| Homo sapiens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male and female H s. sapiens (Akha in northern Thailand, 2007 photograph) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: |

H. sapiens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Homo sapiens | |

| Subspecies | |

|

H. s. sapiens †H. s. idaltu †H. s. neanderthalensis(?) †H. s. rhodesiensis(?) (others proposed) | |

Homo sapiens is the only extant human species. The name is Latin for "wise man" and was introduced in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus (who is himself the lectotype for the species).

Extinct species of the genus Homo include Homo erectus, extant during roughly 1.9 to 0.4 million years ago, and a number of other species (by some authors considered subspecies of either H. sapiens or H. erectus). The age of speciation of H. sapiens out of ancestral H. erectus (or an intermediate species such as Homo antecessor) is estimated to have been roughly 350,000 years ago. Sustained archaic admixture is known to have taken place both in Africa and (following the recent Out-Of-Africa expansion) in Eurasia, between about 100,000 and 30,000 years ago.

The term anatomically modern humans (AMH) is used to distinguish H. sapiens having an anatomy consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from varieties of extinct archaic humans. This is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe.

Name and taxonomy

The binomial name Homo sapiens was coined by Linnaeus, 1758. The Latin noun homō (genitive hominis) means "human being", while the participle sapiēns means "discerning, wise, sensible".The species was initially thought to have emerged from a predecessor within the genus Homo around 300,000 to 200,000 years ago. A problem with the morphological classification of "anatomically modern" was that it would not have included certain extant populations. For this reason, a lineage-based (cladistic) definition of H. sapiens has been suggested, in which H. sapiens would by definition refer to the modern human lineage following the split from the Neanderthal lineage. Such a cladistic definition would extend the age of H. sapiens to over 500,000 years.

Extant human populations have historically been divided into subspecies, but since around the 1980s all extant groups have tended to be subsumed into a single species, H. sapiens, avoiding division into subspecies altogether.

Some sources show Neanderthals (H. neanderthalensis) as a subspecies (H. sapiens neanderthalensis). Similarly, the discovered specimens of the H. rhodesiensis species have been classified by some as a subspecies (H. sapiens rhodesiensis), although it remains more common to treat these last two as separate species within the genus Homo rather than as subspecies within H. sapiens.

The subspecies name H. sapiens sapiens is sometimes used informally instead of "modern humans" or "anatomically modern humans". It has no formal authority associated with it. By the early 2000s, it had become common to use H. s. sapiens for the ancestral population of all contemporary humans, and as such it is equivalent to the binomial H. sapiens in the more restrictive sense (considering H. neanderthalensis a separate species).

Age and speciation process

Schematic representation of the emergence of H. sapiens from earlier species of Homo. The horizontal axis represents geographic location; the vertical axis represents time in millions of years ago (blue areas denote the presence of a certain species of Homo at a given time and place; late survival of robust australopithecines alongside Homo is indicated in purple). Based on Springer (2012), Homo heidelbergensis is shown as diverging into Neanderthals, Denisovans and H. sapiens. With the rapid expansion of H. sapiens after 60 kya, Neanderthals, Denisovans and unspecified archaic African hominins are shown as again subsumed into the H. sapiens lineage.

Derivation from H. erectus

A model of the phylogeny of H. sapiens during the Middle Paleolithic. The horizontal axis represents geographic location; the vertical axis represents time in thousands of years ago. Neanderthals, Denisovans and unspecified archaic African hominins are shown as admixed into the H. sapiens lineage. In addition, prehistoric Archaic Human and Eurasian admixture events in modern African populations are indicated.

The speciation of H. sapiens out of archaic human varieties derived from H. erectus is estimated as having taken place over 350,000 years ago, as the Khoisan split from other populations is dated between 260,000 and 350,000 years ago.

An alternative suggestion defines H. sapiens cladistically as including the lineage of modern humans since the split from the lineage of Neanderthals, roughly 500,000 to 800,000 years ago.

The time of divergence between archaic H. sapiens and ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans caused by a genetic bottleneck of the latter was dated at 744,000 years ago, combined with repeated early admixture events and Denisovans diverging from Neanderthals 300 generations after their split from H. sapiens, as calculated by Rogers et al. (2017).

