Genetically modified food controversies are disputes over the use of foods and other goods derived from genetically modified crops instead of conventional crops, and other uses of genetic engineering in food production. The disputes involve consumers, farmers, biotechnology companies, governmental regulators, non-governmental organizations, and scientists. The key areas of controversy related to genetically modified food (GM food or GMO food) are whether such food should be labeled, the role of government regulators, the objectivity of scientific research and publication, the effect of genetically modified crops on health and the environment, the effect on pesticide resistance, the impact of such crops for farmers, and the role of the crops in feeding the world population. In addition, products derived from GMO organisms play a role in the production of ethanol fuels and pharmaceuticals.

Specific concerns include mixing of genetically modified and non-genetically modified products in the food supply, effects of GMOs on the environment, the rigor of the regulatory process, and consolidation of control of the food supply in companies that make and sell GMOs. Advocacy groups such as the Center for Food Safety, Organic Consumers Association, Union of Concerned Scientists, and Greenpeace say risks have not been adequately identified and managed, and they have questioned the objectivity of regulatory authorities.

The safety assessment of genetically engineered food products by regulatory bodies starts with an evaluation of whether or not the food is substantially equivalent to non-genetically engineered counterparts that are already deemed fit for human consumption. No reports of ill effects have been documented in the human population from genetically modified food.

There is a scientific consensus that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food, but that each GM food needs to be tested on a case-by-case basis before introduction. Nonetheless, members of the public are much less likely than scientists to perceive GM foods as safe, although the concern is fast declining in the EU. The legal and regulatory status of GM foods varies by country, with some nations banning or restricting them and others permitting them with widely differing degrees of regulation.

Public perception

Consumer concerns about food quality first became prominent long before the advent of GM foods in the 1990s. Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle led to the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, the first major US legislation on the subject. This began an enduring concern over the purity and later "naturalness" of food that evolved from a single focus on sanitation to include others on added ingredients such as preservatives, flavors and sweeteners, residues such as pesticides, the rise of organic food as a category and, finally, concerns over GM food. Some consumers, including many in the US, came to see GM food as "unnatural", with various negative associations and fears (a reverse halo effect).

Specific perceptions include a view of genetic engineering as meddling with naturally evolved biological processes, and one that science has limitations on its comprehension of potential negative ramifications. An opposing perception is that genetic engineering is itself an evolution of traditional selective breeding, and that the weight of current evidence suggests current GM foods are identical to conventional foods in nutritional value and effects on health.

Surveys indicate widespread concern among consumers that eating genetically modified food is harmful, that biotechnology is risky, that more information is needed and that consumers need control over whether to take such risks. A diffuse sense that social and technological change is accelerating, and that people cannot affect this context of change, becomes focused when such changes affect food. Leaders in driving public perception of the harms of such food in the media include Jeffrey M. Smith, Dr. Oz, Oprah, and Bill Maher; organizations include Organic Consumers Association, Greenpeace (especially with regard to Golden rice) and Union of Concerned Scientists.

In the United States support or opposition or skepticism about GMO food is not divided by traditional partisan (liberal/conservative) lines, but young adults are more likely to have negative opinions on genetically modified food than older adults.

Religious groups have raised concerns over whether genetically modified food will remain kosher or halal. In 2001, no such foods had been designated as unacceptable by Orthodox rabbis or Muslim leaders.

Food writer Michael Pollan does not oppose eating genetically modified foods, but supports mandatory labeling of GM foods and has criticized the intensive farming enabled by certain GM crops, such as glyphosate-tolerant ("Roundup-ready") corn and soybeans. He has also expressed concerns about biotechnology companies holding the intellectual property of the foods people depend on, and about the effects of the growing corporatization of large-scale agriculture. To address these problems, Pollan has brought up the idea of open sourcing GM foods. The idea has since been adopted to varying degrees by companies like Syngenta, and is being promoted by organizations such as the New America Foundation. Some organizations, like The BioBricks Foundation, have already worked out open-source licenses that could prove useful in this endeavour.

Reviews and polls

An EMBO Reports article in 2003 reported that the Public Perceptions of Agricultural Biotechnologies in Europe project (PABE) found the public neither accepting nor rejecting GMOs. Instead, PABE found that public had "key questions" about GMOs: "Why do we need GMOs? Who benefits from their use? Who decided that they should be developed and how? Why were we not better informed about their use in our food, before their arrival on the market? Why are we not given an effective choice about whether or not to buy these products? Have potential long-term and irreversible consequences been seriously evaluated, and by whom? Do regulatory authorities have sufficient powers to effectively regulate large companies? Who wishes to develop these products? Can controls imposed by regulatory authorities be applied effectively? Who will be accountable in cases of unforeseen harm?" PABE also found that the public's scientific knowledge does not control public opinion, since scientific facts do not answer these questions. PABE also found that the public does not demand "zero risk" in GM food discussions and is "perfectly aware that their lives are full of risks that need to be counterbalanced against each other and against the potential benefits. Rather than zero risk, what they demanded was a more realistic assessment of risks by regulatory authorities and GMO producers."

In 2006, the Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology made public a review of U.S. survey results between 2001 and 2006. The review showed that Americans' knowledge of GM foods and animals was low throughout the period. Protests during this period against Calgene's Flavr Savr GM tomato mistakenly described it as containing fish genes, confusing it with DNA Plant Technology's fish tomato experimental transgenic organism, which was never commercialized.

A survey in 2007 by the Food Standards Australia New Zealand found that in Australia, where labeling is mandatory, 27% of Australians checked product labels to see whether GM ingredients were present when initially purchasing a food item.

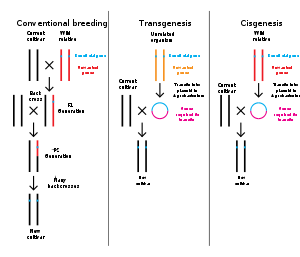

A review article about European consumer polls as of 2009 concluded that opposition to GMOs in Europe has been gradually decreasing, and that about 80% of respondents did not "actively avoid GM products when shopping". The 2010 "Eurobarometer" survey, which assesses public attitudes about biotech and the life sciences, found that cisgenics, GM crops made from plants that are crossable by conventional breeding, evokes a smaller reaction than transgenic methods, using genes from species that are taxonomically very different. Eurobrometer survey in 2019 reported that most Europeans do not care about GMO when the topic is not presented explicitly, and when presented only 27% choose it as a concern. In just nine years since identical survey in 2010 the level of concern has halved in 28 EU Member States. Concern about specific topics decreased even more, for example genome editing on its own only concerns 4%.

A Deloitte survey in 2010 found that 34% of U.S. consumers were very or extremely concerned about GM food, a 3% reduction from 2008. The same survey found gender differences: 10% of men were extremely concerned, compared with 16% of women, and 16% of women were unconcerned, compared with 27% of men.

A poll by The New York Times in 2013 showed that 93% of Americans wanted labeling of GM food.

The 2013 vote, rejecting Washington State's GM food labeling I-522 referendum came shortly after the 2013 World Food Prize was awarded to employees of Monsanto and Syngenta. The award has drawn criticism from opponents of genetically modified crops.

With respect to the question of "Whether GMO foods were safe to eat", the gap between the opinion of the public and that of American Association for the Advancement of Science scientists is very wide with 88% of AAAS scientists saying yes in contrast to 37% of the general public.

