A starving man lying on the ground in the Ukrainian SSR | |

| Native name | Советский голод 1930–1933 годов (Russian), Голодомор 1930–1933 років (Ukrainian), 1931–1933 жылдардағы кеңестік аштық (Kazakh) |

|---|---|

| Location | Russian SFSR (Kazakh ASSR), Ukrainian SSR |

| Type | Famine |

| Cause | Disputed; theories range from deliberate engineering to economic mismanagement, while others say low harvest due to demand spiking in industrialization in the Soviet Union |

| First reporter | Gareth Jones |

| Filmed by | Alexander Wienerberger |

| Deaths | ~5.7 to 8.7 million |

| Suspects | Joseph Stalin |

| Publication bans | Proof of the famine was suppressed by Goskomstat |

| Awards | Pulitzer Prize for Correspondence to Walter Duranty |

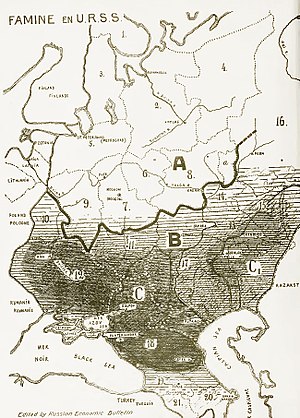

The Soviet famine of 1930–1933 was a famine in the major grain-producing areas of the Soviet Union, including Ukraine and different parts of Russia, including Northern Caucasus, Volga Region, Kazakhstan, the South Urals, and West Siberia. Estimates conclude that 5.7 to 8.7 million people died of famine across the Soviet Union. Major contributing factors to the famine include: the forced collectivization of agriculture as a part of the First Five-Year Plan, and forced grain procurement, combined with rapid industrialization and a decreasing agricultural workforce. Sources disagree on the possible role of drought. During this period the Soviet government escalated its persecution against the kulaks. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had ordered kulaks "to be liquidated as a class", so they became a target for the state. Persecution against the kulaks had been ongoing since the Russian Civil War, and had never fully subsided. Once collectivization became widely implemented, the persecution against the kulaks increased which culminated in a Soviet campaign of political repression, including arrests, deportations, and executions of large numbers of the kulaks in 1929–1932. Some kulaks responded by carrying out acts of sabotage such as killing livestock and destroying crops intended for consumption by factory workers. Despite the death toll mounting, Stalin chose to continue the Five Year Plan and collectivization. By 1934, the Soviet Union established an industrial baseline; however, it did come at the cost of millions of lives.

Some scholars have classified the famines which occurred in Ukraine and Kazakhstan as genocides which were committed by Stalin's government, targeting ethnic Ukrainians and Kazakhs. Others dispute the relevance of any ethnic motivation, as is frequently implied by that term, and focus on the class dynamics which existed between the land-owning peasants (kulaks) with strong political interests which were vested in the ownership of private property, and the ruling Soviet Communist party's fundamental tenets which were diametrically opposed to those interests. Gareth Jones was the first Western journalist to report the devastation.

Scholarly views

Genocide debates

The Holodomor genocide question remains a significant issue in modern politics and the debate as to whether or not Soviet policies would fall under the legal definition of genocide is disputed. Several scholars have disputed the allegation that the famine was a genocidal campaign which was waged by the Soviet government, including J. Arch Getty, Stephen G. Wheatcroft, R. W. Davies, and Mark Tauger. Getty says that the "overwhelming weight of opinion among scholars working in the new archives ... is that the terrible famine of the 1930s was the result of Stalinist bungling and rigidity rather than some genocidal plan." Wheatcroft says that the Soviet government's policies during the famine were criminal acts of fraud and manslaughter, though not outright murder or genocide. Joseph Stalin biographer Stephen Kotkin states that while "there is no question of Stalin's responsibility for the famine" and many deaths could have been prevented if not for the counterproductive and insufficient Soviet measures, there is no evidence for Stalin's intention to kill the Ukrainians deliberately. History professor Ronald Grigor Suny says that most scholars reject the view that the famine was an act of genocide, seeing it instead as resulting from badly conceived and miscalculated Soviet economic policies.

Professor of economics Michael Ellman critiqued Davies and Wheatcroft's view of intent as too narrow, stating: "According to them [Davies and Wheatcroft], only taking an action whose sole objective is to cause deaths among the peasantry counts as intent. Taking an action with some other goal (e.g. exporting grain to import machinery) but which the actor certainly knows will also cause peasants to starve does not count as intentionally starving the peasants. However, this is an interpretation of 'intent' which flies in the face of the general legal interpretation." Sociologist Martin Shaw supports this view, as he posits that if a leader knew the ultimate result of their policies would be mass death by famine, and they continue to enact them anyway, these deaths can be understood as intentional even if that was not the sole intent of the policies. Wheatcroft, in turn, criticizes this view in regard to the Soviet famine because he believes that the high expectations of central planners was sufficient to demonstrate their ignorance of the ultimate consequences of their actions and that the result of them would be famine. Ellman states that Stalin clearly committed crimes against humanity but whether he committed genocide depends on genocide definitions, and many other events would also have to be considered genocides. Additionally, Ellman is critical of the fixation on a "uniquely Stalinist evil" when it comes to excess deaths from famines, and argues that famines and droughts have been a common occurrence throughout Russian history, including the Russian famine of 1921–1922, which occurred before Stalin came to power. He also states that famines were widespread throughout the world in the 19th and 20th centuries in countries such as China, India, Ireland, and Russia. According to Ellman, the G8 "are guilty of mass manslaughter or mass deaths from criminal negligence because of their not taking obvious measures to reduce mass deaths", and Stalin's "behaviour was no worse than that of many rulers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Tauger gives more weight to natural disaster, in addition to crop failure, insufficient relief efforts, and to Soviet leaders' incompetence and paranoia in regards to foreign threats and peasant speculators, explaining the famine, and stated that "the harsh 1932–1933 procurements only displaced the famine from urban areas" but the low harvest "made a famine inevitable." Tauger stated that it is difficult to accept the famine "as the result of the 1932 grain procurements and as a conscious act of genocide" but that "the regime was still responsible for the deprivation and suffering of the Soviet population in the early 1930s", and "if anything, these data show that the effects of [collectivization and forced industrialization] were worse than has been assumed."

