Medium close-up view, captured with a 70 mm camera, shows tethered satellite system deployment.

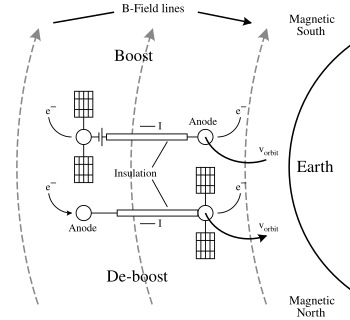

Electrodynamic tethers (EDTs) are long conducting wires, such as one deployed from a tether satellite, which can operate on electromagnetic principles as generators, by converting their kinetic energy to electrical energy, or as motors, converting electrical energy to kinetic energy. Electric potential is generated across a conductive tether by its motion through a planet's magnetic field.

A number of missions have demonstrated electrodynamic tethers in space, most notably the TSS-1, TSS-1R, and Plasma Motor Generator (PMG) experiments.

Tether propulsion

As part of a tether propulsion system, crafts can use long, strong conductors (though not all tethers are conductive) to change the orbits of spacecraft. It has the potential to make space travel significantly cheaper. When direct current is applied to the tether, it exerts a Lorentz force

against the magnetic field, and the tether exerts a force on the

vehicle. It can be used either to accelerate or brake an orbiting

spacecraft.

In 2012, the company Star Technology and Research was awarded a $1.9 million contract to qualify a tether propulsion system for orbital debris removal.

Uses for ED tethers

Over the years, numerous applications for electrodynamic tethers have

been identified for potential use in industry, government, and

scientific exploration. The table below is a summary of some of the

potential applications proposed thus far. Some of these applications are

general concepts, while others are well-defined systems. Many of these

concepts overlap into other areas; however, they are simply placed under

the most appropriate heading for the purposes of this table. All of the

applications mentioned in the table are elaborated upon in the Tethers

Handbook.

Three fundamental concepts that tethers possess, are gravity gradients,

momentum exchange, and electrodynamics. Potential tether applications

can be seen below:

Electrodynamic tether fundamentals

Illustration of the EDT concept

The choice of the metal conductor to be used in an electrodynamic tether is determined by a variety of factors. Primary factors usually include high electrical conductivity, and low density. Secondary factors, depending on the application, include cost, strength, and melting point.

An electromotive force (EMF) is generated across a tether element

as it moves relative to a magnetic field. The force is given by Faraday's Law of Induction:

Without loss of generality, it is assumed the tether system is in Earth orbit

and it moves relative to Earth's magnetic field. Similarly, if current

flows in the tether element, a force can be generated in accordance

with the Lorentz force equation

In self-powered mode (deorbit

mode), this EMF can be used by the tether system to drive the current

through the tether and other electrical loads (e.g. resistors,

batteries), emit electrons at the emitting end, or collect electrons at

the opposite. In boost mode, on-board power supplies must overcome this

motional EMF to drive current in the opposite direction, thus creating a

force in the opposite direction, as seen in below figure, and boosting

the system.

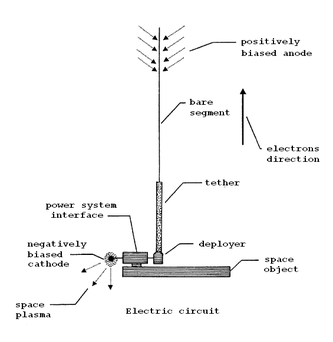

Take, for example, the NASA Propulsive Small Expendable Deployer System (ProSEDS) mission as seen in above figure. At 300 km altitude, the Earth's magnetic field, in the north-south direction, is approximately 0.18–0.32 gauss up to ~40° inclination, and the orbital velocity with respect to the local plasma is about 7500 m/s. This results in a Vemf

range of 35–250 V/km along the 5 km length of tether. This EMF

dictates the potential difference across the bare tether which controls

where electrons are collected and / or repelled. Here, the ProSEDS

de-boost tether system is configured to enable electron collection to

the positively biased higher altitude section of the bare tether, and

returned to the ionosphere at the lower altitude end. This flow of

electrons through the length of the tether in the presence of the

Earth's magnetic field creates a force that produces a drag thrust that

helps de-orbit the system, as given by the above equation.

The boost mode is similar to the de-orbit mode, except for the fact that

a High Voltage Power Supply (HVPS) is also inserted in series with the

tether system between the tether and the higher positive potential end.

The power supply voltage must be greater than the EMF and the polar

opposite. This drives the current in the opposite direction, which in

turn causes the higher altitude end to be negatively charged, while the

lower altitude end is positively charged(Assuming a standard east to

west orbit around Earth).

To further emphasize the de-boosting phenomenon, a schematic

sketch of a bare tether system with no insulation (all bare) can be seen

in below figure.

Current and Voltage plots vs. distance of a bare tether operating in generator (de-boost) mode.