Public relations campaigns and protests

In May 2012, a group called "Take the Flour Back" led by Gerald Miles protested plans by a group from Rothamsted Experimental Station, based in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, to conduct an experimental trial wheat genetically modified to repel aphids. The researchers, led by John Pickett, wrote a letter to the group in early May 2012, asking them to call off their protest, aimed for 27 May 2012. Group member Lucy Harrap said that the group was concerned about spread of the crops into nature, and cited examples of outcomes in the United States and Canada. Rothamsted Research and Sense About Science ran question and answer sessions about such a potential.

The March Against Monsanto is an international grassroots movement and protest against Monsanto corporation, a producer of genetically modified organism (GMOs) and Roundup, a glyphosate-based herbicide. The movement was founded by Tami Canal in response to the failure of California Proposition 37, a ballot initiative which would have required labeling food products made from GMOs. Advocates support mandatory labeling laws for food made from GMOs .

The initial march took place on May 25, 2013. The number of protesters who took part is uncertain; figures of "hundreds of thousands" and the organizers' estimate of "two million" were variously cited. Events took place in between 330 and 436 cities around the world, mostly in the United States. Many protests occurred in Southern California, and some participants carried signs expressing support for mandatory labeling of GMOs that read "Label GMOs, It's Our Right to Know", and "Real Food 4 Real People". Canal said that the movement would continue its "anti-GMO cause" beyond the initial event. Further marches occurred in October 2013 and in May 2014 and 2015. The protests were reported by news outlets including ABC News, the Associated Press, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, USA Today, and CNN (in the United States), and The Guardian (outside the United States).

Monsanto said that it respected people's rights to express their opinion on the topic, but maintained that its seeds improved agriculture by helping farmers produce more from their land while conserving resources, such as water and energy. The company reiterated that genetically modified foods were safe and improved crop yields. Similar sentiments were expressed by the Hawaii Crop Improvement Association, of which Monsanto is a member.

In July 2013, the agricultural biotechnology industry launched a GMO transparency initiative called GMO Answers to address consumers’ questions about GM foods in the U.S. food supply. GMO Answers' resources included conventional and organic farmers, agribusiness experts, scientists, academics, medical doctors and nutritionists, and "company experts" from founding members of the Council for Biotechnology Information, which funds the initiative. Founding members include BASF, Bayer CropScience, Dow AgroSciences, DuPont, Monsanto Company and Syngenta.

In October 2013, a group called The European Network of Scientists for Social and Environmental Responsibility (ENSSER), posted a statement claiming that there is no scientific consensus on the safety of GMOs, which was signed by about 200 scientists in various fields in its first week. On January 25, 2015, their statement was formally published as a whitepaper by Environmental Sciences Europe.

Direct action

Earth Liberation Front, Greenpeace and others have disrupted GMO research around the world. Within the UK and other European countries, as of 2014 80 crop trials by academic or governmental research institutes had been destroyed by protesters. In some cases, threats and violence against people or property were carried out. In 1999, activists burned the biotech lab of Michigan State University, destroying the results of years of work and property worth $400,000.

In 1987, the ice-minus strain of P. syringae became the first genetically modified organism (GMO) to be released into the environment when a strawberry field in California was sprayed with the bacteria. This was followed by the spraying of a crop of potato seedlings. The plants in both test fields were uprooted by activist groups, but were re-planted the next day.

In 2011, Greenpeace paid reparations when its members broke into the premises of an Australian scientific research organization, CSIRO, and destroyed a genetically modified wheat plot. The sentencing judge accused Greenpeace of cynically using junior members to avoid risking their own freedom. The offenders were given 9-month suspended sentences.

On August 8, 2013 protesters uprooted an experimental plot of golden rice in the Philippines. British author, journalist, and environmental activist Mark Lynas reported in Slate that the vandalism was carried out by a group led by the extreme-left Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas or Peasant Movement of the Philippines (KMP), to the dismay of other protesters. Golden rice is designed prevent vitamin A deficiency which, according to Helen Keller International, blinds or kills hundreds of thousands of children annually in developing countries.

Response to anti-GMO sentiment

In 2017, two documentaries were released which countered the growing anti-GMO sentiment among the public. These included Food Evolution and Science Moms. Per the Science Moms director, the film "focuses on providing a science and evidence-based counter-narrative to the pseudoscience-based parenting narrative that has cropped up in recent years".

Conspiracy theories

There are various conspiracy theories related to the production and sale of genetically modified crops and genetically modified food that have been identified by some commentators such as Michael Shermer. Generally, these conspiracy theories posit that GMOs are being knowingly and maliciously introduced into the food supply either as a means to unduly enrich agribusinesses or as a means to poison or pacify the population.

A work seeking to explore risk perception over GMOs in Turkey identified a belief among the conservative political and religious figures who were opposed to GMOs that GMOs were "a conspiracy by Jewish Multinational Companies and Israel for world domination." Additionally, a Latvian study showed that a segment of the population believed that GMOs were part of a greater conspiracy theory to poison the population of the country.

Lawsuits

Foundation on Economic Trends v. Heckler

In 1983, environmental groups and protesters delayed the field tests of the genetically modified ice-minus strain of P. syringae with legal challenges.

Alliance for Bio-Integrity v. Shalala

In this case, the plaintiff argued both for mandatory labeling on the basis of consumer demand, and that GMO foods should undergo the same testing requirements as food additives because they are "materially changed" and have potentially unidentified health risks. The plaintiff also alleged that the FDA did not follow the Administrative Procedures Act in formulating and disseminating its policy on GMO's. The federal district court rejected all of those arguments and found that the FDA's determination that GMO's are Generally Recognized as Safe was neither arbitrary nor capricious. The court gave deference to the FDA's process on all issues, leaving future plaintiffs little legal recourse to challenge the FDA's policy on GMO's.

Diamond v. Chakrabarty

The Diamond v. Chakrabarty case was on the question of whether GMOs can be patented.

On 16 June 1980, the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 split decision, held that "A live, human-made micro-organism is patentable subject matter" under the meaning of U.S. patent law.

Scientific publishing

Scientific publishing on the safety and effects of GM foods is controversial.

Bt maize

One of the first incidents occurred in 1999, when Nature published a paper on potential toxic effects of Bt maize on butterflies. The paper produced a public uproar and demonstrations, however by 2001 multiple follow-up studies had concluded that "the most common types of Bt maize pollen are not toxic to monarch larvae in concentrations the insects would encounter in the fields" and that they had "brought that particular question to a close".

Concerned scientists began to patrol the scientific literature and react strongly, both publicly and privately, to discredit conclusions they view as flawed in order to prevent unjustified public outcry and regulatory action. A 2013 Scientific American article noted that a "tiny minority" of biologists have published concerns about GM food, and said that scientists who support the use of GMOs in food production are often overly dismissive of them.

Restrictive end-user agreements

Prior to 2010, scientists wishing to conduct research on commercial GM plants or seeds were unable to do so, because of restrictive end-user agreements. Cornell University's Elson Shields was the spokesperson for one group of scientists who opposed such restrictions. The group submitted a statement to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2009 protesting that "as a result of restrictive access, no truly independent research can be legally conducted on many critical questions regarding the technology".

A 2009 Scientific American editorial quoted a scientist who said that several studies that were initially approved by seed companies were blocked from publication when they returned "unflattering" results. While favoring protection of intellectual property rights, the editors called for the restrictions to be lifted and for the EPA to require, as a condition of approval, that independent researchers have unfettered access to genetically modified products for research.

In December 2009, the American Seed Trade Association agreed to "allow public researchers greater freedom to study the effects of GM food crops". The companies signed blanket agreements permitting such research. This agreement left many scientists optimistic about the future; other scientists still express concern as to whether this agreement has the ability to "alter what has been a research environment rife with obstruction and suspicion". Monsanto previously had research agreements (i.e., Academic Research Licenses) with approximately 100 universities that allowed for university scientists to conduct research on their GM products with no oversight.