Some historians and scholars describe the famine as a genocide of the Kazakhs perpetrated by the Soviet state; however, there is scant evidence to support this view. Historian Sarah Cameron argues that while Stalin did not intend to starve Kazakhs, he saw some deaths as a necessary sacrifice to achieve the political and economic goals of the regime. Cameron believes that while the famine combined with a campaign against nomads was not genocide in the sense of the United Nations (UN) definition, it complies with Raphael Lemkin's original concept of genocide, which considered destruction of culture to be as genocidal as physical annihilation. Cameron also contends that the famine was a crime against humanity. Wheatcroft comments that in this vein peasant culture was also destroyed by the attempt to create a "New Soviet man" in his review of her book. Niccolò Pianciola, associate professor of history at Nazarbayev University, goes further and argues that from Lemkin's point of view on genocide all nomads of the Soviet Union were victims of the crime, not just the Kazakhs.

Causes

Unlike the Russian famine of 1921–1922, Russia's intermittent drought was not severe in the affected areas at this time. Despite this, historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft says that "there were two bad harvests in 1931 and 1932, largely but not wholly a result of natural conditions", within the Soviet Union. The most important natural factor in the Kazakh famine of 1930–1933 was the Zhut from 1927 to 1928, which was a period of extreme cold in which cattle were starved and were also unable to graze. Historian Mark Tauger of West Virginia University suggests that the famine was caused by a combination of factors, specifically low harvest due to natural disasters combined with increased demand for food caused by the urbanization and industrialization in the Soviet Union, and grain exports by the state at the same time. In regard to exports, Michael Ellman states that the 1932–1933 grain exports amounted to 1.8 million tonnes, which would have been enough to feed 5 million people for one year.According to archival research which was published by the United States Library of Congress in June 1992, the industrialization became a starting mechanism of the famine. Stalin's first five-year plan, adopted by the party in 1928, called for rapid industrialization of the economy. With the greatest share of investment put into heavy industry, widespread shortages of consumer goods occurred while the urban labour force was also increasing. Collectivization employed at the same time was expected to improve agricultural productivity and produce grain reserves sufficiently large to feed the growing urban labour force. The anticipated surplus was to pay for industrialization. Kulaks who were the wealthier peasants encountered particular hostility from the Stalin regime. About one million kulak households (1,803,392 people according to Soviet archival data) were liquidated by the Soviet Union. The kulaks had their property confiscated and were executed, imprisoned in the Gulag, or deported to penal labour camps in neighboring lands in a process called dekulakization. Forced collectivization of the remaining peasants was often fiercely resisted resulting in a disastrous disruption of agricultural productivity. Forced collectivization helped achieve Stalin's goal of rapid industrialization but it also contributed to a catastrophic famine in 1932–1933.

According to some scholars, collectivization in the Soviet Union and a lack of favored industries were the primary contributors to famine mortality (52% of excess deaths), and some evidence shows that ethnic Ukrainians and Germans were discriminated against. Lewis H. Siegelbaum, Professor of History at Michigan State University, states that Ukraine was hit particularly hard by grain quotas which were set at levels which most farms could not produce. The 1933 harvest was poor, coupled with the extremely high quota level, which led to starvation conditions. The shortages were blamed on kulak sabotage, and authorities distributed what supplies were available only in the urban areas. According to a Centre for Economic Policy Research paper published in 2021 by Andrei Markevich, Natalya Naumenko, and Nancy Qian, regions with higher Ukrainian population shares were struck harder with centrally planned policies corresponding to famine, and Ukrainian populated areas were given lower amounts of tractors which the paper argues demonstrates that ethnic discrimination across the board was centrally planned, ultimately concluding that 92% of famine deaths in Ukraine alone along with 77% of famine deaths in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus combined can be explained by systematic bias against Ukrainians. The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is somewhat called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses being Kyiv and Kharkiv, which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country. A potential explanation for this was that Kharkiv and Kyiv fulfilled and overfulfilled their grain procurements in 1930, which led to rations in these Oblasts having their procurement quotas doubled in 1931, compared to the national average increase in procurement rate of 9%, while Kharkiv and Kyiv had their quotas increased the Odesa oblast and some raions of Dnipropetrovsk oblast had their procurement quotas decreased. According to Nataliia Levchuk of the Ptoukha Institute of Demography and Social Studies, "the distribution of the largely increased 1931 grain quotas in Kharkiv and Kyiv oblasts by raion was very uneven and unjustified because it was done disproportionally to the percentage of wheat sown area and their potential grain capacity." Oleh Wolowyna comments that peasant resistance and the ensuing repression of said resistance was a critical factor for the famine in Ukraine and parts of Russia populated by national minorities like Germans and Ukrainians allegedly tainted by "fascism and bourgeois nationalism" according to Soviet authorities.

Historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft has given more weight to the "ill-conceived policies" of the Soviet government and in particular, he has highlighted the fact that while the policy did not specifically target Ukraine, Ukraine suffered the most for "demographic reasons"; Wheatcroft states that the main cause of starvation was a shortage of grain. According to Wheatcroft, the grain yield for the Soviet Union preceding the famine was a low harvest of between 55 and 60 million tons, likely in part caused by damp weather and low traction power, yet official statistics mistakenly (according to Wheatcroft and others) reported a yield of 68.9 million tons. In regard to the Soviet state's reaction to this crisis, Wheatcroft comments: "The good harvest of 1930 led to the decisions to export substantial amounts of grain in 1931 and 1932. The Soviet leaders also assumed that the wholesale socialisation of livestock farming would lead to the rapid growth of meat and dairy production. These policies failed, and the Soviet leaders attributed the failure not to their own lack of realism but to the machinations of enemies. Peasant resistance was blamed on the kulaks, and the increased use of force on a large scale almost completely replaced attempts at persuasion." Wheatcroft says that Soviet authorities refused to scale down grain procurements despite the low harvest, and that "[Wheatcroft and his colleague's] work has confirmed – if confirmation were needed – that the grain campaign in 1932/33 was unprecedentedly harsh and repressive." While Wheatcroft rejects the genocide characterization of the famine, he states that "the grain collection campaign was associated with the reversal of the previous policy of Ukrainisation."

Mark Tauger has estimated a harvest of 45 million tons, an estimate which is even lower than Wheatcroft's estimate, based on data which was collected from 40% of collective farms, an estimate which has been criticized by other scholars. Mark Tauger has suggested that drought and damp weather were causes of the low harvest. Mark Tauger suggested that heavy rains would help the harvest while Stephen Wheatcroft suggested it would hurt it which Natalya Naumenko notes as a disagreement in scholarship. Tauger has suggested that the harvest was reduced by other natural factors which included endemic plant rust and swarms of insects. However in regard to plant disease Stephen Wheatcroft notes that the Soviet extension of sown area may have exacerbated the problem. According to Tauger, warm and wet weather stimulated the growth of weeds, which was insufficiently dealt with due to primitive agricultural technology and a lack of motivation to work among the peasantry. Tauger has argued that when the peasants postponed their harvest work and left ears out on the field in order to glean them later as part of their resistance to collectivization, they produced an excessive crop yield which was eaten by an infestation of mice which destroyed grain stores and ate animal fodder, a situation which was worsened by the falling of deep snow.

Policies and events

Campaign against kulaks and bais

In February 1928, the Pravda newspaper published for the first time materials that claimed to expose the kulaks, and described widespread domination by the rich peasantry in the countryside and invasion by kulaks of communist party cells. Expropriation of grain stocks from kulaks and middle class peasants was called a "temporary emergency measure". Later, temporary emergency measures turned into a policy of "eliminating the kulaks as a class". The party's appeal to the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class had been formulated by Stalin, who stated: "In order to oust the kulaks as a class, the resistance of this class must be smashed in open battle and it must be deprived of the productive sources of its existence and development (free use of land, instruments of production, land-renting, right to hire labour, etc.). That is a turn towards the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class. Without it, talk about ousting the kulaks as a class is empty prattle, acceptable and profitable only to the Right deviators." Joseph Stalin announced the "liquidation of the kulaks as a class" on 27 December 1929.[61] Stalin had said: "Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes." In the ensuing campaign of repression against kulaks, more than 1.8 million peasants were deported in 1930–1931. The campaign had the stated purpose of fighting counter-revolution and of building socialism in the countryside. This policy, carried out simultaneously with collectivization in the Soviet Union, effectively brought all agriculture and all the labourers in Soviet Russia under state control.

Also in 1928 within Soviet Kazakhstan, authorities started a campaign to confiscate cattle from richer Kazakhs, who were called bai, known as Little October. The confiscation campaign was carried out by Kazakhs against other Kazakhs, and it was up to those Kazakhs to decide who was a bai and how much to confiscate from them. This engagement was intended to make Kazakhs active participants in the transformation of Kazakh society. More than 10,000 bais may have been deported due to the campaign against them.

Slaughter of livestock

During collectivization, the peasantry was required to relinquish their farm animals to government authorities. Many chose to slaughter their livestock rather than give them up to collective farms. In the first two months of 1930, kulaks killed millions of cattle, horses, pigs, sheep, and goats, with the meat and hides being consumed and bartered. In 1934, the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) reported that 26.6 million head of cattle and 63.4 million sheep had been lost. In response to the widespread slaughter, the Sovnarkom issued decrees to prosecute "the malicious slaughtering of livestock" (Russian: хищнический убой скота).

Agrotechnological failures

Historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft lists four problems Soviet authorities ignored that would hinder the advancement of agricultural technology and ultimately contributed to the famine:

- "Over-extension of the sown area" — Crops yields were reduced and likely some plant disease caused by the planting of future harvests across a wider area of land without rejuvenating soil leading to the reduction of fallow land.

