Spontaneous parametric down-conversion process can split photons into type II photon pairs with mutually perpendicular polarization.

Quantum entanglement is a physical phenomenon which occurs when pairs or groups of particles are generated or interact in ways such that the quantum state of each particle cannot be described independently of the state of the other(s), even when the particles are separated by a large distance—instead, a quantum state must be described for the system as a whole.

Measurements of physical properties such as position, momentum, spin, and polarization, performed on entangled particles are found to be correlated. For example, if a pair of particles is generated in such a way that their total spin is known to be zero, and one particle is found to have clockwise spin on a certain axis, the spin of the other particle, measured on the same axis, will be found to be counterclockwise, as to be expected due to their entanglement. However, this behavior gives rise to paradoxical effects: any measurement of a property of a particle can be seen as acting on that particle (e.g., by collapsing a number of superposed states) and will change the original quantum property by some unknown amount; and in the case of entangled particles, such a measurement will be on the entangled system as a whole. It thus appears that one particle of an entangled pair "knows" what measurement has been performed on the other, and with what outcome, even though there is no known means for such information to be communicated between the particles, which at the time of measurement may be separated by arbitrarily large distances.

Such phenomena were the subject of a 1935 paper by Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen,[1] and several papers by Erwin Schrödinger shortly thereafter,[2][3] describing what came to be known as the EPR paradox. Einstein and others considered such behavior to be impossible, as it violated the local realist view of causality (Einstein referring to it as "spooky action at a distance")[4] and argued that the accepted formulation of quantum mechanics must therefore be incomplete. Later, however, the counterintuitive predictions of quantum mechanics were verified experimentally.[5]

Experiments have been performed involving measuring the polarization or spin of entangled particles in different directions, which—by producing violations of Bell's inequality—demonstrate statistically that the local realist view cannot be correct. This has been shown to occur even when the measurements are performed more quickly than light could travel between the sites of measurement: there is no lightspeed or slower influence that can pass between the entangled particles.[6]

Recent experiments have measured entangled particles within less than one hundredth of a percent of the travel time of light between them.[7] According to the formalism of quantum theory, the effect of measurement happens instantly.[8][9] It is not possible, however, to use this effect to transmit classical information at faster-than-light speeds[10] (see Faster-than-light § Quantum mechanics).

Quantum entanglement is an area of extremely active research by the physics community, and its effects have been demonstrated experimentally with photons,[11][12][13][14] neutrinos,[15] electrons,[16][17] molecules the size of buckyballs,[18][19] and even small diamonds.[20][21] Research is also focused on the utilization of entanglement effects in communication and computation.

History

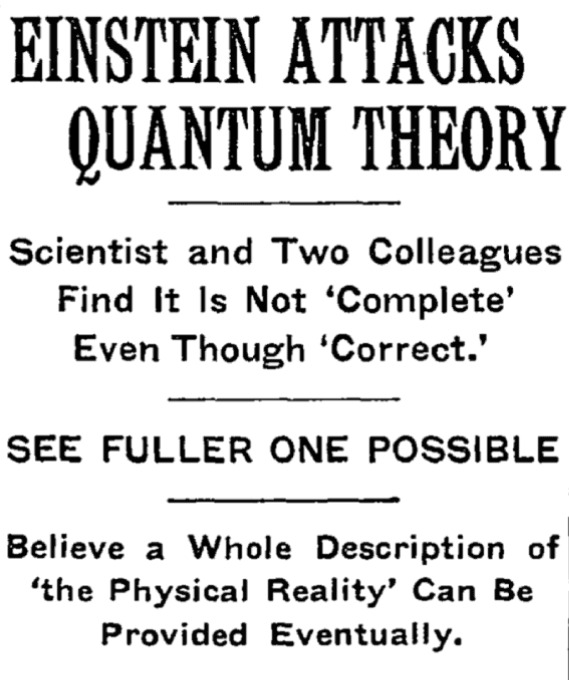

May 4, 1935 New York Times article headline regarding the imminent EPR paper.

