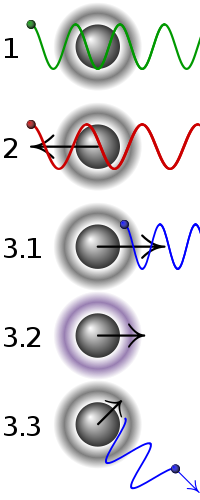

| 1 | A stationary atom sees the laser neither red- nor blue-shifted and does not absorb the photon. |

|---|---|

| 2 | An atom moving away from the laser sees it red-shifted and does not absorb the photon. |

| 3.1 | An atom moving towards the laser sees it blue-shifted and absorbs the photon, slowing the atom. |

| 3.2 | The photon excites the atom, moving an electron to a higher quantum state. |

| 3.3 | The atom re-emits a photon. As its direction is random, there is no net change in momentum over many absorption-emission cycles. |

In condensed matter physics, laser cooling includes a number of techniques in which atoms, molecules, and small mechanical systems are cooled, often approaching temperatures near absolute zero. Laser cooling techniques rely on the fact that when an object (usually an atom) absorbs and re-emits a photon (a particle of light) its momentum changes. For an ensemble of particles, their thermodynamic temperature is proportional to the variance in their velocity. That is, more homogeneous velocities among particles corresponds to a lower temperature. Laser cooling techniques combine atomic spectroscopy with the aforementioned mechanical effect of light to compress the velocity distribution of an ensemble of particles, thereby cooling the particles.

The 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, Steven Chu, and William Daniel Phillips "for development of methods to cool and trap atoms with laser light".

History

Radiation pressure

Radiation pressure is the force that electromagnetic radiation exerts on matter. In 1873 Maxwell published his treatise on electromagnetism in which he predicted radiation pressure. The force was experimentally demonstrated for the first time by Lebedev and reported at a conference in Paris in 1900, and later published in more detail in 1901. Following Lebedev's measurements Nichols and Hull also demonstrated the force of radiation pressure in 1901, with a refined measurement reported in 1903.

In 1933, Otto Frisch deflected an atomic beam of sodium atoms with light. This was the first realization of radiation pressure acting on a resonant transition.

Laser cooling proposals

The introduction of lasers in atomic manipulation experiments acted as the advent of laser cooling proposals in the mid 1970s. Laser cooling was proposed separately in 1975 by two different research groups: Hänsch and Schawlow, and Wineland and Dehmelt. Both proposals outlined a process of slowing heat-based velocity in atoms with "radiative forces." In the paper by Hänsch and Schawlow, the effect of radiation pressure on any object that reflects light is described. That concept was then connected to the cooling of atoms in a gas. These early proposals for laser cooling only relied on "scattering force", the name for the radiation pressure.

In the late 1970s, Ashkin described how radiation forces can be used to simultaneously cool and trap atoms. He emphasized how this process could allow for long spectroscopic measurements without the atoms escaping the trap and proposed the overlapping of optical traps in order to study interactions between different atoms.

Initial realizations

Closely following Ashkin's letter in 1978, two research groups: Wineland, Drullinger and Walls, and Neuhauser, Hohenstatt, Toscheck and Dehmelt further refined that work. In specific, Wineland, Drullinger, and Walls were concerned with the improvement of spectroscopy. The group wrote about experimentally demonstrating the cooling of atoms through a process using radiation pressure. They cite a precedence for using radiation pressure in optical traps, yet criticize the ineffectiveness of previous models due to the presence of the Doppler effect. In an effort to lessen the effect, they applied an alternative take on cooling magnesium ions below the room temperature precedent. Using the electromagnetic trap to contain the magnesium ions, they bombarded them with a laser barely out of phase from the resonant frequency of the atoms. The research from both groups served to illustrate the mechanical properties of light. Around this time, laser cooling techniques had allowed for temperatures lowered to around 40 kelvins.

William Phillips was influenced by the Wineland paper and attempted to mimic it, using neutral atoms instead of ions. In 1982, he published the first paper outlining the cooling of neutral atoms. The process he used is now known as the Zeeman slower and became one of the standard techniques for slowing an atomic beam.