- "Decline in draught power" — the over extraction of grain lead to the loss of food for farm animals, which in turn reduced the effectiveness of agricultural operations.

- "Quality of cultivation" — the planting and extracting of the harvest, along with ploughing was done in a poor manner due to inexperienced and demoralized workers and the aforementioned lack of draught power.

- "The poor weather" — drought and other poor weather conditions were largely ignored by Soviet authorities who gambled on good weather and believed agricultural difficulties would be overcome.

Food requisitioning

In the summer of 1930, the Soviet government had instituted a program of food requisitioning, ostensibly to increase grain exports. That same year, Ukraine produced 27% of the Soviet harvest but provided 38% of the deliveries, and made 42% of the deliveries in 1931; however, the Ukrainian harvest fell from 23.9 million tons to 18.3 million tons in 1931, and the previous year's quota of 7.7 million tons remained. Authorities were able to procure only 7.2 million tons, and just 4.3 million tons of a reduced quota of 6.6 million tons in 1932.

Between January and mid-April 1933, a factor contributing to a surge of deaths within certain regions of Ukraine during the period was the relentless search for alleged hidden grain by the confiscation of all food stuffs from certain households, which Stalin implicitly approved of through a telegram he sent on the 1 January 1933 to the Ukrainian government reminding Ukrainian farmers of the severe penalties for not surrendering grain they may be hiding. In his review of Anne Applebaum's book Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine, Mark Tauger gives a rough estimate of those affected by the search for hidden grain reserves: "In chapter 10 Applebaum describes the harsh searches that local personnel, often Ukrainian, imposed on villages, based on a Ukrainian memoir collection (222), and she presents many vivid anecdotes. Still she never explains how many people these actions affected. She cites a Ukrainian decree from November 1932 calling for 1100 brigades to be formed (229). If each of these 1100 brigades searched 100 households, and a peasant household had five people, then they took food from 550,000 people, out of 20 million, or about 2-3 percent." Meanwhile in Kazakhstan, livestock and grain were largely acquired between 1929 and 1932, with one-third of the republic's cereals being requisitioned and more than 1 million tons confiscated in 1930 to provide food for the cities. Historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft attributes the famine in Kazakhstan to the falsification of statistics produced by the local Soviet authorities to satisfy the unrealistic expectations of their superiors that lead to the over extraction of Kazakh resources.

Religious repression

Coiner of the term genocide, Raphael Lemkin considered the repression of the Orthodox Church to be a prong of genocide against Ukrainians when seen in correlation to the Holodomor famine. Collectivization did not just entail the acquisition of land from farmers but also the closing of churches, burning of icons, and the arrests of priests. Associating the church with the tsarist regime, the Soviet state continued to undermine the church through expropriations and repression. They cut off state financial support to the church and secularized church schools. Peasants began to associate Communists with atheists because the attack on the church was so devastating. Identification of Soviet power with the antichrist also decreased peasant support for the Soviet regime. Rumors about religious persecution spread mostly by word of mouth but also through leaflets and proclamations. Priests preached that the Antichrist had come to place "the Devil's mark" on the peasants.

Export of grain and other food

After recognition of the famine situation in Ukraine during the drought and poor harvests, the Soviet government in Moscow not only prevented some of the shipments of the export grain abroad, but also ordered the People's Commissariat of External Trade to purchase 57,332.4 tonns (3.5 million pounds) of grain in the Asian countries. Export of grain was also decreased in comparison with previous years. In 1930–1931, there had been 5,832,000 metric tons of grains exported. In 1931–1932, grain exports declined to 4,786,000 metric tons. In 1932–1933, grain exports were just 1,607,000 metric tons, and this further declined to 1,441,000 metric tons in 1933–1934.

Officially published data differed slightly:

- Cereals (in tonnes)

- 1930 – 4,846,024

- 1931 – 5,182,835

- 1932 – 1,819,114 (~750,000 during the first half of 1932; from late April ~157,000 tonnes of grain was also imported)

- 1933 – 1,771,364 (~220,000 during the first half of 1933; from late March grain was also imported)

- Only wheat (in tonnes)

- 1930 – 2,530,953

- 1931 – 2,498,958

- 1932 – 550,917

- 1933 – 748,248

In 1932, via Ukrainian commercial ports were exported 988,300 tons of grains and 16,500 tons of other types of cereals. In 1933, the totals were: 809,600 tons of grains, 2,600 tons of other cereals, 3,500 tons of meat, 400 tons of butter, and 2,500 tons of fish. Those same ports imported less than 67,200 tons of grains and cereals in 1932, and 8,600 tons of grains in 1933.

From other Soviet ports were received 164,000 tons of grains, 7,300 tons of other cereals, 31,500 tons of flour, and no more than 177,000 tons of meat and butter in 1932, and 230,000 tons of grains, 15,300 tons of other cereals, 100 tons of meat, 900 tons of butter, and 34,300 tons of fish in 1933.

Law of Spikelets

The "Decree About the Protection of Socialist Property", nicknamed by the farmers the Law of Spikelets, was enacted on 7 August 1932. The purpose of the law was to protect the property of the kolkhoz collective farms. It was nicknamed the Law of Spikelets because it allowed people to be prosecuted for gleaning leftover grain from the fields. However, in practice the law prohibited starving people from finding leftover food in the fields. There were more than 200,000 people sentenced under this law and the penalty for it was often death. According to researcher I.V. Pykhalov 3.5% of sentenced under the law of Spikelets were executed, 60.3% of sentenced received 10-year GULAG sentence while 36.2% were sentenced to less than 10 years. The general law courts sentenced 2686 to death between 7 August 1932 and 1 January 1933. Other types of law courts also issued death sentences under this law, e.g. Transportation Courts issued 812 death sentences under this law for the same period.

