| |

| Abbreviation | NAACP |

|---|---|

| Formation | February 12, 1909 |

| Purpose | "To ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to eliminate racial hatred and racial discrimination." |

| Headquarters | Baltimore, Maryland, US |

Membership

| 500,000 |

Chairman

| Leon W. Russell |

President and CEO

| Derrick Johnson |

Main organ

| Board of directors |

Budget

| $24,828,336 |

| Website | naacp.org |

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as a bi-racial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington and Moorfield Storey.

Its mission in the 21st century is "to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to eliminate race-based discrimination." National NAACP initiatives include political lobbying, publicity efforts and litigation strategies developed by its legal team. The group enlarged its mission in the late 20th century by considering issues such as police misconduct, the status of black foreign refugees and questions of economic development. Its name, retained in accordance with tradition, uses the once common term colored people, referring to those with some African ancestry.

The NAACP bestows annual awards to African Americans in two categories: Image Awards are for achievement in the arts and entertainment, and Spingarn Medals are for outstanding achievement of any kind. Its headquarters is in Baltimore, Maryland.

Organization

The NAACP is headquartered in Baltimore, with additional regional offices in New York, Michigan, Georgia, Maryland, Texas, Colorado and California. Each regional office is responsible for coordinating the efforts of state conferences in that region. Local, youth, and college chapters organize activities for individual members.In the U.S., the NAACP is administered by a 64-member board, led by a chairperson. The board elects one person as the president and one as chief executive officer for the organization. Julian Bond, Civil Rights Movement activist and former Georgia State Senator, was chairman until replaced in February 2010 by health-care administrator Roslyn Brock. For decades in the first half of the 20th century, the organization was effectively led by its executive secretary, who acted as chief operating officer. James Weldon Johnson and Walter F. White, who served in that role successively from 1920 to 1958, were much more widely known as NAACP leaders than were presidents during those years.

The organization has never had a woman president, except on a temporary basis, and there have been calls to name one. Lorraine C. Miller served as interim president after Benjamin Jealous stepped down. Maya Wiley was rumored to be in line for the position in 2013, but Cornell William Brooks was selected.

Departments within the NAACP govern areas of action. Local chapters are supported by the 'Branch and Field Services' department and the 'Youth and College' department. The 'Legal' department focuses on court cases of broad application to minorities, such as systematic discrimination in employment, government, or education. The Washington, D.C., bureau is responsible for lobbying the U.S. government, and the Education Department works to improve public education at the local, state and federal levels. The goal of the Health Division is to advance health care for minorities through public policy initiatives and education.

As of 2007, the NAACP had approximately 425,000 paying and non-paying members.

The NAACP's non-current records are housed at the Library of Congress, which has served as the organization's official repository since 1964. The records held there comprise approximately five million items spanning the NAACP's history from the time of its founding until 2003. In 2011, the NAACP teamed with the digital repository ProQuest to digitize and host online the earlier portion of its archives, through 1972 – nearly two million pages of documents, from the national, legal, and branch offices throughout the country, which offer first-hand insight into the organization's work related to such crucial issues as lynching, school desegregation, and discrimination in all its aspects (in the military, the criminal justice system, employment, housing).

Predecessor: The Niagara Movement

The Pan-American Exposition of 1901 in Buffalo, New York featured many American innovations and achievements, but also included a disparaging caricature of slave life in the South as well as a depiction of life in Africa, called "Old Plantation" and "Darkest Africa," respectively. A local African-American woman, Mary Talbert of Ohio, was appalled by the exhibit, as a similar one in Paris highlighted black achievements. She informed W. E. B. DuBois of the situation, and a coalition began to form.In 1905, a group of thirty-two prominent African-American leaders met to discuss the challenges facing African Americans and possible strategies and solutions. They were particularly concerned by the Southern states' disenfranchisement of blacks starting with Mississippi's passage of a new constitution in 1890. Through 1908, southern legislatures dominated by white Democrats ratified new constitutions and laws creating barriers to voter registration and more complex election rules. In practice, this caused the exclusion of most blacks and many poor whites from the political system in southern states, crippling the Republican Party in most of the South. Black voter registration and turnout dropped markedly in the South as a result of such legislation. Men who had been voting for thirty years in the South were told they did not "qualify" to register. White-dominated legislatures also passed segregation and Jim Crow laws.