The top of the diagram, point A, represents the electron collection end. The bottom of the tether, point C, is the electron emission end. Similarly, and represent the potential difference from their respective tether ends to the plasma, and is the potential anywhere along the tether with respect to the plasma. Finally, point B is the point at which the potential of the tether is equal to the plasma. The location of point B will vary depending on the equilibrium state of the tether, which is determined by the solution of Kirchhoff's voltage law (KVL)

and Kirchhoff's current law (KCL)

along the tether. Here , , and describe the current gain from point A to B, the current lost from point B to C, and the current lost at point C, respectively.

Since the current is continuously changing along the bare length

of the tether, the potential loss due to the resistive nature of the

wire is represented as . Along an infinitesimal section of tether, the resistance multiplied by the current traveling across that section is the resistive potential loss.

After evaluating KVL & KCL for the system, the results will

yield a current and potential profile along the tether, as seen in above

figure. This diagram shows that, from point A of the tether down to point B, there is a positive potential bias, which increases the collected current. Below that point, the

becomes negative and the collection of ion current begins. Since it

takes a much greater potential difference to collect an equivalent

amount of ion current (for a given area), the total current in the

tether is reduced by a smaller amount. Then, at point C, the remaining current in the system is drawn through the resistive load (), and emitted from an electron emissive device (), and finally across the plasma sheath (). The KVL voltage loop is then closed in the ionosphere where the potential difference is effectively zero.

Due to the nature of the bare EDTs, it is often not optional to

have the entire tether bare. In order to maximize the thrusting

capability of the system a significant portion of the bare tether should

be insulated. This insulation amount depends on a number of effects,

some of which are plasma density, the tether length and width, the

orbiting velocity, and the Earth's magnetic flux density.

Tethers as generators

A

space object, i.e. a satellite in Earth orbit, or any other space

object either natural or man made, is physically connected to the tether

system. The tether system comprises a deployer from which a conductive

tether having a bare segment extends upward from space object. The

positively biased anode end of tether collects electrons from the

ionosphere as space object moves in direction across the Earth's

magnetic field. These electrons flow through the conductive structure of

the tether to the power system interface, where it supplies power to an

associated load, not shown. The electrons then flow to the negatively

biased cathode where electrons are ejected into the space plasma, thus

completing the electric circuit. (source: U.S. Patent 6,116,544,

"Electrodynamic Tether And Method of Use".)

An electrodynamic tether is attached to an object, the tether being

oriented at an angle to the local vertical between the object and a

planet with a magnetic field. The tether's far end can be left bare,

making electrical contact with the ionosphere. When the tether intersects the planet's magnetic field,

it generates a current, and thereby converts some of the orbiting

body's kinetic energy to electrical energy. Functionally, electrons

flow from the space plasma into the conductive tether, are passed

through a resistive load in a control unit and are emitted into the

space plasma by an electron emitter as free electrons. As a result of

this process, an electrodynamic force acts on the tether and attached

object, slowing their orbital motion. In a loose sense, the process can

be likened to a conventional windmill- the drag force of a resistive

medium(air or, in this case, the magnetosphere) is used to convert the

kinetic energy of relative motion(wind, or the satellite's momentum)

into electricity. In principle, compact high-current tether power

generators are possible and, with basic hardware, tens, hundreds, and

thousands of kilowatts appears to be attainable.

Voltage and current

NASA

has conducted several experiments with Plasma Motor Generator (PMG)

tethers in space. An early experiment used a 500-meter conducting

tether. In 1996, NASA conducted an experiment with a 20,000-meter

conducting tether. When the tether was fully deployed during this test,

the orbiting tether generated a potential of 3,500 volts. This

conducting single-line tether was severed after five hours of

deployment. It is believed that the failure was caused by an electric

arc generated by the conductive tether's movement through the Earth's

magnetic field.

When a tether is moved at a velocity (v) at right angles to the Earth's magnetic field (B), an electric field is observed in the tether's frame of reference. This can be stated as:

- E = v * B = vB

The direction of the electric field (E) is at right angles to both the tether's velocity (v) and magnetic field (B).

If the tether is a conductor, then the electric field leads to the

displacement of charges along the tether. Note that the velocity used in

this equation is the orbital velocity of the tether. The rate of

rotation of the Earth, or of its core, is not relevant. In this regard,

see also homopolar generator.

Voltage across conductor

With a long conducting wire of length L, an electric field E is generated in the wire. It produces a voltage V between the opposite ends of the wire. This can be expressed as:

where the angle τ is between the length vector (L) of the tether and the electric field vector (E), assumed to be in the vertical direction at right angles to the velocity vector (v) in plane and the magnetic field vector (B) is out of the plane.

Current in conductor

An electrodynamic tether can be described as a type of thermodynamically "open system".

Electrodynamic tether circuits cannot be completed by simply using

another wire, since another tether will develop a similar voltage.

Fortunately, the Earth's magnetosphere is not "empty", and, in

near-Earth regions (especially near the Earth's atmosphere) there exist

highly electrically conductive plasmas which are kept partially ionized by solar radiation or other radiant energy.