The derivation of a comparatively homogeneous single species of H. sapiens from more diverse varieties of archaic humans (all of which were descended from the early dispersal of H. erectus some 1.8 million years ago) was debated in terms of two competing models during the 1980s: "recent African origin" postulated the emergence of H. sapiens from a single source population in Africa, which expanded and led to the extinction of all other human varieties, while the "multiregional evolution" model postulated the survival of regional forms of archaic humans, gradually converging into the modern human varieties by the mechanism of clinal variation, via genetic drift, gene flow and selection throughout the Pleistocene.

Since the 2000s, the availability of data from archaeogenetics and population genetics has led to the emergence of a much more detailed picture, intermediate between the two competing scenarios outlined above: The recent Out-of-Africa expansion accounts for the predominant part of modern human ancestry, while there were also significant admixture events with regional archaic humans.

Since the 1970s, the Omo remains,

dated to some 195,000 years ago, have often been taken as the

conventional cut-off point for the emergence of "anatomically modern

humans". Since the 2000s, the discovery of older remains with comparable

characteristics, and the discovery of ongoing hybridization between

"modern" and "archaic" populations after the time of the Omo remains,

have opened up a renewed debate on the age of H. sapiens in journalistic publications. H. s. idaltu, dated to 160,000 years ago, has been postulated as an extinct subspecies of H. sapiens in 2003. H. neanderthalensis, which became extinct about 40,000 years ago, has also been classified as a subspecies, H. s. neanderthalensis.

H. heidelbergensis, dated 600,000 to 300,000 years ago,

has long been thought to be a likely candidate for the last common

ancestor of the Neanderthal and modern human lineages. However, genetic

evidence from the Sima de los Huesos fossils published in 2016 seems to suggest that H. heidelbergensis

in its entirety should be included in the Neanderthal lineage, as

"pre-Neanderthal" or "early Neanderthal", while the divergence time

between the Neanderthal and modern lineages has been pushed back to

before the emergence of H. heidelbergensis, to close to 800,000 years ago, the approximate time of disappearance of H. antecessor.

Early Homo sapiens

Skhul V (dated at about 80,000–120,000 years old) exhibiting a mix of archaic and modern traits.

The term Middle Paleolithic is intended to cover the time between the first emergence of H. sapiens (roughly 300,000 years ago) and the emergence of full behavioral modernity (roughly 50,000 years ago, corresponding to the start of the Upper Paleolithic).

Many of the early modern human finds, like those of Omo, Herto, Skhul, Jebel Irhoud and Peștera cu Oase exhibit a mix of archaic and modern traits. Skhul V, for example, has prominent brow ridges and a projecting face. However, the brain case

is quite rounded and distinct from that of the Neanderthals and is

similar to the brain case of modern humans. It is uncertain whether the

robust traits of some of the early modern humans like Skhul V reflects mixed ancestry or retention of older traits.

The "gracile" or lightly built skeleton of anatomically modern

humans has been connected to a change in behavior, including increased

cooperation and "resource transport".

There is evidence that the characteristic human brain

development, especially the prefrontal cortex, was due to "an

exceptional acceleration of metabolome

evolution ... paralleled by a drastic reduction in muscle strength. The

observed rapid metabolic changes in brain and muscle, together with the

unique human cognitive skills and low muscle performance, might reflect

parallel mechanisms in human evolution." The Schöningen spears

and their correlation of finds are evidence that complex technological

skills already existed 300,000 years ago, and are the first obvious

proof of an active (big game) hunt. H. heidelbergensis

already had intellectual and cognitive skills like anticipatory

planning, thinking and acting that so far have only been attributed to

modern man.

The ongoing admixture events within anatomically modern human

populations make it difficult to estimate the age of the matrilinear and

patrilinear most recent common ancestors of modern populations (Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal Adam).

Estimates of the age of Y-chromosomal Adam have been pushed back

significantly with the discovery of an ancient Y-chromosomal lineage in

2013, to likely beyond 300,000 years ago.

There have, however, been no reports of the survival of Y-chromosomal

or mitochondrial DNA clearly deriving from archaic humans (which would

push back the age of the most recent patrilinear or matrilinear ancestor

beyond 500,000 years).

