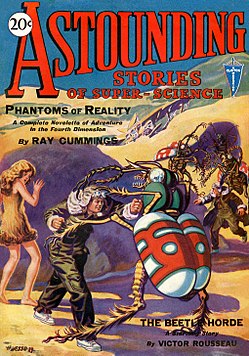

Title page of the first edition

| |

| Author | Friedrich Nietzsche |

|---|---|

| Original title | Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Publisher | Ernst Schmeitzner |

Publication date

| 1883–1885 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Preceded by | The Gay Science |

| Followed by | Beyond Good and Evil |

Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None (German: Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen, also translated as Thus Spake Zarathustra) is a philosophical novel by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, composed in four parts written and published between 1883 and 1885. Much of the work deals with ideas such as the "eternal recurrence of the same", the parable on the "death of God", and the "prophecy" of the Übermensch, which were first introduced in The Gay Science. Nietzsche himself considered Zarathustra to be his magnum opus.

Origins

Nietzsche wrote in Ecce Homo that the central idea of Zarathustra occurred to him by a "pyramidal block of stone" on the shores of Lake Silvaplana.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra was conceived while Nietzsche was writing The Gay Science; he made a small note, reading "6,000 feet beyond man and time", as evidence of this. More specifically, this note related to the concept of the eternal recurrence, which is, by Nietzsche's admission, the central idea of Zarathustra; this idea occurred to him by a "pyramidal block of stone" on the shores of Lake Silvaplana in the Upper Engadine,

a high alpine region whose valley floor is at 6,000 feet (1,800 m).

Nietzsche planned to write the book in three parts over several years.

He wrote that the ideas for Zarathustra first came to him while walking on two roads surrounding Rapallo, according to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche in the introduction of Thomas Common's early translation of the book.

Although Part Three was originally planned to be the end of the book, and ends with a strong climax,

Nietzsche subsequently decided to write an additional three parts;

ultimately, however, he composed only the fourth part, which is viewed

to constitute an intermezzo.

Nietzsche commented in Ecce Homo

that for the completion of each part: "Ten days sufficed; in no case,

neither for the first nor for the third and last, did I require more"

(trans. Kaufmann). The first three parts were first published

separately, and were subsequently published in a single volume in 1887.

The fourth part remained private after Nietzsche wrote it in 1885; a

scant forty copies were all that were printed, apart from seven others

that were distributed to Nietzsche's close friends. In March 1892, the

four parts were finally reprinted as a single volume. Since then, the

version most commonly produced has included all four parts.

The original text contains a great deal of word-play. An example of this is the use of words beginning über ("over" or "above") and unter

("down" or "below"), often paired to emphasise the contrast, which is

not always possible to bring out in translation, except by coinages. An

example is Untergang, literally "down-going" but used in German

to mean "setting" (as of the sun) but also "sinking", "demise",

"downfall" or "doom"; which Nietzsche pairs with its opposite Übergang (meaning "transition", literally "over-going"). Another example is Übermensch (overman or superman), discussed later in this article.

Synopsis

The book chronicles the fictitious travels and speeches of Zarathustra. Zarathustra's namesake was the founder of Zoroastrianism, usually known in English as Zoroaster (Avestan: 𐬰𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬚𐬎𐬱𐬙𐬭𐬀, Zaraθuštra). Nietzsche is clearly portraying a "new" or "different" Zarathustra, one who turns traditional morality on its head. He goes on to characterize "what the name of Zarathustra means in my mouth, the mouth of the first immoralist":

For what constitutes the tremendous historical uniqueness of that Persian is just the opposite of this. Zarathustra was the first to consider the fight of good and evil the very wheel in the machinery of things: the transposition of morality into the metaphysical realm, as a force, cause, and end in itself, is his work. [...] Zarathustra created this most calamitous error, morality; consequently, he must also be the first to recognize it. [...] His doctrine, and his alone, posits truthfulness as the highest virtue; this means the opposite of the cowardice of the "idealist” who flees from reality [...]—Am I understood?—The self-overcoming of morality, out of truthfulness; the self-overcoming of the moralist, into his opposite—into me—that is what the name of Zarathustra means in my mouth.

— Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, "Why I Am a Destiny", §3, trans. Walter Kaufmann

Zarathustra has a simple characterisation and plot,

narrated sporadically throughout the text. It possesses a unique

experimental style, one that is, for instance, evident in newly invented

"dithyrambs" narrated or sung by Zarathustra. Likewise, the separate Dionysian-Dithyrambs was written in autumn 1888, and printed with the full volume in 1892, as the corollaries of Zarathustra's "abundance".

Some speculate that Nietzsche intended to write about final acts

of creation and destruction brought about by Zarathustra. However, the

book lacks a finale to match that description; its actual ending

focuses more on Zarathustra recognizing that his legacy is beginning to

perpetuate, and consequently choosing to leave the higher men to their

own devices in carrying his legacy forth.

Zarathustra also contains the famous dictum "God is dead", which had appeared earlier in The Gay Science. In his autobiographical work Ecce Homo, Nietzsche

states that the book's underlying concept is discussed within "the

penultimate section of the fourth book" of 'The Gay Science' (Ecce Homo, Kaufmann). It is the eternal recurrence of the same events.

This concept first occurred to Nietzsche while he was walking in Switzerland through the woods along the lake of Silvaplana (close to Surlej); he was inspired by the sight of a gigantic, towering, pyramidal rock. Before Zarathustra, Nietzsche had mentioned the concept in the fourth book of The Gay Science (e.g., sect. 341); this was the first public proclamation of the notion by him. Apart from its salient presence in Zarathustra,

it is also echoed throughout Nietzsche's work. At any rate, it is by

Zarathustra's transfiguration that he embraces eternity, that he at last

ascertains "the supreme will to power". This inspiration finds its expression with Zarathustra's roundelay, featured twice in the book, once near the story's close:

O man, take care!

What does the deep midnight declare?

"I was asleep—

From a deep dream I woke and swear:—

The world is deep,

Deeper than day had been aware.

Deep is its woe—

Joy—deeper yet than agony:

Woe implores: Go!

But all joy wants eternity—

Wants deep, wants deep eternity."

Another singular feature of Zarathustra, first presented in the prologue, is the designation of human beings as a transition between apes and the "Übermensch" (in English, either the "overman" or "superman"; or, superhuman or overhuman. English translators Thomas Common and R. J. Hollingdale use superman, while Kaufmann uses overman, and Parkes uses overhuman. Martin has opted to leave the nearly universally understood term as Übermensch in his new translation). The Übermensch

is one of the many interconnecting, interdependent themes of the story,

and is represented through several different metaphors. Examples

include: the lightning that is portended by the silence and raindrops of

a travelling storm cloud; or the sun's rise and culmination at its

midday zenith; or a man traversing a rope stationed above an abyss,

moving away from his uncultivated animality and towards the Übermensch.

The symbol of the Übermensch also alludes to Nietzsche's

notions of "self-mastery", "self-cultivation", "self-direction", and

"self-overcoming". Expounding these concepts, Zarathustra declares:

"I teach you the overman. Man is something that shall be overcome. What have you done to overcome him?"

"All beings so far have created something beyond themselves; and do you want to be the ebb of this great flood and even go back to the beasts rather than overcome man? What is the ape to man? A laughingstock or a painful embarrassment. And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughingstock or a painful embarrassment. You have made your way from worm to man, and much in you is still worm. Once you were apes, and even now, too, man is more ape than any ape."

"Whoever is the wisest among you is also a mere conflict and cross between plant and ghost. But do I bid you become ghosts or plants?"

"Behold, I teach you the overman! The overman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the overman shall be the meaning of the earth! I beseech you, my brothers, remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of otherworldly hopes! Poison-mixers are they, whether they know it or not. Despisers of life are they, decaying and poisoned themselves, of whom the earth is weary: so let them go!"

— Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Prologue, §3, trans. Walter Kaufmann

The book embodies a number of innovative poetical and rhetorical

methods of expression. It serves as a parallel and supplement to the

various philosophical ideas present in Nietzsche's body of work. He has,

however, said that "among my writings my Zarathustra stands to my mind by itself" (Ecce Homo, Preface, sec. 4, Kaufmann). Emphasizing its centrality and its status as his magnum opus, Nietzsche stated that:

With [Thus Spoke Zarathustra] I have given mankind the greatest present that has ever been made to it so far. This book, with a voice bridging centuries, is not only the highest book there is, the book that is truly characterized by the air of the heights—the whole fact of man lies beneath it at a tremendous distance—it is also the deepest, born out of the innermost wealth of truth, an inexhaustible well to which no pail descends without coming up again filled with gold and goodness.

— Ecce Homo, Preface, §4, trans. Walter Kaufmann

Since many of the book's ideas are also present in his other works, Zarathustra is seen to have served as a precursor to his later philosophical thought. With the book, Nietzsche embraced a distinct aesthetic assiduity. He later reformulated many of his ideas in Beyond Good and Evil

and various other writings that he composed thereafter. He continued to

emphasize his philosophical concerns; generally, his intention was to

show an alternative to repressive moral codes and to avert "nihilism" in all of its varied forms.

Other aspects of Thus Spoke Zarathustra relate to Nietzsche's proposed "Transvaluation of All Values". This incomplete project began with The Antichrist.

Themes

While

Nietzsche injects myriad ideas into the book, a few recurring themes

stand out. The overman (Übermensch), a self-mastered individual who has

achieved his full power, is an almost omnipresent idea in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Man as a race is merely a bridge between animals and the overman.

The eternal recurrence,

found elsewhere in Nietzsche's writing, is also mentioned. "Eternal

recurrence" is the possibility that all events in one's life will happen

again and again, infinitely. The embrace of all of life's horrors and

pleasures alike shows a deference and acceptance of fate, or Amor Fati.

The love and acceptance of one's path in life is a defining

characteristic of the overman. Faced with the knowledge that he would

repeat every action that he has taken, an overman would be elated as he

has no regrets and loves life. Opting to change any decision or event

in one's life would indicate the presence of resentment or fear;

contradistinctly the overman is characterized by courage and a Dionysian

spirit.

The will to power

is the fundamental component of the human identity. Everything we do

is an expression of self-realization that can sometimes take a form of a

will to power. The will to power is a psychological analysis of all

human action and is accentuated by self-overcoming and self-enhancement.

Contrasted with living for procreation, pleasure, or happiness, the

will to power is the summary of all man's struggle against his

surrounding environment as well as his reason for living in

Many criticisms of Christianity can be found in Thus Spoke Zarathustra,

in particular Christian values of good and evil and its belief in an

afterlife. The basis for his critique of Christianity lies in the

perceived squandering of our earthly lives in pursuit of a perfect

afterlife, of which there is no evidence. This empiricist view (denial

of afterlife) is not fully examined in a rational argument in the text,

but taken as a simple fact in Nietzsche's aphoristic writing style.

Judeo-Christian values are more thoroughly examined in On the Genealogy of Morals as a product of what he calls "slave morality".

Style

Noteworthy

for its format, the book comprises a philosophical work of fiction whose

style often lightheartedly imitates that of the New Testament and of the Platonic dialogues, at times resembling pre-Socratic

works in tone and in its use of natural phenomena as rhetorical and

explanatory devices. It also features frequent references to the Western

literary and philosophical traditions, implicitly offering an

interpretation of these traditions and of their problems. Nietzsche

achieves all of this through the character of Zarathustra (referring to the traditional prophet of Zoroastrianism),

who makes speeches on philosophic topics as he moves along a loose

plotline marking his development and the reception of his ideas. This

characteristic (following the genre of the Bildungsroman)