Reviews

A 2011 analysis by Diels et al., reviewed 94 peer-reviewed studies pertaining to GMO safety to assess whether conflicts of interest correlated with outcomes that cast GMOs in a favorable light. They found that financial conflict of interest was not associated with study outcome (p = 0.631) while author affiliation to industry (i.e., a professional conflict of interest) was strongly associated with study outcome (p < 0.001). Of the 94 studies that were analyzed, 52% did not declare funding. 10% of the studies were categorized as "undetermined" with regard to professional conflict of interest. Of the 43 studies with financial or professional conflicts of interest, 28 studies were compositional studies. According to Marc Brazeau, an association between professional conflict of interest and positive study outcomes can be skewed because companies typically contract with independent researchers to perform follow-up studies only after in-house research uncovers favorable results. In-house research that uncovers negative or unfavorable results for a novel GMO is generally not further pursued.

A 2013 review, of 1,783 papers on genetically modified crops and food published between 2002 and 2012 found no plausible evidence of dangers from the use of then marketed GM crops. Biofortified, an independent nonprofit organization devoted to providing factual information and fostering discussion about agriculture, especially plant genetics and genetic engineering, planned to add the studies found by the Italian group to its database of studies about GM crops, GENERA.

In a 2014 review, Zdziarski et al. examined 21 published studies of the histopathology of GI tracts of rats that were fed diets derived from GM crops, and identified some systemic flaws in this area of the scientific literature. Most studies were performed years after the approval of the crop for human consumption. Papers were often imprecise in their descriptions of the histological results and the selection of study endpoints, and lacked necessary details about methods and results. The authors called for the development of better study guidelines for determining the long-term safety of eating GM foods.

A 2016 study by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that GM foods are safe for human consumption and they could find no conclusive evidence that they harm the environment nor wildlife. They analysed over 1.000 studies over the previous 30 years that GM crops have been available, reviewed 700 written presentations submitted by interested bodies and heard 80 witnesses. They concluded that GM crops had given farmers economic advantages but found no evidence that GM crops had increased yields. They also noted that weed resistance to GM crops could cause major agricultural problems but this could be addressed by better farming procedures.

Alleged data manipulation

A University of Naples investigation suggested that images in eight papers on animals were intentionally altered and/or misused. The leader of the research group, Federico Infascelli, rejected the claim. The research concluded that mother goats fed GM soybean meal secreted fragments of the foreign gene in their milk. In December 2015 one of the papers was retracted for "self-plagiarism", although the journal noted that the results remained valid. A second paper was retracted in March 2016 after The University of Naples concluded that "multiple heterogeneities were likely attributable to digital manipulation, raising serious doubts on the reliability of the findings".

Health

There is a scientific consensus that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food, but that each GM food needs to be tested on a case-by-case basis before introduction. Nonetheless, members of the public are much less likely than scientists to perceive GM foods as safe. The legal and regulatory status of GM foods varies by country, with some nations banning or restricting them, and others permitting them with widely differing degrees of regulation.

The ENTRANSFOOD project was a European Commission-funded scientist group chartered to set a research program to address public concerns about the safety and value of agricultural biotechnology. It concluded that "the combination of existing test methods provides a sound test-regime to assess the safety of GM crops." In 2010, the European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation reported that "The main conclusion to be drawn from the efforts of more than 130 research projects, covering a period of more than 25 years of involving more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than e.g. conventional plant breeding technologies."

Consensus among scientists and regulators pointed to the need for improved testing technologies and protocols. Transgenic and cisgenic organisms are treated similarly when assessed. However, in 2012 the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) GMO Panel said that "novel hazards" could be associated with transgenic strains. In a 2016 review, Domingo concluded that studies in recent years had established that GM soybeans, rice, corn, and wheat do not differ from the corresponding conventional crops in terms of short-term human health effects, but recommended that further studies of long-term effects be conducted.

Substantial equivalence

Most conventional agricultural products are the products of genetic manipulation via traditional cross-breeding and hybridization.

Governments manage the marketing and release of GM foods on a case-by-case basis. Countries differ in their risk assessments and regulations. Marked differences distinguish the US from Europe. Crops not intended as foods are generally not reviewed for food safety. GM foods are not tested in humans before marketing because they are not a single chemical, nor are they intended to be ingested using specific doses and intervals, which complicate clinical study design. Regulators examine the genetic modification, related protein products and any changes that those proteins make to the food.

Regulators check that GM foods are "substantially equivalent" to their conventional counterparts, to detect any negative unintended consequences. New protein(s) that differ from conventional food proteins or anomalies that arise in the substantial equivalence comparison require further toxicological analysis.

"The World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the British Royal Society, and every other respected organization that has examined the evidence has come to the same conclusion: consuming foods containing ingredients derived from GM crops is no riskier than consuming the same foods containing ingredients from crop plants modified by conventional plant improvement techniques."

In 1999, Andrew Chesson of the Rowett Research Institute warned that substantial equivalence testing "could be flawed in some cases" and that current safety tests could allow harmful substances to enter the human food supply. The same year Millstone, Brunner and Mayer argued that the standard was a pseudo-scientific product of politics and lobbying that was created to reassure consumers and aid biotechnology companies to reduce the time and cost of safety testing. They suggested that GM foods have extensive biological, toxicological and immunological tests and that substantial equivalence should be abandoned. This commentary was criticized for misrepresenting history, for distorting existing data and poor logic. Kuiper claimed that it oversimplified safety assessments and that equivalence testing involves more than chemical tests, possibly including toxicity testing. Keler and Lappe supported Congressional legislation to replace the substantial equivalence standard with safety studies. In a 2016 review, Domingo criticized the use of the "substantial equivalence" concept as a measure of the safety of GM crops.

Kuiper examined this process further in 2002, finding that substantial equivalence does not measure absolute risks, but instead identifies differences between new and existing products. He claimed that characterizing differences is properly a starting point for a safety assessment and "the concept of substantial equivalence is an adequate tool in order to identify safety issues related to genetically modified products that have a traditional counterpart". Kuiper noted practical difficulties in applying this standard, including the fact that traditional foods contain many toxic or carcinogenic chemicals and that existing diets were never proven to be safe. This lack of knowledge re conventional food means that modified foods may differ in anti-nutrients and natural toxins that have never been identified in the original plant, possibly allowing harmful changes to be missed. In turn, positive modifications may also be missed. For example, corn damaged by insects often contains high levels of fumonisins, carcinogenic toxins made by fungi that travel on insects' backs and that grow in the wounds of damaged corn. Studies show that most Bt corn has lower levels of fumonisins than conventional insect-damaged corn. Workshops and consultations organized by the OECD, WHO, and FAO have worked to acquire data and develop better understanding of conventional foods, for use in assessing GM foods.

A survey of publications comparing the intrinsic qualities of modified and conventional crop lines (examining genomes, proteomes and metabolomes) concluded that GM crops had less impact on gene expression or on protein and metabolite levels than the variability generated by conventional breeding.

In a 2013 review, Herman (Dow AgroSciences) and Price (FDA, retired) argued that transgenesis is less disruptive than traditional breeding techniques because the latter routinely involve more changes (mutations, deletions, insertions and rearrangements) than the relatively limited changes (often single gene) in genetic engineering. The FDA found that all of the 148 transgenic events that they evaluated to be substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts, as have Japanese regulators for 189 submissions including combined-trait products. This equivalence was confirmed by more than 80 peer-reviewed publications. Hence, the authors argue, compositional equivalence studies uniquely required for GM food crops may no longer be justified on the basis of scientific uncertainty.

