Norwegian settlers in North Dakota, 1898

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by

which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the

public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than 160 million acres (650 thousand km2;

250 thousand sq mi) of public land, or nearly 10 percent of the total

area of the United States, was given away free to 1.6 million

homesteaders; most of the homesteads were west of the Mississippi River.

An extension of the homestead principle in law, the Homestead Acts were an expression of the Free Soil

policy of Northerners who wanted individual farmers to own and operate

their own farms, as opposed to Southern slave-owners who wanted to buy

up large tracts of land and use slave labor, thereby shutting out free

white farmers.

The first of the acts, the Homestead Act of 1862, opened up

millions of acres. Any adult who had never taken up arms against the Federal government of the United States

could apply. Women and immigrants who had applied for citizenship were

eligible. The 1866 Act explicitly included black Americans and

encouraged them to participate, but rampant discrimination, systemic

barriers and bureaucratic inertia slowed black gains. Historian Michael

Lanza argues that while the 1866 law pack was not as beneficial as it

might have been, it was part of the reason that by 1900 one fourth of

all Southern black farmers owned their own farms.

Several additional laws were enacted in the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Southern Homestead Act of 1866 sought to address land ownership inequalities in the south during Reconstruction. The Timber Culture Act

of 1873 granted land to a claimant who was required to plant trees—the

tract could be added to an existing homestead claim and had no residency

requirement.

The Kinkaid Amendment

of 1904 granted a full section—640 acres (260 ha)–to new homesteaders

settling in western Nebraska. An amendment to the Homestead Act of 1862,

the Enlarged Homestead Act, was passed in 1909 and doubled the allotted

acreage from 160 to 320 acres (65 to 129 ha). Another amended act, the

national Stock-Raising Homestead Act, was passed in 1916 and again

increased the land involved, this time to 640 acres (260 ha).

Background

Land-grant laws similar to the Homestead Acts had been proposed by northern Republicans before the Civil War, but had been repeatedly blocked in Congress by southern Democrats who wanted western lands open for purchase by slave-owners. The Homestead Act of 1860 did pass in Congress, but it was vetoed by President James Buchanan,

a Democrat. After the Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861

(and their representatives had left Congress), the bill passed and was

signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln (May 20, 1862). Daniel Freeman became the first person to file a claim under the new act.

Between 1862 and 1934, the federal government granted 1.6 million

homesteads and distributed 270,000,000 acres (420,000 sq mi) of federal

land for private ownership. This was a total of 10% of all land in the

United States.

Homesteading was discontinued in 1976, except in Alaska, where it

continued until 1986. About 40% of the applicants who started the

process were able to complete it and obtain title to their homesteaded

land after paying a small fee in cash.

History

Donation Land Claim Act of 1850

The Donation Land Claim Act allowed settlers to claim land in the Oregon Territory,

then including the modern states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho and parts

of Wyoming. Settlers were able to claim 320 or 640 acres of land for

free between 1850 and 1854, and then at a cost of $1.25 per acre until

the law expired in 1855.

Homestead Act of 1862

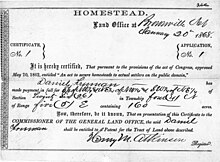

Certificate of homestead in Nebraska given under the Homestead Act, 1862

The "yeoman farmer" ideal of Jeffersonian democracy

was still a powerful influence in American politics during the

1840–1850s, with many politicians believing a homestead act would help

increase the number of "virtuous yeomen". The Free Soil Party of

1848–52, and the new Republican Party after 1854, demanded that the new

lands opening up in the west be made available to independent farmers,

rather than wealthy planters who would develop it with the use of slaves

forcing the yeomen farmers onto marginal lands.

Southern Democrats had continually fought (and defeated) previous

homestead law proposals, as they feared free land would attract European immigrants and poor Southern whites to the west.

After the South seceded and their delegates left Congress in 1861, the

Republicans and other supporters from the upper South passed a homestead

act.

The intent of the first Homestead Act, passed in 1862, was to liberalize the homesteading requirements of the Preemption Act of 1841. Its leading advocates were Andrew Johnson, George Henry Evans and Horace Greeley.

The homestead was an area of public land

in the West (usually 160 acres or 65 ha) granted to any US citizen

willing to settle on and farm the land. The law (and those following

it) required a three-step procedure: file an application, improve the land, and file for the patent (deed). Any citizen who had never taken up arms against the U.S. government (including freed slaves after the fourteenth amendment) and was at least 21 years old or the head of a household,

could file an application to claim a federal land grant. Women were

eligible. The occupant had to reside on the land for five years, and

show evidence of having made improvements. The process had to be

complete within seven years.

Southern Homestead Act of 1866

Enacted to allow poor tenant farmers and sharecroppers in the south become land owners in the southern United States

during Reconstruction. It was not very successful, as even the low

prices and fees were often too much for the applicants to afford.

