A

sequence for a stationary-pulsed-stationary maneuver for a pulsed

thermal nuclear rocket. During the stationary mode (working at constant

nominal power), the fuel temperature is always constant (solid black

line), and the propellant is coming cold (blue dotted lines) heated in

the chamber and exhausted in the nozzle (red dotted line). When

amplification in thrust or specific impulse

is required, the nuclear core is "switched on" to a pulsed mode. In

this mode, the fuel in continuously quenched and instantaneously heated

by the pulses. Once the requirements for high thrust and specific

impulse are not required, the nuclear core is "switched on" to the

initial stationary mode.

A pulsed nuclear thermal rocket is a type of nuclear thermal rocket (NTR) concept developed at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia, Spain and presented at the 2016 AIAA/SAE/ASEE Propulsion Conference for thrust and specific impulse (Isp) amplification in a conventional nuclear thermal rocket.

The pulsed nuclear thermal rocket is a bimodal rocket able to

work in a stationary (at constant nominal power as in a conventional

NTR), and as well as a pulsed mode as a TRIGA-like reactor, making possible the production of high power and an intensive neutron flux

in short time intervals. In contrast to nuclear reactors where

velocities of the coolant are no larger than a few meter per second and

thus, typical residence time is on seconds, however, in rockets chambers with subsonic velocities of the propellant around hundreds of meters per second, residence time are around

to :

and then a long power pulse translates into an important gain in

energy in comparison with the stationary mode. The gained energy -by

pulsing the nuclear core, can be used for thrust amplification by increasing the propellant mass flow, or using the intensive neutron flux to produce a very high specific impulse amplification – even higher than the fission-fragment rocket, where in the pulsed rocket the final propellant temperature is only limited by the radiative cooling after the pulsation.

Statement of the concept

A

rough calculation for the energy gain by using a pulsed thermal nuclear

rocket in comparison with the conventional stationary mode, is as

follows.

The energy stored into the fuel after a pulsation, is the sensible heat stored because the fuel temperature increase. This energy may be written as

where:

- is the sensible heat stored after pulsation,

- is the fuel heat capacity,

- is the fuel mass,

- is the temperature increase between pulsations.

On the other hand, the energy generated in the stationary mode, i.e.,

when the nuclear core operates at nominal constant power is given by

where:

- is the linear power of the fuel (power per length of fuel),

- is the length of the fuel,

- is the residence time of the propellant in the chamber.

Also, for the case of cylindrical geometries for the nuclear fuel we have

and the linear power given by

Where:

- is the radius of the cylindrical fuel,

- the fuel density,

- the fuel thermal conductivity,

- is the fuel temperature at the center line,

- is the surface or cladding temperature.

Therefore, the energy ratio between the pulsed mode and the stationary mode, yields

Where the term inside the bracket, is the quenching rate.

Typical average values of the parameters for common nuclear fuels as MOX fuel or uranium dioxide are: heat capacities, thermal conductivity and densities around , and , respectively., with radius close to , and the temperature drop between the center line and the cladding on or less (which result in linear power on . With these values the gain in energy is approximately given by:

where is given in .

Because the residence time of the propellant in the chamber is on to

considering subsonic velocities of the propellant of hundreds of meters

per second and meter chambers, then, with temperatures differences on

or quenching rates on

energy amplification by pulsing the core could be thousands times

larger than the stationary mode. More rigorous calculations considering

the transient heat transfer theory shows energy gains around hundreds

or thousands times, i.e., .

Quenching rates on are typical in the technology for production of amorphous metal, where extremely rapid cooling in the order of are required.

Direct thrust amplification

The most direct way to harness the amplified energy by pulsing the nuclear core is by increasing the thrust via increasing the propellant mass flow.

Increasing the thrust

in the stationary mode -where power is fixed by thermodynamic

constraints, is only possible by sacrificing exhaust velocity. In fact,

the power is given by

where

is the propellant mass flow. Thus, if it is desired to increase the

thrust, say, n-times in the stationary mode, it will be necessary to

increase -times the propellant mass flow, and decreasing -times the exhaust velocity. However, if the nuclear core is pulsed, thrust may be amplified -times by amplifying the power -times and the propellant mass flow -times and keeping constant the exhaust velocity.

Isp amplification

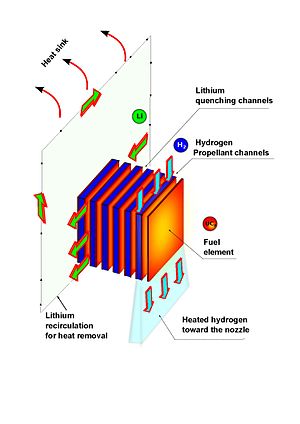

Pulsed nuclear thermal rocket unit cell concept for Isp

amplification. In this cell, hydrogen-propellant is heated by the

continuous intense neutronic pulses in the propellant channels. At the

same time, the unwanted energy from the fission fragments is removed by a

solidary cooling channel with lithium or other liquid metal.

