Jewish views on slavery are varied both religiously and historically. Judaism's ancient and medieval religious texts contain numerous laws governing the ownership and treatment of slaves. Texts that contain such regulations include the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud, the 12th-century Mishneh Torah by rabbi Maimonides, and the 16th-century Shulchan Aruch by rabbi Yosef Karo. The original Israelite slavery laws found in the Hebrew Bible bear some resemblance to the 18th-century BCE slavery laws of Hammurabi. The regulations changed over time. The Hebrew Bible contained two sets of laws, one for Canaanite slaves, and a more lenient set of laws for Hebrew slaves. From the time of the Pentateuch, the laws designated for Canaanites were applied to all non-Hebrew slaves. The Talmud's slavery laws, which were established in the second through the fifth centuries CE, contain a single set of rules for all slaves, although there are a few exceptions where Hebrew slaves are treated differently from non-Hebrew slaves. The laws include punishment for slave owners that mistreat their slaves. In the modern era, when the abolitionist movement sought to outlaw slavery, some supporters of slavery used the laws to provide religious justification for the practice of slavery.

Broadly, the Biblical and Talmudic laws tended to consider slavery a form of contract between persons, theoretically reducible to voluntary slavery, unlike chattel slavery, where the enslaved person is legally rendered the personal property (chattel) of the slave owner. Hebrew slavery was prohibited during the Rabbinic era for as long as the Temple in Jerusalem is not reconstructed (i.e., the last two millennia). Although not prohibited, Jewish ownership of non-Jewish slaves was constrained by Rabbinic authorities since non-Jewish slaves were to be offered conversion to Judaism during their first 12-months term as slaves. If accepted, the slaves were to become Jews, hence redeemed immediately. If rejected, the slaves were to be sold to non-Jewish owners. Accordingly, the Jewish law produced a constant stream of Jewish convertors with previous slave experience. Additionally, Jews were required to redeem Jewish slaves from non-Jewish owners, making them a privileged enslavement item, albeit temporary. The combination has made Jews less likely to participate in enslavement and slave trade.

Historically, some Jewish people owned and traded slaves. They participated in the medieval slave trade in Europe up to about the 12th century. Several scholarly works have been published to rebut the antisemitic canard of Jewish domination of the slave trade in Africa and the Americas in the later centuries, and to show that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery. They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every Spanish territory in North America and the Caribbean, and "in no period did they play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades" (Wim Klooster quoted by Eli Faber).

American mainland colonial Jews imported slaves from Africa at a rate proportionate to the general population. As slave sellers, their role was more marginal, although their involvement in the Brazilian and Caribbean trade is believed to be considerably more significant. Jason H. Silverman, a historian of slavery, describes the part of Jews in slave trading in the southern United States as "minuscule", and writes that the historical rise and fall of slavery in the United States would not have been affected at all had there been no Jews living in the American South. Jews accounted for 1.25% of all Southern slave owners, and were not significantly different from other slave owners in their treatment of slaves.

The Exodus

The story of the Exodus from Egypt, as related in the Torah, has shaped the Jewish people throughout history. Briefly outlined, the story recounts the experience of the Israelites under Egyptian enslavement, God's promise to redeem them from slavery, God's punishment of the Egyptians, and the Israelite redemption and departure from Egypt. The Exodus story has been interpreted and reinterpreted in every era and in every location to suit or challenge cultural norms. The result over time has been a steady increase in the governance of masters in favor of slaves' rights and eventually the complete prohibition of slavery.

Biblical era

Ancient Israelite society allowed slavery; however, total domination of one human being by another was not permitted. Rather, slavery in antiquity among the Israelites was closer to what would later be called indentured servitude. Slaves were seen as an essential part of a Hebrew household. In fact, there were cases in which, from a slave's point of view, the stability of servitude under a family in which the slave was well-treated would have been preferable to economic freedom.

It is impossible for scholars to quantify the number of slaves that were owned by Hebrews in ancient Israelite society, or what percentage of households owned slaves, but it is possible to analyze social, legal, and economic impacts of slavery.

The Hebrew Bible contains two sets of rules governing slaves: one set for Hebrew slaves (Lev 25:39-43) and a second set for Canaanite slaves (Lev 25:45-46). The main source of non-Hebrew slaves were prisoners of war. Hebrew slaves, in contrast to non-Hebrew slaves, became slaves either because of extreme poverty (in which case they could sell themselves to an Israelite owner) or because of inability to pay a debt. According to the Hebrew Bible, non-Hebrew slaves were drawn primarily from the neighboring Canaanite nations, and religious justification was provided for the enslavement of these neighbors: the rules governing Canaanites was based on a curse aimed at Canaan, a son of Ham, but in later eras the Canaanite slavery laws were stretched to apply to all non-Hebrew slaves.