Fossil teeth found at Qesem Cave

(Israel) and dated to between 400,000 and 200,000 years ago have been

compared to the dental material from the younger (120,000–80,000 years

ago) Skhul and Qafzeh hominins.

Dispersal and archaic admixture

Overview map of the peopling of the world by anatomically modern humans (numbers indicate dates in thousands of years ago [ka])

Dispersal of early H. sapiens begins soon after its emergence, as evidenced by the North African Jebel Irhoud finds (dated to between 280,000 and 350,000 years ago). There is indirect evidence for modern human presence in West Asia around 270,000 years ago and Dali Man from China is dated at 260,000 years ago.

Among extant populations, the Khoi-San (or "Capoid")

hunters-gatherers of Southern Africa may represent the human population

with the earliest possible divergence within the group Homo sapiens sapiens.

Their separation time has been estimated in a 2017 study to be as long

as between 260,000 and 350,000 years ago, compatible with the estimated

age of H. sapiens. H. s. idaltu, found at Middle Awash in Ethiopia, lived about 160,000 years ago, and H. sapiens lived at Omo Kibish in Ethiopia about 195,000 years ago. Fossil evidence for modern human presence in West Asia is ascertained for 177,000 years ago, and disputed fossil evidence suggests expansion as far as East Asia by 120,000 years ago.

In July 2019, anthropologists reported the discovery of 210,000 year old remains of a H. sapiens and 170,000 year old remains of a H. neanderthalensis in Apidima Cave, Peloponnese, Greece, more than 150,000 years older than previous H. sapiens finds in Europe.

A significant dispersal event, within Africa and to West Asia, is associated with the African megadroughts during MIS 5, beginning 130,000 years ago.

A 2011 study located the origin of basal population of contemporary

human populations at 130,000 years ago, with the Khoi-San representing

an "ancestral population cluster" located in southwestern Africa (near

the coastal border of Namibia and Angola).

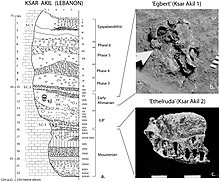

Layer sequence at Ksar Akil in the Levantine corridor, and discovery of two fossils of Homo sapiens, dated to 40,800 to 39,200 years BP for "Egbert",and 42,400–41,700 BP for "Ethelruda".

While early modern human expansion in Sub-Saharan Africa

before 130 kya persisted, early expansion to North Africa and Asia

appears to have mostly disappeared by the end of MIS5 (75,000 years

ago), and is known only from fossil evidence and from archaic admixture. Asia was re-populated by early modern humans in the so-called "recent out-of-Africa migration" post-dating MIS5, beginning around 70,000 years ago. In this expansion, bearers of mt-DNA haplogroup L3 left East Africa, likely reaching Arabia via the Bab-el-Mandeb, and in the Great Coastal Migration spread to South Asia, Maritime South Asia and Oceania by 65,000 years ago, while Europe, East and North Asia, and possibly the Americas, were reached by 50,000 years ago.

Evidence for the overwhelming contribution of this "recent" (L3-derived) expansion to all non-African populations was established based on mitochondrial DNA, combined with evidence based on physical anthropology of archaic specimens, during the 1990s and 2000s. The assumption of complete replacement has been revised in the 2010s with the discovery of admixture events (introgression) of populations of H. sapiens

with populations of archaic humans over the period of between roughly

100,000 and 30,000 years ago, both in Eurasia and in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Neanderthal admixture,

in the range of 1-4%, is found in all modern populations outside of

Africa, including in Europeans, Asians, Papuan New Guineans, Australian

Aboriginals, and Native Americans. This suggests that interbreeding between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans took place after the recent "out of Africa" migration, likely between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago.

Recent admixture analyses have added to the complexity, finding that

Eastern Neanderthals derive up to 2% of their ancestry from anatomically

modern humans who left Africa some 100 kya. The extent of Neanderthal admixture (and introgression

of genes acquired by admixture) varies significantly between

contemporary racial groups, being absent in Africans, intermediate in

Europeans and highest in East Asians. Certain genes related to UV-light

adaptation introgressed from Neanderthals have been found to have been

selected for in East Asians specifically from 45,000 years ago until

around 5,000 years ago. The extent of archaic admixture is of the order of about 1% to 4% in Europeans and East Asians, and highest among Melanesians (Denisova hominin admixture), at 4% to 6%. Cumulatively, about 20% of the Neanderthal genome is estimated to remain present spread in contemporary populations.

