreign member of the

Royal Society. Meanwhile, invertebrate animals engaged his attention. In 1837, he issued the "Prodrome" of a monograph on the recent and fossil Echinodermata,

the first part of which appeared in 1838; in 1839–40, he published two

quarto volumes on the fossil Echinoderms of Switzerland; and in 1840–45

he issued his Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles ("Critical Studies on Fossil Mollusks").

Before Agassiz's first visit to England in 1834, Hugh Miller and other geologists had brought to light the remarkable fossil fish of the Old Red Sandstone of the northeast of Scotland. The strange forms of the Pterichthys, the Coccosteus

and other genera were then made known to geologists for the first time.

They were of intense interest to Agassiz, and formed the subject of a

monograph by him published in 1844–45: Monographie des poissons

fossiles du Vieux Grès Rouge, ou Système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone)

des Îles Britanniques et de Russie ("Monograph on Fossil Fish of the Old Red Sandstone, or Devonian System of the British Isles and of Russia").

In the early stages of his career in Neuchatel, Agassiz also made a

name for himself as a man who could run a scientific department well.

Under his care, the University of Neuchâtel soon became a leading

institution for scientific inquiry.

Portrait photograph by John Adams Whipple, c. 1865

In 1842–1846, Agassiz issued his Nomenclator Zoologicus, a classification list, with references, of all names used in zoological genera and groups.

Ice age

In 1837, Agassiz proposed that the Earth had been subjected to a past ice age. He presented the theory to the Helvetic Society

that ancient glaciers had not only flowed outward from the Alps, but

that even larger glaciers had covered the plains and mountains of

Europe, Asia, and North America, smothering the entire northern hemisphere in a prolonged ice age. In the same year, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Prior to this proposal, Goethe, de Saussure, Venetz, Jean de Charpentier, Karl Friedrich Schimper and others had studied the glaciers of the Alps, and Goethe, Charpentier and Schimper had even concluded that the erratic blocks of alpine rocks scattered over the slopes and summits of the Jura Mountains

had been moved there by glaciers. These ideas attracted the attention

of Agassiz, and he discussed them with Charpentier and Schimper, whom he

accompanied on successive trips to the Alps. Agassiz even had a hut

constructed upon one of the Aar Glaciers, which for a time he made his home, to investigate the structure and movements of the ice.

In 1840, Agassiz published a two-volume work entitled Études sur les glaciers ("Studies on Glaciers"). In this, he discussed the movements of the glaciers, their moraines, their influence in grooving and rounding the rocks, and in producing the striations and roches moutonnees

seen in Alpine-style landscapes. He accepted Charpentier's and

Schimper's idea that some of the alpine glaciers had extended across the

wide plains and valleys of the Aar and Rhône.

But he went further, concluding that, in the recent past, Switzerland

had been covered with one vast sheet of ice, originating in the higher

Alps and extending over the valley of northwestern Switzerland to

southern slopes of the Jura. The publication of this work gave fresh

impetus to the study of glacial phenomena in all parts of the world.

Familiar, then, with recent glaciation, Agassiz and the English geologist William Buckland

visited the mountains of Scotland in 1840. There they found clear

evidence in different locations of glacial action. The discovery was

announced to the Geological Society of London in successive

communications. The mountainous districts of England, Wales, and Ireland

were understood to have been centres for the dispersion of glacial

debris. Agassiz remarked "that great sheets of ice, resembling those now

existing in Greenland, once covered all the countries in which

unstratified gravel (boulder drift) is found; that this gravel was in

general produced by the trituration of the sheets of ice upon the subjacent surface, etc."

The man-sized iron auger used by Agassiz to drill up to 7.5 metres deep into the Unteraar Glacier to take its temperature.

