Environmental racism is a concept in the environmental justice movement, which developed in the United States throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The term is used to describe environmental injustice that occurs within a racialized context both in practice and policy. In the United States, environmental racism criticizes inequalities between urban and exurban areas after white flight. Internationally, environmental racism can refer to the effects of the global waste trade, like the negative health impact of the export of electronic waste to China from developed countries.

Examples by region

North America

Native American reservations

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Trail of Tears may be considered early examples of environmental racism in the United States. As a result of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, by 1850, all tribes east of the Mississippi had been removed to western lands, essentially confining them to "lands that were too dry, remote, or barren to attract the attention of settlers and corporations." During World War II, military facilities were often located conterminous to reservations, leading to a situation in which "a disproportionate number of the most dangerous military facilities are located near Native American lands." A study analyzing the approximately 3,100 counties in the continental United States found that Native American lands are positively associated with the count of sites with unexploded ordnance deemed extremely dangerous. The study also found that the risk assessment code (RAC) used to measure dangerousness of sites with unexploded ordnance can sometimes conceal how much of a threat these sites are to Native Americans. The hazard probability, or probability that a hazard will harm people or ecosystems, is sensitive to the proximity of public buildings such as schools and hospitals. These parameters neglect elements of tribal life such as subsistence consumption, ceremonial use of plants and animals, and low population densities. Because these tribal-unique factors are not considered, Native American lands can often receive low-risk scores, despite threat to their way of life. The hazard probability does not take Native Americans into account when considering the people or ecosystems that could be harmed. Locating military facilities coterminous to reservations lead to a situation in which “a disproportionate number of the most dangerous military facilities are located near Native American lands.”

More recently, Native American lands have been used for waste disposal and illegal dumping by the US and multinational corporations. The International Tribunal of Indigenous People and Oppressed Nations, convened in 1992 to examine the history of criminal activity against indigenous groups in the United States, and published a Significant Bill of Particulars outlining grievances indigenous peoples had with the US. This included allegations that the US "deliberately and systematically permitted, aided, and abetted, solicited and conspired to commit the dumping, transportation, and location of nuclear, toxic, medical, and otherwise hazardous waste materials on Native American territories in North America and has thus created a clear and present danger to the health, safety, and physical and mental well-being of Native American People."

An ongoing issue for Native Americans activists is the Dakota Access Pipeline. The pipeline was proposed to start in North Dakota and travel to Illinois. Although it does not cross directly on a reservation, the pipeline is under scrutiny because it passes under a section of the Missouri river which is the main drinking water source for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Pipelines are known to break, with the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) reporting more than 3,300 leak and rupture incidents for oil and gas pipelines since 2010. The pipeline also traverses a sacred burial ground for the Standing Rock Sioux. The Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe voiced concerns related to sacred sites and archaeological materials. These concerns were ignored. President Barack Obama revoked the permit for the project in December 2016 and ordered a study on rerouting the pipeline. President Donald Trump reversed this order and authorized the completion of the pipeline. In 2017, Judge James Boasberg sided with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, citing the US Army Corps of Engineers failure to complete a study on the environmental impact of an oil spill in Lake Oahe when it first approved construction. A new environmental study was ordered and released in October 2018, but the pipeline remained operational. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe rejected the study, believing it fails to address many of their concerns. There are still ongoing litigation efforts by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe opposing the Dakota Access Pipeline in an effort to shut it down permanently.

United States of America

In the United States, the first report to draw a relationship between race, income, and risk of exposure to pollutants was the Council of Environmental Quality's "Annual Report to the President" in 1971, in response to toxic waste dumping in an African American community in Warren County, NC. After protests in Warren County, North Carolina, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) issued a report on the case in 1983, and the United Church of Christ (UCC) commissioned a report exploring the concept in 1987 drawing a connection between race and the placement of the hazardous waste facilities. The outcry in Warren County was an important event in spurring minority, grassroots involvement in the environmental justice movement by addressing cases of environmental racism.

The US Government Accountability Office study in response to the 1982 protests against the PCB landfill in Warren County was among the first groundbreaking studies that drew correlations between the racial and economic background of communities and the location of hazardous waste facilities. However, the study was limited in scope by only focusing on off-site hazardous waste landfills in the Southeastern United States. In response to this limitation the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ) directed a comprehensive national study on demographic patterns associated with the location of hazardous waste sites.

The CRJ national study conducted two examinations of areas surrounding commercial hazardous waste facilities and the location of uncontrolled toxic waste sites. The first study examined the association between race and socio-economic status and the location of commercial hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities. After statistical analysis, the first study concluded that "the percentage of community residents that belonged to a racial or ethnic group was a stronger predictor of the level of commercial hazardous waste activity than was household income, the value of the homes, the number of uncontrolled waste sites, or the estimated amount of hazardous wastes generated by industry". The second study examined the presence of uncontrolled toxic waste sites in ethnic and racial minority communities, and found that 3 out of every 5 African and Hispanic Americans lived in communities with uncontrolled waste sites. Other studies found race to be the most influential variable in predicting where waste facilities were located.

From the reports on environmental racism in Warren County, NC, the accumulation of studies and reports on cases of environmental racism and injustices garnered increased public attention in the US. Eventually this led to President Bill Clinton's 1994 Executive Order 12898 which directed agencies to develop a strategy that manages environmental justice, but not every federal agency has fulfilled this order to date. This was a historical step in addressing environmental injustice on a policy level, especially within a predominantly white-dominated environmentalism movement; however, the effectiveness of the Order is noted mainly in its influence on states as Congress never passed a bill making Clinton's Executive Order law. The issuance of the Order propelled states into action as many states began to require relevant agencies to develop strategies and programs that would identify and address environmental injustices being perpetrated at the state or local level.

