Anarchy is a society being freely constituted without authorities or a governing body. It may also refer to a society or group of people that entirely rejects a set hierarchy. Anarchy was first used in English in 1539, meaning "an absence of government". Pierre-Joseph Proudhon adopted anarchy and anarchist in his 1840 treatise What Is Property? to refer to anarchism, a new political philosophy and social movement that advocates stateless societies based on free and voluntary associations. Anarchists seek a system based on the abolition of all coercive hierarchy, in particular the state, and many advocate for the creation of a system of direct democracy and worker cooperatives.

In practical terms, anarchy can refer to the curtailment or abolition of traditional forms of government and institutions. It can also designate a nation or any inhabited place that has no system of government or central rule. Anarchy is primarily advocated by individual anarchists who propose replacing government with voluntary institutions. These institutions or free associations are generally modeled on nature since they can represent concepts such as community and economic self-reliance, interdependence, or individualism. Although anarchy is often negatively used as a synonym of chaos or societal collapse, this is not the meaning that anarchists attribute to anarchy, a society without hierarchies. Proudhon wrote that anarchy is "Not the Daughter But the Mother of Order."

Etymology

Anarchy comes from the Medieval Latin anarchia and from the Greek anarchos ("having no ruler"), with an + archos ("ruler") literally meaning "without ruler". The circle-A anarchist symbol is a monogram that consists of the capital letter A surrounded by the capital letter O. The letter A is derived from the first letter of anarchy or anarchism in most European languages and is the same in both Latin and Cyrillic scripts. The O stands for order and together they stand for "society seeks order in anarchy" (French: la société cherche l'ordre dans l'anarchie), a phrase written by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his 1840 book What Is Property?

Overview

Anthropology

Although most known societies are characterized by the presence of hierarchy or the state, anthropologists have studied many egalitarian stateless societies, including most nomadic hunter-gatherer societies and horticultural societies such as the Semai and the Piaroa. Many of these societies can be considered to be anarchic in the sense that they explicitly reject the idea of centralized political authority.

The egalitarianism typical of human hunter-gatherers is interesting when viewed in an evolutionary context. One of humanity's two closest primate relatives, the chimpanzee, is anything but egalitarian, forming hierarchies that are dominated by alpha males. So great is the contrast with human hunter-gatherers that it is widely argued by palaeoanthropologists that resistance to being dominated was a key factor driving the development of human consciousness, language, kinship and social organization.

In Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, anarchist anthropologist David Graeber attempted to outline areas of research that intellectuals might explore in creating a cohesive body of anarchist social theory. Graeber posited that anthropology is "particularly well positioned" as an academic discipline that can look at the gamut of human societies and organizations to study, analyze and catalog alternative social and economic structures around the world, and most importantly, present these alternatives to the world.

In Society Against the State, Pierre Clastres examined stateless societies where certain cultural practices and attitudes avert the development of hierarchy and the state. Clastres dismissed the notion that the state is the natural outcome of the evolution of human societies.

In The Art of Not Being Governed, James C. Scott studied Zomia, a vast stateless upland region on Southeast Asia. The hills of Zomia isolate it from the lowland states and create a refuge for people to escape to. Scott argues that the particular social and cultural characteristics of the hill people were adapted to escape capture by the lowland states and should not be viewed as relics of barbarism abandoned by civilization.

Peter Leeson examined a variety of institutions of private law enforcement developed in anarchic situations by eighteenth century pirates, preliterate tribesmen, and Californian prison gangs. These groups all adapted different methods of private law enforcement to meet their specific needs and the particulars of their anarchic situation.

Anarcho-primitivists base their critique of civilization partly on anthropological studies of nomadic hunter-gatherers, noting that the shift towards domestication has likely caused increases in disease, labor, inequality, warfare and psychological disorders. Authors such as John Zerzan have argued that negative stereotypes of primitive societies (e.g. that they are typically extremely violent or impoverished) are used to justify the values of modern industrial society and to move individuals further away from more natural and equitable conditions.

International relations

In international relations, anarchy is "the absence of any authority superior to nation-states and capable of arbitrating their disputes and enforcing international law".