The counterintuitive predictions of quantum mechanics about strongly correlated systems were first discussed by Albert Einstein in 1935, in a joint paper with Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen.[1] In this study, the three formulated the EPR paradox, a thought experiment that attempted to show that quantum mechanical theory was incomplete. They wrote: "We are thus forced to conclude that the quantum-mechanical description of physical reality given by wave functions is not complete."[1]

However, the three scientists did not coin the word entanglement, nor did they generalize the special properties of the state they considered. Following the EPR paper, Erwin Schrödinger wrote a letter to Einstein in German in which he used the word Verschränkung (translated by himself as entanglement) "to describe the correlations between two particles that interact and then separate, as in the EPR experiment."[22]

Schrödinger shortly thereafter published a seminal paper defining and discussing the notion of "entanglement." In the paper he recognized the importance of the concept, and stated:[2] "I would not call [entanglement] one but rather the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics, the one that enforces its entire departure from classical lines of thought."

Like Einstein, Schrödinger was dissatisfied with the concept of entanglement, because it seemed to violate the speed limit on the transmission of information implicit in the theory of relativity.[23] Einstein later famously derided entanglement as "spukhafte Fernwirkung"[24] or "spooky action at a distance."

The EPR paper generated significant interest among physicists and inspired much discussion about the foundations of quantum mechanics (perhaps most famously Bohm's interpretation of quantum mechanics), but produced relatively little other published work. So, despite the interest, the weak point in EPR's argument was not discovered until 1964, when John Stewart Bell proved that one of their key assumptions, the principle of locality, which underlies the kind of hidden variables interpretation hoped for by EPR, was mathematically inconsistent with the predictions of quantum theory.

Specifically, Bell demonstrated an upper limit, seen in Bell's inequality, regarding the strength of correlations that can be produced in any theory obeying local realism, and he showed that quantum theory predicts violations of this limit for certain entangled systems.[25] His inequality is experimentally testable, and there have been numerous relevant experiments, starting with the pioneering work of Stuart Freedman and John Clauser in 1972[26] and Alain Aspect's experiments in 1982,[27] all of which have shown agreement with quantum mechanics rather than the principle of local realism.

Until recently each had left open at least one loophole by which it was possible to question the validity of the results. However, in 2015 an experiment was performed that simultaneously closed both the detection and locality loopholes, and was heralded as "loophole-free"; this experiment ruled out a large class of local realism theories with certainty.[28] Alain Aspect notes that the setting-independence loophole, which he refers to as "far-fetched" yet a "residual loophole" that "cannot be ignored" has yet to be closed, and the free-will, or superdeterminism, loophole is unclosable, saying "no experiment, as ideal as it is, can be said to be totally loophole-free."[29]

A minority opinion holds that although quantum mechanics is correct, there is no superluminal instantaneous action-at-a-distance between entangled particles once the particles are separated.[30][31][32][33]

Bell's work raised the possibility of using these super-strong correlations as a resource for communication. It led to the discovery of quantum key distribution protocols, most famously BB84 by Charles H. Bennett and Gilles Brassard[34] and E91 by Artur Ekert.[35] Although BB84 does not use entanglement, Ekert's protocol uses the violation of a Bell's inequality as a proof of security.

Concept

Meaning of entanglement

An entangled system is defined to be one whose quantum state cannot be factored as a product of states of its local constituents; that is to say, they are not individual particles but are an inseparable whole. In entanglement, one constituent cannot be fully described without considering the other(s). Note that the state of a composite system is always expressible as a sum, or superposition, of products of states of local constituents; it is entangled if this sum necessarily has more than one term.Quantum systems can become entangled through various types of interactions. For some ways in which entanglement may be achieved for experimental purposes, see the section below on methods. Entanglement is broken when the entangled particles decohere through interaction with the environment; for example, when a measurement is made.[36]

As an example of entanglement: a subatomic particle decays into an entangled pair of other particles. The decay events obey the various conservation laws, and as a result, the measurement outcomes of one daughter particle must be highly correlated with the measurement outcomes of the other daughter particle (so that the total momenta, angular momenta, energy, and so forth remains roughly the same before and after this process). For instance, a spin-zero particle could decay into a pair of spin-½ particles. Since the total spin before and after this decay must be zero (conservation of angular momentum), whenever the first particle is measured to be spin up on some axis, the other, when measured on the same axis, is always found to be spin down. (This is called the spin anti-correlated case; and if the prior probabilities for measuring each spin are equal, the pair is said to be in the singlet state.)