The electron and ion density varies according to various factors, such

as the location, altitude, season, sunspot cycle, and contamination

levels. It is known that a positively charged bare conductor

can readily remove free electrons out of the plasma. Thus, to complete

the electrical circuit, a sufficiently large area of uninsulated

conductor is needed at the upper, positively charged end of the tether,

thereby permitting current to flow through the tether.

However, it is more difficult for the opposite (negative) end of

the tether to eject free electrons or to collect positive ions from the

plasma. It is plausible that, by using a very large collection area at

one end of the tether, enough ions can be collected to permit

significant current through the plasma. This was demonstrated during the

Shuttle orbiter's TSS-1R mission, when the shuttle itself was used as a

large plasma contactor to provide over an ampere of current. Improved methods include creating an electron emitter, such as a thermionic cathode, plasma cathode, plasma contactor, or field electron emission

device. Since both ends of the tether are "open" to the surrounding

plasma, electrons can flow out of one end of the tether while a

corresponding flow of electrons enters the other end. In this fashion,

the voltage that is electromagnetically induced within the tether can

cause current to flow through the surrounding space environment, completing an electrical circuit through what appears to be, at first glance, an open circuit.

Tether current

The amount of current (I) flowing through a tether depends on various factors. One of these is the circuit's total resistance (R). The circuit's resistance consist of three components:

- the effective resistance of the plasma,

- the resistance of the tether, and

- a control variable resistor.

In addition, a parasitic load

is needed. The load on the current may take the form of a charging

device which, in turn, charges reserve power sources such as batteries.

The batteries in return will be used to control power and communication

circuits, as well as drive the electron emitting devices at the negative

end of the tether. As such the tether can be completely self-powered,

besides the initial charge in the batteries to provide electrical power

for the deployment and startup procedure.

The charging battery load can be viewed as a resistor which

absorbs power, but stores this for later use (instead of immediately

dissipating heat). It is included as part of the "control resistor". The

charging battery load is not treated as a "base resistance" though, as

the charging circuit can be turned off at any time. When off, the

operations can be continued without interruption using the power stored

in the batteries.

Current collection / emission for an EDT system: theory and technology

Understanding

electron and ion current collection to and from the surrounding ambient

plasma is critical for most EDT systems. Any exposed conducting

section of the EDT system can passively ('passive' and 'active' emission

refers to the use of pre-stored energy in order to achieve the desired

effect) collect electron or ion current, depending on the electric

potential of the spacecraft body with respect to the ambient plasma. In

addition, the geometry of the conducting body plays an important role

in the size of the sheath and thus the total collection capability. As a

result, there are a number of theories for the varying collection

techniques.

The primary passive processes that control the electron and ion

collection on an EDT system are thermal current collection, ion ram

collection affects, electron photoemission, and possibly secondary

electron and ion emission. In addition, the collection along a thin

bare tether is described using orbital motion limited (OML) theory as

well as theoretical derivations from this model depending on the

physical size with respect to the plasma Debye length. These processes

take place all along the exposed conducting material of the entire

system. Environmental and orbital parameters can significantly

influence the amount collected current. Some important parameters

include plasma density, electron and ion temperature, ion molecular

weight, magnetic field strength and orbital velocity relative to the

surrounding plasma.

Then there is active collection and emission techniques involved

in an EDT system. This occurs through devices such as a hollow cathode

plasma contactors, thermionic cathodes,

and field emitter arrays. The physical design of each of these

structures as well as the current emission capabilities are thoroughly

discussed.

Bare conductive tethers

The concept of current collection to a bare conducting tether was first formalized by Sanmartin and Martinez-Sanchez.

They note that the most area efficient current collecting cylindrical

surface is one that has an effective radius less than ~1 Debye length

where current collection physics is known as orbital motion limited

(OML) in a collisionless plasma. As the effective radius of the bare

conductive tether increases past this point then there are predictable

reductions in collection efficiency compared to OML theory. In addition

to this theory (which has been derived for a non-flowing plasma),

current collection in space occurs in a flowing plasma, which introduces

another collection affect. These issues are explored in greater detail

below.

Orbit motion limited (OML) theory

The electron Debye length is defined as the characteristic shielding distance in a plasma, and is described by the equation

This distance, where all electric fields in the plasma resulting from

the conductive body have fallen off by 1/e, can be calculated. OML

theory

is defined with the assumption that the electron Debye length is equal

to or larger than the size of the object and the plasma is not flowing.

The OML regime occurs when the sheath becomes sufficiently thick such

that orbital effects become important in particle collection. This

theory accounts for and conserves particle energy and angular momentum.

As a result, not all particles that are incident onto the surface of

the thick sheath are collected. The voltage of the collecting structure

with respect to the ambient plasma, as well as the ambient plasma

density and temperature, determines the size of the sheath. This

accelerating (or decelerating) voltage combined with the energy and

momentum of the incoming particles determines the amount of current

collected across the plasma sheath.