In 2005, during George W. Bush's administration, there was an attempt to remove the premise of racism from the Order. EPA's Administrator Stephen Johnson wanted to redefine the Order's purpose to shift from protecting low income and minority communities that may be disadvantaged by government policies to all people. President Barack Obama's appointment of Lisa Jackson as EPA Administrator and the issuance of Memorandum of Understanding on Environmental Justice and Executive Order 12898 established a recommitment to environmental justice. The fight against environmental racism faced some setbacks with the election of President Trump. Under Trump's administration, there was a mandated decrease of EPA funding accompanied by a rollback on regulations which has left many underrepresented communities vulnerable.

As a result of the placement of hazardous waste facilities, minority populations experience greater exposure to harmful chemicals and suffer from health outcomes that affect their ability at work and in schools. A comprehensive study of particulate emissions across the United States, published in 2018, found that Blacks were exposed to 54% more particulate matter emissions (soot) than the average American. Faber and Krieg found a correlation between higher air pollution exposure and low performance in schools and found that 92% of children at five Los Angeles public schools with the poorest air quality were of a minority background. School systems for communities heavily populated with minority families tend to provide "unequal educational opportunities" in comparison to school systems in predominantly white neighborhoods. Pollution consequently presents itself in these communities due to societal factors such as "underfunded schools, income inequality, and myriad egregious denials of institutional support" within the African American community. In a study supporting the term of environmental racism, it was shown in the American Mid-Atlantic and American North-East that African Americans were exposed to 61% of particulate matter, while Latinos were exposed to 75%, and Asians were exposed to 73%. Overall, these populations experience 66% more pollution exposure from particulate matter than the white population.

When environmental racism became acknowledged in the US society, it stimulated the environmental justice social movement that gained wave throughout the 1970s and 1980s in the US. Historically, the term environmental racism is tied to environmental justice movement. However, this has changed with time to the extent it is believed to lack any associations with the movement. Grassroots organizations and campaigns have sprung up in response to this environmental racism with these groups mainly demanding the inclusion of minorities when it comes to policy making involving the environment. It is also worth noting that this concept is international despite being coined in the US. A perfect example is when the United States exported its hazardous wastes to the poor nations in the Global South because they knew that these countries had lax environmental regulations and safety practices. Marginalized communities are usually at risk of environmental racism because they resource and means to oppose the large companies that dump these dangerous wastes.

There are specific examples of environmental racism across the US, and perpetuates of environmental racism are often engrained in day to day work and living conditions. The city of Chicago, Illinois, has had difficulties around industry and its impacts on minority populations, especially the African American community. Several coal plants in the region have been implicated in the poor health of their local communities, a correlation exacerbated by the fact that 34% of adults in those communities do not have health care coverage. The state of Louisiana has also faced several issues striking balance between industry presence, natural disaster relief, and community health. Pre-existing racial disparities in wealth within New Orleans worsened the outcome of Hurricane Katrina for minority populations.

Institutionalized racial segregation of neighborhoods meant minority members were more likely to live in low-lying areas vulnerable to flooding. Additionally, hurricane evacuation plans relied heavily on the use of cars and did not prepare for people who relied on public transportation. Because minority populations are less likely to own cars, some people had no choice but to stay behind, while white majority communities escaped. Additionally, Cancer Alley, a row of chemical plants in Louisiana, has been cited as one of the causes of disproportionate health impacts in the city. Flint, Michigan, a city that is 57% black and notably impoverished, was found in April 2014 to be drinking water that contained enough lead to meet the Environmental Protection Agency.

Overall, the US has worked to reduce environmental racism with municipality changes. These policies help develop further change. Some cities and counties have taken advantage of environmental justice policies and applied it to the public health sector.

Mexico

On November 19, 1984, the San Juanico disaster caused thousands of deaths and roughly a million injuries in poor surrounding neighborhoods. The disaster occurred at the PEMEX liquid propane gas plant in a densely populated area of Mexico City. The close proximity of illegally built houses that did not meet regulations worsened the effects of the explosion.

The Cucapá are a group of indigenous people that live near the U.S.-Mexico border, mainly in Mexico but some in Arizona as well. For many generations, fishing on the Colorado River was the Cucapá's main means of subsistence. In 1944, the United States and Mexico signed a treaty that effectively awarded the United States rights to about 90% of the water in the Colorado River, leaving Mexico with the remaining 10%. Over the last few decades the Colorado River has mostly dried up south of the border, presenting many challenges for people such as the Cucapá. Shaylih Meuhlmann, author of the ethnography Where the River Ends: Contested Indigeneity in the Mexican Colorado Delta, gives a first-hand account of the situation from Meuhlmann's point of view as well as many accounts from the Cucapá themselves. In addition to the Mexican portion of the Colorado River being left with a small fraction of the overall available water, the Cucapá are stripped of the right to fish on the river, the act being made illegal by the Mexican government in the interest of preserving the river's ecological health. The Cucapá are, thus, living without access to sufficient natural sources of freshwater as well as without their usual means of subsistence. The conclusion drawn in many such cases is that the negotiated water rights under the US-Mexican treaty that lead to the massive disparity in water allotments between the two countries boils down to environmental racism.