The laws governing non-Hebrew slaves were more harsh than those governing Hebrew slaves: non-Hebrew slaves could be owned permanently, and bequeathed to the owner's children, whereas Hebrew slaves were treated as servants, and were released after six years of service or the occurrence of a jubilee year. One scholar suggests that the distinction was due to the fact that non-Hebrew slaves were subject to the curse of Canaan, whereas God did not want Jews to be slaves because he freed them from Egyptian enslavement.

The laws governing Hebrew slaves were more lenient than laws governing non-Hebrew slaves, but a single Hebrew word, ebed (meaning slave or servant, cognate to the Arabic abd) is used for both situations. In English translations of the Bible, the distinction is sometimes emphasized by translating the word as "slave" in the context of non-Hebrew slaves, and "servant" or "bondman" for Hebrew slaves. Ebed is also used, throughout the Hebrew Bible, to denote government officials, sometimes high-ranking (for example, Nathan-melech, whose seal was discovered in archeological excavations. In translations of 2 Kings 23:11 where Nathan-melech is noticed, his title is translated as 'chamberlain,' 'officer' or 'official').

Most slaves owned by Israelites were non-Hebrew, and scholars are not certain what percentage of slaves were Hebrew: Ephraim Urbach, a distinguished scholar of Judaism, maintains that Israelites rarely owned Hebrew slaves after the Maccabean era, although it is certain that Israelites owned Hebrew slaves during the time of the Babylonian exile. Another scholar suggests that Israelites continued to own Hebrew slaves through the Middle Ages, but that the Biblical rules were ignored, and Hebrew slaves were treated the same as non-Hebrews.

The Torah forbids the return of runaway slaves who escape from their foreign land and their bondage and arrive in the Land of Israel. Furthermore, the Torah demands that such former slaves be treated equally to any other resident alien. This law is unique in the Ancient Near East.

Talmudic era

In the early Common Era, the regulations concerning slave-ownership by Jews underwent an extensive expansion and codification within the Talmud. The precise issues that necessitated a clarification to the laws is still up for debate. The majority of current scholarly opinion holds that pressures to assimilate during the late Roman to early medieval period resulted in an attempt by Jewish communities to reinforce their own identities by drawing distinctions between their practices and the practices of non-Jews. One author, however, has proposed that they could include factors such as ownership of non-Canaanite slaves, the continuing practice of owning Jewish slaves, or conflicts with Roman slave-ownership laws. Thus, the Babylonian Talmud (redacted in 500 CE) contains an extensive set of laws governing slavery, which is more detailed than found in the Torah.

The major change found in the Talmud's slavery laws was that a single set of rules, with a few exceptions, governs both Jewish slaves and non-Jewish slaves. Another change was that the distinction between Hebrew and non-Hebrew slaves began to diminish as the Talmud expanded during this period. This included an expanded set of obligations the owner incurred toward the slave as well as codifying the process for manumission (the freeing from slavery). It also included a large set of conditions, that allowed or required manumission to include requirements for education of slaves, expanding disability manumission, and in cases of religious conversion or necessity. These restrictions were based on the Biblical injunction to treat slaves well with the reinforcement of the memory of Egyptian slavery which Jews were urged to remember by their scriptural texts. However, historian Josephus wrote that the seven-year automatic release was still in effect if the slavery was a punishment for a crime the slave committed (as opposed to voluntary slavery due to poverty). In addition, the notion of Canaanite slaves from the Jewish Bible is expanded to all non-Jewish slaves.

Significant effort is given in the Talmud to address the property rights of slaves. While the Torah only refers to a slave's specific ability to collect gleanings, Talmudic sources interpret this commandment to include the right to own property more generally, and even "purchase" a portion of their own labor from the master. Hezser notes the often confusing mosaic of Talmudic laws distinguishes between finding property during work and earning property as a result of work. While the Talmud affirmed that self-redemption of slaves (Jewish or not) was always permitted, it noted that conditionless manumission by the owner was generally a violation of legal precept. The Talmud however, also included a varied list of circumstances and conditions that overrode this principle and mandated manumission. Conditions such as ill-treatment, oral promise, marriage to a free-woman, escape, inclusion in religious ceremony, and desire to visit the Holy Land all required the master to provide the slave with a deed of manumission, presented to him with witnesses. Failure to comply would result in excommunication.

It is apparent that Jews still owned Jewish slaves in the Talmudic era because Talmudic authorities tried to denounce the practice that Jews could sell themselves into slavery if they were poverty-stricken. In particular, the Talmud said that Jews should not sell themselves to non-Jews, and if they did, the Jewish community was urged to ransom or redeem the slave.

While Jews did take slavery as a given, just as in other ancient societies, slaves in Jewish households could expect more compassionate treatment.