Because hotels in the US were segregated, the men convened in Canada at the Erie Beach Hotel on the Canadian side of the Niagara River in Fort Erie, Ontario. As a result, the group came to be known as the Niagara Movement. A year later, three non-African-Americans joined the group: journalist William English Walling, a wealthy socialist; and social workers Mary White Ovington and Henry Moskowitz. Moskowitz, who was Jewish, was then also Associate Leader of the New York Society for Ethical Culture. They met in 1906 at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and in 1907 in Boston, Massachusetts.

The fledgling group struggled for a time with limited resources and internal conflict, and disbanded in 1910. Seven of the members of the Niagara Movement joined the Board of Directors of the NAACP, founded in 1909. Although both organizations shared membership and overlapped for a time, the Niagara Movement was a separate organization. Historically, it is considered to have had a more radical platform than the NAACP. The Niagara Movement was formed exclusively by African Americans. Three European Americans were among the founders of the NAACP.

History

Formation

Founders of the NAACP: Moorfield Storey, Mary White Ovington and W.E.B. Du Bois.

The Race Riot of 1908 in Springfield, Illinois, the state capital and President Abraham Lincoln's

hometown, was a catalyst showing the urgent need for an effective civil

rights organization in the U.S. In the decades around the turn of the

century, the rate of lynchings of blacks, particularly men, was at an all-time high. Mary White Ovington, journalist William English Walling and Henry Moskowitz met in New York City in January 1909 to work on organizing for black civil rights.

They sent out solicitations for support to more than 60 prominent

Americans, and set a meeting date for February 12, 1909. This was

intended to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the birth of

President Abraham Lincoln, who emancipated enslaved African Americans.

While the first large meeting did not take place until three months

later, the February date is often cited as the founding date of the

organization.

The NAACP was founded on February 12, 1909, by a larger group including African Americans W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, Archibald Grimké, Mary Church Terrell, and the previously named whites Henry Moskowitz, Mary White Ovington, William English Walling (the wealthy Socialist son of a former slave-holding family), Florence Kelley, a social reformer and friend of Du Bois; Oswald Garrison Villard, and Charles Edward Russell, a renowned muckraker and close friend of Walling. Russell helped plan the NAACP and had served as acting chairman of the National Negro Committee (1909), a forerunner to the NAACP.

On May 30, 1909, the Niagara Movement conference took place at New York City's Henry Street Settlement House; they created an organization of more than 40, identifying as the National Negro Committee. Among other founding members was Lillian Wald, a nurse who had founded the Henry Street Settlement where the conference took place.

Du Bois played a key role in organizing the event and presided over the proceedings. Also in attendance was Ida B. Wells-Barnett, an African-American journalist and anti-lynching crusader. At their second conference on May 30, 1910, members chose the new organization's name to be the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and elected its first officers:

- National President, Moorfield Storey, Boston

- Chairman of the Executive Committee, William English Walling

- Treasurer, John E. Milholland (a Lincoln Republican and Presbyterian from New York City and Lewis, New York)

- Disbursing Treasurer, Oswald Garrison Villard

- Executive Secretary, Frances Blascoer

- Director of Publicity and Research, W. E. B. Du Bois.

The NAACP was incorporated a year later in 1911. The association's charter expressed its mission:

To promote equality of rights and to eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the courts, education for the children, employment according to their ability and complete equality before law.

The larger conference resulted in a more diverse organization, where the leadership was predominantly white. Moorfield Storey,

a white attorney from a Boston abolitionist family, served as the

president of the NAACP from its founding to 1915. At its founding, the

NAACP had one African American on its executive board, Du Bois. Storey

was a long-time classical liberal and Grover Cleveland Democrat who advocated laissez-faire free markets, the gold standard, and anti-imperialism. Storey consistently and aggressively championed civil rights, not only for blacks but also for Native Americans

and immigrants (he opposed immigration restrictions). Du Bois continued

to play a pivotal leadership role in the organization, serving as

editor of the association's magazine, The Crisis, which had a circulation of more than 30,000.