The orbital-motion-limit regime is attained when the cylinder

radius is small enough such that all incoming particle trajectories that

are collected are terminated on the cylinder's surface are connected to

the background plasma, regardless of their initial angular momentum

(i.e., none are connected to another location on the probe's surface).

Since, in a quasi-neutral collisionless plasma, the distribution

function is conserved along particle orbits, having all “directions of

arrival” populated corresponds to an upper limit on the collected

current per unit area (not total current).

In an EDT system, the best performance for a given tether mass is

for a tether diameter chosen to be smaller than an electron Debye

length for typical ionospheric ambient conditions (Typical ionospheric

conditions in the from 200 to 2000 km altitude range, have a T_e ranging

from 0.1 eV to 0.35 eV, and n_e ranging from 10^10 m^-3 to 10^12 m^-3

), so it is therefore within the OML regime. Tether geometries outside

this dimension have been addressed.

OML collection will be used as a baseline when comparing the current

collection results for various sample tether geometries and sizes.

In 1962 Gerald H. Rosen derived the equation that is now known as the OML theory of dust charging. According to Robert Merlino of the University of Iowa, Rosen seems to have arrived at the equation 30 years before anyone else.

Deviations from OML theory in a non-flowing plasma

For

a variety of practical reasons, current collection to a bare EDT does

not always satisfy the assumption of OML collection theory.

Understanding how the predicted performance deviates from theory is

important for these conditions. Two commonly proposed geometries for an

EDT involve the use of a cylindrical wire and a flat tape. As long as

the cylindrical tether is less than one Debye length in radius, it will

collect according to the OML theory. However, once the width exceeds

this distance, then the collection increasingly deviates from this

theory. If the tether geometry is a flat tape, then an approximation

can be used to convert the normalized tape width to an equivalent

cylinder radius. This was first done by Sanmartin and Estes and more recently using the 2-Dimensional Kinetic Plasma Solver (KiPS 2-D) by Choiniere et al.

Flowing plasma effect

There

is at present, no closed-form solution to account for the effects of

plasma flow relative to the bare tether. However, numerical simulation

has been recently developed by Choiniere et al. using KiPS-2D which can

simulate flowing cases for simple geometries at high bias potentials. This flowing plasma analysis as it applies to EDTs have been discussed. This phenomenon is presently being investigated through recent work, and is not fully understood.

Endbody collection

This

section discusses the plasma physics theory that explains passive

current collection to a large conductive body which will be applied at

the end of an ED tether. When the size of the sheath is much smaller

than the radius of the collecting body then depending on the polarity of

the difference between the potential of the tether and that of the

ambient plasma, (V – Vp), it is assumed that all of the incoming

electrons or ions that enter the plasma sheath are collected by the

conductive body.

This 'thin sheath' theory involving non-flowing plasmas is discussed,

and then the modifications to this theory for flowing plasma is

presented. Other current collection mechanisms will then be discussed.

All of the theory presented is used towards developing a current

collection model to account for all conditions encountered during an EDT

mission.

Passive collection theory

In

a non-flowing quasi-neutral plasma with no magnetic field, it can be

assumed that a spherical conducting object will collect equally in all

directions. The electron and ion collection at the end-body is governed

by the thermal collection process, which is given by Ithe and Ithi.

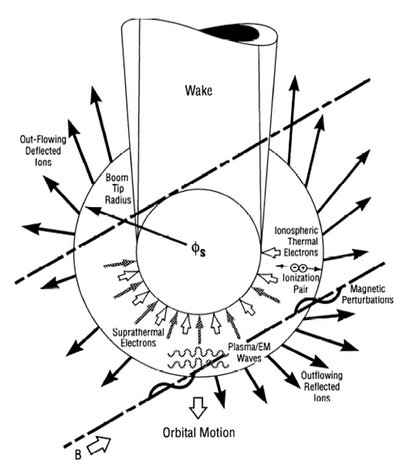

Flowing plasma electron collection mode

The

next step in developing a more realistic model for current collection

is to include the magnetic field effects and plasma flow effects.

Assuming a collisionless plasma, electrons and ions gyrate around

magnetic field lines as they travel between the poles around the Earth

due to magnetic mirroring forces and gradient-curvature drift.

They gyrate at a particular radius and frequency dependence upon their

mass, the magnetic field strength, and energy. These factors must be

considered in current collection models.

A

composite schematic of the complex array of physical effects and

characteristics observed in the near environment of the TSS satellite.

Flowing plasma ion collection model

When

the conducting body is negatively biased with respect to the plasma and

traveling above the ion thermal velocity, there are additional

collection mechanisms at work. For typical Low Earth Orbits (LEOs),

between 200 km and 2000 km,

the velocities in an inertial reference frame range from 7.8 km/s to

6.9 km/s for a circular orbit and the atmospheric molecular weights

range from 25.0 amu (O+, O2+, & NO+) to 1.2 amu (mostly H+),

respectively.

