| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~ 400,000 (c. 2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southern Africa | |

| Languages | |

| Afrikaans, Khoisan languages | |

| Religion | |

| Mainly Christian and African Traditional Religion (San religion) |

Khoisan /ˈkɔɪsɑːn/, or according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography Khoe-Sān (pronounced [kxʰoesaːn]), is a catch-all term for the "non-Bantu" indigenous peoples of Southern Africa, combining the Khoekhoen (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the Sān or Sākhoen (also, in Afrikaans: Boesmans, or in English: Bushmen, after Dutch: Boschjesmens; and Saake in the Nǁng language).

Khoekhoen, specifically, were formerly known as "Hottentots", which was an onomatopoeic term (from Dutch hot-en-tot) referring to the click consonants prevalent in the Khoekhoe languages, as they are in all the languages grouped under Khoesān. Dutchmen in the early Cape settlement would ply Khoekhoen with liquor as an inducement for them to perform a ritual dance. The lyric accompanying the dance sounded, in Dutch ears, like hot-en-tot.

Sān are popularly thought of as foragers in the Kalahari Desert and regions of Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho and South Africa. The word sān is from the Khoekhoe language and simply refers to foragers ("those who pick things up from the ground") who do not own livestock. As such it was used in reference to all hunter-gatherer populations of the Southern African region who Khoekhoe-speaking communities came into contact with, and was largely a term referring to a lifestyle, distinct from a pastoralist or agriculturalist one, not any particular ethnicity. While there are attendant cosmologies and languages associated with this way of life, the term is an economic designator, rather than a cultural or ethnic one.

Khoekhoen is an ethnic designator. It refers to (several) populations which speak closely related languages and which are considered to be the historical pastoralist communities in the South African Cape region, through to Namibia, where Khoekhoe populations of Nama and Damara people are prevalent ethnicities.

These Khoekhoe nations and Sān are grouped under the single term Khoesān as representing the indigenous substrate population of Southern Africa prior to the hypothesised Bantu expansion reaching the area, roughly between 1,500–2,000 years ago.

Many Khoesān peoples are the direct descendants of a very early dispersal of anatomically modern humans to Southern Africa, before 150,000 years ago. Their languages show a vague typological similarity, largely confined to the prevalence of click consonants, and they are not verifiably derived from a common proto-language, but are today split into at least three separate and unrelated language families (Khoe-Kwadi, ǃUi-Taa and Kxʼa). It has been suggested that the Khoekhoeǁaen (Khoekhoe peoples) may represent Late Stone Age arrivals to Southern Africa, possibly displaced by Bantu immigration.

The compound term Khoisan / Khoesān is a modern anthropological convention, in use since the early-to-mid 20th century. Khoisan is a coinage by Leonhard Schulze in the 1920s and popularised by Isaac Schapera. It enters wider usage from the 1960s, based on the proposal of a "Khoisan" language family by Joseph Greenberg.

Khoesān peoples were historically also grouped as Cape Blacks (Afrikaans: Kaap Swartes) or Western Cape Blacks (Afrikaans: Wes-Kaap Swartes) to distinguish them from the Bantu peoples, the other indigenous African population of South Africa.

The term Khoisan (also spelled KhoiSan, Khoi-San, Khoe-San) has also been introduced in South African usage as a self-designation after the end of apartheid, in the late 1990s. Since the 2010s, there has been a "Khoisan activist" movement demanding recognition and land rights from the Bantu majority.

History

Origins

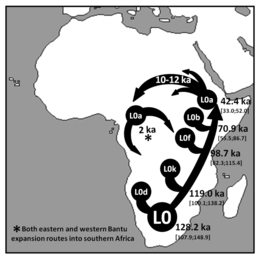

It is suggested that the ancestors of the modern Khoisan expanded to Southern Africa before 150,000 years ago, possibly as early as before 260,000 years ago, so that by the beginning of the MIS 5 "megadrought", 130,000 years ago, there were two ancestral population clusters in Africa, bearers of mt-DNA haplogroup L0 in southern Africa, ancestral to the Khoi-San, and bearers of haplogroup L1-6 in central/eastern Africa, ancestral to everyone else.