Political philosophy

Anarchism

As a political philosophy, anarchism advocates self-governed societies based on voluntary institutions. These are often described as stateless societies, although several authors have defined them more specifically as institutions based on non-hierarchical free associations. Anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, or harmful. While opposition to the state is central, it is a necessary but not sufficient condition, hence why, in spite of their names, anarcho-capitalism and national-anarchism are either not recognized as anarchist schools of thought and as part of the anarchist movement, or are seen by anarchists and scholars as fraudulent and an oxymoron. Anarchism entails opposing authority or hierarchical organisation in the conduct of all human relations, including yet not limited to the state system.

There are many types and traditions of anarchism, not all of which are mutually exclusive. Anarchist schools of thought can differ fundamentally, supporting anything from extreme individualism to complete collectivism. Strains of anarchism have been divided into the categories of individualist and social anarchism, or similar dual classifications. Anarchism is often considered to be a radical left-wing or far-left movement and much of anarchist economics and anarchist law reflect anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarian interpretations of left-wing and socialist politics such communism, mutualism and syndicalism, among other libertarian socialist and socialist economics such as collectivist anarchism, free-market anarchism, green anarchism and participatory economics. Within anarchism, some individualist anarchists are communists while some anarcho-communists are egoists or individualists. Where individualist forms of anarchism emphasize personal autonomy and the rational nature of human beings, social anarchism sees "individual freedom as conceptually connected with social equality and emphasize community and mutual aid". In European Socialism: A History of Ideas and Movements, Carl Landauer summarized the difference between communist and individualist anarchists by stating that "the communist anarchists also do not acknowledge any right to society to force the individual. They differ from the anarchistic individualists in their belief that men, if freed from coercion, will enter into voluntary associations of a communistic type, while the other wing believes that the free person will prefer a high degree of isolation".

As a social movement, anarchism has regularly endured fluctuations in popularity. The central tendency of anarchism as a mass social movement has been represented by anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism, with individualist anarchism being primarily a literary phenomenon while social anarchism has been the dominant form of anarchism, emerging in the late 19th century as a distinction from individualist anarchism after anarcho-communism replaced collectivist anarchism as the dominant tendency. Nonetheless, individualist anarchism did influence the bigger currents and individualists also participated in large anarchist organizations. Some anarchists are pacifists who support self-defense or non-violence (anarcho-pacifism) while others have supported the use of militant measures, including revolution and propaganda of the deed, on the path to an anarchist society.

Since the 1890s, libertarianism has been used as a synonym for anarchism and was used almost exclusively in this sense until the mid-20th century development of right-libertarianism in the United States, where classical liberals began to describe themselves as libertarians. It has since become necessary to distinguish their classical liberal individualist and free-market capitalist philosophy from anarchism. The former is often referred to as right-libertarianism whereas the latter is described by as left-libertarianism, libertarian socialism and socialist libertarianism. Examples of Right-libertarian ideologies include anarcho-capitalism, minarchism and voluntaryism. Outside the English-speaking world, libertarianism generally retains its association with anarchism, anti-capitalism, libertarian socialism and social anarchism.

Immanuel Kant

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant treated anarchy in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View as consisting of "Law and Freedom without Force". For Kant, anarchy falls short of being a true civil state because the law is only an "empty recommendation" if force is not included to make this law efficacious ("legitimation", etymologically fancifully from legem timere, i.e. "fearing the law"). For there to be such a state, force must be included while law and freedom are maintained, a state which Kant calls a republic. Kant identified four kinds of government:

- Law and freedom without force (anarchy)

- Law and force without freedom (despotism)

- Force without freedom and law (barbarism)

- Force with freedom and law (republic)

Examples of state-collapse anarchy

English Civil War (1642–1651)

Anarchy was one of the issues at the Putney Debates of 1647:

Thomas Rainsborough: "I shall now be a little more free and open with you than I was before. I wish we were all true-hearted, and that we did all carry ourselves with integrity. If I did mistrust you I would not use such asseverations. I think it doth go on mistrust, and things are thought too readily matters of reflection, that were never intended. For my part, as I think, you forgot something that was in my speech, and you do not only yourselves believe that some men believe that the government is never correct, but you hate all men that believe that. And, sir, to say because a man pleads that every man hath a voice by right of nature, that therefore it destroys by the same argument all property – this is to forget the Law of God. That there's a property, the Law of God says it; else why hath God made that law, Thou shalt not steal? I am a poor man, therefore I must be oppressed: if I have no interest in the kingdom, I must suffer by all their laws be they right or wrong. Nay thus: a gentleman lives in a country and hath three or four lordships, as some men have (God knows how they got them); and when a Parliament is called he must be a Parliament-man; and it may be he sees some poor men, they live near this man, he can crush them – I have known an invasion to make sure he hath turned the poor men out of doors; and I would fain know whether the potency of rich men do not this, and so keep them under the greatest tyranny that was ever thought of in the world. And therefore I think that to that it is fully answered: God hath set down that thing as to propriety with this law of his, Thou shalt not steal. And for my part I am against any such thought, and, as for yourselves, I wish you would not make the world believe that we are for anarchy."

Oliver Cromwell: "I know nothing but this, that they that are the most yielding have the greatest wisdom; but really, sir, this is not right as it should be. No man says that you have a mind to anarchy, but that the consequence of this rule tends to anarchy, must end in anarchy; for where is there any bound or limit set if you take away this limit, that men that have no interest but the interest of breathing shall have no voice in elections? Therefore, I am confident on’t, we should not be so hot one with another."

As people began to theorize about the English Civil War, anarchy came to be more sharply defined, albeit from differing political perspectives:

- 1651 – Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan) describes the natural condition of mankind as a war of all against all, where man lives a brutish existence: "For the savage people in many places of America, except the government of small families, the concord whereof dependeth on natural lust, have no government at all, and live at this day in that brutish manner". Hobbes finds three basic causes of the conflict in this state of nature, namely competition, diffidence and glory: "The first maketh men invade for gain; the second, for safety; and the third, for reputation". His first law of nature is that "every man ought to endeavour peace, as far as he has hope of obtaining it; and when he cannot obtain it, that he may seek and use all helps and advantages of war". In the state of nature, "every man has a right to every thing, even to then go for one another's body", but the second law is that in order to secure the advantages of peace "that a man be willing, when others are so too ... to lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men as he would allow other men against himself". This is the beginning of contracts/covenants; performing of which is the third law of nature. Therefore, injustice is failure to perform in a covenant and all else is just.

- 1656 – James Harrington (The Commonwealth of Oceana) uses anarchy to describe a situation where the people use force to impose a government on an economic base composed of either solitary land ownership (absolute monarchy), or land in the ownership of a few (mixed monarchy). He distinguishes it from commonwealth, the situation when both land ownership and governance shared by the population at large, seeing it as a temporary situation arising from an imbalance between the form of government and the form of property relations.

French Revolution (1789–1799)

Thomas Carlyle, Scottish essayist of the Victorian era known foremost for his widely influential work of history, The French Revolution, wrote that the French Revolution was a war against both aristocracy and anarchy:

Meanwhile, we will hate Anarchy as Death, which it is; and the things worse than Anarchy shall be hated more! Surely Peace alone is fruitful. Anarchy is destruction: a burning up, say, of Shams and Insupportabilities; but which leaves Vacancy behind. Know this also, that out of a world of Unwise nothing but an Unwisdom can be made. Arrange it, Constitution-build it, sift it through Ballot-Boxes as thou wilt, it is and remains an Unwisdom,-- the new prey of new quacks and unclean things, the latter end of it slightly better than the beginning. Who can bring a wise thing out of men unwise? Not one. And so Vacancy and general Abolition having come for this France, what can Anarchy do more? Let there be Order, were it under the Soldier's Sword; let there be Peace, that the bounty of the Heavens be not spilt; that what of Wisdom they do send us bring fruit in its season! – It remains to be seen how the quellers of Sansculottism were themselves quelled, and sacred right of Insurrection was blown away by gunpowder: wherewith this singular eventful History called French Revolution ends.