The Crisis was used both for news reporting and for

publishing African-American poetry and literature. During the

organization's campaigns against lynching, Du Bois encouraged the

writing and performance of plays and other expressive literature about

this issue.

The Jewish community contributed greatly to the NAACP's founding and continued financing. Jewish historian Howard Sachar writes in his book A History of Jews in America that "In 1914, Professor Emeritus Joel Spingarn of Columbia University became chairman of the NAACP and recruited for its board such Jewish leaders as Jacob Schiff, Jacob Billikopf, and Rabbi Stephen Wise."

Jim Crow and disenfranchisement

An African American drinks out of a segregated water cooler designated for "colored" patrons in 1939 at a streetcar terminal in Oklahoma City.

Sign for the "colored" waiting room at a bus station in Durham, North Carolina, 1940

In its early years, the NAACP was based in New York City. It

concentrated on litigation in efforts to overturn disenfranchisement of

blacks, which had been established in every southern state by 1908,

excluding most from the political system, and the Jim Crow statutes that legalized racial segregation.

In 1913, the NAACP organized opposition to President Woodrow Wilson's

introduction of racial segregation into federal government policy,

workplaces, and hiring. African-American women's clubs were among the

organizations that protested Wilson's changes, but the administration

did not alter its assuagement of Southern cabinet members and the

Southern block in Congress.

By 1914, the group had 6,000 members and 50 branches. It was

influential in winning the right of African Americans to serve as

military officers in World War I.

Six hundred African-American officers were commissioned and 700,000 men

registered for the draft. The following year, the NAACP organized a

nationwide protest, with marches in numerous cities, against D. W. Griffith's silent movie The Birth of a Nation, a film that glamorized the Ku Klux Klan. As a result, several cities refused to allow the film to open.

The NAACP began to lead lawsuits targeting disfranchisement and

racial segregation early in its history. It played a significant part in

the challenge of Guinn v. United States (1915) to Oklahoma's discriminatory grandfather clause,

which effectively disenfranchised most black citizens while exempting

many whites from certain voter registration requirements. It persuaded

the Supreme Court of the United States to rule in Buchanan v. Warley

in 1917 that state and local governments cannot officially segregate

African Americans into separate residential districts. The Court's

opinion reflected the jurisprudence of property rights and freedom of

contract as embodied in the earlier precedent it established in Lochner v. New York.

In 1916, chairman Joel Spingarn invited James Weldon Johnson to serve as field secretary. Johnson was a former U.S. consul to Venezuela

and a noted African-American scholar and columnist. Within four years,

Johnson was instrumental in increasing the NAACP's membership from 9,000

to almost 90,000. In 1920, Johnson was elected head of the

organization. Over the next ten years, the NAACP escalated its lobbying

and litigation efforts, becoming internationally known for its advocacy

of equal rights and equal protection for the "American Negro."

The NAACP devoted much of its energy during the interwar years to fighting the lynching

of blacks throughout the United States by working for legislation,

lobbying and educating the public. The organization sent its field

secretary Walter F. White to Phillips County, Arkansas, in October 1919, to investigate the Elaine Race Riot.

More than 200 black tenant farmers were killed by roving white

vigilantes and federal troops after a deputy sheriff's attack on a union

meeting of sharecroppers left one white man dead. White published his report on the riot in the Chicago Daily News.

The NAACP organized the appeals for twelve black men sentenced to death

a month later based on the fact that testimony used in their

convictions was obtained by beatings and electric shocks. It gained a

groundbreaking Supreme Court decision in Moore v. Dempsey 261 U.S. 86

(1923) that significantly expanded the Federal courts' oversight of the

states' criminal justice systems in the years to come. White

investigated eight race riots and 41 lynchings for the NAACP and

directed its study Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States.