Blacklisting

The blacklist system was formalized in 1932 by the November 20 decree "The Struggle against Kurkul Influence in Collective Farms"; blacklisting, synonymous with a board of infamy, was one of the elements of agitation-propaganda in the Soviet Union, and especially Ukraine and the ethnically Ukrainian Kuban region in the 1930s, coinciding with the Holodomor, the artificial famine imposed by the Soviet regime as part of a policy of repression. Blacklisting was also used in Soviet Kazakhstan. A blacklisted collective farm, village, or raion (district) had its monetary loans and grain advances called in, stores closed, grain supplies, livestock, and food confiscated as a penalty, and was cut off from trade. Its Communist Party and collective farm committees were purged and subject to arrest, and their territory was forcibly cordoned off by the OGPU secret police.

Although nominally targeting collective farms failing to meet grain quotas and independent farmers with outstanding tax-in-kind, in practice the punishment was applied to all residents of affected villages and raions, including teachers, tradespeople, and children. In the end 37 out of 392 districts along with at least 400 collective farms where put on the "black board" in Ukraine, more than half of the blacklisted farms being in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast alone. Every single raion in Dnipropetrovsk had at least one blacklisted village, and in Vinnytsia oblast five entire raions were blacklisted. This oblast is situated right in the middle of traditional lands of the Zaporizhian Cossacks. Cossack villages were also blacklisted in the Volga and Kuban regions of Russia. In 1932, 32 (out of less than 200) districts in Kazakhstan that did not meet grain production quotas were blacklisted. Some blacklisted areas in Kharkiv could have death rates exceeding 40% while in other areas such as Vinnytsia blacklisting had no particular effect on mortality.

Passports

Joseph Stalin signed the January 1933 secret decree named "Preventing the Mass Exodus of Peasants who are Starving", restricting travel by peasants after requests for bread began in the Kuban and Ukraine; Soviet authorities blamed the exodus of peasants during the famine on anti-Soviet elements, saying that "like the outflow from Ukraine last year, was organized by the enemies of Soviet power." There was a wave of migration due to starvation and authorities responded by introducing a requirement that passports be used to go between republics and banning travel by rail.

The passport system in the Soviet Union (identity cards) was introduced on 27 December 1932 to deal with the exodus of peasants from the countryside. Individuals not having such a document could not leave their homes on pain of administrative penalties, such as internment in labour camps (Gulag). The rural population had no right to freely keep passports and thus could not leave their villages without approval. The power to issue passports rested with the head of the kolkhoz, and identity documents were kept by the administration of the collective farms. This measure stayed in place until 1974. Special barricades were set up by State Political Directorate units throughout the Soviet Union to prevent an exodus of peasants from hunger-stricken regions. During a single month in 1933, 219,460 people were either intercepted and escorted back or arrested and sentenced.

The lack of passports could not completely stop peasants leaving the countryside, but only a small percentage of those who illegally infiltrated into cities could improve their lot. Unable to find work or possibly buy or beg a little bread, farmers died in the streets of Kharkiv, Kyiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Poltava, Vinnytsia, and other major cities of Ukraine. It has been estimated that there were some 150,000 excess deaths as a result of this policy, and one historian asserts that these deaths constitute a crime against humanity. In contrast, historian Stephen Kotkin argues that the sealing of the Ukrainian borders caused by the internal passport system was in order to prevent the spread of famine related diseases.

Confiscation of reserve funds

In order to make up for unfulfilled grain procurement quotas in Ukraine, reserves of grain were confiscated from three sources including, according to Oleh Wolowyna, "(a) grain set aside for seed for the next harvest; (b) a grain fund for emergencies; (c) grain issued to collective farmers for previously completed work, which had to be returned if the collective farm did not fulfill its quota."

Purges

In Ukraine, there was a widespread purge of Communist party officials at all levels. According to Oleh Wolowyna, 390 "anti-Soviet, counter-revolutionary insurgent and chauvinist" groups were eliminated resulting in 37,797 arrests, that lead to 719 executions, 8,003 people being sent to Gulag camps, and 2,728 being put into internal exile. 120,000 individuals in Ukraine were reviewed in the first 10 months of 1933 in a top-to-bottom purge of the Communist party resulting in 23% being eliminated as perceived class hostile elements. Pavel Postyshev was set in charge of placing people at the head of Machine-Tractor Stations in Ukraine which were responsible for purging elements deemed to be class hostile. By the end of 1933, 60% of the heads of village councils and raion committees in Ukraine were replaced with an additional 40,000 lower-tier workers being purged.

Purges were also extensive in the Ukrainian populated territories of the Kuban and North Caucasus. 358 of 716 party secretaries in Kuban were removed, along with 43% of the 25,000 party members there; in total, 40% of the 115,000 to 120,000 rural party members in the North Caucasus were removed. Party officials associated with Ukrainization were targeted, as the national policy was viewed to be connected with the failure of grain procurement by Soviet authorities.

Refusal of foreign assistance

Despite the crisis, the Soviet government actively denied to ask for foreign aid for the famine and instead actively denied the famine's existence.