United States

With the aid of a grant of money from the King of Prussia, Agassiz crossed the Atlantic

in the autumn of 1846 to investigate the natural history and geology of

North America and to deliver a course of lectures on "The Plan of

Creation as shown in the Animal Kingdom," by invitation from J. A. Lowell, at the Lowell Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

The financial offers presented to him in the United States induced him

to settle there, where he remained to the end of his life. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1846. Agassiz had a cordial relationship with Harvard botanist Asa Gray, but they disagreed on some scientific issues. For example, Agassiz was a member of the Scientific Lazzaroni,

a group of mostly physical scientists who wanted American academia to

mimic the autocratic academic structures of European universities,

whereas Gray was a staunch opponent of that group. Agassiz also felt

each human race had different origins, but Gray believed in the unity of

all humans.

Agassiz's engagement for the Lowell Institute lectures precipitated the establishment, in 1847, of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard University, with Agassiz as its head. Harvard appointed him professor of zoology and geology, and he founded the Museum of Comparative Zoology

there in 1859, serving as the museum's first director until his death

in 1873. During his tenure at Harvard, Agassiz studied the effect of the

last ice age on North America.

Agassiz continued his lectures for the Lowell Institute. In

succeeding years, he gave lectures on "Ichthyology" (1847–48 season),

"Comparative Embryology" (1848–49), "Functions of Life in Lower Animals"

(1850–51), "Natural History" (1853–54), "Methods of Study in Natural

History" (1861–62), "Glaciers and the Ice Period" (1864–65), "Brazil"

(1866–67) and "Deep Sea Dredging" (1869–70). In 1850, he married an American college teacher, Elizabeth Cabot Cary, who later wrote introductory books about natural history and a lengthy biography of her husband after he died.

Agassiz served as a non-resident lecturer at Cornell University while also being on faculty at Harvard. In 1852, he accepted a medical professorship of comparative anatomy at Charlestown, Massachusetts, but he resigned in two years.

From this time, Agassiz's, scientific studies dropped off, but he

became one of the best-known scientists in the world. By 1857, Agassiz

was so well-loved that his friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote "The fiftieth birthday of Agassiz" in his honor, and read it at a dinner given for Agassiz by the Saturday Club in Cambridge. His own writing continued with four (of a planned ten) volumes of Natural History of the United States, published from 1857 to 1862. He also published a catalog of papers in his field, Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae, in four volumes between 1848 and 1854.

Stricken by ill health in the 1860s, Agassiz resolved to return

to the field for relaxation and to resume his studies of Brazilian fish.

In April 1865, he led a party to Brazil. Returning home in August 1866,

an account of this expedition, entitled A Journey in Brazil, was published in 1868. In December 1871 he made a second eight-month excursion, known as the Hassler expedition under the command of Commander Philip Carrigan Johnson (brother of Eastman Johnson), visiting South America on its southern Atlantic and Pacific seaboards. The ship explored the Magellan Strait, which drew the praise of Charles Darwin.

Elizabeth Agassiz wrote, at the Strait: '. ... .the Hassler

pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and

forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers

in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing

down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by

them. ... These were weeks of exquisite delight to Agassiz. The vessel

often skirted the shore so closely that its geology could be studied

from the deck.'

Legacy

Agassiz in middle age

From his first marriage to Cecilie Bruan, Agassiz had two daughters in addition to son Alexander.

In 1863, Agassiz's daughter Ida married Henry Lee Higginson, who later founded the Boston Symphony Orchestra and was a benefactor to Harvard University and other schools.

On November 30, 1860, Agassiz's daughter Pauline was married to Quincy Adams Shaw (1825–1908), a wealthy Boston merchant and later benefactor to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

In the last years of his life, Agassiz worked to establish a

permanent school where zoological science could be pursued amid the

living subjects of its study. In 1873, a private philanthropist (John

Anderson) gave Agassiz the island of Penikese, in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts (south of New Bedford),

and presented him with $50,000 to permanently endow it as a practical

school of natural science, especially devoted to the study of marine

zoology. The John Anderson school collapsed soon after Agassiz's death; it is considered a precursor of the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory, which is nearby.

Agassiz had a profound influence on the American branches of his

two fields, teaching many future scientists that would go on to

prominence, including Alpheus Hyatt, David Starr Jordan, Joel Asaph Allen, Joseph Le Conte, Ernest Ingersoll, William James, Nathaniel Shaler, Samuel Hubbard Scudder, Alpheus Packard, and his son Alexander Emanuel Agassiz, among others. He had a profound impact on paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott and natural scientist Edward S. Morse.