Due to their early expansion and separation, the populations ancestral to the Khoisan have been estimated as having represented the "largest human population" during the majority of the anatomically modern human timeline, from their early separation before 150 kya until the recent peopling of Eurasia some 70 kya. They were much more widespread than today, their modern distribution being due to their decimation in the course of the Bantu expansion. They were dispersed throughout much of Southern and South-Eastern Africa. There was also a significant back-migration of bearers of L0 towards eastern Africa between 120 and 75 kya. Rito et al. (2013) speculate that pressure from such back-migration may even have contributed to the dispersal of East African populations out of Africa at about 70 kya. "By ~130 ka two distinct groups of anatomically modern humans co-existed in Africa: broadly, the ancestors of many modern-day Khoe and San populations in the south and a second central/eastern African group that includes the ancestors of most extant worldwide populations. Early modern human dispersals correlate with climate changes, particularly the tropical African "megadroughts" of MIS 5 (marine isotope stage 5, 135–75 ka) which paradoxically may have facilitated expansions in central and eastern Africa, ultimately triggering the dispersal out of Africa of people carrying haplogroup L3 ~60 ka. Two south to east migrations are discernible within haplogroup L0. One, between 120 and 75 ka, represents the first unambiguous long-range modern human dispersal detected by mtDNA and might have allowed the dispersal of several markers of modernity. A second one, within the last 20 ka signalled by L0d, may have been responsible for the spread of southern click-consonant languages to eastern Africa, contrary to the view that these eastern examples constitute relics of an ancient, much wider distribution."

Late Stone Age

The Khoisanid populations ancestral to the Khoisan were spread throughout much of Southern and Eastern Africa throughout the Late Stone Age, after about 75 ka. A further expansion, dated to about 20 ka, has been proposed based on the distribution of the L0d haplogroup. Rosti et al. suggest a connection of this recent expansion with the spread of click consonants to eastern African languages (Hadza language).

The Late Stone Age Sangoan industry occupied southern Africa in areas where annual rainfall is less than a metre (1000 mm; 39.4 in). The contemporary San and Khoi peoples resemble those represented by the ancient Sangoan skeletal remains.

Against the traditional interpretation that finds a common origin for the Khoi and San, other evidence has suggested that the ancestors of the Khoi peoples are relatively recent pre-Bantu agricultural immigrants to Southern Africa, who abandoned agriculture as the climate dried and either joined the San as hunter-gatherers or retained pastoralism.

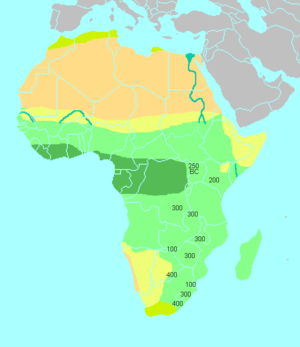

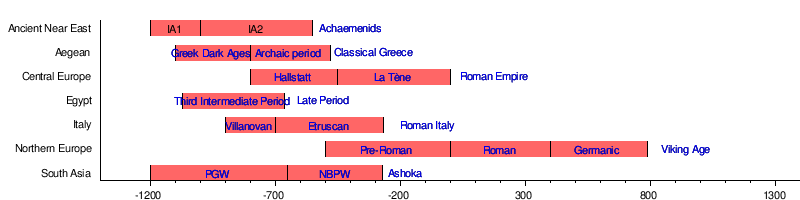

Bantu expansion

Since the arrival of the Bantu expansion starting with the Sandawe people in Southern Africa over 1,500 years ago, linguistic influence is seen in the adoption of click consonants and loan words from Khoisan into the Xhosa and Zulu languages. Bantu-speaking communities would have reached southern Africa from the Congo basin by about the 6th century AD. The advancing Bantu encroached on the Khoikhoi territory, forcing survivors of the indigenous populations to move to more arid areas of the Kalahari.

