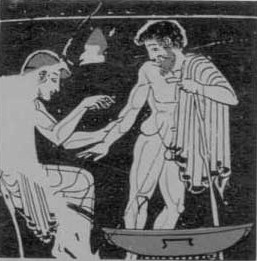

Ancient Greek painting on a vase, showing a physician (iatros) bleeding a patient

Today, the term phlebotomy refers to the drawing of blood for laboratory analysis or blood transfusion. Therapeutic phlebotomy refers to the drawing of a unit of blood in specific cases like hemochromatosis, polycythemia vera, porphyria cutanea tarda, etc., to reduce the number of red blood cells. The traditional medical practice of bloodletting is today considered to be a pseudoscience.

In the ancient world

A chart showing the parts of the body to be bled for different diseases, c. 1310–1320

Points for blood-letting, Hans von Gersdorff (surgeon), Field book of wound medicine, 1517

Passages from the Ebers Papyrus may indicate that bloodletting by scarification was an accepted practice in Ancient Egypt.

Egyptian burials have been reported to contain bloodletting instruments.

According to some accounts, the Egyptians based the idea on their observations of the Hippopotamus, confusing its red sweat with blood, and believing that it scratched itself to relieve distress.

In Greece, bloodletting was in use in the fifth century BC during the lifetime of Hippocrates, who mentions this practice but generally relied on dietary techniques. Erasistratus,

however, theorized that many diseases were caused by plethoras, or

overabundances, in the blood and advised that these plethoras be

treated, initially, by exercise, sweating, reduced food intake, and vomiting. Herophilus advocated bloodletting. Archagathus, one of the first Greek physicians to practice in Rome, also believed in the value of bloodletting.

"Bleeding" a patient to health was modeled on the process of

menstruation. Hippocrates believed that menstruation functioned to

"purge women of bad humours". During the Roman Empire, the Greek physician Galen, who subscribed to the teachings of Hippocrates, advocated physician-initiated bloodletting.

The popularity of bloodletting in the classical Mediterranean

world was reinforced by the ideas of Galen, after he discovered that not

only veins but also arteries were filled with blood, not air as was commonly believed at the time. There were two key concepts in his system of bloodletting. The first was that blood was created and then used up; it did not circulate, and so it could "stagnate" in the extremities. The second was that humoral

balance was the basis of illness or health, the four humours being

blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile, relating to the four Greek classical elements

of air, water, earth, and fire respectively. Galen believed that blood

was the dominant humour and the one in most need of control. In order to

balance the humours, a physician would either remove "excess" blood

(plethora) from the patient or give them an emetic to induce vomiting, or a diuretic to induce urination.

Galen created a complex system of how much blood should be

removed based on the patient's age, constitution, the season, the

weather and the place. "Do-it-yourself" bleeding instructions following

these systems were developed. Symptoms of plethora were believed to include fever, apoplexy, and headache. The blood to be let was of a specific nature determined by the disease: either arterial or venous, and distant or close to the area of the body affected. He linked different blood vessels with different organs, according to their supposed drainage. For example, the vein in the right hand would be let for liver problems and the vein in the left hand for problems with the spleen. The more severe the disease, the more blood would be let. Fevers required copious amounts of bloodletting.

Middle Ages

The Talmud

recommended a specific day of the week and days of the month for

bloodletting, and similar rules, though less codified, can be found

among Christian writings advising which saints' days

were favourable for bloodletting. During medieval times bleeding charts

were common, showing specific bleeding sites on the body in alignment

with the planets and zodiacs. Islamic medical authors too advised bloodletting, particularly for fevers. It was practised according to seasons and certain phases of the moon in the lunar calendar. The practice was probably passed by the Greeks with the translation of ancient texts to Arabic and is different than bloodletting by cupping mentioned in the traditions of Muhammad. When Muslim theories became known in the Latin-speaking countries of Europe, bloodletting became more widespread. Together with cautery, it was central to Arabic surgery; the key texts Kitab al-Qanun and especially Al-Tasrif li-man 'ajaza 'an al-ta'lif both recommended it. It was also known in Ayurvedic medicine, described in the Susruta Samhita.

