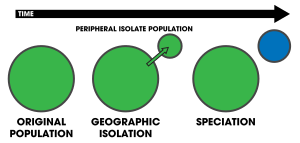

Diagrams

representing the process of peripatric and centrifugal speciation. In

peripatry, a small population becomes isolated on the periphery of the

central population evolving reproductive isolation (blue) due to reduced

gene flow. In centrifugal speciation, an original population (green)

range expands and contracts, leaving an isolated fragment population

behind. The central population (changed to blue) evolves reproductive

isolation in contrast to peripatry.

The concept of peripatric speciation was first outlined by the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr in 1954. Since then, other alternative models have been developed such as centrifugal speciation, that posits that a species' population experiences periods of geographic range expansion followed by shrinking periods, leaving behind small isolated populations on the periphery of the main population. Other models have involved the effects of sexual selection on limited population sizes. Other related models of peripherally isolated populations based on chromosomal rearrangements have been developed such as budding speciation and quantum speciation.

The existence of peripatric speciation is supported by observational evidence and laboratory experiments. Scientists observing the patterns of a species biogeographic distribution and its phylogenetic relationships are able to reconstruct the historical process by which they diverged. Further, oceanic islands are often the subject of peripatric speciation research due to their isolated habitats—with the Hawaiian Islands widely represented in much of the scientific literature.

History

Peripatric speciation was originally proposed by Ernst Mayr in 1954, and fully theoretically modeled in 1982. It is related to the founder effect, where small living populations may undergo selection bottlenecks. The founder effect is based on models that suggest peripatric speciation can occur by the interaction of selection and genetic drift, which may play a significant role. Mayr first conceived of the idea by his observations of kingfisher populations in New Guinea and its surrounding islands. Tanysiptera galatea

was largely uniform in morphology on the mainland, but the populations

on the surrounding islands differed significantly—referring to this

pattern as "peripatric". This same pattern was observed by many of Mayr's contemporaries at the time such as by E. B. Ford's studies of Maniola jurtina. Around the same time, the botanist Verne Grant developed a model of quantum speciation very similar to Mayr's model in the context of plants.

In what has been called Mayr's genetic revolutions, he postulated

that genetic drift played the primary role that resulted in this

pattern. Seeing that a species cohesion is maintained by conservative forces such as epistasis and the slow pace of the spread of favorable alleles in a large population (based heavily on J. B. S. Haldane's calculations), he reasoned that speciation could only take place in which a population bottleneck occurred.

A small, isolated, founder population could be established on an island

for example. Containing less genetic variation from the main

population, shifts in allele frequencies may occur from different

selection pressures.

This to further changes in the network of linked loci, driving a

cascade of genetic change, or a "genetic revolution"—a large-scale

reorganization of the entire genome of the peripheral population.

Mayr did recognize that the chances of success were incredibly low and

that extinction was likely; though noting that some examples of

successful founder populations existed at the time.

Shortly after Mayr, William Louis Brown, Jr. proposed an

alternative model of peripatric speciation in 1957 called centrifugal

speciation. In 1976 and 1980, the Kaneshiro model of peripatric

speciation was developed by Kenneth Y. Kaneshiro which focused on sexual selection as a driver for speciation during population bottlenecks.

Models

Peripatric

Peripatric speciation models are identical to models of vicariance (allopatric speciation). Requiring both geographic separation and time, speciation can result as a predictable byproduct. Peripatry can be distinguished from allopatric speciation by three key features:

- The size of the isolated population

- Strong selection caused by the dispersal and colonization of novel environments,

- The effects of genetic drift on small populations.

The size of a population is important because individuals colonizing a

new habitat likely contain only a small sample of the genetic variation

of the original population. This promotes divergence due to strong

selective pressures, leading to the rapid fixation of an allele within the descendant population. This gives rise to the potential for genetic incompatibilities to evolve. These incompatibilities cause reproductive isolation, giving rise to—sometimes rapid—speciation events.

Furthermore, two important predictions are invoked, namely that

geological or climactic changes cause populations to become locally

fragmented (or regionally when considering allopatric speciation), and

that an isolated population's reproductive traits evolve enough as to

prevent interbreeding upon potential secondary contact.

The peripatric model results in, what have been called,

progenitor-derivative species pairs, whereby the derivative species (the

peripherally isolated population)—geographically and genetically

isolated from the progenitor species—diverges. A specific phylogenetic signature results from this mode of speciation: the geographically widespread progenitor species becomes paraphyletic (thereby becoming a paraspecies), with respect to the derivative species (the peripheral isolate). The concept of a paraspecies is therefore a logical consequence of the evolutionary species concept, by which one species gives rise to a daughter species. It is thought that the character traits of the peripherally isolated species become apomorphic, while the central population remains pleisomorphic.