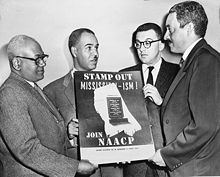

NAACP leaders Henry L. Moon, Roy Wilkins, Herbert Hill, and Thurgood Marshall in 1956.

The NAACP also worked for more than a decade seeking federal anti-lynching legislation, but the Solid South

of white Democrats voted as a bloc against it or used the filibuster in

the Senate to block passage. Because of disenfranchisement, African

Americans in the South were unable to elect representatives of their

choice to office. The NAACP regularly displayed a black flag stating "A

Man Was Lynched Yesterday" from the window of its offices in New York to

mark each lynching.

In alliance with the American Federation of Labor, the NAACP led the successful fight to prevent the nomination of John Johnston Parker

to the Supreme Court, based on his support for denying the vote to

blacks and his anti-labor rulings. It organized legal support for the Scottsboro Boys. The NAACP lost most of the internecine battles with the Communist Party and International Labor Defense over the control of those cases and the legal strategy to be pursued in that case.

The organization also brought litigation to challenge the "white primary"

system in the South. Southern state Democratic parties had created

white-only primaries as another way of barring blacks from the political

process. Since southern states were dominated by the Democrats, the

primaries were the only competitive contests. In 1944 in Smith v. Allwright,

the Supreme Court ruled against the white primary. Although states had

to retract legislation related to the white primaries, the legislatures

soon came up with new methods to severely limit the franchise for

blacks.

Legal Defense Fund

The board of directors of the NAACP created the Legal Defense Fund

in 1939 specifically for tax purposes. It functioned as the NAACP legal

department. Intimidated by the Department of the Treasury and the

Internal Revenue Service, the Legal and Educational Defense Fund, Inc.,

became a separate legal entity in 1957, although it was clear that it

was to operate in accordance with NAACP policy. After 1961 serious

disputes emerged between the two organizations, creating considerable

confusion in the eyes and minds of the public.

Desegregation

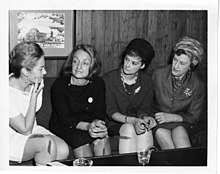

NAACP representatives E. Franklin Jackson and Stephen Gill Spottswood meeting with President Kennedy at the White House in 1961

By the 1940s the federal courts were amenable to lawsuits regarding

constitutional rights, which Congressional action was virtually

impossible. With the rise of private corporate litigators such as the

NAACP to bear the expense, civil suits became the pattern in modern

civil rights litigation. The NAACP's Legal department, headed by Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall, undertook a campaign spanning several decades to bring about the reversal of the "separate but equal" doctrine announced by the Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson.

The NAACP's Baltimore chapter, under president Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson, challenged segregation in Maryland state professional schools by supporting the 1935 Murray v. Pearson case argued by Marshall. Houston's victory in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938) led to the formation of the Legal Defense Fund in 1939.

Locals viewing the bomb-damaged home of Arthur Shores, NAACP attorney, Birmingham, Alabama, on September 5, 1963. The bomb exploded on September 4, the previous day, injuring Shores' wife.

The campaign for desegregation culminated in a unanimous 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that held state-sponsored segregation of public elementary schools was unconstitutional. Bolstered by that victory, the NAACP pushed for full desegregation throughout the South.[30] NAACP activists were excited about the judicial strategy. Starting on December 5, 1955, NAACP activists, including Edgar Nixon, its local president, and Rosa Parks, who had served as the chapter's Secretary, helped organize a bus boycott in Montgomery,

Alabama. This was designed to protest segregation on the city's buses,

two-thirds of whose riders were black. The boycott lasted 381 days.

The State of Alabama responded by effectively barring the NAACP from

operating within its borders because of its refusal to divulge a list of

its members. The NAACP feared members could be fired or face violent

retaliation for their activities. Although the Supreme Court eventually

overturned the state's action in NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958), the NAACP lost its leadership role in the Civil Rights Movement while it was barred from Alabama.

New organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

(SNCC) rose up with different approaches to activism. These newer

groups relied on direct action and mass mobilization to advance the

rights of African Americans, rather than litigation and legislation. Roy Wilkins, NAACP's executive director, clashed repeatedly with Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders over questions of strategy and leadership within the movement.

