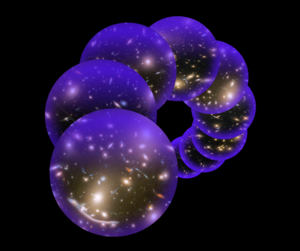

The UniverseMachine (also known as the Universe Machine) is a project of an ongoing series of astrophysical supercomputer simulations of various models of possible universes, that was created by astronomer Peter Behroozi and his research team at the Steward Observatory and the University of Arizona. As such, numerous universes with different physical characteristics may be simulated in order to develop insights into the possible beginning, and later evolution, of our current universe. One of the major objectives of the project is to better understand the role of dark matter in the development of the universe. According to Behroozi, "On the computer, we can create many different universes and compare them to the actual one, and that lets us infer which rules lead to the one we see."

Besides lead investigator Behroozi, research team members include astronomer Charlie Conroy of Harvard University, physicist Andrew Hearin of the Argonne National Laboratory and physicist Risa Wechsler of Stanford University. Support funding for the project is provided by NASA, the National Science Foundation and the Munich Institute for Astro- and Particle Physics.

Description

Besides using computers and related resources at the NASA Ames Research Center and the Leibniz-Rechenzentrum in Garching, Germany, the research team used the High-Performance Computing cluster at the University of Arizona. Two-thousand processors simultaneously processed the data over three weeks. In this way, the research team generated over 8 million universes, and at least 9.6×1013 galaxies. As such, the UniverseMachine program continuously produced millions of universes, each simulated universe containing 12 million galaxies, and each resulting simulated universe permitted to develop from 400 million years after the Big Bang, on up to the present day.

According to team member Wechsler, "The really cool thing about this study is that we can use all the data we have about galaxy evolution — the numbers of galaxies, how many stars they have and how they form those stars — and put that together into a comprehensive picture of the last 13 billion years of the universe." Wechsler further commented, "For me, the most exciting thing is that we now have a model where we can start to ask all of these questions in a framework that works ... We have a model that is inexpensive enough computationally, that we can essentially calculate an entire universe in about a second.Then we can afford to do that millions of times and explore all of the parameter space."

Results

One of the results of the study suggests that denser dark matter in the early universe didn't seem to negatively impact star formation rates as thought initially. According to the studies, galaxies of a given size were more likely to form stars much longer and at a high rate. The researchers expect to extend their studies with the project to include how often stars expire in supernovae, how dark matter may affect the shape of galaxies and eventually, by at least providing a better understanding of the workings of the universe, how life originated.