Modern cladistic methods have developed definitions that have

incidentally removed derivative species by defining clades in a way that

assumes that when a speciation event occurs, the original species no

longer exists, while two new species arise; this is not the case in

peripatric speciation. Mayr warned against this, as it causes a species to lose their classification status. Loren H. Rieseberg and Luc Brouillet recognized the same dilemma in plant classification.

Quantum and budding speciation

The botanist Verne Grant proposed the term quantum speciation that combined the ideas of J. T. Gulick (his observation of the variation of species in semi-isolation), Sewall Wright (his models of genetic drift), Mayr (both his peripatric and genetic revolution models), and George Gaylord Simpson (his development of the idea of quantum evolution).

Quantum speciation is a rapid process with large genotypic or

phenotypic effects, whereby a new, cross-fertilizing plant species buds

off from a larger population as a semi-isolated peripheral population.

Interbreeding and genetic drift takes place due to the reduced

population size, driving changes to the genome that would most likely

result in extinction (due to low adaptive value). In rare instances, chromosomal traits with adaptive value may arise, resulting in the origin of a new, derivative species. Evidence for the occurrence of this type of speciation has been found in several plant species pairs: Layia discoidea and L. glandulosa, Clarkia lingulata and C. biloba, and Stephanomeria malheurensis and S. exigua ssp. coronaria.

A closely related model of peripatric speciation is called

budding speciation—largely applied in the context of plant speciation. The budding process, where a new species originates at the margins of an ancestral range, is thought to be common in plants—especially in progenitor-derivative species pairs.

Centrifugal speciation

William

Louis Brown, Jr. proposed an alternative model of peripatric speciation

in 1957 called centrifugal speciation. This model contrasts with

peripatric speciation by virtue of the origin of the genetic novelty

that leads to reproductive isolation.

A population of a species experiences periods of geographic range

expansion followed by periods of contraction. During the contraction

phase, fragments of the population become isolated as small refugial

populations on the periphery of the central population. Because of the

large size and potentially greater genetic variation within the central

population, mutations

arise more readily. These mutations are left in the isolated peripheral

populations, whereby, promoting reproductive isolation. Consequently,

Brown suggested that during another expansion phase, the central

population would overwhelm the peripheral populations, hindering

speciation. However, if the species finds a specialized ecological

niche, the two may coexist. The phylogenetic signature of this model is that the central population becomes derived, while the peripheral isolates stay pleisomorphic—the

reverse of the general model. In contrast to centrifugal speciation,

peripatric speciation has sometimes been referred to as centripetal speciation (see figures 1 and 2 for a contrast).

Centrifugal speciation has been largely ignored in the scientific

literature, often dominated by the traditional model of peripatric

speciation. Despite this, Brown cited a wealth of evidence to support his model, of which has not yet been refuted.

Peromyscus polionotus and P. melanotis (the peripherally isolated species from the central population of P. maniculatus) arose via the centrifugal speciation model. Centrifugal speciation may have taken place in tree kangaroos, South American frogs (Ceratophrys), shrews (Crocidura), and primates (Presbytis melalophos). John C. Briggs associates centrifugal speciation with centers of origin,

contending that the centrifugal model is better supported by the data,

citing species patterns from the proposed 'center of origin' within the Indo-West Pacific.

Kaneshiro model

In

the Kaneshiro model, a sample of a larger population results in an

isolated population with less males containing attractive traits. Over

time, choosy females are selected against as the population increases. Sexual selection drives new traits to arise (green), reproductively isolating the new population from the old one (blue).

When a sexual species experiences a population bottleneck—that is, when the genetic variation is reduced due to small population size—mating discrimination among females may be altered by the decrease in courtship behaviors of males.

Sexual selection pressures may become weakened by this in an isolated

peripheral population, and as a by-product of the altered mating

recognition system, secondary sexual traits may appear. Eventually, a growth in population size paired with novel female mate preferences will give rise to reproductive isolation from the main population-thereby completing the peripatric speciation process.

Support for this model comes from experiments and observation of

species that exhibit asymmetric mating patterns such as the Hawaiian Drosophila species or the Hawaiian cricket Laupala.

However, this model has not been entirely supported by experiments, and

therefore, it may not represent a plausible process of peripatric

speciation that takes place in nature.