Allergenicity

A well-known risk of genetic modification is the introduction of an allergen. Allergen testing is routine for products intended for food, and passing those tests is part of the regulatory requirements. Organizations such as the European Green Party and Greenpeace emphasize this risk. A 2005 review of the results from allergen testing stated that "no biotech proteins in foods have been documented to cause allergic reactions". Regulatory authorities require that new modified foods be tested for allergenicity before they are marketed.

GMO proponents note that because of the safety testing requirements, the risk of introducing a plant variety with a new allergen or toxin is much smaller than from traditional breeding processes, which do not require such tests. Genetic engineering can have less impact on the expression of genomes or on protein and metabolite levels than conventional breeding or (non-directed) plant mutagenesis. Toxicologists note that "conventional food is not risk-free; allergies occur with many known and even new conventional foods. For example, the kiwi fruit was introduced into the U.S. and the European markets in the 1960s with no known human allergies; however, today there are people allergic to this fruit."

Genetic modification can also be used to remove allergens from foods, potentially reducing the risk of food allergies. A hypo-allergenic strain of soybean was tested in 2003 and shown to lack the major allergen that is found in the beans. A similar approach has been tried in ryegrass, which produces pollen that is a major cause of hay fever: here a fertile GM grass was produced that lacked the main pollen allergen, demonstrating that hypoallergenic grass is also possible.

The development of genetically modified products found to cause allergic reactions has been halted by the companies developing them before they were brought to market. In the early 1990s, Pioneer Hi-Bred attempted to improve the nutrition content of soybeans intended for animal feed by adding a gene from the Brazil nut. Because they knew that people have allergies to nuts, Pioneer ran in vitro and skin prick allergy tests. The tests showed that the transgenic soy was allergenic. Pioneer Hi-Bred therefore discontinued further development. In 2005, a pest-resistant field pea developed by the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation for use as a pasture crop was shown to cause an allergic reaction in mice. Work on this variety was immediately halted. These cases have been used as evidence that genetic modification can produce unexpected and dangerous changes in foods, and as evidence that safety tests effectively protect the food supply.

During the Starlink corn recalls in 2000, a variety of GM maize containing the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) protein Cry9C, was found contaminating corn products in U.S. supermarkets and restaurants. It was also found in Japan and South Korea. Starlink corn had only been approved for animal feed as the Cry9C protein lasts longer in the digestive system than other Bt proteins raising concerns about its potential allergenicity. In 2000, Taco Bell-branded taco shells sold in supermarkets were found to contain Starlink, resulting in a recall of those products, and eventually led to the recall of over 300 products. Sales of StarLink seed were discontinued and the registration for the Starlink varieties was voluntarily withdrawn by Aventis in October 2000. Aid sent by the United Nations and the United States to Central African nations was also found to be contaminated with StarLink corn and the aid was rejected. The U.S. corn supply has been monitored for Starlink Bt proteins since 2001 and no positive samples have been found since 2004. In response, GeneWatch UK and Greenpeace set up the GM Contamination Register in 2005. During the recall, the United States Centers for Disease Control evaluated reports of allergic reactions to StarLink corn, and determined that no allergic reactions to the corn had occurred.

Horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer is the movement of genes from one organism to another in a manner other than reproduction.

The risk of horizontal gene transfer between GMO plants and animals is very low and in most cases is expected to be lower than background rates. Two studies on the possible effects of feeding animals with genetically modified food found no residues of recombinant DNA or novel proteins in any organ or tissue samples. Studies found DNA from the M13 virus, Green fluorescent protein and RuBisCO genes in the blood and tissue of animals, and in 2012, a paper suggested that a specific microRNA from rice could be found at very low quantities in human and animal serum. Other studies however, found no or negligible transfer of plant microRNAs into the blood of humans or any of three model organisms.

Another concern is that the antibiotic resistance gene commonly used as a genetic marker in transgenic crops could be transferred to harmful bacteria, creating resistant superbugs. A 2004 study involving human volunteers examined whether the transgene from modified soy would transfer to bacteria that live in the human gut. As of 2012 it was the only human feeding study to have been conducted with GM food. The transgene was detected in three volunteers from a group of seven who had previously had their large intestines removed for medical reasons. As this gene transfer did not increase after the consumption of the modified soy, the researchers concluded that gene transfer did not occur. In volunteers with intact digestive tracts, the transgene did not survive. The antibiotic resistance genes used in genetic engineering are naturally found in many pathogens and antibiotics these genes confer resistance to are not widely prescribed.

Animal feeding studies

Reviews of animal feeding studies mostly found no effects. A 2014 review found that the performance of animals fed GM feed was similar to that of animals fed "isogenic non-GE crop lines". A 2012 review of 12 long-term studies and 12 multigenerational studies conducted by public research laboratories concluded that none had discovered any safety problems linked to consumption of GM food. A 2009 review by Magaña-Gómez found that although most studies concluded that modified foods do not differ in nutrition or cause toxic effects in animals, some did report adverse changes at a cellular level caused by specific modified foods. The review concluded that "More scientific effort and investigation is needed to ensure that consumption of GM foods is not likely to provoke any form of health problem". Dona and Arvanitoyannis' 2009 review concluded that "results of most studies with GM foods indicate that they may cause some common toxic effects such as hepatic, pancreatic, renal, or reproductive effects and may alter the hematological, biochemical, and immunologic parameters". Reactions to this review in 2009 and 2010 noted that Dona and Arvanitoyannis had concentrated on articles with an anti-modification bias that were refuted in peer-reviewed articles elsewhere. Flachowsky concluded in a 2005 review that food with a one-gene modification were similar in nutrition and safety to non-modified foods, but he noted that food with multiple gene modifications would be more difficult to test and would require further animal studies. A 2004 review of animal feeding trials by Aumaitre and others found no differences among animals eating genetically modified plants.

In 2007, Domingo's search of the PubMed database using 12 search terms indicated that the "number of references" on the safety of GM or transgenic crops was "surprisingly limited", and he questioned whether the safety of GM food had been demonstrated. The review also stated that its conclusions were in agreement with three earlier reviews. However, Vain found 692 research studies in 2007 that focused on GM crop and food safety and found increasing publication rates of such articles in recent years. Vain commented that the multidisciplinarian nature of GM research complicated the retrieval of studies based on it and required many search terms (he used more than 300) and multiple databases. Domingo and Bordonaba reviewed the literature again in 2011 and said that, although there had been a substantial increase in the number of studies since 2006, most were conducted by biotechnology companies "responsible of commercializing these GM plants." In 2016, Domingo published an updated analysis, and concluded that as of that time there were enough independent studies to establish that GM crops were not any more dangerous acutely than conventional foods, while still calling for more long-term studies.

Human studies

While some groups and individuals have called for more human testing of GM food, multiple obstacles complicate such studies. The General Accounting Office (in a review of FDA procedures requested by Congress) and a working group of the Food and Agriculture and World Health organizations both said that long-term human studies of the effect of GM food are not feasible. The reasons included lack of a plausible hypothesis to test, lack of knowledge about the potential long-term effects of conventional foods, variability in the ways humans react to foods and that epidemiological studies were unlikely to differentiate modified from conventional foods, which come with their own suite of unhealthy characteristics.