The special property of entanglement can be better observed if we separate the said two particles. Let's put one of them in the White House in Washington and the other in Buckingham Palace (think about this as a thought experiment, not an actual one). Now, if we measure a particular characteristic of one of these particles (say, for example, spin), get a result, and then measure the other particle using the same criterion (spin along the same axis), we find that the result of the measurement of the second particle will match (in a complementary sense) the result of the measurement of the first particle, in that they will be opposite in their values.

The above result may or may not be perceived as surprising. A classical system would display the same property, and a hidden variable theory (see below) would certainly be required to do so, based on conservation of angular momentum in classical and quantum mechanics alike. The difference is that a classical system has definite values for all the observables all along, while the quantum system does not. In a sense to be discussed below, the quantum system considered here seems to acquire a probability distribution for the outcome of a measurement of the spin along any axis of the other particle upon measurement of the first particle. This probability distribution is in general different from what it would be without measurement of the first particle. This may certainly be perceived as surprising in the case of spatially separated entangled particles.

Paradox

The paradox is that a measurement made on either of the particles apparently collapses the state of the entire entangled system—and does so instantaneously, before any information about the measurement result could have been communicated to the other particle (assuming that information cannot travel faster than light) and hence assured the "proper" outcome of the measurement of the other part of the entangled pair. In the Copenhagen interpretation, the result of a spin measurement on one of the particles is a collapse into a state in which each particle has a definite spin (either up or down) along the axis of measurement. The outcome is taken to be random, with each possibility having a probability of 50%. However, if both spins are measured along the same axis, they are found to be anti-correlated. This means that the random outcome of the measurement made on one particle seems to have been transmitted to the other, so that it can make the "right choice" when it too is measured.[37]The distance and timing of the measurements can be chosen so as to make the interval between the two measurements spacelike, hence, any causal effect connecting the events would have to travel faster than light. According to the principles of special relativity, it is not possible for any information to travel between two such measuring events. It is not even possible to say which of the measurements came first. For two spacelike separated events x1 and x2 there are inertial frames in which x1 is first and others in which x2 is first. Therefore, the correlation between the two measurements cannot be explained as one measurement determining the other: different observers would disagree about the role of cause and effect.

Hidden variables theory

A possible resolution to the paradox is to assume that quantum theory is incomplete, and the result of measurements depends on predetermined "hidden variables".[38] The state of the particles being measured contains some hidden variables, whose values effectively determine, right from the moment of separation, what the outcomes of the spin measurements are going to be. This would mean that each particle carries all the required information with it, and nothing needs to be transmitted from one particle to the other at the time of measurement. Einstein and others (see the previous section) originally believed this was the only way out of the paradox, and the accepted quantum mechanical description (with a random measurement outcome) must be incomplete. (In fact similar paradoxes can arise even without entanglement: the position of a single particle is spread out over space, and two widely separated detectors attempting to detect the particle in two different places must instantaneously attain appropriate correlation, so that they do not both detect the particle.)Violations of Bell's inequality

The hidden variables theory fails, however, when we consider measurements of the spin of entangled particles along different axes (for example, along any of three axes that make angles of 120 degrees). If a large number of pairs of such measurements are made (on a large number of pairs of entangled particles), then statistically, if the local realist or hidden variables view were correct, the results would always satisfy Bell's inequality. A number of experiments have shown in practice that Bell's inequality is not satisfied. However, prior to 2015, all of these had loophole problems that were considered the most important by the community of physicists.[39][40] When measurements of the entangled particles are made in moving relativistic reference frames, in which each measurement (in its own relativistic time frame) occurs before the other, the measurement results remain correlated.[41][42]The fundamental issue about measuring spin along different axes is that these measurements cannot have definite values at the same time―they are incompatible in the sense that these measurements' maximum simultaneous precision is constrained by the uncertainty principle. This is contrary to what is found in classical physics, where any number of properties can be measured simultaneously with arbitrary accuracy. It has been proven mathematically that compatible measurements cannot show Bell-inequality-violating correlations,[43] and thus entanglement is a fundamentally non-classical phenomenon.