1,900 maquiladoras are found near the US-Mexico border. Maquiladoras are companies that are usually owned by foreign entities and import raw materials, pay workers in Mexico to assemble them, and ship the finish products overseas to be sold. While Maquiladoras provide jobs, they often pay very little. These plants also bring pollution to rural Mexican towns, creating health impacts for the poor families that live nearby.

In Mexico, industrial extraction of oil, mining, and gas, as well as the mass removal of slowly renewable resources such as aquatic life, forests, and crops. Legally, the state owns natural resources, but is able to grant concessions to industry through the form of taxes paid. In recent decades, a shift towards refocusing these tax dollars accumulated on the communities most impacted by the health, social, and economic impacts of extractivism has taken place. However, many indiginous and rural community leaders argue that they ought to consent to companies extracting and polluting their resources, rather than be paid reparations after the fact.

Canada

In Canada, progress is being made to address environmental racism (especially in Nova Scotia's Africville community) with the passing of Bill 111, An Act to Address Environmental Racism in the Nova Scotia Legislature. Still, however, indigenous communities such as the Aamjiwnaang First Nation continue to be harmed by pollution from the Canadian chemical industry centered in Southeast Ontario.

Forty percent of Canada’s petrochemical industry is packed into a 15-square mile radius of Sarnia, Ontario. The population is predominantly indiginous, where the Aamjiwnaang reservation houses around 850 First Nation individuals. Since 2002, coalitions of indiginous individuals have fought the disproportionate concentration of pollution in their neighborhood.

Europe

France

Exporting toxic wastes to countries in the Global South is one form of environmental racism that occurs on an international basis. In one alleged instance, the French aircraft carrier Clemenceau was prohibited from entering Alang, an Indian ship-breaking yard, due to a lack of clear documentation about its toxic contents. French President Jacques Chirac ultimately ordered the carrier, which contained tons of hazardous materials including asbestos and PCBs, to return to France.

United Kingdom

In the UK environmental racism (or also climate racism) has been called out by multiple action groups such as the Wretched of the Earth call out letter in 2015 and Black Lives Matter in 2016.

Romani people, Eastern Europe

Predominantly living in Central and Eastern Europe, with pockets of communities in the Americas and Middle East, the ethnic Romani people have been subjected to environmental exclusion. Often referred to as gypsies or the gypsy threat, the Romani people of Eastern Europe mostly live under the poverty line in shanty towns or slums. Facing issues such as long term exposure to harmful toxins given their locations to waste dumps and industrial plants, along with being refused environmental assistance like clean water and sanitation, the Romani people have been facing racism via environmental means. Many countries such has Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary have tried to implement environmental protection initiatives across their respected countries, however most have failed due to "addressing the conditions of Roma communities have been framed through an ethnic lens as “Roma issues." Only recently has some form of environmental justice for the Romani people come to light. Seeking environmental justice in Europe, the Environmental Justice Program is now working with human rights organizations to help fight environmental racism.

It is important to note that in the "Discrimination in the EU in 2009" report, conducted by the European Commission, "64% of citizens with Roma friends believe discrimination is widespread, compared to 61% of citizens without Roma friends."

Oceania

Australia

The Australian Environmental Justice (AEJ) is a multidisciplinary organization which is closely partnered with Friends of the Earth Australia (FoEA). The AEJ focuses on recording and remedying the effects of environmental injustice throughout Australia. The AEJ has addressed issues which include "production and spread of toxic wastes, pollution of water, soil and air, erosion and ecological damage of landscapes, water systems, plants and animals". The project looks for environmental injustices that disproportionately affect a group of people or impact them in a way they did not agree to.

The Western Oil Refinery started operating in Bellevue, Western Australia in 1954. It was permitted rights to operate in Bellevue by the Australian government in order to refine cheap and localized oil. In the decades following, many residents of Bellevue claimed they felt respiratory burning due to the inhalation of toxic chemicals and nauseating fumes. Lee Bell from Curtin University and Mariann Lloyd-Smith from the National Toxic Network in Australia stated in their article, "Toxic Disputes and the Rise of Environmental Justice in Australia" that "residents living close to the site discovered chemical contamination in the ground- water surfacing in their back yards". Under immense civilian pressure, the Western Oil Refinery (now named Omex) stopped refining oil in 1979. Years later, citizens of Bellevue formed the Bellevue Action Group (BAG) and called for the government to give aid towards the remediation of the site. The government agreed and $6.9 million was allocated to clean up the site. Remediation of site began in April 2000.

Papua New Guinea

Starting production in 1972, the Panguna mine in Papua New Guinea has been a source of environmental racism. Although closed since 1989 due to conflict on the island, the indigenous peoples (Bougainvillean) have suffered both economically and environmentally from the creation of the mine. Terrance Wesley-Smith and Eugene Ogan, University of Hawaii and University of Minnesota respectively, stated that the Bougainvillean's "were grossly disadvantaged from the beginning and no subsequent renegotiation has been able to remedy the situation". These indigenous people faced issues such as losing land which could have been used for agricultural practices for the Dapera and Moroni villages, undervalued payment for the land, poor relocation housing for displaced villagers and significant environmental degradation in the surrounding areas.

Asia

China

From the mid-1990s until about 2001, it is estimated that some 50 to 80 percent of the electronics collected for recycling in the western half of the United States was being exported for dismantling overseas, predominantly to China and Southeast Asia. This scrap processing is quite profitable and preferred due to an abundant workforce, cheap labour, and lax environmental laws.