Methods of acquisition

Acquisition of a non-Jewish slave by a Jew is expressly stated in the Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 3:1 [8a]) as being acquired in the following manner: A child who has been abandoned in the marketplace and who has been taken-up by a stranger, if his parents cannot be found, nor two witnesses who are able to claim that the child is the son of so-and-so, the child is then called an asūfī ("foundling") and may be handled as a slave by its patron, namely, the person who took him in. Even so, this is on the condition that the child is so small that he is unable to move about on his own volition, from one distant place to another distant place. Had three years passed without objection, the child can be handled as his bona fide slave. In this case, the child is circumcised, immersed in a ritual bath, and obligated to keep the commandments as Jewish women.

Maimonides, in his Code of Jewish law, lists other methods by which non-Jewish slaves may be acquired, citing the Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Kiddushin: "A Canaanite slave is acquired either by money, or by writ, or by usucaption. How is usucaption performed exactly when acquiring slaves? It is performed by making use of them, just as one would do with slaves before their master. How? Had he unlaced his shoe, or shod him with a shoe, or had he carried his items [of clothing] to the bath house, or helped him to get undressed, or rubbed him down with [medicinal] oil, scratched [his back] for him, or helped him to get dressed, or had he lifted-up his master, in such [ways] he has acquired him [as a slave]. [...] Had he forcibly attacked him and brought him along with him, he has acquired thereby a slave, since slaves are acquired by having them drawn-along in such a manner. [...] A slave who is but a child is acquired by drawing him along, without the necessity of having to attack him."

A Jewish slave is acquired differently, namely, when a Jewish court of law sells him into limited bondage (unto a Jewish master) for having engaged in thefts and not having that which to pay. In such cases, he does not work beyond six years. A Jewish bondmaid is sold by her father into servitude, usually because of severe poverty, but the girl's master, as a first resort, is required to betroth her in marriage after using her as his bondmaid. These sanctions only apply when the entire nation of Israel is settled in their own land and the laws of the Jubilee (Hebrew: יובל) have been re-instated.

Curse of Ham as a justification for slavery

Some scholars have asserted that the Curse of Ham described in Judaism's religious texts was a justification for slavery – citing the Tanakh (Jewish Bible) verses Genesis 9:20–27 and the Talmud. Scholars such as David M. Goldenberg have analyzed the religious texts, and concluded that those conclusions on faulty interpretations of Rabbinical sources: Goldenberg concludes that the Judaic texts do not explicitly contain anti-black precepts, but instead later race-based interpretations were applied to the texts by later, non-Jewish analysts. While the episode about Ham and his father Noah displays like a banner the actions of the fathers unto the shame of their sons, the codifiers of Jewish law assert that a Canaanite slave is obligated to perform certain mitzvot, just as Jewish women do, making him of a higher rank than ordinary gentiles when there is a question on whose life should be saved first. Moreover, according to the Hebrew Bible (Exo. 21:26-ff.), whenever a Canaanite slave is set free from his yoke by losing either a tooth or an eye, or one of twenty-four chief limbs in a man's body that cannot be replaced, where the Torah says of him, “he shall set him free,” according to the exponents of Jewish law, the sense here is that the same emancipated slave becomes a "freeborn" (benei ḥorīn) and is received in the Jewish fold and is permitted to marry a daughter of Israel. However, his emancipation must be followed by a written bill of manumission (sheṭar shiḥrūr) by the rabbinic court of Israel, and must also be followed by a second immersion in a ritual bath. Hence: a Canaanite slave's bondage was meant to elevate himself at a later juncture in life, although his Master in ordinary circumstances is under no constraints to set him free, unless he were physically and openly maimed.

The rules governing a Canaanite slave are used generically, and may apply to any non-Jew (gentile) held in bondage by an Israelite.

According to Rashi, citing an earlier Talmudic source, the heathen were never included in the sanction of possessing slaves as the children of Israel were permitted to do, for the Scripture says (Leviticus 25:44): "Of them you shall buy, etc.", meaning, "Israel alone is permitted to buy from them [enslaved persons], but they are not permitted to buy [enslaved persons] from you, nor from one another."

Female slaves

The classical rabbis instructed that masters could never marry female slaves. They would have to be manumitted first; similarly, male slaves could not be allowed to marry Jewish women. Unlike the biblical instruction to sell thieves into slavery (if they were caught during daylight and could not repay the theft), the rabbis ordered that female Israelites could never be sold into slavery for this reason. Sexual relations between a slave owner and engaged slaves is prohibited in the Torah (Lev. 19:20-22). However, the Torah allows sex with non-engaged slaves, by clarifying that if she is engaged when the master has sex with her, "they are not to be put to death, since she was not freed" (which implies that a woman's slave status has direct bearing on whether she can be used for sex).

