Defamation of religion is an issue that was repeatedly addressed by some member states of the United Nations (UN) from 1999 until 2010. Several non-binding resolutions were voted on and accepted by the UN condemning "defamation of religion". The motions, sponsored on behalf of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC), now known as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, sought to prohibit expression that would "fuel discrimination, extremism and misperception leading to polarization and fragmentation with dangerous unintended and unforeseen consequences". Religious groups, human rights activists, free-speech activists, and several countries in the West condemned the resolutions arguing they amounted to an international blasphemy law. Critics of the resolutions, including human rights groups, argued that they were used to politically strengthen domestic anti-blasphemy and religious defamation laws, which are used to imprison journalists, students and other peaceful political dissidents.

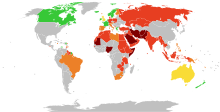

From 2001 to 2010 there was a split of opinion, with the Islamic bloc and much of the developing world supporting the defamation of religion resolutions, and mostly Western democracies opposing them. Support waned toward the end of the period, due to increased opposition from the West, along with lobbying by religious, free-speech, and human rights advocacy groups. Some countries in Africa, the Pacific, and Latin America switched from supporting to abstaining, or from abstaining to opposing. The final "defamation of religions" resolution in 2010, which also condemned "the ban on the construction of minarets of mosques" four months after a Swiss referendum introduced such a ban, passed with 20 supporting, 17 opposing, and 8 abstaining.

In 2011, with falling support for the defamation of religion approach, the OIC changed their approach and introduced a new resolution on "Combating intolerance, negative stereotyping and stigmatization of, and discrimination, incitement to violence and violence against, persons based on religion or belief"; it received unanimous support.

The UN Human Rights Committee followed this in July 2011 with the adoption of General Comment 34 on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) 1976 that binds signatory countries. Concerning freedoms of opinion and expression, General Comment 34 made it clear that "Prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible with the Covenant". General Comment 34 makes it clear that countries with blasphemy laws in any form that have signed the ICCPR are in breach of their obligations under the ICCPR.

United Nations resolutions

Defamation of religion resolutions were the subject of debate by the UN from 1999 until 2010. In 2011, members of the UN Human Rights Council found compromise and replaced the "defamation of religions" resolution with Resolution 16/18, which sought to protect people rather than religions and called upon states to take concrete steps to protect religious freedom, prohibit discrimination and hate crimes, and counter offensive expression through dialogue, education, and public debate rather than the criminalization of speech. Resolution 16/18 was supported by both OIC member countries and Western countries, including the United States.

1999

In April 1999, at the urging of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), Pakistan brought before the United Nations Commission on Human Rights a resolution entitled "Defamation of Islam". The purpose of the resolution was to have the Commission stand up against what the OIC claimed was a campaign to defame Islam. Some members of the Commission proposed that the resolution be changed to embrace all religions. The Commission accepted the proposal, and changed the title of the resolution to "Defamation of Religions". The resolution urged "all States, within their national legal framework, in conformity with international human rights instruments to take all appropriate measures to combat hatred, discrimination, intolerance and acts of violence, intimidation and coercion motivated by religious intolerance, including attacks on religious places, and to encourage understanding, tolerance and respect in matters relating to freedom of religion or belief". The Commission adopted the resolution without a vote.

2000 to 2005

In 2000, the CHR adopted a similar resolution without a vote. In 2001, a vote on a resolution entitled "Combating defamation of religions as a means to promote human rights, social harmony and religious and cultural diversity" received 28 votes in favour, 15 against, and 9 abstentions. In 2002, a vote on a resolution entitled "Combating defamation of religion" received 30 votes in favour, 15 against, and 8 abstentions. In 2003, 2004, and 2005, by similar votes, the CHR approved resolutions entitled "Combating defamation of religions".

In 2005, Yemen introduced a resolution entitled "Combating Defamation of Religions" in the General Assembly (60th Session). 101 states voted in favour of the resolution, 53 voted against, and 20 abstained.

2006

In March 2006, the CHR became the UNHRC. The UNHRC approved a resolution entitled "Combating Defamation of Religions", and submitted it to the General Assembly. In the General Assembly, 111 member states voted in favour of the resolution, 54 voted against, and 18 abstained. Russia and China, permanent members of the UN Security Councils, voted for the Resolution.

2007

On 30 March 2007, the UNHRC adopted a resolution entitled "Combating Defamation of Religions". The resolution called upon the High Commissioner for Human Rights to report on the activities of her office with regard to combating defamation of religions.

On 30 March 2007, the UNHRC adopted a resolution entitled "Elimination of all forms of intolerance and of discrimination based on religion or belief". The resolution called upon the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief to report on this issue for the Human Rights Council at its sixth session.

