| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈklɔːrəkwiːn/ |

| Trade names | Aralen, other |

| Other names | Chloroquine phosphate |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1-2 months |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.175 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

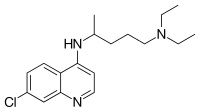

| Formula | C18H26ClN3 |

| Molar mass | 319.872 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| (verify) | |

Chloroquine is a medication primarily used to prevent and treat malaria in areas where malaria remains sensitive to its effects. Certain types of malaria, resistant strains, and complicated cases typically require different or additional medication. Chloroquine is also occasionally used for amebiasis that is occurring outside the intestines, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus erythematosus. While it has not been formally studied in pregnancy, it appears safe. It is also being studied to treat COVID-19 as of 2020. It is taken by mouth.

Common side effects include muscle problems, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and skin rash. Serious side effects include problems with vision, muscle damage, seizures, and low blood cell levels. Chloroquine is a member of the drug class 4-aminoquinoline. As an antimalarial, it works against the asexual form of the malaria parasite in the stage of its life cycle within the red blood cell. How it works in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus is unclear.

Chloroquine was discovered in 1934 by Hans Andersag. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system. It is available as a generic medication. The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.04. In the United States, it costs about US$5.30 per dose.

Medical uses

Malaria

Distribution of malaria in the world:

♦ Elevated occurrence of chloroquine- or multi-resistant malaria

♦ Occurrence of chloroquine-resistant malaria

♦ No Plasmodium falciparum or chloroquine-resistance

♦ No malaria

♦ Elevated occurrence of chloroquine- or multi-resistant malaria

♦ Occurrence of chloroquine-resistant malaria

♦ No Plasmodium falciparum or chloroquine-resistance

♦ No malaria

Chloroquine has been used in the treatment and prevention of malaria from Plasmodium vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae. It is generally not used for Plasmodium falciparum as there is widespread resistance to it.

Chloroquine has been extensively used in mass drug administrations,

which may have contributed to the emergence and spread of resistance.

It is recommended to check if chloroquine is still effective in the

region prior to using it. In areas where resistance is present, other antimalarials, such as mefloquine or atovaquone, may be used instead. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend against treatment of malaria with chloroquine alone due to more effective combinations.

Amebiasis

In treatment of amoebic liver abscess, chloroquine may be used instead of or in addition to other medications in the event of failure of improvement with metronidazole or another nitroimidazole within 5 days or intolerance to metronidazole or a nitroimidazole.

Rheumatic disease

As it mildly suppresses the immune system, chloroquine is used in some autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus.

Side effects

Side effects

include blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, headache,

diarrhea, swelling legs/ankles, shortness of breath, pale

lips/nails/skin, muscle weakness, easy bruising/bleeding, hearing and

mental problems.

- Unwanted/uncontrolled movements (including tongue and face twitching)

- Deafness or tinnitus

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps

- Headache

- Mental/mood changes (such as confusion, personality changes, unusual thoughts/behavior, depression, feeling being watched, hallucinating)

- Signs of serious infection (such as high fever, severe chills, persistent sore throat)

- Skin itchiness, skin color changes, hair loss, and skin rashes

- Chloroquine-induced itching is very common among black Africans (70%), but much less common in other races. It increases with age, and is so severe as to stop compliance with drug therapy. It is increased during malaria fever; its severity is correlated to the malaria parasite load in blood. Some evidence indicates it has a genetic basis and is related to chloroquine action with opiate receptors centrally or peripherally

- Unpleasant metallic taste

- This could be avoided by "taste-masked and controlled release" formulations such as multiple emulsions

- Chloroquine retinopathy

- Electrocardiographic changes

- This manifests itself as either conduction disturbances (bundle-branch block, atrioventricular block) or Cardiomyopathy – often with hypertrophy, restrictive physiology, and congestive heart failure. The changes may be irreversible. Only two cases have been reported requiring heart transplantation, suggesting this particular risk is very low. Electron microscopy of cardiac biopsies show pathognomonic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies.

- Pancytopenia, aplastic anemia, reversible agranulocytosis, low blood platelets, neutropenia

Pregnancy

Chloroquine has not been shown to have any harmful effects on the

fetus when used in the recommended doses for malarial prophylaxis.

Small amounts of chloroquine are excreted in the breast milk of

lactating women. However, this drug can be safely prescribed to infants,

the effects are not harmful. Studies with mice show that radioactively

tagged chloroquine passed through the placenta rapidly and accumulated

in the fetal eyes which remained present five months after the drug was

cleared from the rest of the body. Women who are pregnant or planning on getting pregnant are still advised against traveling to malaria-risk regions.

Elderly

There is not enough evidence to determine whether chloroquine is safe

to be given to people aged 65 and older. Since it is cleared by the

kidneys, toxicity should be monitored carefully in people with poor

kidney functions.

Drug interactions

Chloroquine has a number of drug–drug interactions that might be of clinical concern:

- Ampicillin- levels may be reduced by chloroquine;

- Antacids- may reduce absorption of chloroquine;

- Cimetidine- may inhibit metabolism of chloroquine; increasing levels of chloroquine in the body;

- Cyclosporine- levels may be increased by chloroquine; and

- Mefloquine- may increase risk of convulsions.

