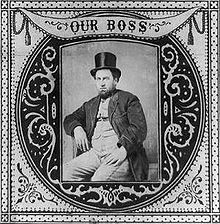

In this 1889 Udo Keppler cartoon from Puck, all of New York City politics revolves around boss Richard Croker.

A political machine is a political group in which an

authoritative boss or small group commands the support of a corps of

supporters and businesses (usually campaign workers), who receive rewards for their efforts. The machine's power is based on the ability of the boss or group to get out the vote for their candidates on election day.

Although these elements are common to most political parties and

organizations, they are essential to political machines, which rely on

hierarchy and rewards for political power, often enforced by a strong party whip structure. Machines sometimes have a political boss, often rely on patronage, the spoils system, "behind-the-scenes" control, and longstanding political ties within the structure of a representative democracy.

Machines typically are organized on a permanent basis instead of a

single election or event. The term may have a pejorative sense referring

to corrupt political machines.

The term "political machine" dates back to the 20th century in

the United States, where such organizations have existed in some

municipalities and states since the 18th century. Similar machines have

been described in Latin America, where the system has been called clientelism or political clientelism (after the similar Clientela relationship in the Roman Republic),

especially in rural areas, and also in some African states and other

emerging democracies, like postcommunist Eastern European countries. The

Swedish Social Democrats have also been referred, to a certain extent,

as a "political machine", thanks to its strong presence in "popular

houses".

Definition

The Encyclopædia Britannica defines "political machine" as, "in U.S. politics, a party organization, headed by a single boss

or small autocratic group, that commands enough votes to maintain

political and administrative control of a city, county, or state". William Safire, in his Safire's Political Dictionary,

defines "machine politics" as "the election of officials and the

passage of legislation through the power of an organization created for

political action". He notes that the term is generally considered pejorative, often implying corruption.

Hierarchy and discipline are hallmarks of political machines. "It generally means strict organization", according to Safire. Quoting Edward Flynn, a Bronx County Democratic leader who ran the borough from 1922 until his death in 1953,

he wrote "[...] the so-called 'independent' voter is foolish to assume

that a political machine is run solely on good will, or patronage. For

it is not only a machine; it is an army. And in any organization as in

any army, there must be discipline."

Political patronage, while often associated with political machines, is not essential to the definition for either Safire or Britannica.

Function

A

political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by

the use of tangible incentives—money, political jobs—and that is

characterized by a high degree of leadership control over member

activity.

Political machines started as grass roots organizations to gain the patronage

needed to win the modern election. Having strong patronage, these

"clubs" were the main driving force in gaining and getting out the

"straight party vote" in the election districts.

In the United States

1869 tobacco label featuring William M. Tweed, 19th-century political boss of New York City

In the late 19th century, large cities in the United States—Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Kansas City, New York City, Philadelphia, St. Louis—were accused of using political machines. During this time "cities experienced rapid growth under inefficient government". Each city's machine lived under a hierarchical system with a "boss" who held the allegiance of local business leaders, elected officials

and their appointees, and who knew the proverbial buttons to push to

get things done. Benefits and problems both resulted from the rule of

political machines.

This system of political control—known as "bossism"—emerged particularly in the Gilded Age.

A single powerful figure (the boss) was at the center and was bound

together to a complex organization of lesser figures (the political

machine) by reciprocity in promoting financial and social self-interest.

One of the most infamous of these political machines was Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party machine that played a major role in controlling New York City

and New York politics and helping immigrants, most notably the Irish,

rise up in American politics from the 1790s to the 1960s. From 1872,

Tammany had an Irish "boss". However, Tammany Hall also served as an

engine for graft and political corruption, perhaps most notoriously under William M. "Boss" Tweed

in the mid-19th century. Other historians note that Tammany Hall,

although widely known, was probably not the most wicked, instead

referring to the Republican party machine in Philadelphia.

Lord Bryce describes these political bosses saying:

An army led by a council seldom conquers: It must have a commander-in-chief, who settles disputes, decides in emergencies, inspires fear or attachment. The head of the Ring is such a commander. He dispenses places, rewards the loyal, punishes the mutinous, concocts schemes, negotiates treaties. He generally avoids publicity, preferring the substance to the pomp of power, and is all the more dangerous because he sits, like a spider, hidden in the midst of his web. He is a Boss.

When asked if he was a boss, James Pendergast said simply,

I've been called a boss. All there is to it is having friends, doing things for people, and then later on they'll do things for you... You can't coerce people into doing things for you—you can't make them vote for you. I never coerced anybody in my life. Wherever you see a man bulldozing anybody he don't last long.