In August 2007, the Special Rapporteur, Doudou Diène, reported to the General Assembly "on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance on the manifestations of defamation of religions and in particular on the serious implications of Islamophobia on the enjoyment of all rights". Among other recommendations, the Special Rapporteur recommended that the Member States promote dialogue between cultures, civilizations, and religions taking into consideration:

(a) The need to provide equal treatment to the combat of all forms of defamation of religions, thus avoiding hierarchization of forms of discrimination, even though their intensity may vary according to history, geography and culture;

(b) The historical and cultural depth of all forms of defamation of religions, and therefore the need to complement legal strategies with an intellectual and ethical strategy relating to the processes, mechanisms and representations which constitute those manifestations over time; ...

(e) The need to pay particular attention and vigilance to maintain a careful balance between secularism and the respect of freedom of religion. A growing anti-religious culture and rhetoric is a central source of defamation of all religions and discrimination against their believers and practitioners. In this context governments should pay a particular attention to guaranteeing and protecting the places of worship and culture of all religions.

On 4 September 2007, the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported to the UNHRC that "Enhanced cooperation and stronger political will by Member States are essential for combating defamation of religions".

On 18 December 2007, the General Assembly voted on another resolution entitled "Combating Defamation of Religions". 108 states voted in favour of the resolution; 51 voted against it; and 25 abstained. The resolution required the Secretary General to report to the sixty-third session of the General Assembly on the implementation of the resolution, and to have regard for "the possible correlation between defamation of religions and the upsurge in incitement, intolerance and hatred in many parts of the world".

2008

On 27 March 2008, the UNHRC passed another resolution about the defamation of religion. The resolution :

10. Emphasizes that respect of religions and their protection from contempt is an essential element conducive for the exercise by all of the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion;

11. Urges all States to ensure that all public officials, including members of law enforcement bodies, the military, civil servants and educators, in the course of their official duties, respect all religions and beliefs and do not discriminate against persons on the grounds of their religion or belief, and that all necessary and appropriate education or training is provided;

12. Emphasizes that, as stipulated in international human rights law, everyone has the right to freedom of expression, and that the exercise of this right carries with it special duties and responsibilities, and may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but only those provided by law and necessary for the respect of the rights or reputations of others, or for the protection of national security or of public order, or of public health or morals;

13. Reaffirms that general comment No. 15 of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, in which the Committee stipulates that the prohibition of the dissemination of all ideas based upon racial superiority or hatred is compatible with the freedom of opinion and expression, is equally applicable to the question of incitement to religious hatred;

14. Deplores the use of printed, audio-visual and electronic media, including the Internet, and of any other means to incite acts of violence, xenophobia or related intolerance and discrimination towards Islam or any religion;

15. Invites the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance to continue to report on all manifestations of defamation of religions, and in particular on the serious implications of Islamophobia, on the enjoyment of all rights to the Council at its ninth session;

16. Requests the High Commissioner for Human Rights to report on the implementation of the present resolution and to submit a study compiling relevant existing legislations and jurisprudence concerning defamation of and contempt for religions to the Council at its ninth session.

21 members were in favour of the resolution; 10 were opposed; 14 abstained.

The High Commissioner presented her report about defamation of, and contempt for, religions on 5 September 2008. She proposed the holding of a consultation with experts from 2 to 3 October 2008 in Geneva about the permissible limitations to freedom of expression in accordance with international human rights law. In another report, dated 12 September 2008, the High Commissioner noted that different countries have different notions of what "defamation of religion" means.

Githu Muigai, Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, addressed the UNHRC on 19 September 2008. He delivered the report prepared by Doudou Diène. The report called on Member States to shift the present discussion in international fora from the idea of "defamation of religions" to the legal concept: "incitement to national, racial or religious hatred," which is grounded on international legal instruments.

On 24 November 2008, during the Sixty-third Session, the General Assembly's Third Committee (Social, Humanitarian & Cultural) approved a resolution entitled "Combating defamation of religions". The resolution requests "the Secretary-General to submit a report on the implementation of the present resolution, including on the possible correlation between defamation of religions and the upsurge in incitement, intolerance and hatred in many parts of the world, to the General Assembly at its sixty-fourth session". 85 states voted in favour of the resolution; 50 states voted against the resolution; 42 states abstained.

2009

In February 2009, Zamir Akram, permanent representative of Pakistan to the United Nations Office at Geneva, in a meeting of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, commented on the "defamation of religion". He said "there was an impression that Pakistan was trying to put in place an international anti-defamation provision in the context of the Durban Review Conference". Akram said the impression "was totally incorrect". Akram's delegation said:

... defamation of religions could and had led to violence... . The end result was the creation of a kind of Islamophobia in which Muslims were typecast as terrorists. That did not mean that they opposed freedom of expression; it merely meant that there was a level at which such expression led to incitement. An example was the propaganda campaign that had been led by the Nazis in the Second World War against the Jews which had led to The Holocaust."