Agassiz had a reputation for being a demanding teacher. He would

allegedly "lock a student up in a room full of turtle-shells, or

lobster-shells, or oyster-shells, without a book or a word to help him,

and not let him out till he had discovered all the truths which the

objects contained."

Two of Agassiz's most prominent students detailed their personal

experiences under his tutelage: Scudder, in a short magazine article for

Every Saturday, and Shaler, in his Autobiography. These and other recollections were collected and published by Lane Cooper in 1917, which Ezra Pound was to draw on for his anecdote of Agassiz and the sunfish.

In the early 1840s, Agassiz named two fossil fish species after Mary Anning —Acrodus anningiae, and Belenostomus anningiae— and another after her friend, Elizabeth Philpot.

Anning was a paleontologist known around the world for important finds,

but, because of her gender, she was often not formally recognized for

her work. Agassiz was grateful for the help the women gave him in

examining fossil fish specimens during his visit to Lyme Regis in 1834.

Agassiz died in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1873 and was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, joined later by his wife. His monument is a boulder from a glacial moraine of the Aar near the site of the old Hôtel des Neuchâtelois, not far from the spot where his hut once stood; his grave is sheltered by pine trees from his old home in Switzerland.

The Cambridge elementary school north of Harvard University was

named in his honor and the surrounding neighborhood became known as "Agassiz" as a result. The school's name was changed to the Maria L. Baldwin School on May 21, 2002, due to concerns about Agassiz's alleged racism, and to honor Maria Louise Baldwin the African-American principal of the school who served from 1889 until 1922. The neighborhood, however, continues to be known as Agassiz. An elementary school called the Agassiz Elementary School in Minneapolis, Minnesota existed from 1922–1981.

Agassiz's

grave, Mt Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a boulder from

the moraine of the Aar Glaciers, near where he once lived.

An ancient glacial lake that formed in the Great Lakes region of North America, Lake Agassiz, is named after him, as are Mount Agassiz in California's Palisades, Mount Agassiz, in the Uinta Mountains, Agassiz Peak in Arizona and in his native Switzerland, the Agassizhorn in the Bernese Alps. Agassiz Glacier (Montana) and Agassiz Creek in Glacier National Park and Agassiz Glacier (Alaska) in Saint Elias Mountains, Mount Agassiz in Bethlehem, New Hampshire in the White Mountains also bear his name. A crater on Mars Crater Agassiz and a promontorium on the Moon are also named in his honour. A headland situated in Palmer Land, Antarctica is named in his honor, Cape Agassiz. A main-belt asteroid named 2267 Agassiz is also named in association with Louis Agassiz.

Several animal species are named in honor of Louis Agassiz, including Apistogramma agassizii Steindachner, 1875 (Agassiz's dwarf cichlid); Isocapnia agassizi Ricker, 1943 (a stonefly); Publius agassizi (Kaup, 1871) (a passalid beetle); Xylocrius agassizi (LeConte, 1861) (a longhorn beetle); Exoprosopa agassizi Loew, 1869 (a bee fly); Chelonia agassizii Bocourt, 1868 (Galápagos green turtle); Philodryas agassizii (Jan, 1863) (a South American snake); and the most well-known, Gopherus agassizii (Cooper, 1863) (the desert tortoise).

In 2005 the EGU

Division on Cryospheric Sciences established the Louis Agassiz Medal,

awarded to individuals in recognition of their outstanding scientific

contribution to the study of the cryosphere on Earth or elsewhere in the solar system.

Agassiz took part in a monthly gathering called the Saturday Club at the Parker House, a meeting of Boston writers and intellectuals. He was therefore mentioned in a stanza of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. poem "At the Saturday Club":

There, at the table's further end I see

In his old place our Poet's vis-à-vis,

The great PROFESSOR, strong, broad-shouldered, square,

In life's rich noontide, joyous, debonair

...