Guiyu, China is one of the largest recycling sites for e-waste, where heaps of discarded computer parts rise near the riverbanks and compounds, such as cadmium, copper, lead, PBDEs, contaminate the local water supply. Water samples taken by the Basel Action Network in 2001 from the Lianjiang River contained lead levels 190 times higher than WHO safety standards. Despite contaminated drinking water, residents continue to use contaminated water over expensive trucked-in supplies of drinking water. Nearly 80 percent of children in the e-waste hub of Guiyu, China, suffer from lead poisoning, according to recent reports. Before being used as the destination of electronic waste, most of Guiyu was composed of small farmers who made their living in the agriculture business. However, farming has been abandoned for more lucrative work in scrap electronics. "According to the Western press and both Chinese university and NGO researchers, conditions in these workers' rural villages are so poor that even the primitive electronic scrap industry in Guiyu offers an improvement in income".

Researchers have found that as rates of hazardous air pollution increase in China, the public has mobilized to implement measures to curb detrimental impacts. Areas with ethnic minorities and western regions of the country tend to carry disproportionate environmental burdens.

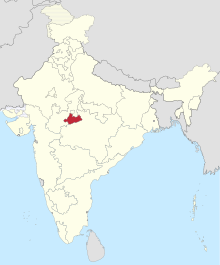

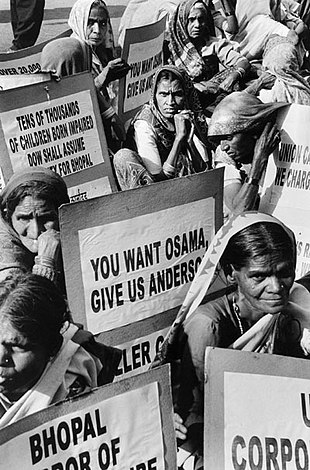

India

Union Carbide Corporation, is the parent company of Union Carbide India Limited which outsources its production to an outside country. Located in Bhopal, India, Union Carbide India Limited primarily produced the chemical methyl isocyanate used for pesticide manufacture. On December 3, 1984, a cloud of methyl isocyanate leaked as a result of the toxic chemical mixing with water in the plant in Bhopal. Approximately 520,000 people were exposed to the toxic chemical immediately after the leak. Within the first 3 days after the leak an estimated 8,000 people living within the vicinity of the plant died from exposure to the methyl isocyanate. Some people survived the initial leak from the factory, but due to improper care and improper diagnoses many have died. As a consequence of improper diagnoses, treatment may have been ineffective and this was precipitated by Union Carbide refusing to release all the details regarding the leaked gases and lying about certain important information. The delay in supplying medical aid to the victims of the chemical leak made the situation for the survivors even worse. Many today are still experiencing the negative health impacts of the methyl isocyanate leak, such as lung fibrosis, impaired vision, tuberculosis, neurological disorders, and severe body pains.

The operations and maintenance of the factory in Bhopal contributed to the hazardous chemical leak. The storage of huge volumes of methyl isocyanate in a densely inhabited area, was in contravention with company policies strictly practiced in other plants. The company ignored protests that they were holding too much of the dangerous chemical for one plant and built large tanks to hold it in a crowded community. Methyl isocyanate must be stored at extremely low temperatures, but the company cut expenses to the air conditioning system leading to less than optimal conditions for the chemical.

Additionally, Union Carbide India Limited never created disaster management plans for the surrounding community around the factory in the event of a leak or spill. State authorities were in the pocket of the company and therefore did not pay attention to company practices or implementation of the law. The company also cut down on preventive maintenance staff to save money.

South America

Ecuador

Due to their lack of environmental laws, emerging countries like Ecuador have been subjected to environmental pollution, sometimes causing health problems, loss of agriculture, and poverty. In 1993, 30,000 Ecuadorians, which included Cofan, Siona, Huaorani, and Quichua indigenous people, filed a lawsuit against Texaco oil company for the environmental damages caused by oil extraction activities in the Lago Agrio oil field. After handing control of the oil fields to an Ecuadorian oil company, Texaco did not properly dispose of its hazardous waste, causing great damages to the ecosystem and crippling communities. Additionally, UN experts have said that Afro-Ecuadorians and other people of African descent in Ecuador have faced greater challenges than other groups in accessing clean water, with minimal response from the State.

Chile

Beginning in the late 15th century when European explorers began sailing to the New World, the violence towards and oppression of indigenous populations have had lasting effects to this day. The Mapuche-Chilean land conflict has roots dating back several centuries. When the Spanish went to conquer parts of South America, the Mapuche were one of the only indigenous groups to successfully resist Spanish domination and maintain their sovereignty. Moving forward, relations between the Mapuche and the Chilean state declined into a condition of malice and resentment. Chile won its independence from Spain in 1818 and, wanting the Mapuche to assimilate into the Chilean state, began crafting harmful legislation that targeted the Mapuche. The Mapuche have based their economy, both historically and presently, on agriculture. By the mid-19th century, the state resorted to outright seizure of Mapuche lands, forcefully appropriating all but 5% of Mapuche lineal lands. An agrarian economy without land essentially meant that the Mapuche no longer had their means of production and subsistence. While some land has since been ceded back to the Mapuche, it is still a fraction of what the Mapuche once owned. Further, as the Chilean state has attempted to rebuild its relationship with the Mapuche community, the connection between the two is still strained by the legacy of the aforementioned history.