Their husbandry of sheep, goats and cattle grazing in fertile valleys across the region provided a stable, balanced diet, and allowed the Khoikhoi to live in larger groups in a region previously occupied by the San, who were subsistence hunter-gatherers. Advancing Bantu in the 3rd-6th century AD encroached on the Khoikhoi territory, pushing them into more arid areas. The Bantu people, with advanced agriculture and metalworking technology, outcompeted and intermarried with the Khoisan, becoming the dominant population of South-Eastern Africa before the arrival of the Dutch colonists in 1652.

After the arrival of the Bantu, the Khoisan and their pastoral or hunter-gatherer ways of life remained predominant west of the Fish River in South Africa and in deserts throughout their region, where the drier climate precluded the growth of Bantu crops suited for warmer and wetter climates.

Historical period

The Khoikhoi enter the historical record with their first contact with Portuguese explorers, about 1,000 years after their displacement by the Bantu. Local population dropped after the Khoi were exposed to smallpox from Europeans. The Khoi waged more frequent attacks against Europeans when the Dutch East India Company enclosed traditional grazing land for farms. Khoikhoi social organisation was profoundly damaged and, in the end, destroyed by colonial expansion and land seizure from the late 17th century onwards. As social structures broke down, some Khoikhoi people settled on farms and became bondsmen (bondservants) or farm workers; others were incorporated into existing clan and family groups of the Xhosa people. Georg Schmidt, a Moravian Brother from Herrnhut, Saxony, now Germany, founded Genadendal in 1738, which was the first mission station in southern Africa, among the Khoi people in Baviaanskloof in the Riviersonderend Mountains. Early European settlers sometimes intermarried with Khoikhoi women, resulting in a sizeable mixed-race population now known as the Griqua.

Andries Stockenström facilitated the creation of the "Kat River" Khoi settlement near the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony. The settlements thrived and expanded, and Kat River quickly became a large and successful region of the Cape that subsisted more or less autonomously. The people were predominantly Afrikaans-speaking Gonaqua Khoi, but the settlement also began to attract other Khoi, Xhosa and mixed-race groups of the Cape.

The so-called "Bushman wars" were to a large extent the response of the San after their dispossession.

At the start of the 18th century, the Khoikhoi in the Western Cape lived in a co-operative state with the Dutch. By the end of the century the majority of the Khoisan operated as 'wage labourers', not that dissimilar to slaves. Geographically, the further away the labourer was from Cape Town, the more difficult it became to transport agricultural produce to the markets. The issuing of grazing licences north of the Berg River in what was then the Tulbagh Basin propelled colonial expansion in the area. This system of land relocation led to the Khoijhou losing their land and livestock as well as dramatic change in the social, economic and political development.

After the defeat of the Xhosa rebellion in 1853, the new Cape Government endeavoured to grant the Khoi political rights to avert future racial discontent. The government enacted the Cape franchise in 1853, which decreed that all male citizens meeting a low property test, regardless of colour, had the right to vote and to seek election in Parliament. This non-racial principle was later abolished by the apartheid Government.

In the Herero and Namaqua genocide in German South-West Africa, over 10,000 Nama are estimated to have been killed during 1904–1907.

The San of the Kalahari were described in Specimens of Bushman Folklore by Wilhelm H. I. Bleek and Lucy C. Lloyd (1911). They were brought to the globalised world's attention in the 1950s by South African author Laurens van der Post in a six-part television documentary. The Ancestral land conflict in Botswana concerns the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), established in 1961 for wildlife, while the San were permitted to continue their hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In the 1990s, the government of Botswana began a policy of "relocating" CKGR residents outside the reserve. In 2002, the government cut off all services to CKGR residents. A legal battle began, and in 2006 the High Court of Botswana ruled that the residents had been forcibly and unconstitutionally removed. The policy of relocation continued, however, and in 2012 the San people (Basarwa) appealed to the United Nations to force the government to recognise their land and resource rights.

Following the end of Apartheid in 1994, the term "Khoisan" has gradually come to be used as a self-designation by South African Khoikhoi as representing the "first nations" of South Africa vis-a-vis the ruling Bantu majority. A conference on "Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage" was organised by the University of the Western Cape in 1997. and "Khoisan activism" has been reported in the South African media beginning in 2015.

