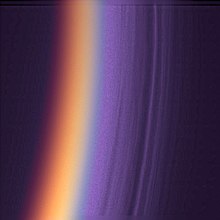

True-color image of layers of haze in Titan's atmosphere

| |

| General information | |

|---|---|

| Chemical species | Molar fraction |

| Composition | |

| Nitrogen | 94.2% |

| Methane | 5.65% |

| Hydrogen | 0.099% |

The atmosphere of Titan is the layer of gases surrounding Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. It is the only thick atmosphere of a natural satellite in the Solar System. Titan's lower atmosphere is primarily composed of nitrogen (94.2%), methane (5.65%), and hydrogen (0.099%). There are trace amounts of other hydrocarbons, such as ethane, diacetylene, methylacetylene, acetylene, propane, PAHs and of other gases, such as cyanoacetylene, hydrogen cyanide, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, cyanogen, acetonitrile, argon and helium. The isotopic study of nitrogen isotopes ratio also suggest acetonitrile may be present in quantities exceeding hydrogen cyanide and cyanoacetylene. The surface pressure is about 50% higher than Earth at 1.5 bars which is near the triple point of methane and allows there to be gaseous methane in the atmosphere and liquid methane on the surface. The orange color as seen from space is produced by other more complex chemicals in small quantities, possibly tholins, tar-like organic precipitates.

Observational history

The presence of a significant atmosphere was first suspected by Spanish astronomer Josep Comas i Solà, who observed distinct limb darkening on Titan in 1903, and confirmed by Gerard P. Kuiper in 1944 using a spectroscopic technique that yielded an estimate of an atmospheric partial pressure of methane of the order of 100 millibars (10 kPa).

Subsequent observations in the 1970s showed that Kuiper's figures had

been significant underestimates; methane abundances in Titan's

atmosphere were ten times higher, and the surface pressure was at least

double what he had predicted. The high surface pressure meant that

methane could only form a small fraction of Titan's atmosphere. In 1980, Voyager 1

made the first detailed observations of Titan's atmosphere, revealing

that its surface pressure was higher than Earth's, at 1.5 bars (about

1.48 times that of Earth's).

The joint NASA/ESA Cassini-Huygens

mission provided a wealth of information about Titan, and the Saturn

system in general, since entering orbit on July 1, 2004. It was

determined that Titan's atmospheric isotopic abundances were evidence

that the abundant nitrogen in the atmosphere came from materials in the Oort cloud, associated with comets, and not from the materials that formed Saturn in earlier times. It was determined that complex organic chemicals could arise on Titan, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, propylene, and methane.

The Dragonfly mission by NASA is planning to land a large aerial vehicle on Titan in 2034. The mission will study Titan's habitability and prebiotic chemistry at various locations. The drone-like aircraft will perform measurements of geologic processes, and surface and atmospheric composition.

Overview

Observations from the Voyager space probes have shown that the Titanean atmosphere is denser than Earth's, with a surface pressure about 1.48 times that of Earth's. Titan's atmosphere is about 1.19 times as massive as Earth's overall,

or about 7.3 times more massive on a per surface area basis. It

supports opaque haze layers that block most visible light from the Sun

and other sources and renders Titan's surface features obscure. The

atmosphere is so thick and the gravity so low that humans could fly

through it by flapping "wings" attached to their arms. Titan's lower gravity means that its atmosphere is far more extended than Earth's; even at a distance of 975 km, the Cassini spacecraft had to make adjustments to maintain a stable orbit against atmospheric drag. The atmosphere of Titan is opaque at many wavelengths and a complete reflectance spectrum of the surface is impossible to acquire from the outside. It was not until the arrival of Cassini–Huygens in 2004 that the first direct images of Titan's surface were obtained. The Huygens

probe was unable to detect the direction of the Sun during its descent,

and although it was able to take images from the surface, the Huygens team likened the process to "taking pictures of an asphalt parking lot at dusk".

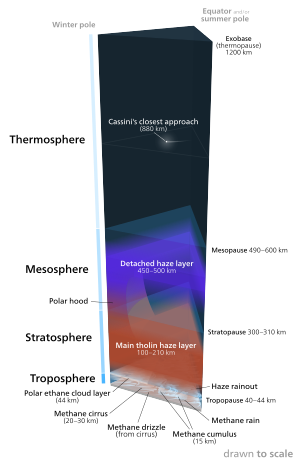

Vertical structure

Titan's vertical atmospheric structure is similar to Earth.