Today, the Mapuche people are the largest population of indigenous people in Chile, with 1.5 million people accounting for over 90% of the country's indigenous population.

The Andes

Extracitivism, or the process of humans removing natural, raw resources from land to be used in product manufacturing, can have detrimental environmental and social repercussions. Research analyzing environmental conflicts in four Andean countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia) found that conflicts tend to disproportionately affect indigenous populations and those with Afro-descent, and peasant communities. These conflicts can arise as a result of shifting economic patterns, land use policies, and social practices due to extractivist industries.

Haiti

Legacies of racism exist in Haiti, and affect the way that food grown by peasants domestically is viewed compared to foreign food. Racially coded hierarchies are associated with food that differs in origin - survey respondents reported that food such as millet and root crops are associated with negative connotations, while foreign-made food such as corn flakes and spaghetti are associated with positive connotations. This reliance on imports over domestic products reveals how racism ties to commercial tendencies - a reliance on imports can increase costs, fossil fuel emissions, and further social inequality as local farmers loose business.

Africa

Nigeria

In Nigeria, near the Niger Delta, cases of oil spills, burning of toxic waste, and urban air pollution are problems in more developed areas. In the early 1990s, Nigeria was among the 50 nations with the world's highest levels of carbon dioxide emissions, which totaled 96,500 kilotons, a per capita level of 0.84 metric tons. The UN reported in 2008 that carbon dioxide emissions in Nigeria totaled 95,194 kilotons.

Numerous webpages were created in support of the Ogoni people, who are indigenous to Nigeria's oil-rich Delta region. Sites were used to protest the disastrous environmental and economic effects of Shell Oil drilling, to urge the boycotting of Shell Oil, and to denounce human rights abuses by the Nigerian government and by Shell. The use of the Internet in formulating an international appeal intensified dramatically after the Nigerian government's November 1995 execution of nine Ogoni activists, including Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was one of the founders of the nonviolent Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP).

South Africa

The linkages between the mining industry and the negative impacts it has on community and individual health has been studied and well-documented by a number of organizations worldwide. Health implications of living in proximity to mining operations include effects such as pregnancy complications, mental health issues, various forms of cancer, and many more. During the Apartheid period in South Africa, the mining industry grew quite rapidly as a result of the lack of environmental regulation. Communities in which mining corporations operate are usually those with high rates of poverty and unemployment. Further, within these communities, there is typically a divide among the citizens on the issue of whether the pros of mining in terms of economic opportunity outweigh the cons in terms of the health of the people in the community. Mining companies often try to use these disagreements to their advantage by magnifying this conflict. Additionally, mining companies in South Africa have close ties with the national government, skewing the balance of power in their favor while simultaneously excluding local people from many decision-making processes. This legacy of exclusion has had lasting effects in the form of impoverished South Africans bearing the brunt of ecological impacts resulting from the actions of, for example, mining companies. Some argue that to effectively fight environmental racism and achieve some semblance of justice, there must also be a reckoning with the factors that form situations of environmental racism such as rooted and institutionalized mechanisms of power, social relations, and cultural elements.

The term “energy poverty” is used to refer to “a lack of access to adequate, reliable, affordable and clean energy carriers and technologies for meeting energy service needs for cooking and those activities enabled by electricity to support economic and human development”. Numerous communities in South Africa face some sort of energy poverty. South African women are typically in charge of taking care of both the home and the community as a whole. Those in economically impoverished areas not only have to take on this responsibility, but there are numerous other challenges they face. Discrimination on the basis of gender, race, and class are all still present in South African culture. Because of this, women, who are the primary users of public resources in their work at home and for the community, are often excluded from any decision-making about control and access to public resources. The resulting energy poverty forces women to use sources of energy that are expensive and may be harmful both to their own health and that of the environment. Consequently, several renewable energy initiatives have emerged in South Africa specifically targeting these communities and women to correct this situation.

Background

"Environmental Racism" was coined in 1982 by Benjamin Chavis, previous executive director of the United Church of Christ (UCC) Commission for Racial Justice. Chavis's speech addressed hazardous polychlorinated biphenyl waste in the Warren County PCB Landfill, North Carolina. Chavis defined the term as:

racial discrimination in environmental policy making, the enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of color for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the life-threatening presence of poisons and pollutants in our communities, and the history of excluding people of color from leadership of the ecology movements.

The Environmental Justice Movement, began around the same time as the Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement influenced the mobilization of people concerned about their neighborhoods and health by echoing the empowerment and concern associated with political action. Here, the civil rights agenda and the environmental agenda met. The acknowledgement of environmental racism prompted the environmental justice social movement that began in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States. While environmental racism has been historically tied to the environmental justice movement, throughout the years the term has been increasingly disassociated. In response to cases of environmental racism, grassroots organizations and campaigns have brought more attention to environmental racism in policy making and emphasize the importance of having input from minorities in policymaking. Although the term was coined in the US, environmental racism also occurs on the international level. Examples include the exportation of hazardous wastes to poor countries in the Global South with lax environmental policies and safety practices (pollution havens). Marginalized communities that do not have the socioeconomic and political means to oppose large corporations - this puts them at risk to environmentally racist practices that are detrimental to their health. Economic statuses and political positions are crucial factors when looking at environmental problems because they determine where a person lives and their access to resources that could mitigate the impact of environmental hazards. The UCC and US General Accounting Office reports on this case in North Carolina associated locations of hazardous waste sites with poor minority neighborhoods. Chavis and Dr. Robert D. Bullard pointed out institutionalized racism stemming from government and corporate policies that led to environmental racism. Practices included redlining, zoning, and colorblind adaptation planning. Residents experienced environmental racism due to their low socioeconomic status, and lack of political representation and mobility. Expanding the definition in "The Legacy of American Apartheid and Environmental Racism," Dr. Bullard said that environmental racism

"refers to any policy, practice, or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (whether intended or unintended) individuals, groups, or communities based on race or color."