Cannibalism

Evidence of widespread cannibalism was documented during the famine within Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Some of the starving in Kazakhstan devolved into cannibalism ranging from eating leftover corpses to the famished actively murdering each other in order to feed. More than 2,500 people were convicted of cannibalism during the famine.

An example of a testimony of cannibalism in Ukraine during the famine is as follows: "Survival was a moral as well as a physical struggle. A woman doctor wrote to a friend in June 1933 that she had not yet become a cannibal, but was 'not sure that I shall not be one by the time my letter reaches you.' The good people died first. Those who refused to steal or to prostitute themselves died. Those who gave food to others died. Those who refused to eat corpses died. Those who refused to kill their fellow man died. Parents who resisted cannibalism died before their children did."

Famine refugees

"The old aul is now breaking apart, it is moving toward settled life, toward the use of hay fields, toward land cultivation; it is moving from worse land to better land, to state farms, to industry, to collective farm construction."

—Filipp Goloshchyokin, First Secretary of the Kazakh Regional Committee of the Communist Party

Due to starvation, between 665,000 and 1.1 million Kazakhs fled the famine with their cattle outside Kazakhstan to China, Mongolia, Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, and the Soviet republics of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Russia in search of food and employment in the new industrialization sites of Western Siberia. These refugees took an estimated 900,000 head of cattle with them.

Kazakhs who tried to escape were classified as class enemies and shot. The Soviet government also worked to repatriate them back to Soviet territory. This repatriation process could be brutal, as Kazakhs homes were broken into with both refugee and non-refugee Kazakhs being forcibly expelled onto train cars without food, heating, or water. 30% of the refugees died due to epidemics and hunger. Refugees that were repatriated were integrated into collective farms where many were too weak to work, and in a factory within Semipalatinsk half the refugees were fired within a few days with the other half being denied food rations.

Swiss reporter Ella Maillart, who traveled through Soviet Central Asia and China in the early 1930s, witnessed and wrote of viewing the firsthand effects of the repatriation campaign:As the refugees fled the famine, the Soviet government made violent attempts to stop them. In one case, relief dealers placed food in the back of a truck to attract refugees, and then locked the refugees inside the truck and dumped them in the middle of the mountains; the fate of these refugees is unknown. Thousands of Kazakhs were shot dead, and some were raped in their attempt to flee to China. The flight of refugees was framed by authorities as a progressive occurrence of nomads moving away from their 'primitive' lifestyle. Famine refugees were suspected by OGPU officials of maintaining counterrevolutionary, bai, and kulak 'tendencies', due to some refugees engaging in crime in the republics they arrived in. One report reads: “When one thinks of the extreme distress in which Kazakhs live here with us, one can easily imagine that things in Kazakhstan are much worse."“In every wagon carrying merchandise there were Kazakh families wearing rags. They killed time picking lice from each other. […] The train stops in the middle of a parched region. Packed alongside the railway are camels, cotton that is unloaded and weighed, piles of wheat in the open air. From the Kazakh wagons comes a muted hammering sound repeated the length of the train. Intrigued, I discover women pounding grain in mortars and making flour. The children ask to be lowered to the ground; they are wearing a quarter of a shirt on their shoulders and have scabs on their heads. A woman replaces her white turban, her only piece of clothing not in tatters, and I see her greasy hair and silver earrings. Her infant, clutching her dress and with skinny legs from which his boney knees protrude; his small behind is devoid of muscle, a small mass of rubbery, much-wrinkled skin. Where do they come from? Where are they going?”

Food aid

Historian Timothy D. Snyder says that the Moscow authorities refused to provide aid, despite the pleas for assistance and the acknowledged famine situation. Snyder stated that while Stalin had privately admitted that there was a famine in Ukraine, he did not grant a Ukrainian party leadership request for food aid. Some researchers state that aid was provided only during the summer. The first reports regarding malnutrition and hunger in rural areas and towns, which were undersupplied through the recently introduced rationing system, to the Ukrainian GPU and oblast authorities are dated to mid-January 1933; however, the first food aid sent by central Soviet authorities for the Odessa and Dnepropetrovsk regions 400 thousand poods (6,600 tonnes, 200 thousand poods, or 3,300 tonnes for each) appeared as early as 7 February 1933.

Measures were introduced to localize cases using locally available resources. While the numbers of such reports increased, the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine's central committee issued a decree on 8 February 1933, that urged every hunger case to be treated without delay and with a maximum mobilization of resources by kolkhozes, raions, towns, and oblasts. The decree set a seven-day term for food aid which was to be provided from central sources. On 20 February 1933, the Dnipropetrovsk oblast received 1.2 million poods of food aid, Odessa received 800 thousand, and Kharkiv received 300 thousand. The Kiev oblast was allocated 6 million poods by 18 March. The Ukrainian authorities also provided aid, but it was limited by available resources. In order to assist orphaned children, the Ukrainian GPU and People's Commissariat for Health created a special commission, which established a network of kindergartens where children could get food. Urban areas affected by food shortage adhered to a rationing system. On 20 March 1933, Stalin signed a decree which lowered the monthly milling levy in Ukraine by 14 thousand tons, which was to be redistributed as an additional bread supply "for students, small towns and small enterprises in large cities and specially in Kiev." However, food aid distribution was not managed effectively and was poorly redistributed by regional and local authorities.