Anatomy

Known

archaeological remains of Anatomically Modern Humans in Europe and

Africa, directly dated, calibrated carbon dates as of 2013.

Generally, modern humans are more lightly built (or more "gracile") than the more "robust" archaic humans. Nevertheless, contemporary humans exhibit high variability in many physiological traits,

and may exhibit remarkable "robustness". There are still a number of

physiological details which can be taken as reliably differentiating the

physiology of Neanderthals vs. anatomically modern humans.

Anatomical modernity

The term "anatomically modern humans" (AMH) is used with varying

scope depending on context, to distinguish "anatomically modern" Homo sapiens from archaic humans such as Neanderthals and Middle and Lower Paleolithic hominins with transitional features intermediate between H. erectus, Neanderthals and early AMH called archaic Homo sapiens. In a convention popular in the 1990s, Neanderthals were classified as a subspecies of H. sapiens, as H. s. neanderthalensis, while AMH (or European early modern humans, EEMH) was taken to refer to "Cro-Magnon" or H. s. sapiens. Under this nomenclature (Neanderthals considered H. sapiens), the term "anatomically modern Homo sapiens" (AMHS) has also been used to refer to EEMH ("Cro-Magnons"). It has since become more common to designate Neanderthals as a separate species, H. neanderthalensis, so that AMH in the European context refers to H. sapiens (but the question is by no means resolved).

In this more narrow definition of H. sapiens, the subspecies H. s. idaltu, discovered in 2003, also falls under the umbrella of "anatomically modern". The recognition of H. s. idaltu as a valid subspecies of the anatomically modern human lineage would justify the description of contemporary humans with the subspecies name H. s. sapiens.

A further division of AMH into "early" or "robust" vs.

"post-glacial" or "gracile" subtypes has since been used for

convenience. The emergence of "gracile AMH" is taken to reflect a

process towards a smaller and more fine-boned skeleton beginning around

50,000–30,000 years ago.

Braincase anatomy

Anatomical comparison of skulls of H. sapiens (left) and H. neanderthalensis (right)

(in Cleveland Museum of Natural History)

Features compared are the braincase shape, forehead, browridge, nasal bone, projection, cheek bone angulation, chin and occipital contour

(in Cleveland Museum of Natural History)

Features compared are the braincase shape, forehead, browridge, nasal bone, projection, cheek bone angulation, chin and occipital contour

The cranium lacks a pronounced occipital bun

in the neck, a bulge that anchored considerable neck muscles in

Neanderthals. Modern humans, even the earlier ones, generally have a

larger fore-brain than the archaic people, so that the brain sits above

rather than behind the eyes. This will usually (though not always) give a

higher forehead, and reduced brow ridge.

Early modern people and some living people do however have quite

pronounced brow ridges, but they differ from those of archaic forms by

having both a supraorbital foramen or notch, forming a groove through the ridge above each eye.

This splits the ridge into a central part and two distal parts. In

current humans, often only the central section of the ridge is preserved

(if it is preserved at all). This contrasts with archaic humans, where

the brow ridge is pronounced and unbroken.

Modern humans commonly have a steep, even vertical forehead whereas their predecessors had foreheads that sloped strongly backwards. According to Desmond Morris, the vertical forehead in humans plays an important role in human communication through eyebrow movements and forehead skin wrinkling.

Brain size in both Neanderthals and AMH is significantly larger on average (but overlapping in range) than brain size in H. erectus.

Neanderthal and AMH brain sizes are in the same range, but there are

differences in the relative sizes of individual brain areas, with

significantly larger visual systems in Neanderthals than in AMH.

Jaw anatomy

Compared to archaic people, anatomically modern humans have smaller, differently shaped teeth.