Environmental justice combats barriers preventing equal access to work, recreation, education, religion, and safe neighborhoods. In “Environmentalism of the Poor,” Joan Martinez-Allier writes that environmental justice “points out that economic growth-unfortunately means increased environmental impacts, and it emphasizes geographical displacement of sources and sinks.” Environmental racism is a specific form of environmental injustice with which the underlying cause of said injustice is believed to be race-based.

Causes

There are four factors which lead to environmental racism: lack of affordable land, lack of political power, lack of mobility, and poverty. Cheap land is sought by corporations and governmental bodies. As a result, communities which cannot effectively resist these corporations and governmental bodies and cannot access political power cannot negotiate just costs. Communities with minimized socio-economic mobility cannot relocate. Lack of financial contributions also reduces the communities' ability to act both physically and politically. Chavis defined environmental racism in five categories: racial discrimination in defining environmental policies, discriminatory enforcement of regulations and laws, deliberate targeting of minority communities as hazardous waste dumping sites, official sanctioning of dangerous pollutants in minority communities, and the exclusion of people of color from environmental leadership positions.

Minority communities often do not have the financial means, resources, and political representation to oppose hazardous waste sites. Known as locally unwanted land uses or LULU's, these facilities that benefit the whole community often reduce the quality of life of minority communities. These neighborhoods also may depend on the economic opportunities the site brings and are reluctant to oppose its location at the risk of their health. Additionally, controversial projects are less likely to be sited in non-minority areas that are expected to pursue collective action and succeed in opposing the siting the projects in their area.

Processes such as suburbanization, gentrification, and decentralization lead to patterns of environmental racism. For example, the process of suburbanization (or white flight) consists of non-minorities leaving industrial zones for safer, cleaner, and less expensive suburban locales. Meanwhile, minority communities are left in the inner cities and in close proximity to polluted industrial zones. In these areas, unemployment is high and businesses are less likely to invest in area improvement, creating poor economic conditions for residents and reinforcing a social formation that reproduces racial inequality. Furthermore, the poverty of property owners and residents in a municipality may be taken into consideration by hazardous waste facility developers since areas with depressed real estate values will cut expenses.

Environmental racism has many factors that contribute towards it's discrimination. Green Action references the "cultural norms and values, rules, regulations, behaviors, policies, and decisions" that support the concept of sustainability and wherein environmental racism lies.

Climate change

As the climate has changed progressively over the past several decades, there has been a collision between environmental racism and global climate change. The overlap of these two phenomena, many argue, has disproportionately affected different communities and populations throughout the world due to disparities in socio-economic status. This is especially true in the Global South where, for example, byproducts of global climate change such as increasingly frequent and severe landslides resulting from more heavy rainfall events in Quito, Ecuador force people to also deal with profound socio-economic ramifications like the destruction of their homes or even death. Countries such as Ecuador often contribute relatively little to climate change in terms of metrics like carbon dioxide emissions but have far fewer resources to ward off the negative localized impacts of climate change. This issue occurs globally, where nations in the global south bear the burden of natural disasters and weather extremes despite contributing little to the global carbon footprint.

While people living in the Global South have typically been impacted most by the effects of climate change, people of color in the Global North also face similar situations in several areas. The southeastern part of the United States has experienced a large amount of pollution and minority populations have been hit with the brunt of those impacts. The issues of climate change and communities that are in a danger zone are not limited to North America or the United States either. There are several communities around the world that face the same concern of industry and people who are dealing with its negative impacts in their areas. For example, the work of Desmond D’Sa focused on communities in south Durban where high pollution industries impact people forcibly relocated during the Apartheid.

Environmental racism and climate change coincide with one another. Rising seas affect poor areas such as Kivalina, Alaska, and Thibodaux, Louisiana, and countless other places around the globe. There are many cases of people who have died or are chronically ill from coal plants in Detroit, Memphis, and Kansas City, as well as numerous other areas. Tennessee and West Virginia residents are frequently subject to breathing toxic ash due to blasting in the mountains for mining. Drought, flooding, the constant depletion of land and air quality determine the health and safety of the residents surrounding these areas. Communities of color and low-income status most often feel the brunt of these issues firsthand.

Socioeconomic aspects

Cost benefit analysis

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a process that places a monetary value on costs and benefits to evaluate issues. Environmental CBA aims to provide policy solutions for intangible products such as clean air and water by measuring a consumer's willingness to pay for these goods. CBA contributes to environmental racism through the valuing of environmental resources based on their utility to society. When someone is willing and able to pay more for clean water or air, their society financially benefits society more than when people cannot pay for these goods. This creates a burden on poor communities. Relocating toxic wastes is justified since poor communities are not able to pay as much as a wealthier area for a clean environment. The placement of toxic waste near poor people lowers the property value of already cheap land. Since the decrease in property value is less than that of a cleaner and wealthier area, the monetary benefits to society are greater by dumping the toxic waste in a "low-value" area.

Impacts on health

Environmental racism impacts the health of the communities affected by poor environments. Various factors that can cause health problems include exposure to hazardous chemical toxins in landfills and rivers.