The attainment of high exhaust velocity or specific impulse (Isp) is the first concern. The most general expression for the Isp is given by

being a constant, and

the temperature of the propellant before expansion. However, the

temperature of the propellant is related directly with the energy as , where is the Boltzmann constant. Thus,

being a constant.

In a conventional stationary NTR, the energy

for heating the propellant is almost from the fission fragments which

encompass almost the 95% of the total energy, and the faction of energy

from prompt neutrons

is only around 5%, and therefore, in comparison, is almost negligible.

However, if the nuclear core is pulsed -as previously discussed, it is

able to produce times more energy than the stationary mode, and then the fraction of prompt neutrons or

could be equal or larger than the total energy in the stationary mode;

and because this neutron energy is directly transported from the fuel

into the propellant as kinetic energy

-unlike the energy from fission fragments which is transported as heat

from the fuel into the propellant, then is not constrained by the second

law of thermodynamics, meaning that there is no impediment to

transport this energy from the fuel to the propellant even if the fuel

is colder than the propellant, in other words, it is possible a "

propellant hotter than the fuel" which is the very limit for specific

impulse enhancement in classics NTRs.

In summary, if the pulse generates times more energy than the stationary mode, the Isp amplification is given by

Where:

- is the amplified specific impulse,

- the specific impulse in the stationary mode,

- the fraction of prompt neutrons,

- the energy amplification by pulsing the nuclear core.

With values of between to and prompt neutron fractions around , the hypothetical amplification attainable makes the concept specially interesting for interplanetary spaceflight.

Advantages of the design

There

are several advantages relative to conventional stationary NTR designs.

Because the neutron energy is transported as kinetic energy from the

fuel into the propellant, then a propellant hotter than the fuel is

possible and therefore the is not limited to the maximum temperature permissible by the fuel, i.e., its melting temperature.

The other nuclear rocket concept which allows a propellant hotter than the fuel is the fission fragment rocket. Because it directly uses the fission fragments as propellant, it can also achieve a very high specific impulse.

Other considerations

For amplification, only the energy from prompt neutrons, and some prompt gamma energy, is used for this purpose. The rest of the energy, i.e., the almost

from fission fragments is unwanted energy and must be continuously

evacuated by a heat removal auxiliary system using a suitable coolant.

Liquid metals, and particularly lithium, can provide the fast

quenching rates required. One aspect to be considered is the large

amount of energy which must be evacuated as residual heat (almost 95% of

the total energy). This implies a large dedicated heat transfer

surface.

As regards to the mechanism for pulsing the core, the pulsed mode

can be produced using a variety of configurations depending on the

desired frequency of the pulsations. For instance, the use of standard

control rods in a single or banked configuration with motor driving

mechanism or the use of standard pneumatically operated pulsing

mechanisms are suitable for generating up to 10 pulses per minute. For the production of pulses at rates up to 50 pulsations per second, the use of rotating wheels introducing alternately neutron poison and fuel or neutron poison and non-neutron poison

can be considered. However, for pulsations ranking the thousands of

pulses per second (kHz), optical choppers or modern wheels employing

magnetic bearings allow to revolve at 10 kHz.

If even faster pulsations are desired it would be necessary to make use

of a new type of pulsing mechanism that does not involve mechanical

motion, for example, lasers (based in the 3He polarization) as early

proposed by Bowman, or proton and neutron beams. Frequencies on the order of 1 kHz to 10 kHz are likely choices.

![{\displaystyle N={\frac {c_{f}\rho _{f}R_{f}^{2}}{4\pi \kappa _{f}(T_{f}-T_{s})}}\left[{\frac {\Delta T}{t}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3cc3d8bbf17435ecd5e6540d895a7eed01df2912)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {\Delta T}{t}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/119993b06792cbcbe246fa3f85021215f3f07973)

![{\displaystyle N\simeq 6\times 10^{-3}\left[{\frac {\Delta T}{t}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e360c24bce94b60cd9ba403d5190c9ebcd7724e)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {\Delta T}{t}}\right]\simeq 10^{6}K/s}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9dc973fcec662916086461ca907280aa6fdc678d)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {\Delta T}{t}}\right]\geq 10^{6}K/s}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b40bbb3e2f4fd268d27fc6d8164108a7b8b50528)

![{\displaystyle 10^{6}K/s\leq \left[{\frac {\Delta T}{t}}\right]\leq 10^{7}K/s}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/180c982caf4ee51ab513d82012e1976c012e8aa0)