This results in a smaller, more receded dentary, making the rest of the

jaw-line stand out, giving an often quite prominent chin. The central

part of the mandible forming the chin carries a triangularly shaped area

forming the apex of the chin called the mental trigon, not found in archaic humans.

Particularly in living populations, the use of fire and tools requires

fewer jaw muscles, giving slender, more gracile jaws. Compared to

archaic people, modern humans have smaller, lower faces.

Body skeleton structure

The body skeletons of even the earliest and most robustly built

modern humans were less robust than those of Neanderthals (and from what

little we know from Denisovans), having essentially modern proportions.

Particularly regarding the long bones of the limbs, the distal bones

(the radius/ulna and tibia/fibula) are nearly the same size or slightly shorter than the proximal bones (the humerus and femur).

In ancient people, particularly Neanderthals, the distal bones were

shorter, usually thought to be an adaptation to cold climate. The same adaptation can be found in some modern people living in the polar regions.

Height

ranges overlap between Neanderthals and AMH, with Neanderthal averages

cited as 164 to 168 cm (65 to 66 in) and 152 to 156 cm (60 to 61 in) for

males and females, respectively. By comparison, contemporary national averages

range between 158 to 184 cm (62 to 72 in) in males and 147 to 172 cm

(58 to 68 in) in females. Neanderthal ranges approximate the height

distribution measured among Malay people, for one.

Recent evolution

Following the peopling of Africa some 130,000 years ago, and the recent Out-of-Africa expansion some 70,000 to 50,000 years ago, some sub-populations of H. sapiens have been essentially isolated for tens of thousands of years prior to the early modern Age of Discovery. Combined with archaic admixture this has resulted in significant genetic variation, which in some instances has been shown to be the result of directional selection taking place over the past 15,000 years, i.e. significantly later than possible archaic admixture events.

Some climatic adaptations, such as high-altitude adaptation in humans, are thought to have been acquired by archaic admixture. Introgression of genetic variants acquired by Neanderthal admixture have different distributions in European and East Asians,

reflecting differences in recent selective pressures. A 2014 study

reported that Neanderthal-derived variants found in East Asian

populations showed clustering in functional groups related to immune and haematopoietic pathways, while European populations showed clustering in functional groups related to the lipid catabolic process. A 2017 study found correlation of Neanderthal admixture in phenotypic traits in modern European populations.

Physiological or phenotypical changes have been traced to Upper Paleolithic mutations, such as the East Asian variant of the EDAR gene, dated to c. 35,000 years ago.

Recent divergence of Eurasian lineages was sped up significantly during the Last Glacial Maximum, the Mesolithic and the Neolithic, due to increased selection pressures and due to founder effects associated with migration. Alleles predictive of light skin have been found in Neanderthals, but the alleles for light skin in Europeans and East Asians, associated with KITLG and ASIP, are (as of 2012) thought to have not been acquired by archaic admixture but recent mutations since the LGM. Phenotypes associated with the "white" or "Caucasian" populations of Western Eurasian stock emerge during the LGM, from about 19,000 years ago. Average cranial capacity in modern human populations varies in the range of 1,200 to 1,450 cm3

(adult male averages). Larger cranial volume is associated with

climatic region, the largest averages being found in populations of Siberia and the Arctic. Both Neanderthal and EEMH

had somewhat larger cranial volumes on average than modern Europeans,

suggesting the relaxation of selection pressures for larger brain volume

after the end of the LGM.

Examples for still later adaptations related to agriculture and animal domestication including East Asian types of ADH1B associated with rice domestication, or lactase persistence, are due to recent selection pressures.

An even more recent adaptation has been proposed for the Austronesian Sama-Bajau, developed under selection pressures associated with subsisting on freediving over the past thousand years or so.

Behavioral modernity

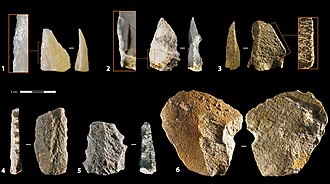

Lithic Industries of early Homo sapiens at Blombos Cave (M3 phase, MIS 5), Southern Cape, South Africa (c. 105 – 90 Ka)

Behavioral modernity, involving the development of language, figurative art and early forms of religion (etc.) is taken to have arisen before 40,000 years ago, marking the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic (in African contexts also known as the Later Stone Age).