Other types of experiments

In experiments in 2012 and 2013, polarization correlation was created between photons that never coexisted in time.[44][45] The authors claimed that this result was achieved by entanglement swapping between two pairs of entangled photons after measuring the polarization of one photon of the early pair, and that it proves that quantum non-locality applies not only to space but also to time.In three independent experiments in 2013 it was shown that classically-communicated separable quantum states can be used to carry entangled states.[46] The first loophole-free Bell test was held in TU Delft in 2015 confirming the violation of Bell inequality.[47]

In August 2014, Brazilian researcher Gabriela Barreto Lemos and team were able to "take pictures" of objects using photons that had not interacted with the subjects, but were entangled with photons that did interact with such objects. Lemos, from the University of Vienna, is confident that this new quantum imaging technique could find application where low light imaging is imperative, in fields like biological or medical imaging.[48]

Mystery of time

There have been suggestions to look at the concept of time as an emergent phenomenon that is a side effect of quantum entanglement.[49][50] In other words, time is an entanglement phenomenon, which places all equal clock readings (of correctly prepared clocks, or of any objects usable as clocks) into the same history. This was first fully theorized by Don Page and William Wootters in 1983.[51] The Wheeler–DeWitt equation that combines general relativity and quantum mechanics – by leaving out time altogether – was introduced in the 1960s and it was taken up again in 1983, when the theorists Don Page and William Wootters made a solution based on the quantum phenomenon of entanglement. Page and Wootters argued that entanglement can be used to measure time.[52]In 2013, at the Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca Metrologica (INRIM) in Turin, Italy, researchers performed the first experimental test of Page and Wootters' ideas. Their result has been interpreted to confirm that time is an emergent phenomenon for internal observers but absent for external observers of the universe just as the Wheeler-DeWitt equation predicts.[52]

Source for the arrow of time

Physicist Seth Lloyd says that quantum uncertainty gives rise to entanglement, the putative source of the arrow of time. According to Lloyd; "The arrow of time is an arrow of increasing correlations."[53] The approach to entanglement would be from the perspective of the causal arrow of time, with the assumption that the cause of the measurement of one particle determines the effect of the result of the other particle's measurement.Non-locality and entanglement

In the media and popular science, quantum non-locality is often portrayed as being equivalent to entanglement. While it is true that a pure bipartite quantum state must be entangled in order for it to produce non-local correlations, there exist entangled states that do not produce such correlations, and there exist non-entangled (separable) quantum states that present some non-local behaviour. A well-known example of the first case is the Werner state that is entangled for certain values of , but can always be described using local hidden variables.[54]

In short, entanglement of a two-party state is necessary but not

sufficient for that state to be non-local. Moreover, it was shown that,

for arbitrary number of party, there exist states that are genuinely

entangled but admits a fully local strategy. It is important to

recognize that entanglement is more commonly viewed as an algebraic

concept, noted for being a precedent to non-locality as well as to quantum teleportation and to superdense coding, whereas non-locality is defined according to experimental statistics and is much more involved with the foundations and interpretations of quantum mechanics.

, but can always be described using local hidden variables.[54]

In short, entanglement of a two-party state is necessary but not

sufficient for that state to be non-local. Moreover, it was shown that,

for arbitrary number of party, there exist states that are genuinely

entangled but admits a fully local strategy. It is important to

recognize that entanglement is more commonly viewed as an algebraic

concept, noted for being a precedent to non-locality as well as to quantum teleportation and to superdense coding, whereas non-locality is defined according to experimental statistics and is much more involved with the foundations and interpretations of quantum mechanics.Quantum mechanical framework

The following subsections are for those with a good working knowledge of the formal, mathematical description of quantum mechanics, including familiarity with the formalism and theoretical framework developed in the articles: bra–ket notation and mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics.Pure states

Consider two noninteracting systems A and B, with respective Hilbert spaces HA and HB. The Hilbert space of the composite system is the tensor product and the second in state

and the second in state  , the state of the composite system is

, the state of the composite system isNot all states are separable states (and thus product states). Fix a basis

for HA and a basis

for HA and a basis  for HB. The most general state in HA ⊗ HB is of the form

for HB. The most general state in HA ⊗ HB is of the form.