Freeing a slave

The Tanakh contains the rule that Jewish slaves would be released following six years of service, but that non-Jewish slaves (barring a long list of conditions including conversion, or disability) could potentially be held indefinitely. The Talmud codified and expanded the list of conditions requiring manumission to include religious necessity, conversion, escape, maltreatment, and codified slaves' property rights and rights to education. Freeing a non-Jewish slave was seen as a religious conversion, and involved a second immersion in a ritual bath (mikveh). Jewish authorities of the Middle Ages argued against the Biblical rule that provided freedom for severely injured slaves.

Treatment of slaves

The Torah and the Talmud contain various rules about how to treat slaves. Biblical rules for treatment of Jewish slaves were more lenient than for non-Jewish slaves and the Talmud insisted that Jewish slaves should be granted similar food, drink, lodging, and bedding, to that which their master would grant to himself. Laws existed that specified punishment of owners that killed slaves. Jewish slaves were often treated as property; for example, they were not allowed to be counted towards the quorum, equal to 10 men, needed for public worship. Maimonides and other halachic authorities forbade or strongly discouraged any unethical treatment of slaves, Jewish or not. Some accounts indicate that Jewish slave-owners were affectionate, and would not sell slaves to a harsh master and that Jewish slaves were treated as members of the slave-owner's family.

Scholars are unsure to what extent the laws encouraging humane treatment were followed. In the 19th century, Jewish scholars such as Moses Mielziner and Samuel Krauss studied slave-ownership by ancient Jews, and generally concluded that Jewish slaves were treated as merely temporary bondsman, and that Jewish owners treated slaves with special compassion. However, 20th century scholars such as Solomon Zeitlin and Ephraim Urbach, examined Jewish slave-ownership practices more critically, and their historical accounts generally conclude that Jews did own slaves at least through the Maccabbean period, and that it was probably more ubiquitous and humane than earlier scholars had maintained. Professor Catherine Hezser explains the differing conclusions by suggesting that the 19th century scholars were "emphasizing the humanitarian aspects and moral values of ancient Judaism, Mielziner, Grunfeld, Farbstein, and Krauss [to argue] that the Jewish tradition was not inferior to early Christian teachings on slaves and slavery."

Converting or circumcising non-Jewish slaves

The Talmudic laws required Jewish slave owners to try to convert non-Jewish slaves to Judaism. Other laws required slaves, if not converted, to be circumcised and undergo ritual immersion in a bath (mikveh). A 4th century Roman law prevented the circumcision of non-Jewish slaves, so the practice may have declined at that time, but increased again after the 10th century. Jewish slave owners were not permitted to drink wine that had been touched by an uncircumcised person so there was always a practical need, in addition to the legal requirement, to circumcise slaves.

Although conversion to Judaism was a possibility for slaves, rabbinic authorities Maimonides and Karo discouraged it on the basis that Jews were not permitted (in their time) to proselytize; slaveowners could enter into special contracts by which they agree not to convert their slaves. Furthermore, to convert a slave into Judaism without the owner's permission was seen as causing harm to the owner, on the basis that it would rob the owner of the slave's ability to work during the Sabbath, and it would prevent them from selling the slave to non-Jews.

One exceptional issue, codified by Maimonides, was the requirement allocating a 12-month period when a Jewish owner of non-Jewish would propose conversion to the slave. If accepted, slavery would transform from Canaanite to Hebrew, triggering the set of rights associated with the latter, including an early release. As noted above, Maimonides considered Hebrew slavery prohibited until Israel is reestablished with full religious rigor. Consequently, the release of a slave was to be immediate upon conversion. If unaccepted, the Jewish slave owner was required to sell the slave to non-Jews by the end of the 12-month period (Mishneh Torah, Sefer Kinyan 5:8:14). If the non-Jewish slave conditions slavery by non-conversion prior to enslavement, the 12-month period does not apply. Instead, the slave might elect to convert at any time, with the consequences described (Ibid). It is unclear to what extent Maimonides's prescription was actually followed, but some scholars believe it played a role in the formation of Ashkenazi Jews, partially formed from converted slaves freed according to Maimonides' procedure. Applications of this protocol were also proposed concerning the early formation of communities of African-American Jews.

Post-Talmud to 1800s

Jewish slaves and masters

Christian leaders, including Pope Gregory the Great (served 590-604), objected to Jewish ownership of Christian slaves, due to concerns about conversion to Judaism and the Talmudic mandate to circumcise slaves. The first prohibition of Jews owning Christian slaves was made by Constantine I in the 4th century. The prohibition was repeated by subsequent councils: Fourth Council of Orléans (541), Paris (633), Fourth Council of Toledo (633), the Synod of Szabolcs (1092) extended the prohibition to Hungary, Ghent (1112), Narbonne (1227), Béziers (1246). It was part of Saint Benedict's rule that Christian slaves were not to serve Jews.