After the first wave of hunger in February and March, Ukrainian authorities met with a second wave of hunger and starvation in April and May, specifically in the Kiev and Kharkiv oblasts. The situation was aggravated by the extended winter. Between February and June 1933, thirty-five Politburo decisions and Sovnarkom decrees authorized the issue of a total of 35.19 million poods (576,400 tonnes), or more than half of total aid to Soviet agriculture as a whole. 1.1 million tonnes were provided by central Soviet authorities in winter and spring 1933, among them grain and seeds for Ukrainian SSR peasants, kolhozes, and sovhozes. Such figures did not include grain and flour aid provided for the urban population and children, or aid from local sources. In Russia, Stalin personally authorized distribution of aid in answer to a request by Michail Aleksandrovich Sholokhov, whose own district was stricken. On 6 April 1933, Sholokhov, who lived in the Vesenskii district (Kuban, Russian SFSR), wrote at length to Stalin, describing the famine conditions and urging him to provide grain. Stalin received the letter on 15 April 1933, and the Politburo granted 700 tons of grain to that district on 6 April 1933. Stalin sent a telegram to Sholokhov stating: "We will do everything required. Inform size of necessary help. State a figure." Sholokhov replied on the same day, and on 22 April 1933, the day on which Stalin received the second letter, Stalin scolded him: "You should have sent your answer not by letter but by telegram. Time was wasted." Stalin also later reprimanded Sholokhov for failing to recognize perceived sabotage within his district; this was the only instance that a specific amount of aid was given to a specific district. Other appeals were not successful, and many desperate pleas were cut back or rejected.

Documents from Soviet archives indicate that the aid distribution was made selectively to the most affected areas, and during the spring months, such assistance was the goal of the relief effort. A special resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine for the Kiev Oblast from 31 March 1933 ordered peasants to be hospitalized with either ailing or recovering patients. The resolution ordered improved nutrition within the limits of available resources so that they could be sent out into the fields to sow the new crop as soon as possible. The food was dispensed according to special resolutions from government bodies, and additional food was given in the field where the labourers worked.

The last Politiburo's decision of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) about food aid to the whole of the Ukrainian SSR was issued on 13 June 1933. Separate orders about food aid for regions of Ukraine appeared by the end of June through early July 1933 for the Dnipropetrovsk, Vinnytsia, and Kiev regions. For the kolkhozes of the Kharkiv region, assistance was provided by end of July 1933 (Politburo decision dated 20 July 1933).

Selective distribution of aid

The distribution of food aid in the wake of the famine was selective in both Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Grain producing oblasts in Ukraine such as Dnipropetrovsk were given more aid at an earlier time than more severely affected regions like Kharkiv which produced less grain. Joseph Stalin had quoted Vladimir Lenin during the famine declaring: "He who does not work, neither shall he eat." This perspective is argued by Michael Ellman to have influenced official policy during the famine, with those deemed to be idlers being disfavored in aid distribution as compared to those deemed "conscientiously working collective farmers"; in this vein, Olga Andriewsky states that Soviet archives indicate that aid in Ukraine was primarily distributed to preserve the collective farm system and only the most productive workers were prioritized for receiving it. Food rationing in Ukraine was determined by city categories (where one lived, with capitals and industrial centers being given preferential distribution), occupational categories (with industrial and railroad workers being prioritized over blue collar workers and intelligentsia), status in the family unit (with employed persons being entitled to higher rations than dependents and the elderly), and type of workplace in relation to industrialization (with those who worked in industrial endeavors near steel mills being preferred in distribution over those who worked in rural areas or in food).

The discrimination in aid was arguably even worse in Kazakhstan, where Europeans had disproportionate power in the party which has been argued to be a cause of why indigenous nomads suffered the worst part of the collectivization process rather than the European sections of the country. During the famine, some ethnic Kazakhs were expelled from their land to make room for 200,000 forced settlers and Gulag prisoners, and some of the little Kazakh food went to such prisoners and settlers as well. Food aid to the Kazakhs was selectively distributed to eliminate class enemies such as the bais. Despite orders from above to the contrary, many Kazakhs were denied food aid as local officials considered them unproductive, and aid was provided to European workers in the country instead. Near the end of the Kazakh famine, Filipp Goloshchyokin was replaced with Levon Mirzoyan, who was repressive particularly toward famine refugees and denied food aid to areas run by cadres who asked for more food for their regions using "teary telegrams"; in one instance under Mirzoyan's rule, a plenipotentiary shoved food aid documents into his pocket and had a wedding celebration instead of transferring them for a whole month, while hundreds of Kazakhs starved.

Reactions

Some well-known journalists, most notably Walter Duranty of The New York Times, downplayed the famine and its death toll. In 1932, he received the Pulitzer Prize for Correspondence for his coverage of the Soviet Union's first five-year plan and was considered the most expert Western journalist to cover the famine. In the article "Russians Hungry, But Not Starving", he responded to an account of starvation in Ukraine and, while acknowledging that there was widespread malnutrition in certain areas of the Soviet Union, including parts of the North Caucasus and lower Volga Region, generally disagreed with the scale of the starvation and claimed that there was no famine. Duranty's coverage led directly to Franklin D. Roosevelt officially recognizing the Soviet Union in 1933 and revoked the United States' official recognition of an independent Ukraine. A similar position was taken by the French prime minister Edouard Herriot, who toured the territory of Ukraine during his stay in the Soviet Union. Other Western journalists reported on the famine at the time, including Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones, who both severely criticised Duranty's account and were later banned from returning to the Soviet Union.

