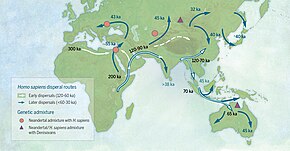

Following the peopling of Africa some 130,000 years ago, and the recent Out-of-Africa expansion some 70,000 to 50,000 years ago, some sub-populations of Homo sapiens have been geographically isolated for tens of thousands of years prior to the early modern Age of Discovery. Combined with archaic admixture, this has resulted in relatively significant genetic variation. Selection pressures were especially severe for populations affected by the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) in Eurasia, and for sedentary farming populations since the Neolithic, or New Stone Age.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP, pronounced 'snip'), or mutations of a single genetic code "letter" in an allele that spread across a population, in functional parts of the genome can potentially modify virtually any conceivable trait, from height and eye color to susceptibility to diabetes and schizophrenia. Approximately 2% of the human genome codes for proteins and a slightly larger fraction is involved in gene regulation. But most of the rest of the genome has no known function. If the environment remains stable, the beneficial mutations will spread throughout the local population over many generations until it becomes a dominant trait. An extremely beneficial allele could become ubiquitous in a population in as little as a few centuries whereas those that are less advantageous typically take millennia.

Human traits that emerged recently include the ability to free-dive for long periods of time, adaptations for living in high altitudes where oxygen concentrations are low, resistance to contagious diseases (such as malaria), light skin, blue eyes, lactase persistence (or the ability to digest milk after weaning), lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels, retention of the median artery, reduced prevalence of Alzheimer's disease, lower susceptibility to diabetes, genetic longevity, shrinking brain sizes, and changes in the timing of menarche and menopause.

Archaic admixture

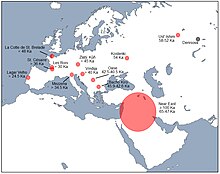

Genetic evidence suggests that a species dubbed Homo heidelbergensis is the last common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo sapiens. This common ancestor lived between 600,000 and 750,000 years ago, likely in either Europe or Africa. Members of this species migrated throughout Europe, the Middle East, and Africa and became the Neanderthals in Western Asia and Europe while another group moved further east and evolved into the Denisovans, named after the Denisova Cave in Russia where the first known fossils of them were discovered. In Africa, members of this group eventually became anatomically modern humans. Migrations and geographical isolation notwithstanding, the three descendant groups of Homo heidelbergensis later met and interbred.

Archaeological research suggests that as prehistoric humans swept across Europe 45,000 years ago, Neanderthals went extinct. Even so, there is evidence of interbreeding between the two groups as humans expanded their presence in the continent. While prehistoric humans carried 3–6% Neanderthal DNA, modern humans have only about 2%. This seems to suggest selection against Neanderthal-derived traits. For example, the neighborhood of the gene FOXP2, affecting speech and language, shows no signs of Neanderthal inheritance whatsoever.

Introgression of genetic variants acquired by Neanderthal admixture has different distributions in Europeans and East Asians, pointing to differences in selective pressures. Though East Asians inherit more Neanderthal DNA than Europeans, East Asians, South Asians, Australo-Melanesians, Native Americans, and Europeans all share Neanderthal DNA, so hybridization likely occurred between Neanderthals and their common ancestors coming out of Africa. Their differences also suggest separate hybridization events for the ancestors of East Asians and other Eurasians.

Following the genome sequencing of three Vindija Neanderthals, a draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome was published and revealed that Neanderthals shared more alleles with Eurasian populations—such as French, Han Chinese, and Papua New Guinean—than with sub-Saharan African populations, such as Yoruba and San. According to the authors of the study, the observed excess of genetic similarity is best explained by recent gene flow from Neanderthals to modern humans after the migration out of Africa. But gene flow did not go one way. The fact that some of the ancestors of modern humans in Europe migrated back into Africa means that modern Africans also carry some genetic materials from Neanderthals. In particular, Africans share 7.2% Neanderthal DNA with Europeans but only 2% with East Asians.

Some climatic adaptations, such as high-altitude adaptation in humans, are thought to have been acquired by archaic admixture. An ethnic group known as the Sherpas from Nepal is believed to have inherited an allele called EPAS1, which allows them to breathe easily at high altitudes, from the Denisovans. A 2014 study reported that Neanderthal-derived variants found in East Asian populations showed clustering in functional groups related to immune and haematopoietic pathways, while European populations showed clustering in functional groups related to the lipid catabolic process. A 2017 study found correlation of Neanderthal admixture in modern European populations with traits such as skin tone, hair color, height, sleeping patterns, mood and smoking addiction. A 2020 study of Africans unveiled Neanderthal haplotypes, or alleles that tend to be inherited together, linked to immunity and ultraviolet sensitivity.