Assuming that the electron and ion temperatures range from ~0.1 eV to

0.35 eV, the resulting ion velocity ranges from 875 m/s to 4.0 km/s from

200 km to 2000 km altitude, respectively. The electrons are traveling

at approximately 188 km/s throughout LEO. This means that the orbiting

body is traveling faster than the ions and slower than the electrons, or

at a mesosonic speed. This results in a unique phenomenon whereby the

orbiting body 'rams' through the surrounding ions in the plasma creating

a beam like effect in the reference frame of the orbiting body.

Porous endbodies

Porous

endbodies have been proposed as a way to reduce the drag of a

collecting endbody while ideally maintaining a similar current

collection. They are often modeled as solid endbodies, except they are a

small percentage of the solid spheres surface area. This is, however,

an extreme oversimplification of the concept. Much has to be learned

about the interactions between the sheath structure, the geometry of the

mesh, the size of the endbody, and its relation to current collection.

This technology also has the potential to resolve a number of issues

concerning EDTs. Diminishing returns with collection current and drag

area have set a limit that porous tethers might be able to overcome.

Work has been accomplished on current collection using porous spheres,

by Stone et al. and Khazanov et al.

It has been shown that the maximum current collected by a grid

sphere compared to the mass and drag reduction can be estimated. The

drag per unit of collected current for a grid sphere with a transparency

of 80 to 90% is approximately 1.2 – 1.4 times smaller than that of a

solid sphere of the same radius. The reduction in mass per unit volume,

for this same comparison, is 2.4 – 2.8 times.

Other current collection methods

In

addition to the electron thermal collection, other processes that could

influence the current collection in an EDT system are photoemission,

secondary electron emission, and secondary ion emission. These effects

pertain to all conducting surfaces on an EDT system, not just the

end-body.

Space charge limits across plasma sheaths

In

any application where electrons are emitted across a vacuum gap, there

is a maximum allowable current for a given bias due to the self

repulsion of the electron beam. This classical 1-D space charge limit

(SCL) is derived for charged particles of zero initial energy, and is

termed the Child-Langmuir Law.

This limit depends on the emission surface area, the potential

difference across the plasma gap and the distance of that gap. Further

discussion of this topic can be found.

Electron emitters

There

are three active electron emission technologies usually considered for

EDT applications: hollow cathode plasma contactors (HCPCs), thermionic cathodes

(TCs), and field emitter arrays (FEAs). System level configurations

will be presented for each device, as well as the relative costs,

benefits, and validation.

Thermionic cathode (TC)

Thermionic emission

is the flow of electrons from a heated charged metal or metal oxide

surface, caused by thermal vibrational energy overcoming the work function

(electrostatic forces holding electrons to the surface). The

thermionic emission current density, J, rises rapidly with increasing

temperature, releasing a significant number of electrons into the vacuum

near the surface. The quantitative relation is given in the equation

This equation is called the Richardson-Dushman or Richardson equation. (ф is approximately 4.54 eV and AR ~120 A/cm2 for tungsten).

Once the electrons are thermionically emitted from the TC surface

they require an acceleration potential to cross a gap, or in this case,

the plasma sheath. Electrons can attain this necessary energy to

escape the SCL of the plasma sheath if an accelerated grid, or electron

gun, is used. The equation

shows what potential is needed across the grid in order to emit a certain current entering the device.

Here, η is the electron gun assembly (EGA) efficiency (~0.97 in

TSS-1), ρ is the perveance of the EGA (7.2 micropervs in TSS-1), ΔVtc is the voltage across the accelerating grid of the EGA, and It is the emitted current.

The perveance defines the space charge limited current that can be

emitted from a device. The figure below displays commercial examples of

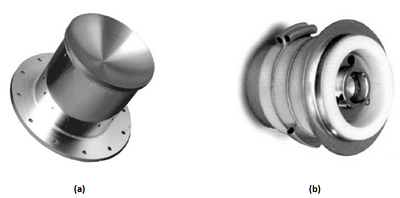

thermionic emitters and electron guns produced at Heatwave Labs Inc.

Example of an electron emitting a) Thermionic Emitter and an electron accelerating b) Electron Gun Assembly.

TC electron emission will occur in one of two different regimes:

temperature or space charge limited current flow. For temperature

limited flow every electron that obtains enough energy to escape from

the cathode surface is emitted, assuming the acceleration potential of

the electron gun is large enough. In this case, the emission current is

regulated by the thermionic emission process, given by the Richardson

Dushman equation. In SCL electron current flow there are so many

electrons emitted from the cathode that not all of them are accelerated

enough by the electron gun to escape the space charge. In this case,

the electron gun acceleration potential limits the emission current.

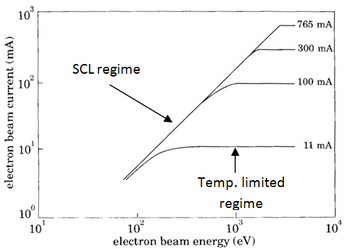

The below chart displays the temperature limiting currents and SCL

effects. As the beam energy of the electrons is increased, the total

escaping electrons can be seen to increase. The curves that become

horizontal are temperature limited cases.