As a child, Mikhail Gorbachev experienced the Soviet famine in Stavropol Krai, Russia. He recalled in a memoir that "In that terrible year [in 1933] nearly half the population of my native village, Privolnoye, starved to death, including two sisters and one brother of my father."

Members of the international community have denounced the Soviet government for the events of the years 1932–1933; however, the classification of the Ukrainian famine as a genocide is a subject of debate. A comprehensive criticism is presented by Michael Ellman in the article "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–1933 Revisited" published in the journal Europe-Asia Studies. Ellman refers to the Genocide Convention, which specifies that genocide is the destruction "in whole or in part" of a national group and "any acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group". The reasons for the famine are claimed to have been rooted in the industrialization and widespread collectivization of farms that involved escalating taxes, grain-delivery quotas, and dispossession of all property. The latter was met with resistance that was answered by "imposition of ever higher delivery quotas and confiscation of foodstuffs." As people were left with insufficient amount of food after the procurement, the famine occurred. Therefore, the famine occurred largely due to the policies that favored the goals of collectivization and industrialization rather than the deliberate attempt to destroy the Kazakhs or Ukrainians as a people.

In Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine, Pulitzer Prize winner Anne Applebaum says that the UN definition of genocide is overly narrow due to the Soviet influence on the Genocide Convention. Instead of a broad definition that would have included the Soviet crimes against kulaks and Ukrainians, Applebaum writes that genocide "came to mean the physical elimination of an entire ethnic group, in a manner similar to the Holocaust. The Holodomor does not meet that criterion ... This is hardly surprising, given that the Soviet Union itself helped shape the language precisely in order to prevent Soviet crimes, including the Holodomor, from being classified as 'genocide.'" Applebaum further states: "The accumulation of evidence means that it matters less, nowadays, whether the 1932–1933 famine is called a genocide, a crime against humanity, or simply an act of mass terror. Whatever the definition, it was a horrific assault, carried out by a government against its own people ... That the famine happened, that it was deliberate, and that it was part of a political plan to undermine Ukrainian identity is becoming more widely accepted, in Ukraine as well as in the West, whether or not an international court confirms it."

Estimation of the loss of life

It has been estimated that between 3.3 and 3.9 million died in Ukraine, between 2 and 3 million died in Russia, and 1.5–2 million (1.3 million of whom were ethnic Kazakhs) died in Kazakhstan. In addition to the Kazakh famine of 1919–1922, these events saw Kazakhstan lose more than half of its population within 15 years. The famine made Kazakhs a minority in their own republic. Before the famine, around 60% of the republic's population were Kazakhs; after the famine, only around 38% of the population were Kazakhs.

The exact number of deaths is hard to determine due to a lack of records, but the number increases significantly when the deaths in Ukrainian-majority Kuban region of Russia are included. Older estimates are still often cited in political commentary. In 1987, Robert Conquest had cited a number of Kazakhstan losses of one million; a large number of nomadic Kazakhs had roamed abroad, mostly to China and Mongolia. In 1993, "Population Dynamics: Consequences of Regular and Irregular Changes" reported that "general collectivization and repressions connected with it, as well as the 1933 famine, may be responsible for 7 million deaths." In 2007, David R. Marples estimated that 7.5 million people died as a result of the famine in Soviet Ukraine, of which 4 million were ethnic Ukrainians. According to the findings of the Court of Appeal of Kyiv in 2010, the demographic losses due to the famine amounted to 10 million, with 3.9 million direct famine deaths, and a further 6.1 million birth deficit. Later in 2010, Timothy Snyder estimated that around 3.3 million people died in total in Ukraine. In 2013, it was said that total excess deaths in Ukraine could not have exceeded 2.9 million.

Other estimates for famine dead are as follow:

- The 2004 book The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933 by R. W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft gives an estimate of 5.5 to 6.5 million deaths.

- The Encyclopædia Britannica estimates that 6 to 8 million people died from hunger in the Soviet Union during this period, of whom 4 to 5 million were Ukrainians. As of 2021, the Encyclopædia Britannica Online read: "Some 4 to 5 million died in Ukraine, and another 2 to 3 million in the North Caucasus and the Lower Volga area."

- Robert Conquest estimated at least 7 million peasants' deaths from hunger in the European part of the Soviet Union in 1932–33 (5 million in Ukraine, 1 million in the North Caucasus, and 1 million elsewhere), and an additional 1 million deaths from hunger as a result of collectivization in Kazakh ASSR.

- Another study by Michael Ellman using data given by Davies and Wheatcroft estimates "'about eight and a half million' victims of famine and repression" combined in the period 1930–1933.

- In his 2010 book Stalin's Genocides, Norman Naimark estimates that 3 to 5 million Ukrainians died in the famine.

- In 2008, the Russian State Duma issued a statement about the famine, stating that within territories of Povolzhe, Central Black Earth Region, Northern Caucasus, Ural, Crimea, Western Siberia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Belarus the estimated death toll is about 7 million people.

- The loss of life in the Ukrainian countryside is estimated at approximately 5 million people by another source.

- A 2020 Journal of Genocide Research article by Oleh Wolowyna estimated 8.7 million deaths across the entire Soviet Union including 3.9 million in Ukraine, 3.3 million in Russia, and 1.3 million in Kazakhstan, plus a lower number of dead in other republics.