In 1789, Armand, duc d'Aiguillon came before the National Assembly and shared his views on the anarchy:

I may be permitted here to express my personal opinion. I shall no doubt not be accused of not loving liberty, but I know that not all movements of peoples lead to liberty. But I know that great anarchy quickly leads to great exhaustion and that despotism, which is a kind of rest, has almost always been the necessary result of great anarchy. It is therefore much more important than we think to end the disorder under which we suffer. If we can achieve this only through the use of force by authorities, then it would be thoughtless to keep refraining from using such force.

Armand was later exiled because he was viewed as being opposed to the revolution's violent tactics. Professor Chris Bossche commented on the role of anarchy in the revolution:

In The French Revolution, the narrative of increasing anarchy undermined the narrative in which the revolutionaries were striving to create a new social order by writing a constitution.

Jamaica (1720)

In 1720, Sir Nicholas Lawes, Governor of Jamaica, wrote to John Robinson, the Bishop of London:

As to the Englishmen that came as mechanics hither, very young and have now acquired good estates in Sugar Plantations and Indigo & co., of course they know no better than what maxims they learn in the Country. To be now short & plain Your Lordship will see that they have no maxims of Church and State but what are absolutely anarchical.

In the letter, Lawes goes on to complain that these "estated men now are like Jonah's gourd" and details the humble origins of the "creolians" largely lacking an education and flouting the rules of church and state. In particular, he cites their refusal to abide by the Deficiency Act which required slave owners to procure from England one white person for every 40 enslaved Africans, thereby hoping to expand their own estates and inhibit further English/Irish immigration. Lawes describes the government as being "anarchical, but nearest to any form of Aristocracy", further arguing: "Must the King's good subjects at home who are as capable to begin plantations, as their Fathers, and themselves were, be excluded from their Liberty of settling Plantations in this noble Island, for ever and the King and Nation at home be deprived of so much riches, to make a few upstart Gentlemen Princes?"

Albania (1997)

In 1997, Albania fell into a state of anarchy, mainly due to the heavy losses of money caused by the collapse of pyramid firms. As a result of the societal collapse, heavily armed criminals roamed freely with near total impunity. There were often 3–4 gangs per city, especially in the south, where the police did not have sufficient resources to deal with gang-related crime.

Somalia (1991–2006)

Following the outbreak of the civil war in Somalia and the ensuing collapse of the central government, residents reverted to local forms of conflict resolution, either secular, traditional or Islamic law, with a provision for appeal of all sentences. The legal structure in the country was divided along three lines, namely civil law, religious law and customary law (xeer).

While Somalia's formal judicial system was largely destroyed after the fall of the Siad Barre regime, it was later gradually rebuilt and administered under different regional governments such as the autonomous Puntland and Somaliland macro-regions. In the case of the Transitional National Government and its successor the Transitional Federal Government, new interim judicial structures were formed through various international conferences. Despite some significant political differences between them, all of these administrations shared similar legal structures, much of which were predicated on the judicial systems of previous Somali administrations. These similarities in civil law included a charter which affirms the primacy of Muslim shari'a or religious law, although in practice shari'a is applied mainly to matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance and civil issues. The charter assured the independence of the judiciary which in turn was protected by a judicial committee; a three-tier judicial system including a supreme court, a court of appeals and courts of first instance (either divided between district and regional courts, or a single court per region); and the laws of the civilian government which were in effect prior to the military coup d'état that saw the Barre regime into power remain in forced until the laws are amended.

Economist Alex Tabarrok claimed that Somalia in its stateless period provided a "unique test of the theory of anarchy", in some aspects near of that espoused by anarcho-capitalists such as David D. Friedman and Murray Rothbard. Nonetheless, both anarchists and some anarcho-capitalists such as Walter Block argue that Somalia was not an anarchist society.

Anarchist movements

Russian Civil War (1917–1922)

During the Russian Civil War which initially started as a confrontation between the Bolsheviks and monarchists, on the territory of today's Ukraine a new force emerged, namely the Anarchist Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine led by Nestor Makhno. The Ukrainian Anarchist during the Russian Civil War (also called the Black Army) organized the Free Territory, an anarchist society committed to resisting state authority, whether capitalist or communist. This project was cut short by the consolidation of Bolshevik power. Makhno was described by anarchist theorist Emma Goldman as "an extraordinary figure" leading a revolutionary peasants' movement.