Additionally, ethical concerns guide human subject research. These mandate that each tested intervention must have a potential benefit for the human subjects, such as treatment for a disease or nutritional benefit (ruling out, e.g., human toxicity testing). Kimber claimed that the "ethical and technical constraints of conducting human trials, and the necessity of doing so, is a subject that requires considerable attention." Food with nutritional benefits may escape this objection. For example, GM rice has been tested for nutritional benefits, namely, increased levels of Vitamin A.

Controversial studies

Pusztai affair

Árpád Pusztai published the first peer-reviewed paper to find negative effects from GM food consumption in 1999. Pusztai fed rats potatoes transformed with the Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) gene from the Galanthus (snowdrop) plant, allowing the tuber to synthesise the GNA lectin protein. While some companies were considering growing GM crops expressing lectin, GNA was an unlikely candidate. Lectin is toxic, especially to gut epithelia. Pusztai reported significant differences in the thickness of the gut epithelium, but no differences in growth or immune system function.

On June 22, 1998, an interview on Granada Television's current affairs programme World in Action, Pusztai said that rats fed on the potatoes had stunted growth and a repressed immune system. A media frenzy resulted. Pusztai was suspended from the Rowett Institute. Misconduct procedures were used to seize his data and ban him from speaking publicly. The Rowett Institute and the Royal Society reviewed his work and concluded that the data did not support his conclusions. The work was criticized on the grounds that the unmodified potatoes were not a fair control diet and that any rat fed only potatoes would suffer from protein deficiency. Pusztai responded by stating that all diets had the same protein and energy content and that the food intake of all rats was the same.

Bt corn

A 2011 study was the first to evaluate the correlation between maternal and fetal exposure to Bt toxin produced in GM maize and to determine exposure levels of the pesticides and their metabolites. It reported the presence of pesticides associated with the modified foods in women and in pregnant women's fetuses. The paper and related media reports were criticized for overstating the results. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) posted a direct response, saying that the suitability of the ELISA method for detecting the Cry1Ab protein was not validated and that no evidence showed that GM food was the protein's source. The organization also suggested that even had the protein been detected its source was more likely conventional or organic food.

Séralini affair

In 2007, 2009, and 2011, Gilles-Éric Séralini published re-analysis studies that used data from Monsanto rat-feeding experiments for three modified maize varieties (insect-resistant MON 863 and MON 810 and glyphosate-resistant NK603). He concluded that the data showed liver, kidney and heart damage. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) then concluded that the differences were all within the normal range. EFSA also stated that Séralini's statistics were faulty. EFSA's conclusions were supported by FSANZ, a panel of expert toxicologists, and the French High Council of Biotechnologies Scientific Committee (HCB).

In 2012, Séralini's lab published a paper that considered the long-term effects of feeding rats various levels of GM glyphosate-resistant maize, conventional glyphosate-treated maize, and a mixture of the two strains. The paper concluded that rats fed the modified maize had severe health problems, including liver and kidney damage and large tumors. The study provoked widespread criticism. Séralini held a press conference just before the paper was released in which he announced the release of a book and a movie. He allowed reporters to have access to the paper before his press conference only if they signed a confidentiality agreement under which they could not report other scientists' responses to the paper. The press conference resulted in media coverage emphasizing a connection between GMOs, glyphosate, and cancer. Séralini's publicity stunt yielded criticism from other scientists for prohibiting critical commentary. Criticisms included insufficient statistical power and that Séralini's Sprague-Dawley rats were inappropriate for a lifetime study (as opposed to a shorter toxicity study) because of their tendency to develop cancer (one study found that more than 80% normally got cancer). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development guidelines recommended using 65 rats per experiment instead of the 10 in Séralini's. Other criticisms included the lack of data regarding food amounts and specimen growth rates, the lack of a dose–response relationship (females fed three times the standard dose showed a decreased number of tumours) and no identified mechanism for the tumour increases. Six French national academies of science issued an unprecedented joint statement condemning the study and the journal that published it. Food and Chemical Toxicology published many critical letters, with only a few expressing support. National food safety and regulatory agencies also reviewed the paper and dismissed it. In March 2013, Séralini responded to these criticisms in the same journal that originally published his study, and a few scientists supported his work. In November 2013, the editors of Food and Chemical Toxicology retracted the paper. The retraction was met with protests from Séralini and his supporters. In 2014, the study was republished by a different journal, Environmental Sciences Europe, in an expanded form, including the raw data that Séralini had originally refused to reveal.

Nutritional quality

Some plants are specifically genetically modified to be healthier than conventional crops. Golden rice was created to combat vitamin A deficiency by synthesizing beta carotene (which conventional rice does not).

Detoxification

One variety of cottonseed has been genetically modified to remove the toxin gossypol, so that it would be safe for humans to eat.

Environment

Genetically modified crops are planted in fields much like regular crops. There they interact directly with organisms that feed on the crops and indirectly with other organisms in the food chain. The pollen from the plants is distributed in the environment like that of any other crop. This distribution has led to concerns over the effects of GM crops on the environment. Potential effects include gene flow/genetic pollution, pesticide resistance and greenhouse gas emissions.

Non-target organisms

A major use of GM crops is in insect control through the expression of the cry (crystal delta-endotoxins) and Vip (vegetative insecticidal proteins) genes from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). Such toxins could affect other insects in addition to targeted pests such as the European corn borer. Bt proteins have been used as organic sprays for insect control in France since 1938 and the US since 1958, with no reported ill effects. Cry proteins selectively target Lepidopterans (moths and butterflies). As a toxic mechanism, cry proteins bind to specific receptors on the membranes of mid-gut (epithelial) cells, resulting in their rupture. Any organism that lacks the appropriate receptors in its gut is unaffected by the cry protein, and therefore is not affected by Bt. Regulatory agencies assess the potential for transgenic plants to affect non-target organisms before approving their commercial release.

In 1999, a paper stated that, in a laboratory environment, pollen from Bt maize dusted onto milkweed could harm the monarch butterfly. A collaborative research exercise over the following two years by several groups of scientists in the US and Canada studied the effects of Bt pollen in both the field and the laboratory. The study resulted in a risk assessment concluding that any risk posed to butterfly populations was negligible. A 2002 review of the scientific literature concluded that "the commercial large-scale cultivation of current Bt–maize hybrids did not pose a significant risk to the monarch population" and noted that despite large-scale planting of genetically modified crops, the butterfly's population was increasing. However, the herbicide glyphosate used to grow GMOs kills milkweed, the only food source of monarch butterflies, and by 2015 about 90% of the U.S. population has declined.

Lövei et al. analyzed laboratory settings and found that Bt toxins could affect non-target organisms, generally closely related to the intended targets. Typically, exposure occurs through the consumption of plant parts, such as pollen or plant debris, or through Bt ingestion by predators. A group of academic scientists criticized the analysis, writing: "We are deeply concerned about the inappropriate methods used in their paper, the lack of ecological context, and the authors’ advocacy of how laboratory studies on non-target arthropods should be conducted and interpreted".

Biodiversity

Crop genetic diversity might decrease due to the development of superior GM strains that crowd others out of the market. Indirect effects might affect other organisms. To the extent that agrochemicals impact biodiversity, modifications that increase their use, either because successful strains require them or because the accompanying development of resistance will require increased amounts of chemicals to offset increased resistance in target organisms.

Studies comparing the genetic diversity of cotton found that in the US diversity has either increased or stayed the same, while in India it has declined. This difference was attributed to the larger number of modified varieties in the US compared to India. A review of the effects of Bt crops on soil ecosystems found that in general they "appear to have no consistent, significant, and long-term effects on the microbiota and their activities in soil".