Evidence

Observational evidence and laboratory experiments support the occurrence of peripatric speciation. Islands and archipelagos

are often the subject of speciation studies in that they represent

isolated populations of organisms. Island species provide direct

evidence of speciation occurring peripatrically in such that, "the

presence of endemic species on oceanic islands whose closest relatives inhabit a nearby continent" must have originated by a colonization event. Comparative phylogeography of oceanic archipelagos shows consistent patterns of sequential colonization and speciation along island chains, most notably on the Azores islands, Canary Islands, Society Islands, Marquesas Islands, Galápagos Islands, Austral Islands, and the Hawaiian Islands—all of which express geological patterns of spatial isolation and, in some cases, linear arrangement. Peripatric speciation also occurs on continents, as isolation of small populations can occur through various geographic and dispersion events. Laboratory studies have been conducted where populations of Drosophila, for example, are separated from one another and evolve in reproductive isolation.

Hawaiian archipelago

Colonization events of species from the genus Cyanea (green) and species from the genus Drosophila (blue) on the Hawaiian island chain. Islands age from left to right, (Kauai being the oldest and Hawaii

being the youngest). Speciation arises peripatrically as they

spatiotemporally colonize new islands along the chain. Lighter blue and

green indicate colonization in the reverse direction from young-to-old.

A map of the Hawaiian archipelago showing the colonization routes of Theridion grallator

superimposed. Purple lines indicate colonization occurring in

conjunction with island age where light purple indicates backwards

colonization. T. grallator is not present on Kauai or Niihau so colonization may have occurred from there, or the nearest continent.

The sequential colonization and speciation of the ‘Elepaio subspecies along the Hawaiian island chain.

Drosophila species on the Hawaiian archipelago have helped researchers understand speciation processes in great detail. It is well established that Drosophila has undergone an adaptive radiation into hundreds of endemic species on the Hawaiian island chain; originating from a single common ancestor (supported from molecular analysis). Studies consistently find that colonization of each island occurred from older to younger islands, and in Drosophila, speciating peripatrically at least fifty percent of the time. In conjunction with Drosophila, Hawaiian lobeliads (Cyanea) have also undergone an adaptive radiation, with upwards of twenty-seven percent of extant

species arising after new island colonization—exemplifying peripatric

speciation—once again, occurring in the old-to-young island direction.

Other endemic species in Hawaii also provide evidence of peripatric speciation such as the endemic flightless crickets (Laupala). It has been estimated that, "17 species out of 36 well-studied cases of [Laupala] speciation were peripatric". Plant species in genera's such as Dubautia, Wilkesia, and Argyroxiphium have also radiated along the archipelago. Other animals besides insects show this same pattern such as the Hawaiian amber snail (Succinea caduca), and ‘Elepaio flycatchers.

Tetragnatha spiders have also speciated peripatrically on the Hawaiian islands,

Numerous arthropods have been documented existing in patterns

consistent with the geologic evolution of the island chain, in such

that, phylogenetic reconstructions find younger species inhabiting the

geologically younger islands and older species inhabiting the older

islands

(or in some cases, ancestors date back to when islands currently below

sea level were exposed). Spiders such as those from the genus Orsonwelles exhibit patterns compatible with the old-to-young geology. Other endemic genera such as Argyrodes have been shown to have speciated along the island chain. Pagiopalus, Pedinopistha, and part of the family Thomisidae have adaptively radiated along the island chain, as well as the wolf spider family, Lycosidae.

A host of other Hawaiian endemic arthropod species and genera

have had their speciation and phylogeographical patterns studied: the Drosophila grimshawi species complex, damselflies (Megalagrion xanthomelas and Megalagrion pacificum), Doryonychus raptor, Littorophiloscia hawaiiensis, Anax strenuus, Nesogonia blackburni, Theridion grallator, Vanessa tameamea, Hyalopeplus pellucidus, Coleotichus blackburniae, Labula, Hawaiioscia, Banza (in the family Tettigoniidae), Caconemobius, Eupethicea, Ptycta, Megalagrion, Prognathogryllus, Nesosydne, Cephalops, Trupanea, and the tribe Platynini—all suggesting repeated radiations among the islands.

Other islands

Phylogenetic studies of a species of crab spider (Misumenops rapaensis) in the genus Thomisidae located on the Austral Islands have established the, "sequential colonization of [the] lineage down the Austral archipelago toward younger islands". M. rapaensis

has been traditionally thought of as a single species; whereas this

particular study found distinct genetic differences corresponding to the

sequential age of the islands. The figwart plant species Scrophularia lowei is thought to have arisen through a peripatric speciation event, with the more widespread mainland species, Scrophularia arguta dispersing to the Macaronesian islands. Other members of the same genus have also arisen by single colonization events between the islands.