can be seen as an inline commentary on Zarathustra's (and Nietzsche's)

philosophy. All this, along with the book's ambiguity and paradoxical

nature, has helped its eventual enthusiastic reception by the reading

public, but has frustrated academic attempts at analysis (as Nietzsche

may have intended). Thus Spoke Zarathustra remained unpopular as a topic for scholars (especially those in the Anglo-American analytic tradition)

until the second half of the twentieth century brought widespread

interest in Nietzsche and his unconventional style that does not

distinguish between philosophy and literature. It offers formulations of eternal recurrence, and Nietzsche for the first time speaks of the Übermensch: themes that would dominate his books from this point onwards.

The critic Harold Bloom criticized Thus Spoke Zarathustra in The Western Canon (1994), calling the book "a gorgeous disaster" and "unreadable". Other commentators have suggested that Nietzsche's style is intentionally ironic

for much of the book. This irony relates to an internal conflict of

Nietzsche's: he hated religious leaders but perceived himself as at

least somewhat akin to one.

Translations

- Alexander Tille, 1896

- Thomas Common, 1909

- Walter Kaufmann, 1954

- R. J. Hollingdale, 1961

- Thomas Wayne, 2003

- Clancy Martin, 2005

- Graham Parkes, 2005

- Adrian Del Caro, edited by Robert Pippin, 2006

The book Thus Spoke Zarathustra with pictures by Lena Hades in German and Russian

The first English translation of Zarathustra was published in 1896 by Alexander Tille.

Thomas Common published a translation in 1909 which was based on Alexander Tille's earlier attempt. Common wrote in the style of Shakespeare or the King James Version of the Bible. Common's poetic interpretation of the text, which renders the title Thus Spake Zarathustra, received wide acclaim for its lambent portrayal. Common reasoned that because the original German was written in a pseudo-Luther-Biblical style, a pseudo-King-James-Biblical style would be fitting in the English translation.

The Common translation remained widely accepted until more critical translations, titled Thus Spoke Zarathustra, were published by Walter Kaufmann in 1954, and R.J. Hollingdale in 1961,

which are considered to convey more accurately the German text than the

Common version. Kaufmann's introduction to his own translation included

a blistering critique of Common's version; he notes that in one

instance, Common has taken the German "most evil" and rendered it

"baddest", a particularly unfortunate error not merely for his having

coined the term "baddest", but also because Nietzsche dedicated a third

of The Genealogy of Morals to the difference between "bad" and "evil". This and other errors led Kaufmann to wonder whether Common "had little German and less English".

The translations of Kaufmann and Hollingdale render the text in a far

more familiar, less archaic, style of language, than that of Common.

Thomas Wayne, an English Professor at Edison State College in

Fort Myers, Florida, published a translation in 2003. The introduction

by Roger W. Phillips, Ph.D., says "Wayne's close reading of the original

text has exposed the deficiencies of earlier translations, preeminent

among them that of the highly esteemed Walter Kaufmann", and gives

several reasons.

Clancy Martin's 2005 translation opens with criticism and praise

for these three seminal translators, Common, Kaufmann and Hollingdale.

He notes that the German text available to Common was considerably

flawed, and that the German text from which Hollingdale and Kaufmann

worked was itself untrue to Nietzsche's own work in some ways. Martin

criticizes Kaufmann for changing punctuation, altering literal and

philosophical meanings, and dampening some of Nietzsche's more

controversial metaphors.[12]

Kaufmann's version, which has become the most widely available,

features a translator's note suggesting that Nietzsche's text would have

benefited from an editor; Martin suggests that Kaufmann "took it upon

himself to become his [Nietzsche's] editor".

Graham Parkes describes his own 2005 translation as trying "above all to convey the musicality of the text".

In 2006, Cambridge University Press published a translation by Adrian Del Caro, edited by Robert Pippin.

Musical and literary adaptations

The book inspired Richard Strauss to compose the tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra, which he designated "freely based on Friedrich Nietzsche".