The South African government allowed Khoisan families (up until 1998) to pursue land claims which existed prior to 1913. The South African Deputy Chief Land Claims Commissioner, Thami Mdontswa, has said that constitutional reform would be required to enable Khoisan people to pursue further claims to land from which their direct ancestors were removed prior to 9 June 1913.

"Bosjemans frying locusts", aquatint by Samuel Daniell (1805).

Discoveries

In 2019, scientists from the University of the Free State discovered 8,000-year-old carvings made by the Khoisan people. The carvings depicted a hippopotamus, horse, and antelope in the 'Rain Snake' Dyke of the Vredefort structure, which may have spiritual significance regarding the rain-making mythology of the Khoisan.

Languages

The "Khoisan languages" were proposed as a linguistic phylum by Joseph Greenberg in 1955. Their genetic relationship was questioned later in the 20th century, and the term now serves mostly as a convenience term without implying genetic unity, much like "Papuan" and "Australian" are. Their most notable uniting feature is their click consonants.

They are categorized in two families, and a number of possible language isolates.

The Kxʼa family was proposed in 2010, combining the ǂʼAmkoe (ǂHoan) language with the ǃKung (Juu) dialect cluster. ǃKung includes about a dozen dialects, with no clear-cut delineation between them. Sands et al. (2010) propose a division into four clusters:

- Northern ǃKung (Sekele), spoken in Angola around the Cunene, Cubango, Cuito, and Cuando rivers (but with many refugees now in Namibia),

- North-Central ǃKung (Ekoka), spoken in Namibia between the Ovambo River and the Angolan border,

- Central ǃKung, spoken around Grootfontein, Namibia, west of the central Omatako River and south of the Ovambo River

- Southeastern ǃKung (Juǀ'hoan), spoken in Botswana east of the Okavango Delta, and northeast Namibia from near Windhoek to Rundu, Gobabis, and the Caprivi Strip.

The Khoi (Khoe) family is divided into a Khoikhoi (Khoekhoe and Khoemana dialects) and a Kalahari (Tshu–Khwe) branch. The Kalahari branch of Khoe includes Shua and Tsoa (with dialects), and Kxoe, Naro, Gǁana and ǂHaba (with dialects). Khoe also has been tentatively aligned with Kwadi ("Kwadi–Khoe"), and more speculatively with the Sandawe language of Tanzania ("Khoe–Sandawe"). The Hadza language of Tanzania has been associated with the Khoisan group due to the presence of click consonants.

Physical characteristics and genetics

Charles Darwin wrote about the Khoisan and sexual selection in The Descent of Man in 1882, commenting that their steatopygia evolved through sexual selection in human evolution, and that "the posterior part of the body projects in a most wonderful manner".

In the 1990s, genomic studies of the world's peoples found that the Y chromosome of San men share certain patterns of polymorphisms that are distinct from those of all other populations. Because the Y chromosome is highly conserved between generations, this type of DNA test is used to determine when different subgroups separated from one another, and hence their last common ancestry. The authors of these studies suggested that the San may have been one of the first populations to differentiate from the most recent common paternal ancestor of all extant humans.

Various Y-chromosome studies since confirmed that the Khoisan carry some of the most divergent (oldest) Y-chromosome haplogroups. These haplogroups are specific sub-groups of haplogroups A and B, the two earliest branches on the human Y-chromosome tree.

Similar to findings from Y-chromosome studies, mitochondrial DNA studies also showed evidence that the Khoisan people carry high frequencies of the earliest haplogroup branches in the human mitochondrial DNA tree. The most divergent (oldest) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African Khoi and San groups. The distinctiveness of the Khoisan in both matrilineal and patrilineal groupings is a further indicator that they represent a population historically distinct from other Africans.

Research and academic centre

On 21 September 2020 the University of Cape Town launched its new Khoi and San Centre, with an undergraduate degree programme planned to be rolled out in coming years. The centre will support and consolidate this collaborative work on research commissions on language (including Khoekhoegowab), sacred human remains, land and gender. Many descendants of Khoisan people still live on the Cape Flats.