They both have a troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and

thermosphere. However, Titan's lower surface gravity creates a more

extended atmosphere, with scale heights of 15-50 km in comparison to 5-8 km on Earth. Voyager data, combined with data from Huygens and radiative-convective models provide increased understanding of Titan's atmospheric structure.

- Troposphere: This is the layer where a lot of the weather occurs on Titan. Since methane condenses out of Titan's atmosphere at high altitudes, its abundance increases below the tropopause at an altitude of 32 km, leveling off at a value of 4.9% between 8 km and the surface. Methane rain, haze rainout, and varying cloud layers are found in the troposphere.

- Stratosphere: The atmospheric composition in the stratosphere is 98.4% nitrogen—the only dense, nitrogen-rich atmosphere in the Solar System aside from Earth's—with the remaining 1.6% composed mostly of methane (1.4%) and hydrogen (0.1–0.2%). The main tholin haze layer lies in the stratosphere at about 100-210 km. In this layer of the atmosphere there is a strong temperature inversion caused by the haze due to a high ratio of shortwave to infrared opacity.

- Mesosphere: A detached haze layer is found at about 450-500 km, within the mesosphere. The temperature at this layer is similar to that of the thermosphere because of the cooling of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) lines.

- Thermosphere: Particle production begins in the thermosphere This was concluded after finding and measuring heavy ions and particles. This was also Cassini's closest approach in Titan's atmosphere.

- Ionosphere: Titan's ionosphere is also more complex than Earth's, with the main ionosphere at an altitude of 1,200 km but with an additional layer of charged particles at 63 km. This splits Titan's atmosphere to some extent into two separate radio-resonating chambers. The source of natural extremely-low-frequency (ELF) waves on Titan, as detected by Cassini–Huygens, is unclear as there does not appear to be extensive lightning activity.

Atmospheric composition and chemistry

Titan's

atmospheric chemistry is diverse and complex. Each layer of the

atmosphere has unique chemical interactions occurring within that are

then interacting with other sub layers in the atmosphere. For instance,

the hydrocarbons are thought to form in Titan's upper atmosphere in

reactions resulting from the breakup of methane by the Sun's ultraviolet light, producing a thick orange smog.

The table below highlights the production and loss mechanisms of the

most abundant photochemically produced molecules in Titan's atmosphere.

| Molecule | Production | Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | Methane photolysis | Escape |

| Carbon Monoxide | ||

| Ethane | Condensation | |

| Acetylene | Condensation | |

| Propane | Condensation | |

| Ethylene | ||

| Hydrogen Cyanide | Condensation | |

| Carbon Dioxide | Condensation | |

| Methylacetylene | ||

| Diacetylene |

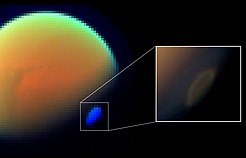

A cloud imaged in false color over Titan's north pole.

Magnetic field

Titan has no magnetic field,

although studies in 2008 showed that Titan retains remnants of Saturn's

magnetic field on the brief occasions when it passes outside Saturn's magnetosphere and is directly exposed to the solar wind. This may ionize and carry away some molecules from the top of the atmosphere. Titan's internal magnetic field is negligible, and perhaps even nonexistent. Its orbital distance of 20.3 Saturn radii does place it within Saturn's magnetosphere occasionally. However, the difference between Saturn's rotational period (10.7 hours) and Titan's orbital period (15.95 days) causes a relative speed of about 100 km/s between the Saturn's magnetized plasma and Titan. That can actually intensify reactions causing atmospheric loss, instead of guarding the atmosphere from the solar wind.

Chemistry of the ionosphere

In November 2007, scientists uncovered evidence of negative ions with

roughly 13 800 times the mass of hydrogen in Titan's ionosphere, which

are thought to fall into the lower regions to form the orange haze which

obscures Titan's surface. The smaller negative ions have been identified as linear carbon chain anions with larger molecules displaying evidence of more complex structures, possibly derived from benzene. These negative ions appear to play a key role in the formation of more complex molecules, which are thought to be tholins, and may form the basis for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, cyanopolyynes

and their derivatives. Remarkably, negative ions such as these have

previously been shown to enhance the production of larger organic

molecules in molecular clouds beyond our Solar System, a similarity which highlights the possible wider relevance of Titan's negative ions.