![{\displaystyle \scriptstyle [c_{i}^{A}],[c_{j}^{B}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e589a6b1f44cb3d763716fd930b19f7184291fd0) so that

so that  yielding

yielding  and

and  It is inseparable if for any vectors

It is inseparable if for any vectors ![\scriptstyle [c^A_i],[c^B_j]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e589a6b1f44cb3d763716fd930b19f7184291fd0) at least for one pair of coordinates

at least for one pair of coordinates  we have

we have  If a state is inseparable, it is called an entangled state.

If a state is inseparable, it is called an entangled state.For example, given two basis vectors

of HA and two basis vectors

of HA and two basis vectors  of HB, the following is an entangled state:

of HB, the following is an entangled state:Now suppose Alice is an observer for system A, and Bob is an observer for system B. If in the entangled state given above Alice makes a measurement in the

eigenbasis of A, there are two possible outcomes, occurring with equal probability:[56]

eigenbasis of A, there are two possible outcomes, occurring with equal probability:[56]- Alice measures 0, and the state of the system collapses to

.

- Alice measures 1, and the state of the system collapses to

.

The outcome of Alice's measurement is random. Alice cannot decide which state to collapse the composite system into, and therefore cannot transmit information to Bob by acting on her system. Causality is thus preserved, in this particular scheme. For the general argument, see no-communication theorem.

Ensembles

As mentioned above, a state of a quantum system is given by a unit vector in a Hilbert space. More generally, if one has less information about the system, then one calls it an ensemble and describes it by a density matrix, which is a positive-semidefinite matrix, or a trace class when the state space is infinite-dimensional, and has trace 1. Again, by the spectral theorem, such a matrix takes the general form: . When a mixed state has rank 1, it therefore describes a pure ensemble. When there is less than total information about the state of a quantum system we need density matrices to represent the state.

. When a mixed state has rank 1, it therefore describes a pure ensemble. When there is less than total information about the state of a quantum system we need density matrices to represent the state.Experimentally, a mixed ensemble might be realized as follows. Consider a "black box" apparatus that spits electrons towards an observer. The electrons' Hilbert spaces are identical. The apparatus might produce electrons that are all in the same state; in this case, the electrons received by the observer are then a pure ensemble. However, the apparatus could produce electrons in different states. For example, it could produce two populations of electrons: one with state

with spins aligned in the positive z direction, and the other with state

with spins aligned in the positive z direction, and the other with state  with spins aligned in the negative y

direction. Generally, this is a mixed ensemble, as there can be any

number of populations, each corresponding to a different state.

with spins aligned in the negative y

direction. Generally, this is a mixed ensemble, as there can be any

number of populations, each corresponding to a different state.Following the definition above, for a bipartite composite system, mixed states are just density matrices on HA ⊗ HB. That is, it has the general form

, and the vectors are unit vectors. This is self-adjoint and positive and has trace 1.

, and the vectors are unit vectors. This is self-adjoint and positive and has trace 1.Extending the definition of separability from the pure case, we say that a mixed state is separable if it can be written as[57]:131–132

's and

's and  's are themselves mixed states (density operators) on the subsystems A and B

respectively. In other words, a state is separable if it is a

probability distribution over uncorrelated states, or product states. By

writing the density matrices as sums of pure ensembles and expanding,

we may assume without loss of generality that

's are themselves mixed states (density operators) on the subsystems A and B

respectively. In other words, a state is separable if it is a

probability distribution over uncorrelated states, or product states. By

writing the density matrices as sums of pure ensembles and expanding,

we may assume without loss of generality that  and

and  are themselves pure ensembles. A state is then said to be entangled if it is not separable.

are themselves pure ensembles. A state is then said to be entangled if it is not separable.In general, finding out whether or not a mixed state is entangled is considered difficult. The general bipartite case has been shown to be NP-hard.[58] For the 2 × 2 and 2 × 3 cases, a necessary and sufficient criterion for separability is given by the famous Positive Partial Transpose (PPT) condition.[59]

Reduced density matrices

The idea of a reduced density matrix was introduced by Paul Dirac in 1930.[60] Consider as above systems A and B each with a Hilbert space HA, HB. Let the state of the composite system be.