Overdose

Chloroquine, in overdose, has a risk of death of about 20%. It is rapidly absorbed from the gut with an onset of symptoms generally within an hour. Symptoms of overdose may include sleepiness, vision changes, seizures, stopping of breathing, and heart problems such as ventricular fibrillation and low blood pressure. Low blood potassium may also occur.

While the usual dose of chloroquine used in treatment is 10

mg/kg, toxicity begins to occur at 20 mg/kg, and death may occur at 30

mg/kg. In children as little as a single tablet can cause problems.

Treatment recommendations include early mechanical ventilation, cardiac monitoring, and activated charcoal. Intravenous fluids and vasopressors may be required with epinephrine being the vasopressor of choice. Seizures may be treated with benzodiazepines. Intravenous potassium chloride may be required, however this may result in high blood potassium later in the course of the disease. Dialysis has not been found to be useful.

Pharmacology

Chloroquine's absorption of the drug is rapid. It is widely distributed in body tissues. Its protein binding is 55%. Its metabolism is partially hepatic, giving rise to its main metabolite, desethylchloroquine. Its excretion is ≥50% as unchanged drug in urine, where acidification of urine increases its elimination. It has a very high volume of distribution, as it diffuses into the body's adipose tissue.

Accumulation of the drug may result in deposits that can lead to blurred vision and blindness. It and related quinines have been associated with cases of retinal toxicity, particularly when provided at higher doses for longer times. With long-term doses, routine visits to an ophthalmologist are recommended.

Chloroquine is also a lysosomotropic agent, meaning it accumulates preferentially in the lysosomes of cells in the body. The pKa for the quinoline nitrogen of chloroquine is 8.5, meaning it is about 10% deprotonated at physiological pH (per the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation). This decreases to about 0.2% at a lysosomal pH of 4.6.

Because the deprotonated form is more membrane-permeable than the

protonated form, a quantitative "trapping" of the compound in lysosomes

results.

Mechanism of action

Medical quinolines

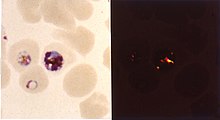

Malaria

Hemozoin formation in P. falciparum: many antimalarials are strong inhibitors of hemozoin crystal growth.

The lysosomotropic character of chloroquine is believed to account

for much of its antimalarial activity; the drug concentrates in the

acidic food vacuole of the parasite and interferes with essential

processes. Its lysosomotropic properties further allow for its use for in vitro experiments pertaining to intracellular lipid related diseases, autophagy, and apoptosis.

Inside red blood cells, the malarial parasite, which is then in its asexual lifecycle stage, must degrade hemoglobin

to acquire essential amino acids, which the parasite requires to

construct its own protein and for energy metabolism. Digestion is

carried out in a vacuole of the parasitic cell.

Hemoglobin is composed of a protein unit (digested by the

parasite) and a heme unit (not used by the parasite). During this

process, the parasite releases the toxic and soluble molecule heme.

The heme moiety consists of a porphyrin ring called

Fe(II)-protoporphyrin IX (FP). To avoid destruction by this molecule,

the parasite biocrystallizes heme to form hemozoin, a nontoxic molecule. Hemozoin collects in the digestive vacuole as insoluble crystals.

Chloroquine enters the red blood cell by simple diffusion,

inhibiting the parasite cell and digestive vacuole. Chloroquine then

becomes protonated (to CQ2+), as the digestive vacuole is known to be

acidic (pH 4.7); chloroquine then cannot leave by diffusion. Chloroquine

caps hemozoin molecules to prevent further biocrystallization

of heme, thus leading to heme buildup. Chloroquine binds to heme (or

FP) to form the FP-chloroquine complex; this complex is highly toxic to

the cell and disrupts membrane function. Action of the toxic

FP-chloroquine and FP results in cell lysis and ultimately parasite cell

autodigestion. Parasites that do not form hemozoin are therefore resistant to chloroquine.

Resistance in malaria

Since the first documentation of P. falciparum chloroquine

resistance in the 1950s, resistant strains have appeared throughout East

and West Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America. The effectiveness

of chloroquine against P. falciparum has declined as resistant

strains of the parasite evolved. They effectively neutralize the drug

via a mechanism that drains chloroquine away from the digestive vacuole.

Chloroquine-resistant cells efflux chloroquine at 40 times the rate of

chloroquine-sensitive cells; the related mutations trace back to

transmembrane proteins of the digestive vacuole, including sets of

critical mutations in the P. falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) gene. The mutated protein, but not the wild-type transporter, transports chloroquine when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (frog's eggs) and is thought to mediate chloroquine leak from its site of action in the digestive vacuole. Resistant parasites also frequently have mutated products of the ABC transporter P. falciparum multidrug resistance (PfMDR1) gene, although these mutations are thought to be of secondary importance compared to Pfcrt. Verapamil, a Ca2+

channel blocker, has been found to restore both the chloroquine

concentration ability and sensitivity to this drug. Recently, an altered

chloroquine-transporter protein CG2 of the parasite has been related to

chloroquine resistance, but other mechanisms of resistance also appear

to be involved.