Typical Electron Generator Assembly (EGA) current voltage characteristics as measured in a vacuum chamber.

Electron field emitter arrays (FEAs)

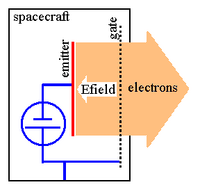

Field Emission

In field emission, electrons tunnel through a potential barrier,

rather than escaping over it as in thermionic emission or photoemission.

For a metal at low temperature, the process can be understood in terms

of the figure below. The metal can be considered a potential box, filled

with electrons to the Fermi level (which lies below the vacuum level by

several electron volts). The vacuum level represents the potential

energy of an electron at rest outside the metal in the absence of an

external field. In the presence of a strong electric field, the

potential outside the metal will be deformed along the line AB, so that a

triangular barrier is formed, through which electrons can tunnel.

Electrons are extracted from the conduction band with a current density

given by the Fowler−Nordheim equation

Energy level scheme for field emission from a metal at absolute zero temperature.

AFN and BFN are the constants determined by measurements of the FEA

with units of A/V2 and V/m, respectively. EFN is the electric field

that exists between the electron emissive tip and the positively biased

structure drawing the electrons out. Typical constants for Spindt type

cathodes include: AFN = 3.14 x 10-8 A/V2 and BFN = 771 V/m. (Stanford

Research Institute data sheet). An accelerating structure is typically

placed in close proximity with the emitting material as in the below

figure. Close (micrometer

scale) proximity between the emitter and gate, combined with natural or

artificial focusing structures, efficiently provide the high field

strengths required for emission with relatively low applied voltage and

power. The following figure below displays close up visual images of a

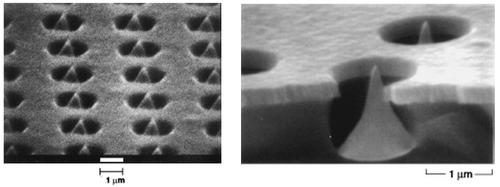

Spindt emitter.

Magnified

pictures of a field emitter array (SEM photograph of an SRI Ring

Cathode developed for the ARPA/NRL/NASA Vacuum Microelectronics

Initiative by Capp Spindt)

A variety of materials have been developed for field emitter arrays,

ranging from silicon to semiconductor fabricated molybdenum tips with

integrated gates to a plate of randomly distributed carbon nanotubes

with a separate gate structure suspended above. The advantages of field emission technologies over alternative electron emission methods are:

- No requirement for a consumable (gas) and no resulting safety considerations for handling a pressurized vessel

- A low-power capability

- Having moderate power impacts due to space-charge limits in the emission of the electrons into the surrounding plasma.

One major issue to consider for field emitters is the effect of

contamination. In order to achieve electron emission at low voltages,

field emitter array tips are built on a micrometer-level scale sizes.

Their performance depends on the precise construction of these small

structures. They are also dependent on being constructed with a material

possessing a low work-function. These factors can render the device

extremely sensitive to contamination, especially from hydrocarbons and

other large, easily polymerized molecules.

Techniques for avoiding, eliminating, or operating in the presence of

contaminations in ground testing and ionospheric (e.g. spacecraft

outgassing) environments are critical. Research at the University of

Michigan and elsewhere has focused on this outgassing issue. Protective

enclosures, electron cleaning, robust coatings, and other design

features are being developed as potential solutions.

FEAs used for space applications still require the demonstration of

long term stability, repeatability, and reliability of operation at gate

potentials appropriate to the space applications.

Hollow cathode

Hollow cathodes

emit a dense cloud of plasma by first ionizing a gas. This creates a

high density plasma plume which makes contact with the surrounding

plasma. The region between the high density plume and the surrounding

plasma is termed a double sheath or double layer. This double layer is

essentially two adjacent layers of charge. The first layer is a

positive layer at the edge of the high potential plasma (the contactor

plasma cloud). The second layer is a negative layer at the edge of the

low potential plasma (the ambient plasma). Further investigation of the

double layer phenomenon has been conducted by several people.

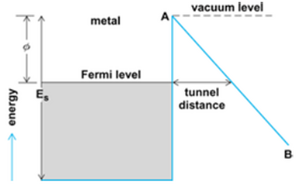

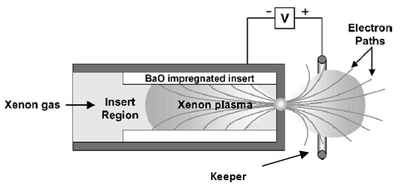

One type of hollow cathode consists of a metal tube lined with a

sintered barium oxide impregnated tungsten insert, capped at one end by a

plate with a small orifice, as shown in the below figure.