In advance of 26 March 2009, more than 200 civil society organizations from 46 countries, including Muslim, Christian, Jewish, secular, Humanist and atheist groups, urged the UNHRC by a joint petition to reject any resolution against the defamation of religion.

On 26 March 2009, the UNHRC passed a resolution, proposed by Pakistan, which condemned the "defamation of religion" as a human rights violation by a vote of 23–11, with 13 abstentions. The resolution:

17. Expresses its appreciation to the High Commissioner for holding a seminar on freedom of expression and advocacy of religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence, in October 2008, and requests her to continue to build on this initiative, with a view to contributing concretely to the prevention and elimination of all such forms of incitement and the consequences of negative stereotyping of religions or beliefs, and their adherents, on the human rights of those individuals and their communities;

18. Requests the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance to report on all manifestations of defamation of religions, and in particular on the serious implications of Islamophobia, on the enjoyment of all rights by their followers, to the Council at its twelfth session;

19. Requests the High Commissioner for Human Rights to report to the Council at its twelfth session on the implementation of the present resolution, including on the possible correlation between defamation of religions and the upsurge in incitement, intolerance and hatred in many parts of the world.

Supporters of the resolution argued that the resolution is necessary to prevent the defamation of Islam while opponents argued that such a resolution was an attempt to bring to the international body the anti-defamation laws prevalent in some Muslim countries.

On 1 July 2009, Githu Muigai, Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, submitted to the UNHRC the report requested by it on 26 March 2009. The report "reiterates the recommendation of his predecessor to encourage a shift away from the sociological concept of the defamation of religions towards the legal norm of non-incitement to national, racial or religious hatred".

On 31 July 2009, the Secretary General submitted to the General Assembly the report that it requested in November 2008. The Secretary General noted, "The Special Rapporteurs called for anchoring the debate in the existing international legal framework provided by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – more specifically its articles 19 and 20." The Secretary General concluded, "In order to tackle the root causes of intolerance, a much broader set of policy measures needs to be addressed covering the areas of intercultural dialogue as well as education for tolerance and diversity."

On 30 September 2009, at the UNHRC's twelfth session, the United States and Egypt introduced a resolution which condemned inter alia "racial and religious stereotyping". The European Union's representative, Jean-Baptiste Mattei (France), said the European Union "rejected and would continue to reject the concept of defamation of religions". He said, "Human rights laws did not and should not protect belief systems." The OIC's representative on the UNHRC, Zamir Akram (Pakistan), said, "Negative stereotyping or defamation of religions was a modern expression of religious hatred and xenophobia." Carlos Portales (Chile) observed, "The concept of the defamation of religion took them in an area that could lead to the actual prohibition of opinions." The UNHRC adopted the resolution without a vote.

In Geneva, from 19 to 30 October 2009, the Ad Hoc Committee of the Human Rights Council on the Elaboration of Complementary Standards met to update the measures for combating racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance that the Durban I conference had formulated. The committee achieved little because of conflict over a variety of issues including "defamation of religion". The United States said that defamation of religion is "a fundamentally flawed concept". Sweden, for the European Union, argued that international human rights law protects individuals, not institutions or religions. France insisted that the UN must not afford legal protection to systems of belief. Syria criticized the "typical and expected Western silence" on "acts of religious discrimination". Syria said "in real terms defamation means targeting Muslims".

Zamir Akram (Pakistan) wrote to the Ad Hoc Committee on 29 October 2009 to explain why the OIC would not abandon the idea of defamation of religion. Akram's letter states:

The OIC is concerned by the instrumentalization of religions through distortion or ridicule aimed at demeaning and provoking their followers to violence as well as at promoting contempt towards religious communities in order to de-humanize their constituent members with purpose of justifying advocacy of racial and religious hatred and violence against these individuals.

The letter says defamation of religion has been "wrongly linked with malafide intentions to its perceived clash with" the freedom of opinion and expression. The letter declares:

All religions are sacred and merit equal respect and protection. Double standards, including institutional preferential treatment for one religion or group of people must be avoided. The OIC demands similar sanctity for all religions, their religious personalities, symbols and followers. Tolerance and understanding cannot merely be addressed through open debate and inter-cultural dialogue as defamation trends are spreading to the grass root levels. These growing tendencies need to be checked by introducing a single universal international human rights framework.

In New York, on 29 October 2009, the UN's Third Committee (Social, Humanitarian & Cultural) approved a draft resolution entitled "Combating defamation of religions" by a vote which had 81 for, 55 against, and 43 abstaining.

On 18 December 2009, the General Assembly approved a resolution deploring the defamation of religions by a vote of 80 nations in favour and 61 against with 42 abstentions.