The NAACP continued to use the Supreme Court's decision in Brown

to press for desegregation of schools and public facilities throughout

the country. Daisy Bates, president of its Arkansas state chapter, spearheaded the campaign by the Little Rock Nine to integrate the public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas.

By the mid-1960s, the NAACP had regained some of its preeminence in the Civil Rights Movement by pressing for civil rights legislation. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

took place on August 28, 1963. That fall President John F. Kennedy sent

a civil rights bill to Congress before he was assassinated.

President Lyndon B. Johnson

worked hard to persuade Congress to pass a civil rights bill aimed at

ending racial discrimination in employment, education and public

accommodations, and succeeded in gaining passage in July 1964. He

followed that with passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

which provided for protection of the franchise, with a role for federal

oversight and administrators in places where voter turnout was

historically low.

The FBI's COINTELPRO program targeted civil rights groups, including the NAACP, for infiltration, disruption and discreditation.

After Kivie Kaplan died in 1975, scientist W. Montague Cobb became President of the NAACP and served until 1982. Benjamin Hooks, a lawyer and clergyman, was elected as the NAACP's executive director in 1977, after the retirement of Roy Wilkins.

The 1990s

In the 1990s, the NAACP ran into debt. The dismissal of two leading

officials further added to the picture of an organization in deep

crisis.

In 1993 the NAACP's Board of Directors narrowly selected Reverend Benjamin Chavis over Reverend Jesse Jackson

to fill the position of Executive Director. A controversial figure,

Chavis was ousted eighteen months later by the same board. They accused

him of using NAACP funds for an out-of-court settlement in a sexual

harassment lawsuit.

Following the dismissal of Chavis, Myrlie Evers-Williams narrowly defeated NAACP chairperson William Gibson for president in 1995, after Gibson was accused of overspending and mismanagement of the organization's funds.

In 1996 Congressman Kweisi Mfume, a Democratic Congressman from Maryland and former head of the Congressional Black Caucus,

was named the organization's president. Three years later strained

finances forced the organization to drastically cut its staff, from 250

in 1992 to 50.

In the second half of the 1990s, the organization restored its

finances, permitting the NAACP National Voter Fund to launch a major

get-out-the-vote offensive in the 2000 U.S. presidential elections. 10.5 million African Americans cast their ballots in the election. This was one million more than four years before. The NAACP's effort was credited by observers as playing a significant role in Democrat Al Gore's winning several states where the election was close, such as Pennsylvania and Michigan.

Lee Alcorn controversy

During the 2000 Presidential election, Lee Alcorn, president of the Dallas NAACP branch, criticized Al Gore's selection of Senator Joe Lieberman

for his Vice-Presidential candidate because Lieberman was Jewish. On a

gospel talk radio show on station KHVN, Alcorn stated, "If we get a Jew

person, then what I'm wondering is, I mean, what is this movement for,

you know? Does it have anything to do with the failed peace

talks?"..."So I think we need to be very suspicious of any kind of

partnerships between the Jews at that kind of level because we know that

their interest primarily has to do with money and these kind of

things."

NAACP President Kweisi Mfume

immediately suspended Alcorn and condemned his remarks. Mfume stated,

"I strongly condemn those remarks. I find them to be repulsive,

anti-Semitic, anti-NAACP and anti-American. Mr. Alcorn does not speak

for the NAACP, its board, its staff or its membership. We are proud of

our long-standing relationship with the Jewish community and I personally will not tolerate statements that run counter to the history and beliefs of the NAACP in that regard."

Alcorn, who had been suspended three times in the previous five

years for misconduct, subsequently resigned from the NAACP. He founded

what he called the Coalition for the Advancement of Civil Rights. Alcorn

criticized the NAACP, saying, "I can't support the leadership of the

NAACP. Large amounts of money are being given to them by large

corporations that I have a problem with."

Alcorn also said, "I cannot be bought. For this reason I gladly offer

my resignation and my membership to the NAACP because I cannot work

under these constraints."