The diversity and number of weed populations has been shown to decrease in farm-scale trials in the United Kingdom and in Denmark when comparing herbicide-resistant crops to their conventional counterparts. The UK trial suggested that the diversity of birds could be adversely affected by the decrease in weed seeds available for foraging. Published farm data involved in the trials showed that seed-eating birds were more abundant on conventional maize after the application of the herbicide, but that there were no significant differences in any other crop or prior to herbicide treatment. A 2012 study found a correlation between the reduction of milkweed in farms that grew glyphosate-resistant crops and the decline in adult monarch butterfly populations in Mexico. The New York Times reported that the study "raises the somewhat radical notion that perhaps weeds on farms should be protected.

A 2005 study, designed to "simulate the impact of a direct overspray on a wetland" with four different agrochemicals (carbaryl (Sevin), malathion, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, and glyphosate in a Roundup formulation) by creating artificial ecosystems in tanks and then applying "each chemical at the manufacturer's maximum recommended application rates" found that "species richness was reduced by 15% with Sevin, 30% with malathion, and 22% with Roundup, whereas 2,4-D had no effect". The study has been used by environmental groups to argue that use of agrochemicals causes unintended harm to the environment and to biodiversity.

Secondary pests

Several studies documented surges in secondary pests within a few years of adoption of Bt cotton. In China, the main problem has been with mirids, which have in some cases "completely eroded all benefits from Bt cotton cultivation". A 2009 study in China concluded that the increase in secondary pests depended on local temperature and rainfall conditions and occurred in half the villages studied. The increase in insecticide use for the control of these secondary insects was far smaller than the reduction in total insecticide use due to Bt cotton adoption. A 2011 study based on a survey of 1,000 randomly selected farm households in five provinces in China found that the reduction in pesticide use in Bt cotton cultivars was significantly lower than that reported in research elsewhere: The finding was consistent with a hypothesis that more pesticide sprayings are needed over time to control emerging secondary pests, such as aphids, spider mites, and lygus bugs. Similar problems have been reported in India, with mealy bugs and aphids.

Gene flow

Genes from a GMO may pass to another organism just like an endogenous gene. The process is known as outcrossing and can occur in any new open-pollinated crop variety. As late as the 1990s this was thought to be unlikely and rare, and if it were to occur, easily eradicated. It was thought that this would add no additional environmental costs or risks - no effects were expected other than those already caused by pesticide applications. Introduced traits potentially can cross into neighboring plants of the same or closely related species through three different types of gene flow: crop-to-crop, crop-to-weedy, and crop-to-wild. In crop-to-crop, genetic information from a genetically modified crop is transferred to a non-genetically modified crop. Crop-to-weedy transfer refers to the transfer of genetically modified material to a weed, and crop-to-wild indicates transfer from a genetically modified crop to a wild, undomesticated plant and/or crop. There are concerns that the spread of genes from modified organisms to unmodified relatives could produce species of weeds resistant to herbicides that could contaminate nearby non-genetically modified crops, or could disrupt the ecosystem, This is primarily a concern if the transgenic organism has a significant survival capacity and can increase in frequency and persist in natural populations. This process, whereby genes are transferred from GMOs to wild relatives, is different from the development of so-called "superweeds" or "superbugs" that develop resistance to pesticides under natural selection.

In most countries environmental studies are required before approval of a GMO for commercial purposes, and a monitoring plan must be presented to identify unanticipated gene flow effects.

In 2004, Chilcutt and Tabashnik found Bt protein in kernels of a refuge crop (a conventional crop planted to harbor pests that might otherwise become resistant a pesticide associated with the GMO) implying that gene flow had occurred.

In 2005, scientists at the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology reported the first evidence of horizontal gene transfer of pesticide resistance to weeds, in a few plants from a single season; they found no evidence that any of the hybrids had survived in subsequent seasons.

In 2007, the U.S. Department of Agriculture fined Scotts Miracle-Gro $500,000 when modified DNA from GM creeping bentgrass, was found within relatives of the same genus (Agrostis) as well as in native grasses up to 21 km (13 mi) from the test sites, released when freshly cut, wind-blown grass.

In 2009, Mexico created a regulatory pathway for GM maize, but because Mexico is maize's center of diversity, concerns were raised about GM maize's effects on local strains. A 2001 report found Bt maize cross-breeding with conventional maize in Mexico. The data in this paper was later described as originating from an artifact and the publishing journal Nature stated that "the evidence available is not sufficient to justify the publication of the original paper", although it did not retract the paper. A subsequent large-scale study, in 2005, found no evidence of gene flow in Oaxaca. However, other authors claimed to have found evidence of such gene flow.

A 2010 study showed that about 83 percent of wild or weedy canola tested contained genetically modified herbicide resistance genes. According to the researchers, the lack of reports in the United States suggested that oversight and monitoring were inadequate. A 2010 report stated that the advent of glyphosate-resistant weeds could cause GM crops to lose their effectiveness unless farmers combined glyphosate with other weed-management strategies.

One way to avoid environmental contamination is genetic use restriction technology (GURT), also called "Terminator". This uncommercialized technology would allow the production of crops with sterile seeds, which would prevent the escape of GM traits. Groups concerned about food supplies had expressed concern that the technology would be used to limit access to fertile seeds. Another hypothetical technology known as "Traitor" or "T-GURT", would not render seeds sterile, but instead would require application of a chemical to GM crops to activate engineered traits. Groups such as Rural Advancement Foundation International raised concerns that further food safety and environmental testing needed to be done before T-GURT would be commercialized.

Escape of modified crops

The escape of genetically modified seed into neighboring fields, and the mixing of harvested products, is of concern to farmers who sell to countries that do not allow GMO imports.

In 1999 scientists in Thailand claimed they had discovered unapproved glyphosate-resistant GM wheat in a grain shipment, even though it was only grown in test plots. No mechanism for the escape was identified.

In 2000, Aventis StarLink GM corn was found in US markets and restaurants. It became the subject of a recall that started when Taco Bell-branded taco shells sold in supermarkets were found to contain it. StarLink was then discontinued. Registration for Starlink varieties was voluntarily withdrawn by Aventis in October 2000.

American rice exports to Europe were interrupted in 2006 when the LibertyLink modification was found in commercial rice crops, although it had not been approved for release. An investigation by the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) failed to determine the cause of the contamination.

In May 2013, unapproved glyphosate-resistant GM wheat (but that had been approved for human consumption) was discovered in a farm in Oregon in a field that had been planted with winter wheat. The strain was developed by Monsanto, and had been field-tested from 1998 to 2005. The discovery threatened US wheat exports which totaled $8.1 billion in 2012. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan temporarily suspended winter wheat purchases as a result of the discovery. As of August 30, 2013, while the source of the modified wheat remained unknown, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan had resumed placing orders.

Coexistence with conventional crops

The US has no legislation governing the relationship among mixtures of farms that grow organic, conventional, and GM crops. The country relies on a "complex but relaxed" combination of three federal agencies (FDA, EPA, and USDA/APHIS) and states' common law tort systems to manage coexistence. The Secretary of Agriculture convened an Advisory Committee on Biotechnology and 21st Century Agriculture (AC21) to study coexistence and make recommendations about the issue. The members of AC21 included representatives of the biotechnology industry, the organic food industry, farming communities, the seed industry, food manufacturers, State governments, consumer and community development groups, the medical profession, and academic researchers. AC21 recommended that a study assess the potential for economic losses to US organic farmers; that any serious losses lead to a crop insurance program, an education program to ensure that organic farmers put appropriate contracts in place and that neighboring GMO farmers take appropriate containment measures. Overall the report supported a diverse agriculture system supporting diverse farming systems.