For example, the reduced density matrix of A for the entangled state

discussed above is

discussed above is.

Two applications that use them

Reduced density matrices were explicitly calculated in different spin chains with unique ground state. An example is the one-dimensional AKLT spin chain:[61] the ground state can be divided into a block and an environment. The reduced density matrix of the block is proportional to a projector to a degenerate ground state of another Hamiltonian.The reduced density matrix also was evaluated for XY spin chains, where it has full rank. It was proved that in the thermodynamic limit, the spectrum of the reduced density matrix of a large block of spins is an exact geometric sequence[62] in this case.

Entropy

In this section, the entropy of a mixed state is discussed as well as how it can be viewed as a measure of quantum entanglement.Definition

The plot of von Neumann entropy Vs Eigenvalue for a bipartite 2-level

pure state. When the eigenvalue has value .5, von Neumann entropy is at a

maximum, corresponding to maximum entanglement.

In classical information theory H, the Shannon entropy, is associated to a probability distribution,

, in the following way:[63]

, in the following way:[63] , log2(ρ) turns out to be nothing more than the operator with the same eigenvectors, but the eigenvalues

, log2(ρ) turns out to be nothing more than the operator with the same eigenvectors, but the eigenvalues  . The Shannon entropy is then:

. The Shannon entropy is then:.

As a measure of entanglement

Entropy provides one tool that can be used to quantify entanglement, although other entanglement measures exist.[64] If the overall system is pure, the entropy of one subsystem can be used to measure its degree of entanglement with the other subsystems.For bipartite pure states, the von Neumann entropy of reduced states is the unique measure of entanglement in the sense that it is the only function on the family of states that satisfies certain axioms required of an entanglement measure.

It is a classical result that the Shannon entropy achieves its maximum at, and only at, the uniform probability distribution {1/n,...,1/n}. Therefore, a bipartite pure state ρ ∈ HA ⊗ HB is said to be a maximally entangled state if the reduced state[clarification needed] of ρ is the diagonal matrix

As an aside, the information-theoretic definition is closely related to entropy in the sense of statistical mechanics[citation needed] (comparing the two definitions, we note that, in the present context, it is customary to set the Boltzmann constant k = 1). For example, by properties of the Borel functional calculus, we see that for any unitary operator U,

In particular, U could be the time evolution operator of the system, i.e.,

The reversibility of a process is associated with the resulting entropy change, i.e., a process is reversible if, and only if, it leaves the entropy of the system invariant. Therefore, the march of the arrow of time towards thermodynamic equilibrium is simply the growing spread of quantum entanglement.[65] This provides a connection between quantum information theory and thermodynamics.

Rényi entropy also can be used as a measure of entanglement.

Entanglement measures

Entanglement measures quantify the amount of entanglement in a (often viewed as a bipartite) quantum state. As aforementioned, entanglement entropy is the standard measure of entanglement for pure states (but no longer a measure of entanglement for mixed states). For mixed states, there are some entanglement measures in the literature[64] and no single one is standard.- Entanglement cost

- Distillable entanglement

- Entanglement of formation

- Relative entropy of entanglement

- Squashed entanglement

- Logarithmic negativity

Quantum field theory

The Reeh-Schlieder theorem of quantum field theory is sometimes seen as an analogue of quantum entanglement.Applications

Entanglement has many applications in quantum information theory. With the aid of entanglement, otherwise impossible tasks may be achieved.Among the best-known applications of entanglement are superdense coding and quantum teleportation.[67]

Most researchers believe that entanglement is necessary to realize quantum computing (although this is disputed by some).[68]

Entanglement is used in some protocols of quantum cryptography.[69][70] This is because the "shared noise" of entanglement makes for an excellent one-time pad. Moreover, since measurement of either member of an entangled pair destroys the entanglement they share, entanglement-based quantum cryptography allows the sender and receiver to more easily detect the presence of an interceptor.[citation needed]

In interferometry, entanglement is necessary for surpassing the standard quantum limit and achieving the Heisenberg limit.[71]

Entangled states

There are several canonical entangled states that appear often in theory and experiments.For two qubits, the Bell states are

.