Electrons are emitted from the barium oxide impregnated insert by

thermionic emission. A noble gas flows into the insert region of the HC

and is partially ionized by the emitted electrons that are accelerated

by an electric field near the orifice (Xenon is a common gas used for

HCs as it has a low specific ionization energy (ionization potential per

unit mass). For EDT purposes, a lower mass would be more beneficial

because the total system mass would be less. This gas is just used for

charge exchange and not propulsion.). Many of the ionized xenon atoms

are accelerated into the walls where their energy maintains the

thermionic emission temperature. The ionized xenon also exits out of the

orifice. Electrons are accelerated from the insert region, through the

orifice to the keeper, which is always at a more positive bias.

Schematic of a Hollow Cathode System.

In electron emission mode, the ambient plasma is positively biased

with respect to the keeper. In the contactor plasma, the electron

density is approximately equal to the ion density. The higher energy

electrons stream through the slowly expanding ion cloud, while the lower

energy electrons are trapped within the cloud by the keeper potential.

The high electron velocities lead to electron currents much greater

than xenon ion currents. Below the electron emission saturation limit

the contactor acts as a bipolar emissive probe. Each outgoing ion

generated by an electron allows a number of electrons to be emitted.

This number is approximately equal to the square root of the ratio of

the ion mass to the electron mass.

It can be seen in the below chart what a typical I-V curve looks

like for a hollow cathode in electron emission mode. Given a certain

keeper geometry (the ring in the figure above that the electrons exit

through), ion flow rate, and Vp, the I-V profile can be determined.

Typical I-V Characteristic curve for a Hollow Cathode.

The operation of the HC in the electron collection mode is called the

plasma contacting (or ignited) operating mode. The “ignited mode” is

so termed because it indicates that multi-ampere current levels can be

achieved by using the voltage drop at the plasma contactor. This

accelerates space plasma electrons which ionize neutral expellant flow

from the contactor. If electron collection currents are high and/or

ambient electron densities are low, the sheath at which electron current

collection is sustained simply expands or shrinks until the required

current is collected.

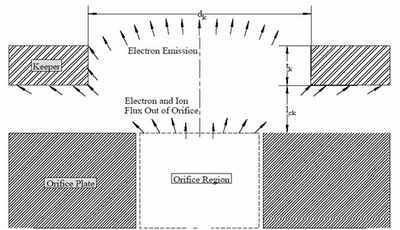

In addition, the geometry affects the emission of the plasma from

the HC as seen in the below figure. Here it can be seen that,

depending on the diameter and thickness of the keeper and the distance

of it with respect to the orifice, the total emission percentage can be

affected.

Typical Schematic detailing the HC emission geometry.

Plasma collection and emission summary

All

of the electron emission and collection techniques can be summarized in

the table following. For each method there is a description as to

whether the electrons or ions in the system increased or decreased based

on the potential of the spacecraft with respect to the plasma.

Electrons (e-) and ions (ions+) indicates that the number of electrons

or ions are being increased (↑) or reduced (↓). Also, for each method

some special conditions apply (see the respective sections in this

article for further clarification of when and where it applies).

Passive e− and ion emission/collection V − Vp < 0 V − Vp > 0 Bare tether: OML ions+ ↑ e− ↑ Ram collection ions+ ↑ 0 Thermal collection ions+ ↑ e− ↑ Photoemmision e− ↓ e− ↓,~0 Secondary electron emission e− ↓ e− ↓ Secondary ion emission ions+ ↓,~0 0 Retardation regieme e− ↑ ions+ ↑, ~0 Active e− and ion emission Potential does not matter Thermionic emission e− ↓ Field emitter arrays e− ↓ Hollow cathodes e− ↓ e− ↑

For use in EDT system modeling, each of the passive electron

collection and emission theory models has been verified by reproducing

previously published equations and results. These plots include:

orbital motion limited theory, Ram collection, and thermal collection, photoemission, secondary electron emission, and secondary ion emission.

Electrodynamic tether system fundamentals

In

order to integrate all the most recent electron emitters, collectors,

and theory into a single model, the EDT system must first be defined and

derived. Once this is accomplished it will be possible to apply this

theory toward determining optimizations of system attributes.

There are a number of derivations that solve for the potentials and currents involved in an EDT system numerically.

The derivation and numerical methodology of a full EDT system that

includes a bare tether section, insulating conducting tether, electron

(and ion) endbody emitters, and passive electron collection is

described. This is followed by the simplified, all insulated tether

model. Special EDT phenomena and verification of the EDT system model

using experimental mission data will then be discussed.

Bare tether system derivation

An

important note concerning an EDT derivation pertains to the celestial

body which the tether system orbits. For practicality, Earth will be

used as the body that is orbited; however, this theory applies to any

celestial body with an ionosphere and a magnetic field.

The coordinates are the first thing that must be identified. For the purposes of this derivation, the x- and y-axis are defined as the east-west, and north-south directions with respect to the Earth's surface, respectively. The z-axis is defined as up-down from the Earth's center, as seen in the figure below. The parameters – magnetic field B, tether length L, and the orbital velocity vorb – are vectors that can be expressed in terms of this coordinate system, as in the following equations:

- (the magnetic field vector),

- (the tether position vector), and

- (the orbital velocity vector).