There is considerable debate regarding whether the earliest

anatomically modern humans behaved similarly to recent or existing

humans. Behavioral modernity is taken to include fully developed language (requiring the capacity for abstract thought), artistic expression, early forms of religious behavior, increased cooperation and the formation of early settlements, and the production of articulated tools from lithic cores, bone or antler. The term Upper Paleolithic is intended to cover the period since the rapid expansion of modern humans throughout Eurasia, which coincides with the first appearance of Paleolithic art such as cave paintings and the development of technological innovation such as the spear-thrower.

The Upper Paleolithic begins around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, and

also coincides with the disappearance of archaic humans such as the Neanderthals.

Bifacial silcrete point of early Homo sapiens, from M1 phase (71,000 BCE) layer of Blombos Cave, South Africa

The term "behavioral modernity" is somewhat disputed. It is most

often used for the set of characteristics marking the Upper Paleolithic,

but some scholars use "behavioral modernity" for the emergence of H. sapiens around 200,000 years ago, while others use the term for the rapid developments occurring around 50,000 years ago. It has been proposed that the emergence of behavioral modernity was a gradual process.

In January 2018, it was announced that modern human finds at

Misliya cave, Israel, in 2002, had been dated to around 185,000 years

ago, the earliest evidence of their out of Africa migration.

The earliest H. sapiens (AMH) found in Europe are the "Cro-Magnon" (named after the site of first discovery in France), beginning about 40,000 to 35,000 years ago. These are also known as "European early modern humans" in contrast to the preceding Neanderthals.

Claimed "Oldest known drawing by human hands", discovered in Blombos Cave in South Africa. Estimated to be a 73,000 years old work of a Homo sapiens.

The International Space Station, one of the latest creations of Homo sapiens

The equivalent of the Eurasian Upper Paleolithic in African archaeology is known as the Later Stone Age,

also beginning roughly 40,000 years ago. While most clear evidence for

behavioral modernity uncovered from the later 19th century was from

Europe, such as the Venus figurines and other artefacts from the Aurignacian,

more recent archaeological research has shown that all essential

elements of the kind of material culture typical of contemporary San hunter-gatherers in Southern Africa was also present by least 40,000 years ago, including digging sticks of similar materials used today, ostrich egg shell beads, bone arrow heads with individual maker's marks etched and embedded with red ochre, and poison applicators.

There is also a suggestion that "pressure flaking best explains the

morphology of lithic artifacts recovered from the c. 75-ka Middle Stone

Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa. The technique was used during

the final shaping of Still Bay bifacial points made on heat‐treated

silcrete."

Both pressure flaking and heat treatment of materials were previously

thought to have occurred much later in prehistory, and both indicate a

behaviourally modern sophistication in the use of natural materials.

Further reports of research on cave sites along the southern African

coast indicate that "the debate as to when cultural and cognitive

characteristics typical of modern humans first appeared" may be coming

to an end, as "advanced technologies with elaborate chains of

production" which "often demand high-fidelity transmission and thus

language" have been found at Pinnacle Point Site 5–6. These have been

dated to approximately 71,000 years ago. The researchers suggest that

their research "shows that microlithic technology originated early in

South Africa, evolved over a vast time span (c. 11,000 years), and was

typically coupled to complex heat treatment that persisted for nearly

100,000 years. Advanced technologies in Africa

were early and enduring; a small sample of excavated sites in Africa is

the best explanation for any perceived 'flickering' pattern."

These results suggest that Late Stone Age foragers in Sub-Saharan

Africa had developed modern cognition and behaviour by at least 50,000

years ago.

The change in behavior has been speculated to have been a consequence

of an earlier climatic change to much drier and colder conditions

between 135,000 and 75,000 years ago.

This might have led to human groups who were seeking refuge from the

inland droughts, expanded along the coastal marshes rich in shellfish

and other resources. Since sea levels were low due to so much water tied

up in glaciers, such marshlands would have occurred all along the southern coasts of Eurasia. The use of rafts

and boats may well have facilitated exploration of offshore islands and

travel along the coast, and eventually permitted expansion to New

Guinea and then to Australia.