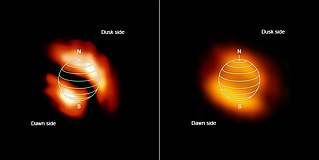

Titan's South Pole Vortex—a swirling HCN gas cloud (November 29, 2012).

Atmospheric circulation

There is a pattern of air circulation found flowing in the direction

of Titan's rotation, from west to east. In addition, seasonal variation

in the atmospheric circulation have also been detected. Observations by Cassini of the atmosphere made in 2004 also suggest that Titan is a "super rotator", like Venus, with an atmosphere that rotates much faster than its surface. The atmospheric circulation is explained by a big Hadley circulation that is occurring from pole to pole.

Methane cycle

Energy

from the Sun should have converted all traces of methane in Titan's

atmosphere into more complex hydrocarbons within 50 million years — a

short time compared to the age of the Solar System. This suggests that

methane must be somehow replenished by a reservoir on or within Titan

itself. Most of the methane on Titan is in the atmosphere. Methane is

transported through the cold trap at the tropopause.

Therefore the circulation of methane in the atmosphere influences the

radiation balance and chemistry of other layers in the atmosphere. If

there is a reservoir of methane on Titan, the cycle would only be stable

over geologic timescales.

Evidence that Titan's atmosphere contains over a thousand times more methane than carbon monoxide

would appear to rule out significant contributions from cometary

impacts, because comets are composed of more carbon monoxide than

methane. That Titan might have accreted an atmosphere from the early

Saturnian nebula at the time of formation also seems unlikely; in such a

case, it ought to have atmospheric abundances similar to the solar

nebula, including hydrogen and neon.

Many astronomers have suggested that the ultimate origin for the

methane in Titan's atmosphere is from within Titan itself, released via

eruptions from cryovolcanoes.

Daytime and Twilight (sunrise/sunset) Skies

Sky brightness models of a sunny day on Titan. The Sun is seen setting from noon until after dusk at 3 wavelengths: 5 μm, near-infrared (1-2 μm), and visible.

Each image shows a "rolled-out" version of the sky as seen from the

surface of Titan. The left side shows the Sun, while the right side

points away from the Sun. The top and bottom of the image are the zenith and the horizon respectively. The solar zenith angle represents the angle between the Sun and zenith (0°), where 90° is when the Sun reaches the horizon.

Sky brightness and viewing conditions are expected to be quite

different from Earth and Mars due to Titan's farther distance from the

Sun (~10 AU)

and complex haze layers in its atmosphere. The sky brightness model

videos show what a typical sunny day may look like standing on the

surface of Titan based on radiative transfer models.

For astronauts who see with visible light, the daytime sky has a distinctly dark orange color and appears uniform in all directions due to significant Mie scattering from the many high-altitude haze layers. The daytime sky is calculated to be ~100-1000 times dimmer than an afternoon on Earth, which is similar to the viewing conditions of a thick smog or dense fire smoke. The sunsets on Titan are expected to be "underwhelming events", where the Sun disappears about half-way up in the sky (~50° above the horizon)

with no distinct change in color. After that, the sky will slowly

darken until it reaches night. However, the surface is expected to

remain as bright as the full Moon up to 1 Earth day after sunset.

In near-infrared light, the sunsets resemble a Martian sunset or dusty desert sunset. Mie scattering

has a weaker influence at longer infrared wavelengths, allowing for

more colorful and variable sky conditions. During the daytime, the Sun

has a noticeable solar corona that transitions color from white to "red" over the afternoon. The afternoon sky brightness is ~100 times dimmer than Earth.

As evening time approaches, the Sun is expected to disappear fairly

close to the horizon. Titan's atmospheric optical depth is the lowest at

5 microns. So, the Sun at 5 microns may even be visible when it is below the horizon due to atmospheric refraction. Similar to images to Martian sunsets from Mars rovers, a fan-like corona is seen to develop above the Sun due to scattering from haze or dust at high-altitudes.

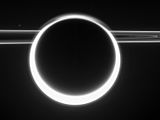

From outer space, Cassini images from near-infrared to UV wavelengths have shown that the twilight periods (sunrise/sunset) are brighter than the daytime on Titan. Scientists expect that planetary brightness will weaken going from the day to night side of the planetary body, known as the terminator. This paradoxical observation has not been observed on any other planetary body with a thick atmosphere.

The Titanean twilight outshining the dayside is likely due to a

combination of Titan's atmosphere extending hundreds of kilometers above

the surface and intense forward Mie scattering from the haze. Radiative transfer models have not reproduced this effect.