Timber Culture Act of 1873

The Timber Culture Act granted up to 160 acres of land to a

homesteader who would plant at least 40 acres (revised to 10) of trees

over a period of several years. This quarter-section could be added to

an existing homestead claim, offering a total of 320 acres to a settler.

This offered a cheap plot of land to homesteaders.

Kinkaid Amendment of 1904

Recognizing that the Sandhills (Nebraska)

of north-central Nebraska, required more than 160 acres for a claimant

to support a family, Congress passed the Kinkaid Act which granted

larger homestead tracts, up to 640 acres, to homesteaders in Nebraska.

Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909

Because by the early 1900s much of the prime low-lying alluvial land along rivers had been homesteaded, the Enlarged Homestead Act was passed in 1909. To enable dryland farming, it increased the number of acres for a homestead to 320 acres (130 ha) given to farmers who accepted more marginal lands (especially in the Great Plains), which could not be easily irrigated.

A massive influx of these new farmers, combined with

inappropriate cultivation techniques and misunderstanding of the

ecology, led to immense land erosion and eventually the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916

In 1916, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act was passed for settlers seeking 640 acres (260 ha) of public land for ranching purposes.

Subsistence Homesteads provisions under the New Deal – 1930

Typical STA "Jackrabbit" homestead cabin remains in Wonder Valley, California

Renewed interest in homesteading was brought about by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's program of Subsistence Homesteading implemented in the 1930s under the New Deal.

Small Tracts Act: In 1938 Congress passed a law, called the

Small Tract Act (STA) of 1938 — by which it is possible for any citizen

to obtain certain lands from the Federal Government for residence,

recreation, or business purposes. These tracts may not usually be

larger than 5 acres. A 5-acre tract would be one which is 660 feet long

and 330 feet wide, or its equivalent. The property was to be improved

with a building. Starting July 1955, improvement was required to be

minimum of 400 sq. feet of space.

4,000 previously classified Small Tracts were offered at public auction

at fair market value, circa 1958, by the Los Angeles Office of BLM.

Homesteading requirements

The Homestead Acts had few qualifying requirements. A homesteader

had to be the head of the household or at least twenty-one years old.

They had to live on the designated land, build a home, make

improvements, and farm it for a minimum of five years. The filing fee was eighteen dollars (or ten to temporarily hold a claim to the land).

Immigrants, farmers without their own land, single women, and

former slaves could all qualify. The fundamental racial qualification

was that one had to be a citizen, or have filed a declaration of

intention to become a citizen, and so the qualification changed over the

years with the varying legal qualifications for citizenship. African-Americans became qualified with the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. South Asians and East Asians who had been born in the United States became qualified with the decision of United States v. Wong Kim Ark

in 1898, but little high-quality land remained available by that time.

For immigrants the fundamental qualification was that they had to be

permitted to enter the country (which was usually co-extensive with

being allowed to file a declaration of intention to become a citizen). During the 1800s, the bulk of immigrants were from Europe, with immigrants from South Asia and East Asia being largely excluded, and (voluntary) immigrants from Africa were permitted but uncommon.

In practice

Settlers

found land and filed their claims at the regional land office, usually

in individual family units, although others formed closer knit

communities. Often, the homestead consisted of several buildings or

structures besides the main house.

The Homestead Act of 1862 gave rise later to a new phenomenon, large land rushes, such as the Oklahoma Land Runs of the 1880s and 90s.

End of homesteading

Dugout home from a homestead near Pie Town, New Mexico, 1940

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 ended homesteading;

by that time, federal government policy had shifted to retaining

control of western public lands. The only exception to this new policy

was in Alaska, for which the law allowed homesteading until 1986.

The last claim under this Act was made by Ken Deardorff for 80 acres (32 ha) of land on the Stony River

in southwestern Alaska. He fulfilled all requirements of the homestead

act in 1979 but did not receive his deed until May 1988. He is the last

person to receive title to land claimed under the Homestead Acts.

Criticism

The homestead acts were much abused. Although the intent was to grant land for agriculture, in the arid areas east of the Rocky Mountains,

640 acres (260 ha) was generally too little land for a viable farm (at

least prior to major federal public investments in irrigation projects).

In these areas, people manipulated the provisions of the act to gain

control of resources, especially water. A common scheme was for an

individual, acting as a front for a large cattle operation, to file for a

homestead surrounding a water source, under the pretense that the land

was to be used as a farm. Once the land was granted, other cattle

ranchers would be denied the use of that water source, effectively

closing off the adjacent public land to competition. That method was

also used by large businesses and speculators to gain ownership of

timber and oil-producing land. The federal government charged royalties

for extraction of these resources from public lands. On the other hand,

homesteading schemes were generally pointless for land containing

"locatable minerals," such as gold and silver, which could be controlled

through mining claims under the Mining Act of 1872, for which the federal government did not charge royalties.

The government developed no systematic method to evaluate claims

under the homestead acts. Land offices relied on affidavits from

witnesses that the claimant had lived on the land for the required

period of time and made the required improvements. In practice, some of

these witnesses were bribed or otherwise colluded with the claimant.