During 1918, most of Ukraine was controlled by the forces of the Central Powers which were unpopular among the people. In March 1918, the young anarchist Makhno's forces and allied anarchist and guerrilla groups won victories against German, Austrian and Ukrainian nationalist (the army of Symon Petlura) forces and units of the White Army, capturing a lot of German and Austro-Hungarian arms. These victories over much larger enemy forces established Makhno's reputation as a military tactician and became known as Batko ("Father") to his admirers.

Makhno called the Bolsheviks dictators and opposed the "Cheka [secret police] ... and similar compulsory authoritative and disciplinary institutions" and called for "[f]reedom of speech, press, assembly, unions and the like". The Bolsheviks accused the Makhnovists of imposing a formal government over the area they controlled and also said that Makhnovists used forced conscription, committed summary executions and had two military and counter-intelligence forces, namely the Razvedka and the Kommissiya Protivmakhnovskikh Del (patterned after the Cheka and the GRU). However, later historians have dismissed these claims as fraudulent propaganda.

Spain (1936)

In 1936, the Spanish general Francisco Franco lead coup d'état aimed at overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic to establishing totalitarianism. At that time, the government of the Republic was in no position to stop the falangist coup. However, the first resistance to mobilize were anarchist trade unions which organized a general strike and created militias.

Given that power was in the hands of the trade unions, particularly the CNT, they began to establish anarchism in what was the Spanish Revolution of 1936. This was a social revolution as much as a political revolution. Throughout the war and shortly after, many Spanish working-class citizens lived in anarchist communities, many of which thrived during this time.

However, the government of the Spanish Republic and the Communist Party of Spain began to regain power through support from the Soviet Union. There was a divide between those that wanted to use the revolution as a force to undermine the Falangists by causing uprisings behind their lines and those that wanted to fight a traditional war using the government-controlled Popular Front. In the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin and the Communist International (Comintern) which he led, was in favor of the popular front approach. Desperate to defeat the Falangists, who were getting support from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the government of the Spanish Republic and the Communist Party of Spain decided to seize back control from the anarchist unions and crush most of the revolution in what became known as the May Days of 1937.

Eventually, the popular front approach would not work, as the Nationalists won the war and set up a military dictatorship led by Franco, ending the last of the remaining anarchist communes.

Lists of ungoverned communities

Ungoverned communities

- Zomia, Southeast Asian highlands beyond control of governments

- Republic of Cospaia (1440–1826)

- Anarchy in the United States (19th century)

- Diggers (England; 1649–1651)

- Libertatia (late 17th century)

- Neutral Moresnet (26 June 1816 – 28 June 1919)

- Kowloon Walled City, a largely ungoverned squatter settlement from the mid-1940s until the early 1970s

- Drop City, the first rural hippie commune (Colorado; 1965–1977)

- Comunidades de Población en Resistencia (CPR), indigenous movement (Guatemala; 1988–present)

- Slab City, squatted RV desert community (California; 1965–present)

- Abahlali baseMjondolo, a South African social movement (2005–present)

- Ras Khamis

- Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (Seattle; 2020)

Anarchist communities

Anarchists have been involved in a wide variety of communities. While there are only a few instances of mass society anarchies that have come about from explicitly anarchist revolutions, there are also examples of intentional communities founded by anarchists.

- Intentional communities

- Utopia, Ohio (1847)

- Whiteway Colony (1898)

- Kibbutz (1909–present)

- Life and Labor Commune (1921)

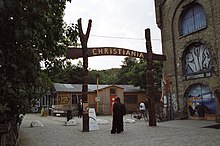

- Freetown Christiania (26 September 1971–present)

- Trumbullplex (1993–present)

- Mass societies

- Free Territory (Ukraine; November 1918 – 1921)

- Revolutionary Catalonia (21 July 1936 – May 1939)

- Shinmin Prefecture (1929–1931)

- Federation of Neighborhood Councils-El Alto (Fejuve; 1979–present)

- Rebel Autonomous Zapatista Municipalities (MAREZ; 1994–present)

- Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (Rojava; 2012–present)