Atmospheric evolution

The persistence of a dense atmosphere on Titan has been enigmatic as the atmospheres of the structurally similar satellites of Jupiter, Ganymede and Callisto,

are negligible. Although the disparity is still poorly understood, data

from recent missions have provided basic constraints on the evolution

of Titan's atmosphere.

Layers of atmosphere, image from the Cassini spacecraft

Roughly speaking, at the distance of Saturn, solar insolation and solar wind flux are sufficiently low that elements and compounds that are volatile on the terrestrial planets tend to accumulate in all three phases. Titan's surface temperature is also quite low, about 94 K. Consequently, the mass fractions of substances that can become atmospheric constituents are much larger on Titan than on Earth. In fact, current interpretations suggest that only about 50% of Titan's mass is silicates, with the rest consisting primarily of various H2O (water) ices and NH3·H2O (ammonia hydrates). NH3, which may be the original source of Titan's atmospheric N2 (dinitrogen), may constitute as much as 8% of the NH3·H2O mass. Titan is most likely differentiated into layers, where the liquid water layer beneath ice Ih may be rich in NH3.

True-color image of layers of haze in Titan's atmosphere

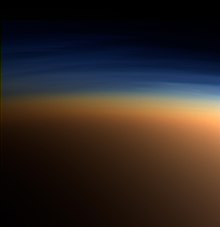

Titan's atmosphere backlit by the Sun, with Saturn's rings behind. An outer haze layer merges at top with the northern polar hood.

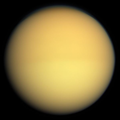

Titan's winter hemisphere (top) is slightly darker in visible light due to a high-altitude haze

Tentative constraints are available, with the current loss mostly due to low gravity and solar wind aided by photolysis. The loss of Titan's early atmosphere can be estimated with the 14N–15N isotopic ratio, because the lighter 14N is preferentially lost from the upper atmosphere under photolysis and heating. Because Titan's original 14N–15N ratio is poorly constrained, the early atmosphere may have had more N2 by factors ranging from 1.5 to 100 with certainty only in the lower factor. Because N2 is the primary component (98%) of Titan's atmosphere, the isotopic ratio suggests that much of the atmosphere has been lost over geologic time.

Nevertheless, atmospheric pressure on its surface remains nearly 1.5

times that of Earth as it began with a proportionally greater volatile

budget than Earth or Mars. It is possible that most of the atmospheric loss was within 50 million years of accretion, from a highly energetic escape of light atoms carrying away a large portion of the atmosphere (hydrodynamic escape). Such an event could be driven by heating and photolysis effects of the early Sun's higher output of X-ray and ultraviolet (XUV) photons.

Because Callisto and Ganymede

are structurally similar to Titan, it is unclear why their atmospheres

are insignificant relative to Titan's. Nevertheless, the origin of

Titan's N2 via geologically ancient photolysis of accreted and degassed NH3, as opposed to degassing of N2 from accretionary clathrates, may be the key to a correct inference. Had N2 been released from clathrates, 36Ar and 38Ar that are inert primordial isotopes of the Solar System should also be present in the atmosphere, but neither has been detected in significant quantities. The insignificant concentration of 36Ar and 38Ar also indicates that the ~40 K temperature required to trap them and N2 in clathrates did not exist in the Saturnian sub-nebula. Instead, the temperature may have been higher than 75 K, limiting even the accumulation of NH3 as hydrates.

Temperatures would have been even higher in the Jovian sub-nebula due

to the greater gravitational potential energy release, mass, and

proximity to the Sun, greatly reducing the NH3 inventory accreted by Callisto and Ganymede. The resulting N2 atmospheres may have been too thin to survive the atmospheric erosion effects that Titan has withstood.

An alternative explanation is that cometary impacts release more energy on Callisto and Ganymede than they do at Titan due to the higher gravitational field of Jupiter.

That could erode the atmospheres of Callisto and Ganymede, whereas the

cometary material would actually build Titan's atmosphere. However, the 2H–1H (i.e. D–H) ratio of Titan's atmosphere is (2.3±0.5)×10−4, nearly 1.5 times lower than that of comets. The difference suggests that cometary material is unlikely to be the major contributor to Titan's atmosphere. Titan's atmosphere also contains over a thousand times more methane than carbon monoxide

which supports the idea that cometary material is not a likely

contributor since comets are composed of more carbon monoxide than

methane.

Titan - three dust storms detected in 2009-2010.