Despite the prohibition, Jews participated to some extent in slave trading during the Middle Ages. The extent of Jewish participation in the medieval slave trade has been subject to ongoing discourse among the historians. Michael Toch noted that the idea of a Jewish dominance of or even monopoly over the slave trade of medieval Christian Europe, while present in some older historical works, is generally unfounded. Jews were the chief traders in the segment of Christian slaves at some epochs and played a significant role in the slave trade in some regions. According to other sources, Medieval Christians greatly exaggerated the supposed Jewish control over trade and finance, and became obsessed with alleged Jewish plots to enslave, convert, or sell non-Jews. Most European Jews lived in poor communities on the margins of Christian society; they continued to suffer most of the legal disabilities associated with slavery. Jews participated in routes that had been created by Christians or Muslims but rarely created new trading routes.

During the Middle Ages, Jews acted as slave-traders in Slavonia North Africa, Baltic States, Central and Eastern Europe, al-Andalus and later Spain and Portugal, and Mallorca. The most significant Jewish involvement in the slave-trade was in Spain and Portugal during the 10th to 15th centuries.

Jewish participation in the slave trade was recorded as beginning in the 5th century, when Pope Gelasius permitted Jews to introduce slaves from Gaul into Italy, on the condition that they were non-Christian. In the 8th century, Charlemagne (ƒ 768-814) explicitly allowed Jews to act as intermediaries in the slave trade. In the 10th century, Spanish Jews traded in Slavonian slaves, whom the Caliphs of Andalusia purchased to form their bodyguards. In Bohemia, Jews purchased these Slavonian slaves for exportation to Spain and the west of Europe. William the Conqueror brought Jewish slave-traders with him from Rouen to England in 1066. At Marseilles in the 13th century, there were two Jewish slave-traders, as opposed to seven Christians.

Middle Ages historical records from the 9th century describe two routes by which Jewish slave-dealers carried slaves from west to east and from east to west. According to Abraham ibn Yakub, Byzantine Jewish merchants bought Slavs from Prague to be sold as slaves. Similarly, the Jews of Verdun, around the year 949, purchased slaves in their neighborhood and sold them in Spain.

Jews continued to own slaves during the 16th through 18th centuries, and ownership practices were still governed by Biblical and Talmudic laws. Myriad Hebrew and other sources indicate that owning slaves—particularly women of Slavic origin—was uniquely prevalent during this period among the Jewish households of the urban centres of the Ottoman Empire.

Halachic developments

Treatment of slaves

Jewish laws governing treatment of slaves were restated in the 12th century by noted rabbi Maimonides in his book Mishneh Torah, and again in the 16th century by Rabbi Yosef Karo in his book Shulchan Aruch.

The legal prohibition against Jews owning Jewish slaves was emphasized in the Middle Ages yet Jews continued to own Jewish slaves, and owners were able to bequeath Jewish slaves to the owner's children, but Jewish slaves were treated in many ways like members of the owner's family.

Redeeming Jewish slaves

The Hebrew Bible contains instructions to redeem (purchase the freedom of) Jewish slaves owned by non-Jews (Lev. 25:47-51). Following the suppression of the 66AD rebellion in Judea by the Roman army, many Jews were taken to Rome as prisoners of war. In response, the Talmud contained guidance to emancipate Jewish slaves, but cautioned the redeemer against paying excessive prices since that may encourage Roman captors to enslave more Jews. Josephus, himself a former 1st century slave, remarks that the faithfulness of Jewish slaves was appreciated by their owners; this may have been one of the main reasons for freeing them.

In the Middle Ages, redeeming Jewish slaves gained importance and—up until the 19th century—Jewish congregations around the Mediterranean Sea formed societies dedicated to that purpose. Jewish communities customarily ransomed Jewish captives according to a Judaic mitzvah regarding the redemption of captives (Pidyon Shvuyim). In his A History of the Jews, Paul Johnson wrote, "Jews were particularly valued as captives since it was believed, usually correctly, that even if they themselves poor, a Jewish community somewhere could be persuaded to ransom them. ... In Venice, the Jewish Levantine and Portuguese congregations set up a special organization for redeeming Jewish captives taken by Christians from Turkish ships, Jewish merchants paid a special tax on all goods to support it, which acted as a form of insurance since they were likely victims."

Modern era

Latin America and the Caribbean

Some Jews participated in the European colonization of the Americas, and owned black slaves in Latin America and the Caribbean, most notably in Brazil and Suriname, but also in Barbados and Jamaica. Especially in Suriname, Jews owned many large plantations.

Mediterranean slave trade

The Jews of Algiers were frequent purchasers of Christian slaves from Barbary corsairs. Meanwhile, Jewish brokers in Livorno, Italy, were instrumental in arranging the ransom of Christian slaves from Algiers to their home countries and freedom. Although one slave accused Livorno's Jewish brokers of holding the ransom until the captives died, this allegation is uncorroborated, and other reports indicate Jews as being very active in assisting the release of English Christian captives. In 1637, an exceptionally poor year for ransoming captives, the few slaves freed were ransomed largely by Jewish factors in Algiers working with Henry Draper.