The EU implemented regulations specifically governing co-existence and traceability. Traceability has become commonplace in the food and feed supply chains of most countries, but GMO traceability is more challenging given strict legal thresholds for unwanted mixing. Since 2001, conventional and organic food and feedstuffs can contain up to 0.9% of authorised modified material without carrying a GMO label. (any trace of non-authorised modification is cause for a shipment to be rejected). Authorities require the ability to trace, detect and identify GMOs, and the several countries and interested parties created a non-governmental organization, Co-Extra, to develop such methods.

Chemical use

Pesticides

Pesticides destroy, repel or mitigate pests (an organism that attacks or competes with a crop). A 2014 meta-analysis covering 147 original studies of farm surveys and field trials, and 15 studies from the researchers conducting the study, concluded that adoption of GM technology had reduced chemical pesticide use by 37%, with the effect larger for insect-tolerant crops than herbicide-tolerant crops. Some doubt still remains on whether the reduced amounts of pesticides used actually invoke a lower negative environmental effect, since there is also a shift in the types of pesticides used, and different pesticides have different environmental effects. In August 2015, protests occurred in Hawaii over the possibility that birth defects were being caused by the heavy use of pesticides on new strains of GM crops being developed there. Hawaii uses 17 times the amount of pesticides per acre compared to the rest of the US.

Herbicides

The development of glyphosate-tolerant (Roundup Ready) plants changed the herbicide use profile away from more persistent, higher toxicity herbicides, such as atrazine, metribuzin and alachlor, and reduced the volume and harm of herbicide runoff. A study by Chuck Benbrook concluded that the spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds had increased US herbicide use. That study cited a 23% increase (.3 kilograms/hectare) for soybeans from 1996–2006, a 43% (.9 kg/ha) increase for cotton from 1996–2010 and a 16% (.5 kg/ha) decrease for corn from 1996–2010. However, this study came under scrutiny because Benbrook did not consider the fact that glyphosate is less toxic than other herbicides, thus net toxicity may decrease even as use increases. Graham Brookes accused Benbrook of subjective herbicide estimates because his data, provided by the National Agricultural Statistics Service, does not distinguish between genetically modified and non-genetically modified crops. Brookes had earlier published a study that found that the use of biotech crops had reduced the volume and environmental impact of herbicide and other pesticides, which contradicted Benbrook. Brookes stated that Benbrook had made "biased and inaccurate" assumptions.

Insecticides

A claimed environmental benefit of Bt-cotton and maize is reduced insecticide use. A PG Economics study concluded that global pesticide use was reduced by 286,000 tons in 2006, decreasing pesticidal environmental impact by 15%. A survey of small Indian farms between 2002 and 2008 concluded that Bt cotton adoption had led to higher yields and lower pesticide use. Another study concluded that insecticide use on cotton and corn during the years 1996 to 2005 fell by 35,600,000 kilograms (78,500,000 lb) of active ingredient, roughly equal to the annual amount applied in the European Union. A Bt cotton study in six northern Chinese provinces from 1990 to 2010 concluded that it halved the use of pesticides and doubled the level of ladybirds, lacewings and spiders and extended environmental benefits to neighbouring crops of maize, peanuts and soybeans.

Resistant insect pests

Resistance evolves naturally after a population has been subjected to selection pressure via repeated use of a single pesticide. In November 2009, Monsanto scientists found that the pink bollworm had become resistant to first generation Bt cotton in parts of Gujarat, India—that generation expresses one Bt gene, Cry1Ac. This was the first instance of Bt resistance confirmed by Monsanto. Similar resistance was later identified in Australia, China, Spain and the US.

One strategy to delay Bt-resistance is to plant pest refuges using conventional crops, thereby diluting any resistant genes. Another is to develop crops with multiple Bt genes that target different receptors within the insect. In 2012, a Florida field trial demonstrated that army worms were resistant to Dupont-Dow's GM corn. This resistance was discovered in Puerto Rico in 2006, prompting Dow and DuPont to stop selling the product there. The European corn borer, one of Bt's primary targets, is also capable of developing resistance.

Economy

GM food's economic value to farmers is one of its major benefits, including in developing nations. A 2010 study found that Bt corn provided economic benefits of $6.9 billion over the previous 14 years in five Midwestern states. The majority ($4.3 billion) accrued to farmers producing non-Bt corn. This was attributed to European corn borer populations reduced by exposure to Bt corn, leaving fewer to attack conventional corn nearby. Agriculture economists calculated that "world surplus [increased by] $240.3 million for 1996. Of this total, the largest share (59%) went to U.S. farmers. Seed company Monsanto received the next largest share (21%), followed by US consumers (9%), the rest of the world (6%), and the germplasm supplier, Delta and Pine Land Company (5%)." PG Economics comprehensive 2012 study concluded that GM crops increased farm incomes worldwide by $14 billion in 2010, with over half this total going to farmers in developing countries.

The main Bt crop grown by small farmers in developing countries is cotton. A 2006 review of Bt cotton findings by agricultural economists concluded, "the overall balance sheet, though promising, is mixed. Economic returns are highly variable over years, farm type, and geographical location". However, environmental activist Mark Lynas said that complete rejection of genetic engineering is "illogical and potentially harmful to the interests of poorer peoples and the environment".

In 2013, the European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC) asked the EU to allow the development of agricultural GM technologies to enable more sustainable agriculture, by employing fewer land, water and nutrient resources. EASAC also criticizes the EU's "timeconsuming and expensive regulatory framework" and said that the EU had fallen behind in the adoption of GM technologies.

Developing nations

Disagreements about developing nations include the claimed need for increased food supplies, and how to achieve such an increase. Some scientists suggest that a second Green Revolution including use of modified crops is needed to provide sufficient food. The potential for genetically modified food to help developing nations was recognised by the International Assessment of Agricultural Science and Technology for Development, but as of 2008 they had found no conclusive evidence of a solution.

Skeptics such as John Avise claim that apparent shortages are caused by problems in food distribution and politics, rather than production. Other critics say that the world has so many people because the second green revolution adopted unsustainable agricultural practices that left the world with more mouths to feed than the planet can sustain. Pfeiffer claimed that even if technological farming could feed the current population, its dependence on fossil fuels, which in 2006 he incorrectly predicted would reach peak output in 2010, would lead to a catastrophic rise in energy and food prices.

Claimed deployment constraints to developing nations include the lack of easy access, equipment costs and intellectual property rights that hurt developing countries. The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), an aid and research organization, was praised by the World Bank for its efforts, but the bank recommended that they shift to genetics research and productivity enhancement. Obstacles include access to patents, commercial licenses and the difficulty that developing countries have in accessing genetic resources and other intellectual property. The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture attempted to remedy this problem, but results have been inconsistent. As a result, "orphan crops", such as teff, millets, cowpeas and indigenous plants, which are important in these countries receive little investment.

Writing about Norman Borlaug's 2000 publication Ending world hunger: the promise of biotechnology and the threat of antiscience zealotry, the authors argued that Borlaug's warnings were still true in 2010:

GM crops are as natural and safe as today's bread wheat, opined Dr. Borlaug, who also reminded agricultural scientists of their moral obligation to stand up to the antiscience crowd and warn policy makers that global food insecurity will not disappear without this new technology and ignoring this reality would make future solutions all the more difficult to achieve.

Yield

US maize yields were flat until the 1930s, when the adoption of conventional hybrid seeds caused them to increase by ~.8 bushels/acre (1937–1955). Thereafter a combination of improved genetics, fertilizer and pesticide availability and mechanization raised the rate of increase to 1.9 bushels per acre per year. In the years since the advent of GM maize, the rate increased slightly to 2.0. Average US maize yields were 174.2 bushels per acre in 2014.