Although not necessarily fraud, it was common practice for the

eligible children of a large family to claim nearby land as soon as

possible. After a few generations, a family could build up a sizable

estate.

The homesteads were criticized as too small for the environmental

conditions on the Great Plains; a homesteader using 19th-century

animal-powered tilling and harvesting could not have cultivated the 1500

acres later recommended for dry land farming. Some scholars believe the

acreage limits were reasonable when the act was written, but reveal

that no one understood the physical conditions of the plains.

According to Hugh Nibley, much of the rain forest west of Portland, Oregon was acquired by the Oregon Lumber Company by illegal claims under the Act.

Nonetheless, in 1995, a random survey of 178 members of the Economic History Association

found that 70 percent of economists and 84 percent of economic

historians disagreed that "Nineteenth-century U.S. land policy, which

attempted to give away free land, probably represented a net drain on

the productive capacity of the country."

Related acts in other countries

Canada

Similar laws were passed in Canada:

The Legislative Assembly of Ontario passed The Free Grants and Homestead Act in 1868, which introduced a conditional scheme to an existing free grant plan previously authorized by the Province of Canada in The Public Lands Act of 1860. It was extended to include settlement in the Rainy River District under The Rainy River Free Grants and Homestead Act, 1886, These Acts were consolidated in 1913 in The Public Lands Act, which was further extended in 1948 to provide for free grants to former members of the Canadian Forces. The original free grant provisions for settlers were repealed in 1951, and the remaining provisions were repealed in 1961.

The Parliament of Canada passed the Dominion Lands Act in 1872 in order to encourage settlement in the Northwest Territories. Its application was restricted after the passage of the Natural Resources Acts in 1930, and it was finally repealed in 1950.

The Legislative Assembly of Quebec

did not expand the scope of the 1860 Province of Canada Act (which

modern day Quebec was part of in 1860), but did provide in 1868 that

such lands were exempt from seizure, and chattels thereon were also

exempt for the first ten years of occupation.[36] Later known as the Settlers Protection Act, it was repealed in 1984.

Newfoundland and Labrador

provided for free grants of land upon proof of possession for twenty

years prior to 1977, with continuous use for agricultural, business or

residential purposes during that time. Similar programs continued to operate in Alberta and British Columbia until 1970. In the early 21st century, some land is still being granted in the Yukon Territory under its Agricultural Lands Program.

New Zealand

Despite the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi provisions for sale of land, the Māori Land Court decided that all land not cultivated by Māori was 'waste land' and belonged to the Crown without purchase. Most New Zealand provinces had Waste Lands Acts enacted between 1854 and 1877. The 1877 Land Act in Auckland Province used the term Homestead, with allocation administered by a Crown Lands Board. There was similar legislation in Westland. It gave up to 75 acres (30 ha), with settlers

just paying the cost of a survey. They had to live there for five

years, build a house and cultivate a third of the land, if already open,

or a fifth if bush had to be cleared. The land was forfeited if they didn't clear enough bush. This contributed to rapid deforestation.

Elsewhere in the British Empire

Similar in intent, the British Crown Lands Acts

were extended to several of the Empire's territories, and many are

still in effect, to some extent, today. For instance, the Australian selection acts were passed in the various Australian colonies following the first, in 1861, in New South Wales.

In popular culture

- Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie series describes her father and family claiming a homestead in Kansas, and later Dakota Territory. Wilder's daughter Rose Wilder Lane published a novel, Free Land, which describes the trials of homesteaders in what is now South Dakota.

- Willa Cather's novels, O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, feature families homesteading on the Great Plains.

- Oscar Micheaux's novel, The Homesteader: a Novel (1917), is a semi-autobiographical story of an African American homesteader in South Dakota shortly after the turn of the 20th century.

- Kirby Larson's young adult novel, Hattie Big Sky, explores one woman's attempts to "improve" on her family's homestead before the deadline to retain her rights.

- The Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma! is based in the Oklahoma land rush.

- The 1962 Elvis Presley musical film, Follow That Dream, adapted from Pioneer, Go Home! (1959), features a family that homesteads in Florida.

- The movie Far and Away, starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, centers on the main characters' struggle to "obtain their 160 acres."

- The miniseries Centennial depicts the homestead development of an eastern Colorado town.

- The 1953 movie Shane depicts some early homesteaders in Wyoming opposed by a cattle baron who abuse, threatens and terrorizes them, calling them "pig farmers," "sod-busters," "squatters" and other taunts and insults. When the rancher gets violent, the homesteaders are divided over whether to leave or to hold onto their claims. A drifter working on one of the homesteads reluctantly tries to take action.

- The 2016 film The Magnificent Seven, loosely adapted from the 1960 film of the same name, features Sam Chisolm, an African American U.S. Marshal raised on a homestead in Lincoln, Kansas. His family had been lynched in 1867 by former Confederate Army soldiers, hired by a robber baron to drive off settlers and free up real estate on the American frontier.