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade transferred African slaves from Africa to colonies in the New World. Much of the slave trade followed a triangular route: slaves were transported from Africa to the Caribbean, sugar from there to North America or Europe, and manufactured goods from there to Africa. Jews and descendants of Jews participated in the slave trade on both sides of the Atlantic, in the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal on the eastern side, and in Brazil, Caribbean, and North America on the west side.

After Spain and Portugal expelled many of their Jewish residents in the 1490s, many Jews from Spain and Portugal migrated to the Americas and to the Netherlands. Jewish participation in the Atlantic slave trade increased through the 17th century because Spain and Portugal maintained a dominant role in the Atlantic trade and peaked in the early 18th century, but started to decline after the British "emerged with the asiento [permission to sell slaves in Spanish possessions] at the Peace of Utrecht in 1713", and Spain and Portugal soon became superseded by Northern European merchants in participation in the slave trade. By the height of the Atlantic slave trade in the 18th century (spurred on in part due to increasing European demands for sugar), Jewish participation was minimised as the Northern European nations which held colonies in the Americas often refused to allow Jews among their number. Despite this, some Jewish immigrants to the Thirteen Colonies owned slaves on plantations in the Southern colonies.

Brazil

The role of Jewish converts to Christianity (New Christians) and of Jewish traders was momentarily significant in Brazil and the Christian inhabitants of Brazil were envious because the Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco, and some Jews were among the leading slave traders in the colony. Some Jews from Brazil migrated to Rhode Island in the American colonies, and played a significant but non dominant role in the 18th-century slave trade of that colony; this sector accounted for only a very tiny portion of the total human exports from Africa.

Caribbean and Suriname

The New World location where Jews played the largest role in the slave-trade was in the Caribbean and Suriname, most notably in possessions of the Netherlands, that were serviced by the Dutch West India Company. The slave trade was one of the most important occupations of Jews living in Suriname and the Caribbean. The Jews of Suriname were the largest slave-holders in the region.

According to Austen, "the only places where Jews came close to dominating the New World plantation systems were Curaçao and Suriname." Slave auctions in the Dutch colonies were postponed if they fell on a Jewish holiday. Jewish merchants in the Dutch colonies acted as middlemen, buying slaves from the Dutch West India Company, and reselling them to plantation owners. The majority of buyers at slave auctions in the Brazil and the Dutch colonies were Jews. Jews allegedly played a "major role" in the slave trade in Barbados and Jamaica, and Jewish plantation owners in Suriname helped suppress several slave revolts between 1690 to 1722.

In Curaçao, Jews were involved in trading slaves, although at a far lesser extent compared to the Protestants of the island. Jews imported fewer than 1,000 slaves to Curaçao between 1686 and 1710, after which the slave trade diminished. Between 1630 and 1770, Jewish merchants settled or handled "at least 15,000 slaves" who landed in Curaçao, about one-sixth of the total Dutch slave trade.

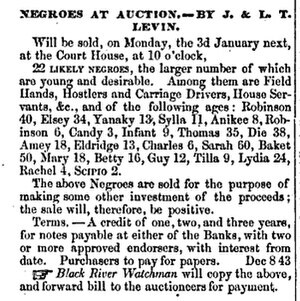

North American colonies

The Jewish role in the American slave trade was minimal. According to historian and rabbi Bertram Korn, there were Jewish owners of plantations, but altogether they constituted only a tiny proportion of the industry. In 1830 there were only four Jews among the 11,000 Southerners who owned fifty or more slaves.

Of all the shipping ports in Colonial America, only in Newport, Rhode Island, did Jewish merchants play a significant part in the slave-trade.

A table of the commissions of brokers in Charleston, South Carolina, shows that one Jewish brokerage accounted for 4% of the commissions. According to Bertram Korn, Jews accounted for 4 of the 44 slave-brokers in Charleston, three of 70 in Richmond, and 1 of 12 in Memphis. However the proportion of Jewish residents of Charleston who owned slaves was similar to that of the general white population (83% versus 87% in 1830).

Assessing the extent of Jewish involvement in the Atlantic slave trade

Historian Seymour Drescher emphasized the problems of determining whether or not slave-traders were Jewish. He concludes that New Christian merchants managed to gain control of a sizeable share of all segments of the Portuguese Atlantic slave trade during the Iberian-dominated phase of the Atlantic system. Due to forcible conversions of Jews to Christianity many New Christians continued to practice Judaism in secret, meaning it is impossible for historians to determine what portion of these slave traders were Jewish, because to do so would require the historian to choose one of several definitions of "Jewish".