Alcorn's remarks were also condemned by the Reverend Jesse Jackson,

Jewish groups and George W. Bush's rival Republican presidential

campaign. Jackson said he strongly supported Lieberman's addition to the

Democratic ticket, saying, "When we live our faith, we live under the law. He [Lieberman] is a firewall of exemplary behavior."

Al Sharpton, another prominent African-American leader, said, "The appointment of Mr. Lieberman was to be welcomed as a positive step." The leaders of the American Jewish Congress

praised the NAACP for its quick response, stating that: "It will take

more than one bigot like Alcorn to shake the sense of fellowship of American Jews

with the NAACP and black America ... Our common concerns are too

urgent, our history too long, our connection too sturdy, to let anything

like this disturb our relationship."

George W. Bush

Louisiana NAACP leads Jena March 6.

In 2004, President George W. Bush declined an invitation to speak to the NAACP's national convention.

Bush's spokesperson said that Bush had declined the invitation to speak

to the NAACP because of harsh statements about him by its leaders.

In an interview, Bush said, "I would describe my relationship with the

current leadership as basically nonexistent. You've heard the rhetoric

and the names they've called me." Bush said he admired some members of the NAACP and would seek to work with them "in other ways."

On July 20, 2006, Bush addressed the NAACP national convention.

He made a bid for increasing support by African Americans for

Republicans, in the midst of a midterm election. He referred to

Republican Party support for civil rights.

Tax exempt status

In October 2004 the Internal Revenue Service informed the NAACP that it was investigating its tax-exempt status based on chairman Julian Bond's speech at its 2004 Convention, in which he criticized President George W. Bush as well as other political figures. In general, the US Internal Revenue Code prohibits organizations granted tax-exempt

status from "directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening

in, any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any

candidate for elective public office."

The NAACP denounced the investigation as retaliation for its success in

increasing the number of African Americans who were voting.

In August 2006, the IRS investigation concluded with the agency's

finding "that the remarks did not violate the group's tax-exempt

status."

LGBT rights

As the American LGBT rights movement gained steam after the Stonewall riots

of 1969, the NAACP became increasingly affected by the movement to gain

rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. Bond, while

chairman of the NAACP, became an outspoken supporter of the rights of

gays and lesbians, and stated his support for same-sex marriage. He boycotted the 2004 funeral services for Coretta Scott King,

as he said the King children had chosen an anti-gay megachurch. This

was in contradiction to their mother's longstanding support for the

rights of gay and lesbian people. In a 2005 speech in Richmond, Virginia, Bond said:

- African Americans ... were the only Americans who were enslaved for two centuries, but we were far from the only Americans suffering discrimination then and now. ... Sexual disposition parallels race. I was born this way. I have no choice. I wouldn't change it if I could. Sexuality is unchangeable.

In a 2007 speech on the Martin Luther King Day Celebration at Clayton State University in Morrow,

Georgia, Bond said, "If you don't like gay marriage, don't get gay

married." His positions have pitted elements of the NAACP against

religious groups in the Civil Rights Movement who oppose gay marriage,

mostly within the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCLC). The NAACP became increasingly vocal in opposition against

state-level constitutional amendments to ban same-sex marriage and

related rights. State NAACP leaders such as William J. Barber, II of North Carolina participated actively against North Carolina Amendment 1 in 2012, but it was passed by conservative voters.

On May 19, 2012, the NAACP's board of directors formally endorsed

same-sex marriage as a civil right, voting 62–2 for the policy in a Miami, Florida quarterly meeting.

Benjamin Jealous, the organization's president, said of the decision,

"Civil marriage is a civil right and a matter of civil law. ... The

NAACP's support for marriage equality is deeply rooted in the 14th Amendment

of the United States Constitution and equal protection of all people."

Possibly significant in the NAACP's vote was its concern with the HIV/AIDS crisis

in the black community; while AIDS support organizations recommend that

people live a monogamous lifestyle, the government did not recognize

same-sex relationships as part of this.

As a result of this endorsement, Rev. Keith Ratliff Sr. of Des Moines, Iowa resigned from the NAACP board.