How will her realm be darkened, losing thee,

Her darling, whom we call our AGASSIZ!

Polygenism

After Agassiz came to the United States, he wrote prolifically on polygenism,

which holds that animals, plants and humans were all created in

"special provinces" with distinct populations of species created in and

for each province, and that these populations were endowed with unequal

attributes. Agassiz denied that migration and adaptation

could account for the geographical age or any of the past. Adaptation

takes time; in an example, Agassiz questioned how plants or animals

could migrate through regions they were not equipped to handle.

According to Agassiz the conditions in which particular creatures live

"are the conditions necessary to their maintenance, and what among

organized beings is essential to their temporal existence must be at

least one of the conditions under which they were created". Agassiz was opposed to monogenism and evolution, believing that the theory of evolution reduced the wisdom of God to an impersonal materialism.

Agassiz was influenced by philosophical idealism and the scientific work of Georges Cuvier. Agassiz believed there is one species of humans but many different creations of races. These ideas are now included under the rubric of scientific racism.

According to Agassiz, genera and species were ideas in the mind of God;

their existence in God's mind prior to their physical creation meant

that God could create humans as one species yet in several distinct and

geographically separate acts of creation. Agassiz was in modern terms a creationist

who believed nature had order because God created it directly. Agassiz

viewed his career in science as a search for ideas in the mind of the

creator expressed in creation.

After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, toppled Agassiz's statue from the façade of Stanford's zoology building, Stanford President David Starr Jordan wrote that "Somebody—Dr. Angell, perhaps—remarked that 'Agassiz was great in the abstract but not in the concrete.'"

Agassiz, like other polygenists, believed the Book of Genesis

recounted the origin of the white race only and that the animals and

plants in the Bible refer only to those species proximate and familiar

to Adam and Eve. Agassiz believed that the writers of the Bible only knew of regional events, for example Noah's flood was a local event only known to the regions near those that were populated by ancient Hebrews.

Stephen Jay Gould

asserted that Agassiz's observations sprang from racist bias, in

particular from his revulsion on first encountering African-Americans in

the United States.

However, others have asserted that, despite favoring polygenism,

Agassiz rejected racism and believed in a spiritualized human unity.

Agassiz believed God made all men equal, and that intellectualism and

morality, as developed in civilization, make men equal before God. Agassiz never supported slavery, and claimed his views on polygenism had nothing to do with politics.

Accusations of racism against Agassiz have prompted the renaming

of landmarks, schoolhouses, and other institutions (which abound in

Massachusetts) that bear his name. Opinions on these events are often mixed, given his extensive scientific legacy in other areas. In 2007, the Swiss government acknowledged the "racist thinking" of Agassiz but declined to rename the Agassizhorn summit. In 2017, the Swiss Alpine Club

declined to revoke Agassiz's status as a member of honor, which he

received in 1865 for his scientific work, because the club considered

this status to have lapsed on Agassiz's death. Civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump representing descendant Tamara Lanier filed a lawsuit against Harvard University over ownership of images of Renty and his daughter Delia collected by Agassiz in support of his theories.

Works

- Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (1833–1843)

- History of the Freshwater Fishes of Central Europe (1839–1842)

- Études sur les glaciers (1840)

- Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (1840–1845)

- Nomenclator Zoologicus (1842–1846)

- Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Gres Rouge, ou Systeme Devonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (1844–1845)

- Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae (1848)

- (with A. A. Gould) Principles of Zoology for the use of Schools and Colleges (Boston, 1848)

- Lake Superior: Its Physical Character, Vegetation and Animals, compared with those of other and similar regions (Boston: Gould, Kendall and Lincoln, 1850)

- Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1857–1862)

- Geological Sketches (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866)

- A Journey in Brazil (1868)

- De l'espèce et de la classification en zoologie [Essay on classification] (Trans. Felix Vogeli. Paris: Bailière, 1869)

- Geological Sketches (Second Series) (Boston: J.R. Osgood, 1876)

- Essay on Classification, by Louis Agassiz (1962, Cambridge)