The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews (book)

In 1991, the Nation of Islam (NOI) published The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, which alleged that Jews had dominated the Atlantic slave trade. Volume 1 of the book claims Jews played a major role in the Atlantic slave trade, and profited from slavery. The book was heavily criticized for being anti-Semitic, and for failing to provide any objective analysis of the role of Jews in the slave trade. Common criticisms included the book's selective quotations, "crude use of statistics", and was purposefully trying to exaggerate the role of Jews. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) criticized the NOI and the book. Henry Louis Gates Jr. criticized the book's intention and scholarship.

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

Historian Ralph A. Austen heavily criticized the book and said that although the book may seem fairly accurate, it is an anti-Semitic book. However, he added that before the publication of The Secret Relationship, some scholars were reluctant to discuss Jewish involvement in slavery because of fear of damaging the "shared liberal agenda" of Jews and African Americans. In that sense, Austen found the book's aims of challenging the myth of universal Jewish benevolence throughout history to be legitimate even though the means to that end resulted in an anti-Semitic book.

Later assessments

The publication of The Secret Relationship spurred detailed research into the participation of Jews in the Atlantic slave trade, resulting in the publication of the following works, most of which were published specifically to refute the thesis of The Secret Relationship:

- 1992 – Harold Brackman, Jew on the brain: A public refutation of the Nation of Islam's The Secret relationship between Blacks and Jews

- 1992 – David Brion Davis, "Jews in the Slave Trade", in Culturefront (Fall 1 992), pp. 42–45

- 1993 – Seymour Drescher, "The Role of Jews in the Atlantic Slave Trade", Immigrants and Minorities, 12 (1993), pp. 113–25

- 1993 – Marc Caplan, Jew-Hatred As History: An Analysis of the Nation of Islam's "The Secret Relationship" (published by the Anti Defamation League)

- 1998 – Eli Faber, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight, New York University Press

- 1999 – Saul S. Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade, Transaction

Most post-1991 scholars that analysed the role of Jews only identified certain regions (such as Brazil and the Caribbean) where the participation was "significant". Wim Klooster wrote: "In no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades. They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every British territory in North America and the Caribbean. Even when Jews in a handful of places owned slaves in proportions slightly above their representation among a town's families, such cases do not come close to corroborating the assertions of The Secret Relationship".

David Brion Davis wrote that "Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery." Jacob R. Marcus wrote that Jewish participation in the American Colonies was "minimal" and inconsistent. Bertram Korn wrote "all of the Jewish slavetraders in all of the Southern cities and towns combined did not buy and sell as many slaves as did the firm of Franklin and Armfield, the largest Negro traders in the South."

According to a review in The Journal of American History of both Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight and Jews and the American Slave Trade: "Faber acknowledges the few merchants of Jewish background locally prominent in slaving during the second half of the eighteenth century but otherwise confirms the small-to-minuscule size of colonial Jewish communities of any sort and shows them engaged in slaving and slave holding only to degrees indistinguishable from those of their English competitors."

According to Seymour Drescher, Jews participated in the Atlantic slave trade, particularly in Brazil and Suriname, however "in no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades" (Wim Klooster). He said that Jews rarely established new slave-trading routes, but rather worked in conjunction with a Christian partner, on trade routes that had been established by Christians and endorsed by Christian leaders of nations. In 1995 the American Historical Association (AHA) issued a statement, together with Drescher, condemning "any statement alleging that Jews played a disproportionate role in the Atlantic slave trade".

According to a review in The Journal of American History of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight (Faber) and Jews and the American Slave Trade (Friedman), "Eli Faber takes a quantitative approach to Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade in Britain's Atlantic empire, starting with the arrival of Sephardic Jews in the London resettlement of the 1650s, calculating their participation in the trading companies of the late seventeenth century, and then using a solid range of standard quantitative sources (Naval Office shipping lists, censuses, tax records, and so on) to assess the prominence in slaving and slave owning of merchants and planters identifiable as Jewish in Barbados, Jamaica, New York, Newport, Philadelphia, Charleston, and all other smaller English colonial ports." Historian Ralph Austen, however, acknowledges "Sephardi Jews in the New World had been heavily involved in the African slave trade."

Jewish slave ownership in the southern United States

Slavery historian Jason H. Silverman describes the part of Jews in slave trading in the southern United states as "minuscule", and wrote that the historical rise and fall of slavery in the United States would not have been affected at all had there been no Jews living in the south. Jews accounted for only 1.25% of all Southern slave owners.

Jewish slave ownership practices in the Southern United States were governed by regional practices, rather than Judaic law. Jews conformed to the prevailing patterns of slave ownership in the South, and were not significantly different from other slave owners in their treatment of slaves. Wealthy Jewish families in the American South generally preferred employing white servants rather than owning slaves. Jewish slave owners included Aaron Lopez, Francis Salvador, Judah Touro, and Haym Salomon.