2010

In March 2010, Pakistan again brought forward a resolution entitled "Combating defamation of religions" on behalf of the OIC.

The resolution received much criticism. French ambassador Jean-Baptiste Mattei, speaking on behalf of the European Union, argued that the "concept of defamation should not fall under the remit of human rights because it conflicted with the right to freedom of expression". Eileen Donahoe, the US ambassador, also rejected the resolution. She said, "We cannot agree that prohibiting speech is the way to promote tolerance, because we continue to see the 'defamation of religions' concept used to justify censorship, criminalisation, and in some cases violent assaults and deaths of political, racial, and religious minorities around the world."

The UNHRC passed the resolution on 25 March 2010 with 20 members voting in favour; 17 members voting against; 8 abstaining; and 2 absent.

2011

In early 2011, with declining support for the defamation of religion approach and at the time of the Arab Spring, which was in part due to a lack of freedom of speech, political freedoms, poor living conditions, corruption, and rising food prices, there was a real possibility that another resolution on the defamation of religion would be defeated. The OIC shifted position and opted to pursue an approach that would gain the support from both OIC and Western countries. On 24 March 2011, the UN Human Rights Council in a very significant move shifted from protecting beliefs to the protection of believers with the unanimous adoption without a vote of Resolution 16/18 introduced by Pakistan.

Among its many specific points, Resolution 16/18 on Combating intolerance, negative stereotyping and stigmatization of, and discrimination, incitement to violence, and violence against persons based on religion or belief, highlights barriers to religiously tolerant societies and provides recommendations on how these barriers can be overcome. The resolution calls upon all member states to foster religious freedom and pluralism, to ensure religious minorities are properly represented, and to consider adopting measures to criminalize incitement to imminent violence based on religion or belief. Other recommendations include creating government programs to promote inter-religious tolerance and dialogue, training government employees to be sensitive toward religious sensitivities, and engaging in outreach initiatives.

At a meeting on 15 July 2011, hosted by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation at the OIC/IRCICA premises in the historic Yildiz Palace in Istanbul and co-chaired by the OIC Secretary-General Prof. Ekmeleddin Ihsanogl, U.S. Secretary of State Mrs. Hillary Rodham Clinton and the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, together with foreign ministers and officials from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Egypt, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Senegal, Sudan, United Kingdom, the Vatican (Holy See), UN OHCHR, Arab League, African Union, gave a united impetus to the implementation of UN Human Rights Council Resolution 16/18 with the release of a Joint Statement. The text includes the following:

- "They called upon all relevant stakeholders throughout the world to take seriously the call for action set forth in Resolution 16/18, which contributes to strengthening the foundations of tolerance and respect for religious diversity as well as enhancing the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms around the world.

- Participants, resolved to go beyond mere rhetoric, and to reaffirm their commitment to freedom of religion or belief and freedom of expression by urging States to take effective measures, as set forth in Resolution 16/18, consistent with their obligations under international human rights law, to address and combat intolerance, discrimination, and violence based on religion or belief. The co-chairs of the meeting committed to working together with other interested countries and actors on follow up and implementation of Resolution 16/18 and to conduct further events and activities to discuss and assess implementation of the resolution."

In July, 2011, the UN Human Rights Committee adopted a 52-paragraph statement, General Comment 34 on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) 1976, concerning freedoms of opinion and expression. Paragraph 48 states:

- Prohibitions of displays of lack of respect for a religion or other belief system, including blasphemy laws, are incompatible with the Covenant, except in the specific circumstances envisaged in article 20, paragraph 2, of the Covenant. Such prohibitions must also comply with the strict requirements of article 19, paragraph 3, as well as such articles as 2, 5, 17, 18 and 26. Thus, for instance, it would be impermissible for any such laws to discriminate in favor of or against one or certain religions or belief systems, or their adherents over another, or religious believers over non-believers. Nor would it be permissible for such prohibitions to be used to prevent or punish criticism of religious leaders or commentary on religious doctrine and tenets of faith.

Article 20, paragraph 2 of the Covenant states: Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.

The ICCPR binds all signatory countries. Consequently, countries with blasphemy laws in any form that have signed the ICCPR are in breach of their obligations under the ICCPR.

On 19 December 2011, the UN General Assembly endorsed Human Rights Council Resolution 16/18 with the adoption of Resolution 66/167. The resolution was sponsored by the OIC after consultations with the United States and the European Union and co-sponsored by Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, Uruguay, Thailand and the Dominican Republic. With longer preambular statements, Resolution 66/167 repeats the language and substantive paragraphs of Resolution 16/18.

2012

At the nineteenth session of the Human Rights Council, on 22 March 2012, the Human Rights Council reaffirmed Resolution 16/18 with the unanimous adoption of Resolution 19/8. The General Assembly followed on 20 December 2012 with the adoption of Resolution 67/178.