Minority populations are exposed to greater environmental health risks than white people, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). As stated by Greenlining, an advocacy organization based out of Oakland, CA, “[t]he EPA’s National Center for Environmental Assessment found that when it comes to air pollutants that contribute to issues like heart and lung disease, Blacks are exposed to 1.5 times more of the pollutant than whites, while Hispanics were exposed to about 1.2 times the amount of non-Hispanic whites. People in poverty had 1.3 times the exposure of those not in poverty.”

In Defense of Animals claims intensive agriculture affects the health of the communities they are near through pollution and environmental injustice. They claim such areas have waste lagoons that produce hydrogen sulfide, higher levels of miscarriages, birth defects, and disease outbreaks from viral and bacterial contamination of drinking water. These farms are disproportionately placed and largely affect low-income areas and communities of color. Because of the socioeconomic status and location of many of these areas, the people affected cannot easily escape these conditions. This includes exposure to pesticides in agriculture and poorly-managed toxic waste dumping to nearby homes and communities from factories disposing of toxic animal waste.

Intensive agriculture also poses a hazard to its workers through high demand velocities, low pay, poor cleanliness in facilities, and other health risks. The workers employed in intensive agriculture are largely composed of minority races, and these facilities are often near minority communities. Areas that are near factories of this sort are also subjected to contaminated drinking water, toxic fumes, chemical run-off, pollutant particulate matter in the air, and other various harmful risks leading to lessened quality of life and potential disease outbreak.

Reducing environmental racism

Activists have called for "more participatory and citizen-centered conceptions of justice." The environmental justice (EJ) movement and climate justice (CJ) movement address environmental racism in bringing attention and enacting change so that marginalized populations are not disproportionately vulnerable to climate change and pollution. According to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, one possible solution is the precautionary principle, which states that "where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation." Under this principle, the initiator of the potentially hazardous activity is charged with demonstrating the activity's safety. Environmental justice activists also emphasize the need for waste reduction in general, which would act to reduce the overall burden.

Concentrations of ethnic or racial minorities may also foster solidarity, lending support in spite of challenges and providing the concentration of social capital necessary for grassroots activism. Citizens who are tired of being subjected to the dangers of pollution in their communities have been confronting the power structures through organized protest, legal actions, marches, civil disobedience, and other activities.

Racial minorities are often excluded from politics and urban planning (such as sea level rise adaptation planning) so various perspectives of an issue are not included in policy making that may affect these excluded groups in the future. In general, political participation in African American communities is correlated with the reduction of health risks and mortality. Other strategies in battling against large companies include public hearings, the elections of supporters to state and local offices, meetings with company representatives, and other efforts to bring about public awareness and accountability.

In addressing this global issue, activists take to various social media platforms to both raise awareness and call to action. The mobilization and communication between the intersectional grassroots movements where race and environmental imbalance meet has proven to be effective. The movement gained traction with the help of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat among other platforms. Celebrities such as Shailene Woodley, who advocated against the Keystone XL Pipeline, have shared their experiences including that of being arrested for protesting. Social media has allowed for a facilitated conversation between peers and the rest of the world when it comes to social justice issues not only online but in face-to-face interactions correspondingly.

Studies

Studies have been important in drawing associations and public attention by exposing practices that cause marginalized communities to be more vulnerable to environmental health hazards. Deserting the Perpetrator-Victim Model of studying environmental justice issues, the Economic/Environmental Justice Model utilized a sharper lens to study the many complex factors, accompanied to race, that contributes to the act of environmental racism and injustice. For example, Lerner not only revealed the role of race in the division of Diamond and Norco residents, but he also revealed the historical roles of the Shell Oil Company, the slave ancestry of Diamond residents, and of the history of white workers and families that were dependent upon the rewards of Shell. Involvement of outside organizations, such as the Bucket Brigade and Greenpeace, was also considered in the power that the Diamond community had when battling for environmental justice.

In wartimes, environmental racism occurs in ways that the public later learn about through reports. For example, Friends of the Earth International's Environmental Nakba report brings attention to environmental racism that has occurred in the Gaza Strip during the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Some Israeli practices include cutting off three days of water supply to refugee Palestinians and destroying farms.

Besides studies that point out cases of environmental racism, studies have also provided information on how to go about changing regulations and preventing environmental racism from happening. In a study by Daum, Stoler and Grant on e-waste management in Accra, Ghana, the importance of engaging with different fields and organizations such as recycling firms, communities, and scrap metal traders are emphasized over adaptation strategies such as bans on burning and buy-back schemes that have not caused much effect on changing practices.

Studies have also shown that since environmental laws have become prominent in developed countries, companies have moved their waste towards the Global South. Less developed countries have fewer environmental policies and therefore are susceptible to more discriminatory practices. Although this has not stopped activism, it has limited the effects activism has on political restrictions.

Procedural Justice

Current political ideologies surrounding how to make right issues of environmental racism and environmental justice are shifting towards the idea of employing procedural justice. Procedural justice is a concept that dictates the use of fairness in the process of making decisions, especially when said decisions are being made in diplomatic situations such as the allocation of resources or the settling of disagreements. Procedural justice calls for a fair, transparent, impartial decision-making process with equal opportunity for all parties to voice their positions, opinions, and concerns. Rather than just focusing on the outcomes of agreements and the effects those outcomes have on affected populations and interest groups, procedural justice looks to involve all stakeholders throughout the process from planning through implementation. In terms of combating environmental racism, procedural justice helps to reduce the opportunities for powerful actors such as often-corrupt states or private entities to dictate the entire decision-making process and puts some power back into the hands of those who will be directly affected by the decisions being made.