Modern advances

Atoms

Now, temperatures around 240 microkelvins were reached. That threshold was the lowest researchers thought was possible. When temperatures then reached 43 microkelvins in an experiment by Steven Chu, the new low was explained by the addition of more atomic states in combination to laser polarization. Previous conceptions of laser cooling were decided to have been too simplistic. The major breakthroughs in the 70s and 80s in the use of laser light for cooling led to several improvements to preexisting technology and new discoveries with temperatures just above absolute zero. The cooling processes were utilized to make atomic clocks more accurate and to improve spectroscopic measurements, and led to the observation of a new state of matter at ultracold temperatures. The new state of matter, the Bose–Einstein condensate, was observed in 1995 by Eric Cornell, Carl Wieman, and Wolfgang Ketterle.

Laser cooling was primarily used to create ultracold atoms. For example, the experiments in quantum physics need to perform near absolute zero where unique quantum effects such as Bose–Einstein condensation can be observed. Laser cooling is also a primary tool in optical clock experiments. Laser cooling has primarily been used on atoms, but recent progress has been made toward laser cooling more complex systems. For example, a team at UT Austin demonstrated the use of laser cooling for noninvasive optical trapping and manipulation, a technique they termed opto-refrigerative tweezers.

Molecules

In 2010, a team at Yale successfully laser-cooled a diatomic molecule. In 2016, a group at MPQ successfully cooled formaldehyde to 420 μK via optoelectric Sisyphus cooling. In 2022, a group at Harvard successfully trapped and laser cooled CaOH to a minimum temperature of 720(40) μK in a magneto-optical trap.

Mechanical systems

In 2007, an MIT team successfully laser-cooled a macro-scale (1 gram) object to 0.8 K. In 2011, a team from the California Institute of Technology and the University of Vienna became the first to laser-cool a (10 μm x 1 μm) mechanical object to its quantum ground state.

Methods

The first example of laser cooling, and also still the most common method (so much so that it is still often referred to simply as 'laser cooling') is Doppler cooling.

Doppler cooling

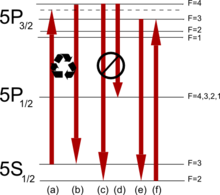

Doppler cooling, which is usually accompanied by a magnetic trapping force to give a magneto-optical trap, is by far the most common method of laser cooling. It is used to cool low density gases down to the Doppler cooling limit, which for rubidium-85 is around 150 microkelvins.

In Doppler cooling, initially, the frequency of light is tuned slightly below an electronic transition in the atom. Because the light is detuned to the "red" (i.e., at lower frequency) of the transition, the atoms will absorb more photons if they move towards the light source, due to the Doppler effect. Thus if one applies light from two opposite directions, the atoms will always scatter more photons from the laser beam pointing opposite to their direction of motion. In each scattering event the atom loses a momentum equal to the momentum of the photon. If the atom, which is now in the excited state, then emits a photon spontaneously, it will be kicked by the same amount of momentum, but in a random direction. Since the initial momentum change is a pure loss (opposing the direction of motion), while the subsequent change is random, the probable result of the absorption and emission process is to reduce the momentum of the atom, and therefore its speed—provided its initial speed was larger than the recoil speed from scattering a single photon. If the absorption and emission are repeated many times, the average speed, and therefore the kinetic energy of the atom, will be reduced. Since the temperature of a group of atoms is a measure of the average random internal kinetic energy, this is equivalent to cooling the atoms.

Anti-Stokes cooling

The idea for anti-Stokes cooling was first advanced by Pringsheim in 1929. While Doppler cooling lowers the translational temperature of a sample, anti-Stokes cooling decreases the vibrational or phonon excitation of a medium. This is accomplished by pumping a substance with a laser beam from a low-lying energy state to a higher one with subsequent emission to an even lower-lying energy state. The principal condition for efficient cooling is that the anti-Stokes emission rate to the final state be significantly larger than that to other states as well as the nonradiative relaxation rate. Because vibrational or phonon energy can be many orders of magnitude larger than the energy associated with Doppler broadening, the efficiency of heat removal per laser photon expended for anti-Stokes cooling can be correspondingly larger than that for Doppler cooling. The anti-Stokes cooling effect was first demonstrated by Djeu and Whitney in CO2 gas. The first anti-Stokes cooling in a solid was demonstrated by Epstein et al. in a ytterbium doped fluoride glass sample.

Potential practical applications for anti-Stokes cooling of solids include radiation balanced solid state lasers and vibration-free optical refrigeration.

Other methods

Other methods of laser cooling include:

- Sisyphus cooling

- Resolved sideband cooling

- Raman sideband cooling

- Velocity selective coherent population trapping (VSCPT)

- Gray molasses

- Optical molasses

- Cavity-mediated cooling

- Use of a Zeeman slower

- Electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) cooling

- Anti-Stokes cooling in solids

- Polarization gradient cooling