| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Ethyl(2-mercaptobenzoato-(2-)-O,S) mercurate(1-) sodium

| |

| Other names

Mercury((o-carboxyphenyl)thio)ethyl sodium salt

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.192 |

| EC Number | 200-210-4 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number | OV8400000 |

| UNII | |

| Properties | |

| C9H9HgNaO2S | |

| Molar mass | 404.81 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or slightly yellow powder |

| Density | 2.508 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 232 to 233 °C (450 to 451 °F; 505 to 506 K) (decomposition) |

| 1000 g/l (20 °C) | |

| Pharmacology | |

| D08AK06 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS signal word | Danger |

| H300, H310, H330, H373, H410 | |

| P260, P273, P280, P301, P310, P330, P302, P352, P310, P304, P340, P310 | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 250 °C (482 °F; 523 K) |

Thiomersal (INN), or thimerosal (USAN, JAN), is an organomercury compound. This compound is a well-established antiseptic and antifungal agent.

The pharmaceutical corporation Eli Lilly and Company gave thiomersal the trade name Merthiolate. It has been used as a preservative in vaccines, immunoglobulin preparations, skin test antigens, antivenins, ophthalmic and nasal products, and tattoo inks. Its use as a vaccine preservative was controversial, and it was phased out from routine childhood vaccines in the European Union, and a few other countries in response to popular fears. As of 2019, scientific consensus is that these fears are unsubstantiated.

History

Morris Kharasch, a chemist then at the University of Maryland filed a patent application for thiomersal in 1927; Eli Lilly later marketed the compound under the trade name Merthiolate. In vitro tests conducted by Lilly investigators H. M. Powell and W. A. Jamieson found that it was forty to fifty times as effective as phenol against Staphylococcus aureus.

It was used to kill bacteria and prevent contamination in antiseptic

ointments, creams, jellies, and sprays used by consumers and in

hospitals, including nasal sprays, eye drops, contact lens solutions, immunoglobulins, and vaccines. Thiomersal was used as a preservative (bactericide)

so that multidose vials of vaccines could be used instead of

single-dose vials, which are more expensive. By 1938, Lilly's assistant

director of research listed thiomersal as one of the five most important

drugs ever developed by the company.

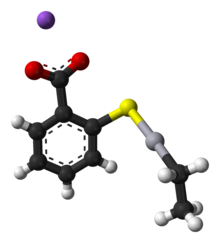

Structure

Thiomersal features mercury(II) with a coordination number 2, i.e. two ligands are attached to Hg, the thiolate and the ethyl group. The carboxylate

group confers solubility in water. Like other two-coordinate Hg(II)

compounds, the coordination geometry of Hg is linear, with a 180° S-Hg-C

angle. Typically, organomercury thiolate compounds are prepared from

organomercury chlorides.

Uses

Thiomersal's main use is as an antiseptic and antifungal agent, due to the oligodynamic effect. In multidose injectable drug delivery systems, it prevents serious adverse effects such as the Staphylococcus infection that, in one 1928 incident, killed 12 of 21 children vaccinated with a diphtheria vaccine that lacked a preservative. Unlike other vaccine preservatives used at the time, thiomersal does not reduce the potency of the vaccines that it protects. Bacteriostatics such as thiomersal are not needed in single-dose injectables.

In the United States, countries in the European Union and a few

other affluent countries, thiomersal is no longer used as a preservative

in routine childhood vaccination schedules.

In the U.S., the only exceptions among vaccines routinely recommended

for children are some formulations of the inactivated influenza vaccine

for children older than two years. Several vaccines that are not routinely recommended for young children do contain thiomersal, including DT (diphtheria and tetanus),

Td (tetanus and diphtheria), and TT (tetanus toxoid); other vaccines

may contain a trace of thiomersal from steps in manufacture. The multi-dose versions of the influenza vaccines Fluvirin and Fluzone can contain up to 25 micrograms of mercury per dose from thiomersal. Also, four rarely used treatments for pit viper, coral snake, and black widow venom still contain thiomersal. Outside North America and Europe, many vaccines contain thiomersal; the World Health Organization

has concluded that there is no evidence of toxicity from thiomersal in

vaccines and no reason on safety grounds to change to more expensive

single-dose administration. The United Nations Environment Program

backed away from an earlier proposal of adding thiomersal in vaccines

to the list of banned compounds in a treaty aimed at reducing exposure

to mercury worldwide.