Jewish slave owners were found mostly in business or domestic settings, rather than on plantations, so most of the slave ownership was in an urban context — running a business or as domestic servants. Jewish slave owners freed their black slaves at about the same rate as non-Jewish slave owners. Jewish slave owners sometimes bequeathed slaves to their children in their wills.

Abolition debate

A significant number of Jews gave their energies to the antislavery movement. Many 19th century Jews, such as Adolphe Crémieux, participated in the moral outcry against slavery. In 1849, Crémieux announced the abolition of slavery throughout the French possessions.

In Britain, there were Jewish members of the abolition groups. Granville Sharp and Wilberforce, in his "A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade," employed Jewish teachings as arguments against slavery. Rabbi G. Gottheil of Manchester, and Dr. L. Philippson of Bonn and Magdeburg, forcibly combated the view announced by Southern sympathizers that Judaism supports slavery. Rabbi M. Mielziner's anti-slavery work "Die Verhältnisse der Sklaverei bei den Alten Hebräern", published in 1859, was translated and published in the United States as "Slavery Among Hebrews". Similarly, in Germany, Berthold Auerbach in his fictional work "Das Landhaus am Rhein" aroused public opinion against slavery and the slave trade, and Heinrich Heine also spoke against slavery. Immigrant Jews were among abolitionist John Brown's band of antislavery fighters in Kansas, including Theodore Wiener (from Poland); Jacob Benjamin (from Bohemia), and August Bondi (1833-1907) from Vienna. Nathan Meyer Rothschild was known for his role in the British abolition of the slave trade through his partial financing of the £20 million British government compensation paid to former owners of the freed slaves.

A Jewish woman, Ernestine Rose, was called "queen of the platforms" in the 19th century because of her speeches in favor of abolition. Her lectures were met with controversy. Her most ill-received appearance was likely in Charleston, Virginia (today West Virginia), where her lecture on the evils of slavery was met with such vehement opposition and outrage that she was forced to exercise considerable influence to even get out of the city safely.

Pro-slavery Jews

See also Jewish Confederates

In the Civil War era, prominent Jewish religious leaders in the United States engaged in public debates about slavery. Generally, rabbis from the Southern states supported slavery, and those from the North opposed slavery.

However, in 1861, the Charlotte Evening Bulletin noted: "It is a singular fact that the most masterly expositions which have lately been made of the constitutional and the religious argument for slavery are from gentlemen of the Hebrew faith". After referring to the speech of Judah Benjamin, the "most unanswerable speech on the rights of the South ever made in the Senate", it refers to the lecture of Rabbi Raphall, "a discourse which stands like the tallest peak of the Himmalohs [sic]—immovable and incomparable".

The most notable debate was between Rabbi Morris Jacob Raphall, who defended slavery as it was practiced in the South because slavery was endorsed by the Bible, and rabbi David Einhorn, who opposed its current form. However, there were not many Jews in the South, and Jews accounted for only 1.25% of all Southern slave owners. In 1861, Raphall published his views in a treatise called "The Bible View of Slavery". Raphall and other pro-slavery rabbis such as Isaac Leeser and J. M. Michelbacher (both of Virginia), used the Tanakh (Jewish Bible) to support their arguments.

Abolitionist rabbis, including Einhorn and Michael Heilprin, concerned that Raphall's position would be seen as the official policy of American Judaism, vigorously rebutted his arguments, and argued that slavery – as practiced in the South – was immoral and not endorsed by Judaism.

Ken Yellis, writing in The Forward, has suggested that "the majority of American Jews were mute on the subject, perhaps because they dreaded its tremendous corrosive power. Prior to 1861, there are virtually no instances of rabbinical sermons on slavery, probably due to fear that the controversy would trigger a sectional conflict in which Jewish families would be arrayed on opposite sides. ... America's largest Jewish community, New York's Jews, were overwhelmingly pro-southern, pro-slavery, and anti-Lincoln in the early years of the war." However, as the war progressed, "and the North's military victories mounted, feelings began to shift toward[s] ... the Union and eventually, emancipation."

Contemporary times

In contemporary affairs, Jews and African-Americans have cooperated in the Civil Rights Movement, motivated partially by the common background of slavery, particularly the story of the Jewish enslavement in Egypt, as told in the Biblical story of the Book of Exodus, which many blacks identified with. Seymour Siegel suggests that the historic struggle against prejudice faced by Jews led to a natural sympathy for any people confronting discrimination. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, spoke from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial during the famous March on Washington in 1963 where he emphasized how Jews identify deeply with African American disenfranchisement "born of our own painful historic experience," including slavery and ghettoization.

Presently, according to the Orthodox Union, The Forward, and the Jewish Quarterly, slavery (as defined as the total subjugation of one human being over another) is absolutely unacceptable in Judaism.