For M>2 qubits, the GHZ state is

for

for  . The traditional GHZ state was defined for

. The traditional GHZ state was defined for  . GHZ states are occasionally extended to qudits, i.e., systems of d rather than 2 dimensions.

. GHZ states are occasionally extended to qudits, i.e., systems of d rather than 2 dimensions.Also for M>2 qubits, there are spin squeezed states.[72] Spin squeezed states are a class of squeezed coherent states satisfying certain restrictions on the uncertainty of spin measurements, and are necessarily entangled.[73] Spin squeezed states are good candidates for enhancing precision measurements using quantum entanglement.[74]

For two bosonic modes, a NOON state is

except the basis kets 0 and 1 have been replaced with "the N photons are in one mode" and "the N photons are in the other mode".

except the basis kets 0 and 1 have been replaced with "the N photons are in one mode" and "the N photons are in the other mode".Finally, there also exist twin Fock states for bosonic modes, which can be created by feeding a Fock state into two arms leading to a beam splitter. They are the sum of multiple of NOON states, and can used to achieve the Heisenberg limit.[75]

For the appropriately chosen measure of entanglement, Bell, GHZ, and NOON states are maximally entangled while spin squeezed and twin Fock states are only partially entangled. The partially entangled states are generally easier to prepare experimentally.

Methods of creating entanglement

Entanglement is usually created by direct interactions between subatomic particles. These interactions can take numerous forms. One of the most commonly used methods is spontaneous parametric down-conversion to generate a pair of photons entangled in polarisation.[76] Other methods include the use of a fiber coupler to confine and mix photons, photons emitted from decay cascade of the bi-exciton in a quantum dot [77], the use of the Hong-Ou-Mandel effect, etc., In the earliest tests of Bell's theorem, the entangled particles were generated using atomic cascades.It is also possible to create entanglement between quantum systems that never directly interacted, through the use of entanglement swapping.

Testing a system for entanglement

Systems which contain no entanglement are said to be separable. For 2-Qubit and Qubit-Qutrit systems (2 × 2 and 2 × 3 respectively) the simple Peres–Horodecki criterion provides both a necessary and a sufficient criterion for separability, and thus for detecting entanglement. However, for the general case, the criterion is merely a sufficient one for separability, as the problem becomes NP-hard.[78][79] A numerical approach to the problem is suggested by Jon Magne Leinaas, Jan Myrheim and Eirik Ovrum in their paper "Geometrical aspects of entanglement".[80] Leinaas et al. offer a numerical approach, iteratively refining an estimated separable state towards the target state to be tested, and checking if the target state can indeed be reached. An implementation of the algorithm (including a built-in Peres-Horodecki criterion testing) is brought in the "StateSeparator" web-app.In 2016 China launched the world’s first quantum communications satellite.[81] The $100m Quantum Experiments at Space Scale (QUESS) mission was launched on Aug 16, 2016, from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northern China at 01:40 local time.

For the next two years, the craft – nicknamed "Micius" after the ancient Chinese philosopher – will demonstrate the feasibility of quantum communication between Earth and space, and test quantum entanglement over unprecedented distances.

In the June 16, 2017, issue of Science, Yin et al. report setting a new quantum entanglement distance record of 1203 km, demonstrating the survival of a 2-photon pair and a violation of a Bell inequality, reaching a CHSH valuation of 2.37 ± 0.09, under strict Einstein locality conditions, from the Micius satellite to bases in Lijian, Yunnan and Delingha, Quinhai, increasing the efficiency of transmission over prior fiberoptic experiments by an order of magnitude.[82]

![\rho =\sum _{{i}}w_{i}\left[\sum _{{j}}{\bar {c}}_{{ij}}(|\alpha _{{ij}}\rangle \otimes |\beta _{{ij}}\rangle )\right]\otimes \left[\sum _{k}c_{{ik}}(\langle \alpha _{{ik}}|\otimes \langle \beta _{{ik}}|)\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bf6f2bd84a64fac8cafbb0c06e14180aad4e4401)