Citing medical and scientific consensus that thiomersal in vaccines

posed no safety issues, but that eliminating the preservative in

multi-dose vaccines, primarily used in developing countries, will lead

to high cost and a requirement for refrigeration which the developing

countries can ill afford, the UN's final decision is to exclude

thiomersal from the treaty.

Toxicology

Thiomersal is very toxic by inhalation, ingestion, and in contact with skin (EC hazard symbol

T+), with a danger of cumulative effects. It is also very toxic to

aquatic organisms and may cause long-term adverse effects in aquatic

environments (EC hazard symbol N). In the body, it is metabolized or degraded to ethylmercury (C2H5Hg+) and thiosalicylate.

Cases have been reported of severe mercury poisoning by accidental exposure or attempted suicide, with some fatalities.

Animal experiments suggest that thiomersal rapidly dissociates to

release ethylmercury after injection; that the disposition patterns of

mercury are similar to those after exposure to equivalent doses of

ethylmercury chloride; and that the central nervous system and the

kidneys are targets, with lack of motor coordination being a common

sign. Similar signs and symptoms have been observed in accidental human poisonings.

The mechanisms of toxic action are unknown. Fecal excretion accounts

for most of the elimination from the body. Ethylmercury clears from

blood with a half-life of about 18 days in adults by breakdown into other chemicals, including inorganic mercury.

Ethylmercury is eliminated from the brain in about 14 days in infant

monkeys. Risk assessment for effects on the nervous system have been

made by extrapolating from dose-response relationships for methylmercury. Methylmercury and ethylmercury distribute to all body tissues, crossing the blood–brain barrier and the placental barrier, and ethylmercury also moves freely throughout the body.

Concerns based on extrapolations from methylmercury caused thiomersal

to be removed from U.S. childhood vaccines, starting in 1999. Since

then, it has been found that ethylmercury is eliminated from the body

and the brain significantly faster than methylmercury, so the late-1990s

risk assessments turned out to be overly conservative.

Though inorganic mercury metabolized from ethylmercury has a much

longer half-life in the brain, at least 120 days, it appears to be much

less toxic than the inorganic mercury produced from mercury vapor, for reasons not yet understood.

Allergies

Thiomersal is used in patch testing

for people who have dermatitis, conjunctivitis, and other potentially

allergic reactions. A 2007 study in Norway found that 1.9% of adults had

a positive patch test reaction to thiomersal; a higher prevalence of contact allergy (up to 6.6%) was observed in German populations. Thiomersal-sensitive individuals can receive intramuscular rather than subcutaneous immunization,

though there have been no large sample sized studies regarding this

matter to date. In real-world practice on vaccination of adult

populations, contact allergy does not seem to elicit clinical reaction. Thiomersal allergy has decreased in Denmark, probably because of its exclusion from vaccines there.

In a recent study of Polish children and adolescents with

chronic/recurrent eczema, positive reactions to thiomersal were found in

11.7% of children (7–8 y.o.) and 37.6% of adolescents (16–17 y.o.).

This difference in the sensitization rates can be explained by changing

exposure patterns: The adolescents have received six

thiomersal-preserved vaccines during their life course, with the last

immunization taking place 2–3 years before the mentioned study, younger

children received only four thiomersal-preserved vaccines, with the last

one applied 5 years before the study, while further immunizations were

performed with new thiomersal-free vaccines.

Autism

Following a review of mercury-containing food and drugs mandated in 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics

asked vaccine manufacturers to remove thiomersal from vaccines as a

purely precautionary measure, and it was rapidly phased out of most U.S.

and European vaccines.

Many parents saw the action to remove thiomersal—in the setting of a

perceived increasing rate of autism as well as increasing number of

vaccines in the childhood vaccination schedule—as indicating that the

preservative was the cause of autism. The scientific consensus

is that there is no evidence supporting these claims, and the rate of

autism continues to climb despite elimination of thiomersal from routine

childhood vaccines. Major scientific and medical bodies such as the Institute of Medicine and World Health Organization, as well as governmental agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration and the CDC reject any role for thiomersal in autism or other neurodevelopmental disorders.

This controversy has caused harm due to parents attempting to treat

their autistic children with unproven and possibly dangerous treatments,

discouraging parents from vaccinating their children due to fears about

thiomersal toxicity, and diverting resources away from research into more promising areas for the cause of autism. Thousands of lawsuits have been filed in a U.S. federal court to seek damages from alleged toxicity from vaccines, including those purportedly caused by thiomersal.