Activism

Activism takes many forms. One form is collective demonstrations or protests, which can take place on a number of different levels from local to international. Additionally, in places where activists feel as though governmental solutions will work, organizations and individuals alike can pursue direct political action. In many cases, activists and organizations will form partnerships both regionally and internationally to gain more clout in pursuit of their goals.

Before the 1970s, communities of color recognized the reality of environmental racism and organized against it. For example, the Black Panther Party organized survival programs that confronted the inequitable distribution of trash in predominantly black neighborhoods. Similarly, the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican revolutionary nationalist organization based in Chicago and New York City, protested pollution and toxic refuse present in their community via the Garbage Offensive program. These and other organizations also worked to confront the unequal distribution of open spaces, toxic lead paint, and healthy food options. They also offered health programs to those affected by preventable, environmentally induced diseases such as tuberculosis. In this way, these organizations serve as precursors to more pointed movements against environmental racism.

Latino ranch laborers composed by Cesar Chavez battled for working environment rights, including insurance from harmful pesticides in the homestead fields of California's San Joaquin Valley. In 1967, African-American understudies rioted in the streets of Houston to battle a city trash dump in their locale which had killed two kids. In 1968, occupants of West Harlem, in New York City, battled unsuccessfully against the siting of a sewage treatment plant in their neighborhood.

Efforts of activism have also been heavily influenced by women and the injustices they face from environmental racism. Women of different races, ethnicities, economic status, age, and gender are disproportionately affected by issues of environmental injustice. Additionally, the efforts made by women have historically been overlooked or challenged by efforts made by men, as the problems women face have been often avoided or ignored. Winona LaDuke is one of many female activists working on environmental issues, in which she fights against injustices faced by indigenous communities. LaDuke was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 2007 for her continuous leadership towards justice.

Artistic Expression

Several artists explore the relationship between environment, power, and culture through creative expression. Art can be used to bring awareness to social issues, including environmental racism.

Be Dammed by Carolina Caycedo utilizes video elements, photographs, paint, and mixed fabrics and papers in order to contextualize the relationship between water and power in Latin America. Her pieces comment on the indigenous view of water signifying connection to nature and to each other, and how the privatization of water impacts communities and ecosystems. The series of works was born following a 2014 “Master Plan” for expansion of extraction from the Magdelena river in Colombia - the plan detailed the construction of 15 hydroelectric dams, and caused a surge of foreign reliance on Colombian resources. Caycedo emphasizes the interconnectedness of processes of colonialism, nature, extraction, and indigeneity in her art.

Allison Janae Hamilton is an artist from the United States who focuses her work on examining the social and political ideas and uses of land and space, particularly in US Southern states. Her work looks at who is affected by a changing climate, as well as the unique vulnerability that certain populations have. Her work relies on videos and photographs to show who is affected by global warming, and how their different lived experiences lend different perspectives to climate issues.

Environmental Reparations

Some scientists and economists have looked into the prospect of Environmental Reparations, or forms of payment made to individuals who are affected by industry presence in some way. Potential groups to be impacted include individuals living in close proximity to industry, victims of natural disasters, and climate refugees who flee hazardous living conditions in their own country. Reparations can take many forms, from direct payouts to individuals, to money set aside for waste-site cleanups, to purchasing air monitors for low income residential neighborhoods, to investing in public transportation, which reduces green house gas emissions. As Dr. Robert Bullard writes,

"Environmental Reparations represent a bridge to sustainability and equity... Reparations are both spiritual and environmental medicine for healing and reconciliation."

Policies and international agreements

The export of hazardous waste to third world countries is another growing concern. Between 1989 and 1994, an estimated 2,611 metric tons of hazardous waste was exported from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries to non-OECD countries. Two international agreements were passed in response to the growing exportation of hazardous waste into their borders. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was concerned that the Basel Convention adopted in March 1989 did not include a total ban on the trans-boundary movement on hazardous waste. In response to their concerns, on January 30, 1991, the Pan-African Conference on Environmental and Sustainable Development adopted the Bamako Convention banning the import of all hazardous waste into Africa and limiting their movement within the continent. In September 1995, the G-77 nations helped amend the Basel Convention to ban the export of all hazardous waste from industrial countries (mainly OECD countries and Lichtenstein) to other countries. A resolution was signed in 1988 by the OA) which declared toxic waste dumping to be a “crime against Africa and the African people”. Soon after, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) passed a resolution that allowed for penalties, such as life imprisonment, to those who were caught dumping toxic wastes.

Globalization and the increase in transnational agreements introduce possibilities for cases of environmental racism. For example, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) attracted US-owned factories to Mexico, where toxic waste was abandoned in the Colonia Chilpancingo community and was not cleaned up until activists called for the Mexican government to clean up the waste.

Environmental justice movements have grown to become an important part of world summits. This issue is gathering attention and features a wide array of people, workers, and levels of society that are working together. Concerns about globalization can bring together a wide range of stakeholders including workers, academics, and community leaders for whom increased industrial development is a common denominator”.

Many policies can be expounded based on the state of human welfare. This occurs because environmental justice is obviously aimed at creating safe, fair, and equal opportunity for communities and to ensure things like redlining do not occur. With all of these unique elements in mind, there are serious ramifications for policy makers to consider when they make decisions.