Travel warning regarding Missouri

On June 7, 2017, the NAACP issued a warning for African-American travelers to Missouri:

Individuals traveling in the state are advised to travel with extreme CAUTION. Race, gender and color based crimes have a long history in Missouri. Missouri, home of Lloyd Gaines, Dred Scott and the dubious distinction of the Missouri Compromise and one of the last states to lose its slaveholding past, may not be safe. ... [Missouri Senate Bill] SB 43 legalizes individual discrimination and harassment in Missouri and would prevent individuals from protecting themselves from discrimination, harassment, and retaliation in Missouri.

Moreover, over-zealous enforcement of routine traffic violations in Missouri against African Americans has resulted in an increasing trend that shows African Americans are 75% more likely to be stopped than Caucasians.

Missouri NAACP Conference president Rod Chapel, Jr., suggested that visitors to Missouri "should have bail money."

Geography

The organization's national initiatives, political lobbying, and

publicity efforts were handled by the headquarters staff in New York and

Washington DC. Court strategies were developed by the legal team based

for many years at Howard University.

NAACP local branches have also been important. When, in its early years, the national office launched campaigns against The Birth of a Nation,

it was the local branches that carried out the boycotts. When the

organization fought to expose and outlaw lynching, the branches carried

the campaign into hundreds of communities. And while the Legal Defense

Fund developed a federal court strategy of legal challenges to

segregation, many branches fought discrimination using state laws and

local political opportunities, sometimes winning important victories.

Those victories were mostly achieved in Northern and Western states before World War II.

When the Southern civil rights movement gained momentum in the 1940s

and 1950s, credit went both to the Legal Defense Fund attorneys and to

the massive network of local branches that Ella Baker and other organizers had spread across the region.

Local organizations built a culture of Black political activism.

Current activities

NAACP President & CEO Benjamin Jealous and former president Bill Clinton during the Medgar Evers wreath-laying ceremony in Arlington, June 5, 2013

Youth

Youth sections of the NAACP were established in 1936; there are now

more than 600 groups with a total of more than 30,000 individuals in

this category. The NAACP Youth & College Division is a branch of the

NAACP in which youth are actively involved. The Youth Council is

composed of hundreds of state, county, high school and college

operations where youth (and college students) volunteer to share their

opinions with their peers and address issues that are local and

national. Sometimes volunteer work expands to a more international

scale.

Youth and College Division

"The mission of the NAACP Youth & College Division shall be to

inform youth of the problems affecting African Americans and other

racial and ethnic minorities; to advance the economic, education, social

and political status of African Americans and other racial and ethnic

minorities and their harmonious cooperation with other peoples; to

stimulate an appreciation of the African Diaspora and other African

Americans' contribution to civilization; and to develop an intelligent,

militant effective youth leadership."

ACT-SO program

Since 1978 the NAACP has sponsored the Afro-Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics

(ACT-SO) program for high school youth around the United States. The

program is designed to recognize and award African-American youth who

demonstrate accomplishment in academics, technology, and the arts. Local

chapters sponsor competitions in various categories for young people in

grades 9–12. Winners of the local competitions are eligible to proceed

to the national event at a convention held each summer at locations

around the United States. Winners at the national competition receive

national recognition, along with cash awards and various prizes.

Awards

- NAACP Image Awards – honoring African-American achievements in film, television, music,

- NAACP Theatre Awards – honoring African-American achievements in theatre productions

- Spingarn Medal – honoring general African-American achievements

- Thalheimer Award – for achievements by NAACP branches and chapters

- Montague Cobb Award – honoring African-American achievement in the field of health

- Nathaniel Jones Award for Public Service – first awarded to public servants in 2018

- Foot Soldier In the Sands Award – awarded to attorneys who have contributed legal expertise to the NAACP on a pro bono basis

- Juanita Jackson Mitchell Award for Legal Activism – awarded to a NAACP unit for "exemplary legal redress committee activities"

- William Robert Ming Advocacy Award – awarded to lawyers who exemplify personal and financial sacrifice for human equality

Partner organizations

The Emerald Cities Collaborative is a partner organization with the NAACP.