Commercial GM crops have traits that reduce yield loss from insect pressure or weed interference.

2014 review

A 2014 review, concluded that GM crops' effects on farming were positive. According to The Economist, the meta-analysis considered all published English-language examinations of the agronomic and economic impacts between 1995 and March 2014. The study found that herbicide-tolerant crops have lower production costs, while for insect-resistant crops the reduced pesticide use was offset by higher seed prices, leaving overall production costs about the same.

Yields increased 9% for herbicide tolerance and 25% for insect resistance. Farmers who adopted GM crops made 69% higher profits than those who did not. The review found that GM crops help farmers in developing countries, increasing yields by 14 percentage points.

The researchers considered some studies that were not peer-reviewed, and a few that did not report sample sizes. They attempted to correct for publication bias, by considering sources beyond academic journals. The large data set allowed the study to control for potentially confounding variables such as fertiliser use. Separately, they concluded that the funding source did not influence study results.

2010 review

A 2010 article, supported by CropLife International summarised the results of 49 peer reviewed studies. On average, farmers in developed countries increased yields by 6% and 29% in developing countries.

Tillage decreased by 25–58% on herbicide-resistant soybeans. Glyphosate-resistant crops allowed farmers to plant rows closer together as they did not have to control post-emergent weeds with mechanical tillage. Insecticide applications on Bt crops were reduced by 14–76%. 72% of farmers worldwide experienced positive economic results.

2009 review

In 2009, the Union of Concerned Scientists, a group opposed to genetic engineering and cloning of food animals, summarized peer-reviewed studies on the yield contribution of GM soybeans and maize in the US. The report concluded that other agricultural methods had made a greater contribution to national crop yield increases in recent years than genetic engineering.

Wisconsin study

A study unusually published as correspondence rather than as an article examined maize modified to express four traits (resistance to European corn borer, resistance to corn root worm, glyphosate tolerance and glyfosinate tolerance) singly and in combination in Wisconsin fields from 1990–2010. The variance in yield from year to year was reduced, equivalent to a yield increase of 0.8–4.2 bushels per acre. Bushel per acre yield changes were +6.4 for European corn borer resistance, +5.76 for glufosinate tolerance, −5.98 for glyphosate tolerance and −12.22 for corn rootworm resistance. The study found interactions among the genes in multi-trait hybrid strains, such that the net effect varied from the sum of the individual effects. For example, the combination of European corn borer resistance and glufosinate tolerance increased yields by 3.13, smaller than either of the individual traits.

Market dynamics

The seed industry is dominated by a small number of vertically integrated firms. In 2011, 73% of the global market was controlled by 10 companies.

In 2001, the USDA reported that industry consolidation led to economies of scale, but noted that the move by some companies to divest their seed operations questioned the long-term viability of these conglomerates. Two economists have said that the seed companies' market power could raise welfare despite their pricing strategies, because "even though price discrimination is often considered to be an unwanted market distortion, it may increase total welfare by increasing total output and by making goods available to markets where they would not appear otherwise."

Market share gives firms the ability to set or influence price, dictate terms, and act as a barrier to entry. It also gives firms bargaining power over governments in policy making. In March 2010, the US Department of Justice and the US Department of Agriculture held a meeting in Ankeny, Iowa, to look at the competitive dynamics in the seed industry. Christine Varney, who heads the antitrust division in the Justice Department, said that her team was investigating whether biotech-seed patents were being abused. A key issue was how Monsanto licenses its patented glyphosate-tolerance trait that was in 93 percent of US soybeans grown in 2009. About 250 family farmers, consumers and other critics of corporate agriculture held a town meeting prior to the government meeting to protest Monsanto's purchase of independent seed companies, patenting seeds and then raising seed prices.

Intellectual property

Traditionally, farmers in all nations saved their own seed from year to year. However, since the early 1900s hybrid crops have been widely used in the developed world and seeds to grow these crops are purchased each year from seed producers. The offspring of the hybrid corn, while still viable, lose hybrid vigor (the beneficial traits of the parents). This benefit of first-generation hybrid seeds is the primary reason for not planting second-generation seed. However, for non-hybrid GM crops, such as GM soybeans, seed companies use intellectual property law and tangible property common law, each expressed in contracts, to prevent farmers from planting saved seed. For example, Monsanto's typical bailment license (covering transfer of the seeds themselves) forbids saving seeds, and also requires purchasers to sign a separate patent license agreement.

Corporations say that they need to prevent seed piracy, to fulfill financial obligations to shareholders, and to finance further development. DuPont spent approximately half its $2 billion research and development (R&D) budget on agriculture in 2011 while Monsanto spends 9–10% of sales on R&D.

Detractors such as Greenpeace say that patent rights give corporations excessive control over agriculture. The Center for Ecoliteracy claimed that "patenting seeds gives companies excessive power over something that is vital for everyone". A 2000 report stated, "If the rights to these tools are strongly and universally enforced - and not extensively licensed or provided pro bono in the developing world – then the potential applications of GM technologies described previously are unlikely to benefit the less developed nations of the world for a long time" (i.e. until after the restrictions expire).

Monsanto has patented its seed and it obligates farmers who choose to buy its seeds to sign a license agreement, obligating them store or sell, but not plant, all the crops that they grow.

Besides large agri-businesses, in some instances, GM crops are also provided by science departments or research organisations which have no commercial interests.

Lawsuits filed against farmers for patent infringement

Monsanto has filed patent infringement suits against 145 farmers, but proceeded to trial with only 11. In some of the latter, the defendants claimed unintentional contamination by gene flow, but Monsanto won every case. Monsanto Canada's Director of Public Affairs stated, "It is not, nor has it ever been Monsanto Canada's policy to enforce its patent on Roundup Ready crops when they are present on a farmer's field by accident ... Only when there has been a knowing and deliberate violation of its patent rights will Monsanto act." In 2009 Monsanto announced that after its soybean patent expires in 2014, it will no longer prohibit farmers from planting soybean seeds that they grow.

One example of such litigation is the Monsanto v. Schmeiser case. This case is widely misunderstood. In 1997, Percy Schmeiser, a canola breeder and grower in Bruno, Saskatchewan, discovered that one of his fields had canola that was resistant to Roundup. He had not purchased this seed, which had blown onto his land from neighboring fields. He later harvested the area and saved the crop in the back of a pickup truck. Before the 1998 planting, Monsanto representatives informed Schmeiser that using this crop for seed would infringe the patent, and offered him a license, which Schmeiser refused. According to the Canadian Supreme Court, after this conversation "Schmeiser nevertheless took the harvest he had saved in the pick-up truck to a seed treatment plant and had it treated for use as seed. Once treated, it could be put to no other use. Mr. Schmeiser planted the treated seed in nine fields, covering approximately 1,000 acres in all ... A series of independent tests by different experts confirmed that the canola Mr. Schmeiser planted and grew in 1998 was 95 to 98 percent Roundup resistant." After further negotiations between Schmeiser and Monsanto broke down, Monsanto sued Schmeiser for patent infringement and prevailed in the initial case. Schmeiser appealed and lost, and appealed again to the Canadian Supreme Court, which in 2004 ruled 5 to 4 in Monsanto's favor, stating that "it is clear on the findings of the trial judge that the appellants saved, planted, harvested and sold the crop from plants containing the gene and plant cell patented by Monsanto".

International trade

GM crops have been the source of international trade disputes and tensions within food-exporting nations over whether introduction of genetically modified crops would endanger exports to other countries.