Species patterns on continents

Satellite image of the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park (outlined in green) in Bolivia, South America. The white arrow indicates the location of the isolated forest fragment.

The occurrence of peripatry on continents is more difficult to detect

due to the possibility of vicariant explanations being equally likely. However, studies concerning the Californian plant species Clarkia biloba and C. lingulata strongly suggest a peripatric origin. In addition, a great deal of research has been conducted on several species of land snails involving chirality that suggests peripatry (with some authors noting other possible interpretations).

The chestnut-tailed antbird (Sciaphylax hemimelaena) is located within the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park

(Serrania de Huanchaca) in Bolivia. Within this region exists a forest

fragment estimated to have been isolated for 1000–3000 years. The

population of S. hemimelaena antbirds that reside in the isolated

patch express significant song divergence; thought to be an "early

step" in the process of peripatric speciation. Further, peripheral

isolation "may partly explain the dramatic diversification of suboscines in Amazonia".

The montane spiny throated reed frog species complex (genus: Hyperolius)

originated through occurrences of peripatric speciation events. Lucinda

P. Lawson maintains that the species' geographic ranges within the

Eastern Afromontane

Biodiversity Hotspot support a peripatric model that is driving

speciation; suggesting that this mode of speciation may play a

significant role in "highly fragmented ecosystems".

In a study of the phylogeny and biogeography of the land snail genus Monacha, the species M. ciscaucasica is thought to have speciated peripatrically from a population of M. roseni. In addition, M. claussi consists of a small population located on the peripheral of the much larger range of M. subcarthusiana suggesting that it also arose by peripatric speciation.

Red spruce (Picea rubens) has arisen from an isolated population of black spruce (Picea mariana). During the Pleistocene, a population of black spruce became geographically isolated, likely due to glaciation.

The geographic range of the black spruce is much larger than the red

spruce. The red spruce has significantly lower genetic diversity in both

its DNA and its mitochondrial DNA than the black spruce. Furthermore, the genetic variation of the red spruce has no unique mitochondrial haplotypes,

only subsets of those in the black spruce; suggesting that the red

spruce speciated peripatrically from the black spruce population. It is thought that the entire genus Picea

in North America has diversified by the process of peripatric

speciation, as numerous pairs of closely related species in the genus

have smaller southern population ranges; and those with overlapping

ranges often exhibit weak reproductive isolation.

Using a phylogeographic approach paired with ecological niche models (i.e. prediction and identification of expansion and contraction species ranges into suitable habitats based on current ecological niches, correlated with fossil and molecular data), researchers found that the prairie dog species Cynomys mexicanus speciated peripatrically from Cynomys ludovicianus

approximately 230,000 years ago. North American glacial cycles promoted

range expansion and contraction of the prairie dogs, leading to the

isolation of a relic population in a refugium located in the present day Coahuila, Mexico. This distribution and paleobiogeographic pattern correlates with other species expressing similar biographic range patterns such as with the Sorex cinereus complex.

Laboratory experiments

| Species | Replicates | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Drosophila adiastola | 1 | 1979 |

| Drosophila silvestris | 1 | 1980 |

| Drosophila pseudoobscura | 8 | 1985 |

| Drosophila simulans | 8 | 1985 |

| Musca domestica | 6 | 1991 |

| Drosophila pseudoobscura | 42 | 1993 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | 50 | 1998 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | 19; 19 | 1999 |

| Drosophila grimshawi | 1 | N/A |

Peripatric speciation has been researched in both laboratory studies and nature. Jerry Coyne and H. Allen Orr in Speciation

suggest that most laboratory studies of allopatric speciation are also

examples of peripatric speciation due to their small population sizes

and the inevitable divergent selection that they undergo. Much of the laboratory research concerning peripatry is inextricably linked to founder effect research. Coyne and Orr conclude that selection's role in speciation is well established, whereas genetic drift's role is unsupported by experimental and field data—suggesting that founder-effect speciation does not occur. Nevertheless, a great deal of research has been conducted on the matter, and one study conducted involving bottleneck populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura found evidence of isolation after a single bottleneck.

The table is a non-exhaustive table of laboratory experiments

focused explicitly on peripatric speciation. Most of the studies also

conducted experiments on vicariant speciation as well. The "replicates"

column signifies the number of lines used in the experiment—that is, how

many independent populations were used (not the population size or the

number of generations performed).