Theodore Roosevelt, before he became president in 1901, was deeply involved in New York City politics. He explains how the machine worked:

The organization of a party in our city is really much like that of an army. There is one great central boss, assisted by some trusted and able lieutenants; these communicate with the different district bosses, whom they alternately bully and assist. The district boss in turn has a number of half-subordinates, half-allies, under him; these latter choose the captains of the election districts, etc., and come into contact with the common heelers.

Voting strategy

Many

machines formed in cities to serve immigrants to the U.S. in the late

19th century who viewed machines as a vehicle for political enfranchisement.

Machine workers helped win elections by turning out large numbers of

voters on election day. It was in the machine's interests to only

maintain a minimally winning amount of support. Once they were in the

majority and could count on a win, there was less need to recruit new

members, as this only meant a thinner spread of the patronage rewards to

be spread among the party members. As such, later-arriving immigrants,

such as Jews, Italians, and other immigrants from Southern and Eastern

Europe between the 1880s and 1910s, saw fewer rewards from the machine

system than the well-established Irish.

At the same time, the machines' staunchest opponents were members of

the middle class, who were shocked at the malfeasance and did not need

the financial help.

The corruption of urban politics in the United States

was denounced by private citizens. They achieved national and state

civil-service reform and worked to replace local patronage systems with civil service. By Theodore Roosevelt's time, the Progressive Era mobilized millions of private citizens to vote against the machines.

In the 1930s, James A. Farley was the chief dispenser of the Democratic Party's patronage system through the Post Office and the Works Progress Administration which eventually nationalized many of the job benefits machines provided. The New Deal allowed machines to recruit for the WPA and Civilian Conservation Corps,

making Farley's machine the most powerful. All patronage was screened

through Farley, including presidential appointments. The New Deal

machine fell apart after he left the administration over the third term

in 1940. Those agencies were abolished in 1943 and the machines

suddenly lost much of their patronage. The formerly poor immigrants who

had benefited under Farley's national machine had become assimilated and

prosperous and no longer needed the informal or extralegal aides

provided by machines. In the 1940s most of the big city machines collapsed, with the exception of Chicago. A local political machine in Tennessee was forcibly removed in what was known as the 1946 Battle of Athens.

Smaller communities such as Parma, Ohio,

in the post–Cold War Era under Prosecutor Bill Mason's "Good Old Boys"

and especially communities in the Deep South, where small-town machine

politics are relatively common, also feature what might be classified as

political machines, although these organizations do not have the power

and influence of the larger boss networks listed in this article. For

example, the "Cracker Party" was a Democratic Party political machine

that dominated city politics in Augusta, Georgia, for over half of the 20th century.

Political machines also thrive on Native American reservations, where

the veil of sovereignty is used as a shield against federal and state

laws against the practice.

Evaluation

The

phrase is considered derogatory "because it suggests that the interest

of the organization are placed before those of the general public",

according to Safire. Machines are criticized as undemocratic and

inevitably encouraging corruption.

Since the 1960s, some historians have reevaluated political

machines, considering them corrupt but efficient. Machines were

undemocratic but responsive. They were also able to contain the spending

demands of special interests. In Mayors and Money, a comparison of municipal government in Chicago and New York, Ester R. Fuchs credited the Cook County Democratic Organization with giving Mayor Richard J. Daley the political power to deny labor union contracts that the city could not afford and to make the state government assume burdensome costs like welfare

and courts. Describing New York, Fuchs wrote, "New York got reform, but

it never got good government." At the same time, as Dennis R. Judd and

Todd Swanstrom suggest in City Politics that this view

accompanied the common belief that there were no viable alternatives.

They go on to point out that this is a falsehood, since there are

certainly examples of reform oriented, anti-machine leaders during this

time.

In his mid-2016 article "How American Politics Went Insane" in The Atlantic, Jonathan Rauch

argued that the political machines of the past had flaws but provided

better governance than the alternatives. He wrote that political

machines created positive incentives for politicians to work together

and compromise – as opposed to pursuing "naked self-interest" the whole

time.

Japan

Japan's Liberal Democratic Party is often cited as another political machine, maintaining power in suburban and rural areas through its control of farm bureaus and road construction agencies. In Japan, the word jiban (literally "base" or "foundation") is the word used for political machines.

Japanese political factional leaders are expected to distribute mochidai,

literally snack-money, meaning funds to help subordinates win

elections. For the annual end-year gift in 1989 Party Headquarters gave

$200,000 to every member of the Diet. Supporters ignore wrongdoing to

collect the benefits from the benefactor, such as money payments

distributed by politicians to voters in weddings, funerals, New year

parties among other events. Political ties are held together by

marriages between the families of elite politicians. Nisei,

second generation political families, have grown increasingly numerous

in Japanese politics, due to a combination of name-recognition, business

contacts and financial resources, and the role of personal political

machines.