Use through the 19th century

Ioannis Sculteti, Armamentium Chirugiae, 1693 – Diagrammed transfusion of sheep's blood

Bloodletting-Set of a Barber Surgeon, beginning of the 19th century, Märkisches Museum Berlin

Even after the humoral system fell into disuse, the practice was continued by surgeons and barber-surgeons. Though the bloodletting was often recommended by physicians, it was carried out by barbers. This led to the distinction between physicians and surgeons. The red-and-white-striped pole of the barbershop,

still in use today, is derived from this practice: the red symbolizes

blood while the white symbolizes the bandages. Bloodletting was used to

"treat" a wide range of diseases, becoming a standard treatment for

almost every ailment, and was practiced prophylactically as well as therapeutically.

Scarificator

Scarificator mechanism

Scarificator, showing depth adjustment bar

Diagram of scarificator, showing depth adjustment

A number of different methods were employed. The most common was phlebotomy, or venesection

(often called "breathing a vein"), in which blood was drawn from one or

more of the larger external veins, such as those in the forearm or

neck. In arteriotomy, an artery was punctured, although generally only in the temples. In scarification (not to be confused with scarification, a method of body modification), the "superficial" vessels were attacked, often using a syringe, a spring-loaded lancet, or a glass cup that contained heated air, producing a vacuum within (see fire cupping). There was also a specific bloodletting tool called a scarificator,

used primarily in 19th century medicine. It has a spring-loaded

mechanism with gears that snaps the blades out through slits in the

front cover and back in, in a circular motion. The case is cast brass,

and the mechanism and blades steel. One knife bar gear has slipped

teeth, turning the blades in a different direction than those on the

other bars. The last photo and the diagram show the depth adjustment bar

at the back and sides.

Bloodletting in 1860, one of only three known photographs of the procedure.

Photograph of a Bloodletting in 1922

Leeches could also be used. The withdrawal of so much blood as to induce syncope (fainting) was considered beneficial, and many sessions would only end when the patient began to swoon.

William Harvey disproved the basis of the practice in 1628, and the introduction of scientific medicine, la méthode numérique, allowed Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis to demonstrate that phlebotomy was entirely ineffective in the treatment of pneumonia and various fevers in the 1830s. Nevertheless, in 1838, a lecturer at the Royal College of Physicians

would still state that "blood-letting is a remedy which, when

judiciously employed, it is hardly possible to estimate too highly", and Louis was dogged by the sanguinary Broussais,

who could recommend leeches fifty at a time. Some physicians resisted

Louis' work because they "were not prepared to discard therapies

'validated by both tradition and their own experience on account of somebody else's numbers'."

Bloodletting was used to treat almost every disease. One British

medical text recommended bloodletting for acne, asthma, cancer, cholera,

coma, convulsions, diabetes, epilepsy, gangrene, gout, herpes,

indigestion, insanity, jaundice, leprosy, ophthalmia, plague, pneumonia,

scurvy, smallpox, stroke, tetanus, tuberculosis, and for some one

hundred other diseases. Bloodletting was even used to treat most forms

of hemorrhaging such as nosebleed, excessive menstruation, or

hemorrhoidal bleeding. Before surgery or at the onset of childbirth,

blood was removed to prevent inflammation. Before amputation, it was

customary to remove a quantity of blood equal to the amount believed to

circulate in the limb that was to be removed.

There were also theories that bloodletting would cure "heartsickness" and "heartbreak". A French physician, Jacques Ferrand

wrote a book in 1623 on the uses of bloodletting to cure a broken

heart. He recommended bloodletting to the point of heart failure

(literal).

Leeches became especially popular in the early nineteenth

century. In the 1830s, the French imported about forty million leeches a

year for medical purposes, and in the next decade, England imported six

million leeches a year from France alone. Through the early decades of

the century, hundreds of millions of leeches were used by physicians

throughout Europe.

Bloodletting was also popular in the young United States of America, where Benjamin Rush (a signatory of the Declaration of Independence) saw the state of the arteries as the key to disease, recommending levels of bloodletting that were high even for the time. George Washington

asked to be bled heavily after he developed a throat infection from

weather exposure. Within a ten-hour period, a total of 124–126 ounces (3.75 liters) of blood was withdrawn prior to his death from a throat infection in 1799.