Zarathustra's Roundelay is set as part of Gustav Mahler's Third Symphony (1895–6), originally under the title What Man Tells Me, or alternatively What the Night Tells Me (Of Man).

Frederick Delius based his major choral-orchestral work A Mass of Life (1904–5) on texts from Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The work ends with a setting of Zarathustra's roundelay which Delius had composed earlier, in 1898, as a separate work. Another setting of the roundelay is one of the songs of Lukas Foss's Time Cycle for soprano and orchestra (1959–60).

Carl Orff also composed a three-movement setting of part of Nietzsche's text as a teenager, but this work remains unpublished.

The short score of the third symphony by Arnold Bax

originally began with a quotation from Thus Spoke Zarathustra: ‘My

wisdom became pregnant on lonely mountains; upon barren stones she

brought forth her young’.

Latin American writer Giannina Braschi wrote the philosophical novel United States of Banana based on Thus Spoke Zarathustra; in it, Zarathustra and Hamlet philosophize about the liberty of modern man in a capitalist society and seek to liberate Puerto Rico from the United States. United States of Banana was adapted to a theater play by Juan Pablo Felix (2015) and into comic book by Swedish Cartoonist Joakim Lindengren (2017); both adaptions prominently featured Zarathustra.

Italian progressive rock band Museo Rosenbach released in 1973 the album Zarathustra, with lyrics referring to the book.

Also Sprach Zarathustra is referenced in the Xenosaga video game series, even making it into the title of Xenosaga Episode III: Also Sprach Zarathustra. The plot covers similar topics that Friedrich Nietzsche covers in his writings.

The English translation of part 2 chapter 7 "Tarantulas" have

been narrated by Jordan Peterson and musically toned by artist Akira the

Don.

The title of graphic novel "Silent was Zarathustra" by Nicolas Wild is a reference to Nietzsche's work.

There is also a film of parts I - III of the Kaufmann translation

of "Thus Spoke Zarathustra" by Ronald Gerard Smith, 1993, distributed

by Films for the Humanities and Sciences, 2012 - 2019.

Selected editions

- Thus Spake Zarathustra, translated by Alexander Tille, Macmillan, New York and London, 1896.

- Thus Spake Zarathustra, translated by Thomas Common, T.N. Foulis, Edinbugh and London, 1909.

- Also sprach Zarathustra, edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag (study edition of the standard German Nietzsche edition)

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by Walter Kaufmann, New York: Random House; reprinted in The Portable Nietzsche, New York: The Viking Press, 1954 and Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1976

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by R. J. Hollingdale, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1961

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by Graham Parkes, Oxford: Oxford World's Classics, 2005

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by Adrian del Caro and edited by Robert Pippin, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by Clancy Martin, Barnes and Noble: Barnes and Noble Books, 2005

- Also sprach Zarathustra, edited by Institut of Philosophy of Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 2004. Bilingual Edition (German and Russian) with 20 oil paintings of Lena Hades. ISBN 5-9540-0019-0

Commentaries

- Gustav Naumann 1899–1901 Zarathustra-Commentar, 4 volumes. Leipzig : Haessel; http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006124821.

- Higgins, Kathleen. 1987, rev. ed. 2010. Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- osho. 1987. "Zarathustra: A God That Can Dance". Discourse given at OSHO Commune international, Pune, India.

- Lampert, Laurence. 1989. Nietzsche's Teaching: An Interpretation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rosen, Stanley. 1995. The Mask of Enlightenment: Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

- Seung, T. K. 2005. Nietzsche's Epic of the Soul: Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Claus Zittel: Das ästhetische Kalkül von Friedrich Nietzsches 'Also sprach Zarathustra'. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8260-4649-0

Introductions

- Rüdiger Schmidt Nietzsche für Anfänger: Also sprach Zarathustra – Eine Lese-Einführung (introduction in German to the work)

Essay collections

- Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra: Before Sunrise, edited by James Luchte, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2008. ISBN 1-84706-221-0