The components of the magnetic field can be obtained directly from the International Geomagnetic Reference Field

(IGRF) model. This model is compiled from a collaborative effort

between magnetic field modelers and the institutes involved in

collecting and disseminating magnetic field data from satellites and

from observatories and surveys around the world. For this derivation,

it is assumed that the magnetic field lines are all the same angle

throughout the length of the tether, and that the tether is rigid.

Orbit velocity vector

Realistically, the transverse electrodynamic forces cause the tether

to bow and to swing away from the local vertical. Gravity gradient

forces then produce a restoring force that pulls the tether back towards

the local vertical; however, this results in a pendulum-like motion

(Gravity gradient forces also result in pendulus motions without ED

forces). The B direction changes as the tether orbits the Earth, and

thus the direction and magnitude of the ED forces also change. This

pendulum motion can develop into complex librations in both the in-plane

and out-of-plane directions. Then, due to coupling between the

in-plane motion and longitudinal elastic oscillations, as well as

coupling between in-plane and out-of-plane motions, an electrodynamic

tether operated at a constant current can continually add energy to the

libration motions. This effect then has a chance to cause the libration

amplitudes to grow and eventually cause wild oscillations, including

one such as the 'skip-rope effect',

but that is beyond the scope of this derivation. In a non-rotating EDT

system (A rotating system, called Momentum Exchange Electrodynamic

Reboost [MXER]), the tether is predominantly in the z-direction due to

the natural gravity gradient alignment with the Earth.

Derivations

The

following derivation will describe the exact solution to the system

accounting for all vector quantities involved, and then a second

solution with the nominal condition where the magnetic field, the

orbital velocity, and the tether orientation are all perpendicular to

one another. The final solution of the nominal case is solved for in

terms of just the electron density, n_e, the tether resistance per unit

length, R_t, and the power of the high voltage power supply, P_hvps.

The below figure describes a typical EDT system in a series bias

grounded gate configuration (further description of the various types of

configurations analyzed have been presented)

with a blow-up of an infinitesimal section of bare tether. This figure

is symmetrically set up so either end can be used as the anode. This

tether system is symmetrical because rotating tether systems will need

to use both ends as anodes and cathodes at some point in its rotation.

The V_hvps will only be used in the cathode end of the EDT system, and

is turned off otherwise.

(a)

A circuit diagram of a bare tether segment with (b) an equivalent EDT

system circuit model showing the series bias grounded gate

configuration.

In-plane and out-of-plane direction is determined by the orbital

velocity vector of the system. An in-plane force is in the direction of

travel. It will add or remove energy to the orbit, thereby increasing

the altitude by changing the orbit into an elliptical one. An

out-of-plane force is in the direction perpendicular to the plane of

travel, which causes a change in inclination. This will be explained in

the following section.

To calculate the in-plane and out-of-plane directions, the

components of the velocity and magnetic field vectors must be obtained

and the force values calculated. The component of the force in the

direction of travel will serve to enhance the orbit raising

capabilities, while the out-of-plane component of thrust will alter the

inclination. In the below figure, the magnetic field vector is solely

in the north (or y-axis) direction, and the resulting forces on an

orbit, with some inclination, can be seen. An orbit with no inclination

would have all the thrust in the in-plane direction.

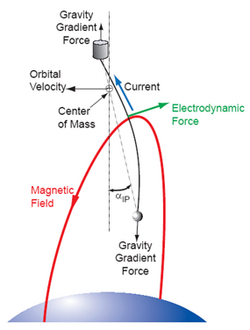

Description

of an in-plane

and out-of-plane

force.

|

Drag effects on an Electrodynamic Tether system.

|

There has been work conducted to stabilize the librations of the

tether system to prevent misalignment of the tether with the gravity

gradient. The below figure displays the drag effects an EDT system will

encounter for a typical orbit. The in-plane angle, α_ip, and

out-of-plane angle, α_op, can be reduced by increasing the endmass of

the system, or by employing feedback technology. Any deviations in the gravity alignment must be understood, and accounted for in the system design.

Interstellar travel

An application of the EDT system has been considered and researched

for interstellar travel by using the local interstellar medium of the Local Bubble.

It has been found to be feasible to use the EDT system to supply

on-board power given a crew of 50 with a requirement of 12 kilowatts per

person. Energy generation is achieved at the expense of kinetic energy

of the spacecraft. In reverse the EDT system could be used for

acceleration. However, this has been found to be ineffective. Thrustless

turning using the EDT system is possible to allow for course correction

and rendezvous in interstellar space. It will not, however, allow rapid

thrustless circling to allow a starship to re-enter a power beam or

make numerous solar passes due to an extremely large turning radius of

3.7*1016 km (~3.7 lightyears).

![\Delta V_{{tc}}=\left[{\frac {\eta \cdot I_{t}}{\rho }}\right]^{{2/3}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/931b24458ba4aeea5700e8321ee49da84aa2315d)