Research on the mechanism of chloroquine and how the parasite has

acquired chloroquine resistance is still ongoing, as other mechanisms of

resistance are likely.

Other agents which have been shown to reverse chloroquine resistance in malaria are chlorpheniramine, gefitinib, imatinib, tariquidar and zosuquidar.

Antiviral

Chloroquine has antiviral effects.

It increases late endosomal and lysosomal pH, resulting in impaired

release of the virus from the endosome or lysosome – release of the

virus requires a low pH. The virus is therefore unable to release its

genetic material into the cell and replicate.

Chloroquine also seems to act as a zinc ionophore, that allows

extracellular zinc to enter the cell and inhibit viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

Other

Against rheumatoid arthritis, it operates by inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation, phospholipase A2, antigen presentation in dendritic cells, release of enzymes from lysosomes, release of reactive oxygen species from macrophages, and production of IL-1.

History

In Peru, the indigenous people extracted the bark of the Cinchona tree (Cinchona officinalis)

and used the extract to fight chills and fever in the seventeenth

century. In 1633 this herbal medicine was introduced in Europe, where it

was given the same use and also began to be used against malaria. The quinoline antimalarial drug quinine was isolated from the extract in 1820, and chloroquine is an analogue of this.

Chloroquine was discovered in 1934, by Hans Andersag and coworkers at the Bayer laboratories, who named it Resochin. It was ignored for a decade, because it was considered too toxic for human use. Instead, the DAK

used the chloroquine analogue 3-methyl-chloroquine, known as Sontochin.

After Allied forces arrived in Tunis, Sontochin fell into the hands of

Americans, who sent the material back to the United States for analysis,

leading to renewed interest in chloroquine.

United States government-sponsored clinical trials for antimalarial

drug development showed unequivocally that chloroquine has a significant

therapeutic value as an antimalarial drug. It was introduced into

clinical practice in 1947 for the prophylactic treatment of malaria.

Society and culture

Resochin tablet package

Formulations

Chloroquine comes in tablet form as the phosphate, sulfate, and

hydrochloride salts. Chloroquine is usually dispensed as the phosphate.

Names

Brand names include Chloroquine FNA, Resochin, Dawaquin, and Lariago.

Other animals

Chloroquine, in various chemical forms, is used to treat and control

surface growth of anemones and algae, and many protozoan infections in

aquariums, e.g. the fish parasite Amyloodinium ocellatum.

Research

COVID-19

As of 8 April 2020, there is limited evidence to support the use of chloroquine in treating COVID-19. In January 2020, during the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic, Chinese medical researchers stated that exploratory research into chloroquine seemed to have "fairly good inhibitory effects" on the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Requests to start clinical testing were submitted. Use, however, is only recommended in the setting of an approved trial or under the details outlined by Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered Interventions.

Chloroquine has been approved by Chinese, South Korean and

Italian health authorities for the experimental treatment of COVID-19. These agencies noted contraindications for people with heart disease or diabetes.

Health experts warned against the misuse of the

non-pharmaceutical versions of chloroquine phosphate after a husband and

wife consumed a fish tank antiparasitic containing chloroquine phosphate on March 24, with the intention of it being prophylaxis against COVID-19. One of them died and the other was hospitalized. Chloroquine has a relatively narrow therapeutic index and it can be toxic at levels not much higher than those used for treatment—which raises the risk of inadvertent overdose. On 27 March 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidance, "do not use chloroquine phosphate intended for fish as treatment for COVID-19 in humans".

On March 28, 2020 the FDA authorized the use of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). The treatment has not been approved by the FDA.

The experimental treatment is authorized only for emergency use for

people who are hospitalized but not able to receive treatment in a

clinical trial.

On 1 April 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) issued guidance that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are only to be used in clinical trials or emergency use programs.

A study of chloroquine in 81 hospitalized people in Brazil was

halted. About 40 people with coronavirus got a 600 milligram dose over

10 days. By the sixth day of treatment, 11 of them had died, leading to

an immediate end to the high-dose segment of the trial. About 40 other

people received a dose of 450 milligrams of chloroquine twice daily for

five days.

In anticipation of product shortages, the FDA issued

product-specific guidance for chloroquine phosphate and for

hydroxychloroquine sulfate for generic drug manufacturers.

Other viruses

Chloroquine had been also proposed as a treatment for SARS, with in vitro tests inhibiting the SARS-CoV virus.

In October 2004, a group of researchers at the Rega Institute for

Medical Research published a report on chloroquine, stating that

chloroquine acts as an effective inhibitor of the replication of the

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in vitro.

Chloroquine was being considered in 2003, in pre-clinical models as a potential agent against chikungunya fever.

Other

The radiosensitizing and chemosensitizing properties of chloroquine are beginning to be exploited in anticancer strategies in humans. In biomedicinal science, chloroquine is used for in vitro experiments to inhibit lysosomal degradation of protein products.