Bloodsticks for use when bleeding animals

One reason for the continued popularity of bloodletting (and purging) was that, while anatomical

knowledge, surgical and diagnostic skills increased tremendously in

Europe from the 17th century, the key to curing disease remained

elusive, and the underlying belief was that it was better to give any

treatment than nothing at all. The psychological benefit of bloodletting

to the patient (a placebo effect)

may sometimes have outweighed the physiological problems it caused.

Bloodletting slowly lost favour during the 19th century, after French

physician Dr. Pierre Louis conducted an experiment in which he studied

the effect of bloodletting on pneumonia patients. A number of other ineffective or harmful treatments were available as placebos—mesmerism,

various processes involving the new technology of electricity, many

potions, tonics, and elixirs. Yet, bloodletting persisted during the

19th century partly because it was readily available to people of any

socioeconomic status.

Possible validity

In the absence of other treatments, bloodletting actually is beneficial in some circumstances, including hemochromatosis, the fluid overload of heart failure, and possibly simply to reduce blood pressure.

In other cases, such as those involving agitation, the reduction in

blood pressure might appear beneficial due to the sedative effects. In

1844, Joseph Pancoast listed the advantages of bloodletting in "A Treatise on Operative Surgery". Not all of these reasons are outrageous nowadays:

The opening of the superficial vessels for the purpose of extracting blood constitutes one of the most common operations of the practitioner. The principal results, which we effect by it, are 1st. The diminution of the mass of the blood, by which the overloaded capillary or larger vessels of some affected part may be relieved; 2. The modification of the force and frequency of the heart's action; 3. A change in the composition of the blood, rendering it less stimulating; the proportion of serum becoming increased after bleeding, in consequence of its being reproduced with greater facility than the other elements of the blood; 4. The production of syncope, for the purpose of effecting a sudden general relaxation of the system; and, 5. The derivation, or drawing as it is alleged, of the force of the circulation from some of the internal organs, towards the open outlet of the superficial vessel. These indications may be fulfilled by opening either a vein or an artery.

Controversy and use into the 20th century

Bloodletting

gradually declined in popularity over the course of the 19th century,

becoming rather uncommon in most places, before its validity was

thoroughly debated. In the medical community of Edinburgh,

bloodletting was abandoned in practice before it was challenged in

theory, a contradiction highlighted by physician-physiologist John Hughes Bennett. Authorities such as Austin Flint I, Hiram Corson, and William Osler

became prominent supporters of bloodletting in the 1880s and onwards,

disputing Bennett's premise that bloodletting had fallen into disuse

because it didn't work. These advocates framed bloodletting as an

orthodox medical practice, to be used in spite of its general

unpopularity.

Some physicians considered bloodletting useful for a more limited range

of purposes, such as to "clear out" infected or weakened blood or its

ability to "cause hæmorrhages to cease"—as evidenced in a call for a "fair trial for blood-letting as a remedy" in 1871.

Some researchers used statistical methods for evaluating treatment effectiveness to discourage bloodletting. But at the same time, publications by Philip Pye-Smith and others defended bloodletting on scientific grounds.

Bloodletting persisted into the 20th century and was recommended in the 1923 edition of the textbook The Principles and Practice of Medicine. The textbook was originally written by Sir William Osler and continued to be published in new editions under new authors following Osler's death in 1919.

Phlebotomy

Today it is well established that bloodletting is not effective for

most diseases. Indeed, it is mostly harmful, since it can weaken the

patient and facilitate infections. Bloodletting is used today in the

treatment of a few diseases, including hemochromatosis and polycythemia;

however, these rare diseases were unknown and undiagnosable before the

advent of scientific medicine. It is practiced by specifically trained

practitioners in hospitals, using modern techniques.

In most cases, phlebotomy now refers to the removal of small quantities of blood for diagnostic purposes. However, in the case of hemochromatosis, which is now recognized as the most common hereditary disorder in European populations, bloodletting (venesection) has become the mainstay treatment option. In the U.S., according to an academic article posted in the Journal of Infusion Nursing

with data published in 2010, the primary use of phlebotomy was to take

blood that would one day be reinfused back into a person.

In alternative medicine

Though

bloodletting as a general health measure has been shown to be harmful,

it is still commonly indicated for a wide variety of conditions in the Ayurvedic, Unani, and traditional Chinese systems of alternative medicine. Unani is based on a form of humorism, and so in that system, bloodletting is used to correct supposed humoral imbalance.