The gene microcephalin (MCPH1), involved in the development of the brain, likely originated from a Homo lineage separate from that of anatomically modern humans, but was introduced to them around 37,000 years ago, and has become much more common ever since, reaching around 70% of the human population at present. Neanderthals were suggested as one possible origin of this gene. But later studies did not find this gene in the Neanderthal genome nor has it been found to be associated with cognitive ability in modern people.

The promotion of beneficial traits acquired from admixture is known as adaptive introgression.

A study concluded only 1.5–7% of "regions" of the modern human genome to be specific to modern humans. These regions have neither been altered by archaic hominin DNA due to admixture (only a small portion of archaic DNA is inherited per individual but a large portion is inherited across populations overall) nor are shared with Neanderthals or Denisovans in any of the genomes of the used datasets. They also found two bursts of changes specific to modern human genomes which involve genes related to brain development and function.

Upper Paleolithic, or the Late Stone Age (50,000 to 12,000 years ago)

Victorian naturalist Charles Darwin was the first to propose the out-of-Africa hypothesis for the peopling of the world, but the story of prehistoric human migration is now understood to be much more complex thanks to twenty-first-century advances in genomic sequencing. There were multiple waves of dispersal of anatomically modern humans out of Africa, with the most recent one dating back to 70,000 to 50,000 years ago. Earlier waves of human migrants might have gone extinct or returned to Africa. Moreover, a combination of gene flow from Eurasia back into Africa and higher rates of genetic drift among East Asians compared to Europeans led these human populations to diverge from one another at different times.

Around 65,000 to 50,000 years ago, a variety of new technologies, such as projectile weapons, fish hooks, porcelain, and sewing needles, made their appearance. Bird-bone flutes were invented 30,000 to 35,000 years ago, indicating the arrival of music. Artistic creativity also flowered, as can be seen with Venus figurines and cave paintings. Cave paintings of not just actual animals but also imaginary creatures that could reliably be attributed to Homo sapiens have been found in different parts of the world. Radioactive dating suggests that the oldest of the ones that have been found, as of 2019, are 44,000 years old. For researchers, these artworks and inventions represent a milestone in the evolution of human intelligence, the roots of story-telling, paving the way for spirituality and religion. Experts believe this sudden "great leap forward"—as anthropologist Jared Diamond calls it—was due to climate change. Around 60,000 years ago, during the middle of an ice age, it was extremely cold in the far north, but ice sheets sucked up much of the moisture in Africa, making the continent even drier and droughts much more common. The result was a genetic bottleneck, pushing Homo sapiens to the brink of extinction, and a mass exodus from Africa. Nevertheless, it remains uncertain (as of 2003) whether or not this was due to some favorable genetic mutations, for example in the FOXP2 gene, linked to language and speech. A combination of archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that humans migrated along Southern Asia and down to Australia 50,000 years ago, to the Middle East and then to Europe 35,000 years ago, and finally to the Americas via the Siberian Arctic 15,000 years ago.

DNA analyses conducted since 2007 revealed the acceleration of evolution with regards to defenses against disease, skin color, nose shapes, hair color and type, and body shape since about 40,000 years ago, continuing a trend of active selection since humans emigrated from Africa 100,000 years ago. Humans living in colder climates tend to be more heavily built compared to those in warmer climates because having a smaller surface area compared to volume makes it easier to retain heat. People from warmer climates tend to have thicker lips, which have large surface areas, enabling them to keep cool. With regards to nose shapes, humans residing in hot and dry places tend to have narrow and protruding noses in order to reduce loss of moisture. Humans living in hot and humid places tend to have flat and broad noses that moisturize inhaled air and retain moisture from exhaled air. Humans dwelling in cold and dry places tend to have small, narrow, and long noses in order to warm and moisturize inhaled air. As for hair types, humans from regions with colder climates tend to have straight hair so that the head and neck are kept warm. Straight hair also allows cool moisture to quickly fall off the head. On the other hand, tight and curly hair increases the exposed areas of the scalp, easing the evaporation of sweat and allowing heat to be radiated away while keeping itself off the neck and shoulders. Epicanthic eye folds are believed to be an adaptation protecting the eye from overexposure to ultraviolet radiation, and is presumed to be a particular trait in archaic humans from eastern and southeast Asia. A cold-adaptive explanation for the epicanthic fold is today seen as outdated by some, as epicanthic folds appear in some African populations. Dr. Frank Poirier, a physical anthropologist at Ohio State University, concluded that the epicanthic fold in fact may be an adaptation for tropical regions, and was already part of the natural diversity found among early modern humans.

Physiological or phenotypical changes have been traced to Upper Paleolithic mutations, such as the East Asian variant of the EDAR gene, dated to about 35,000 years ago in Southern or Central China. Traits affected by the mutation are sweat glands, teeth, hair thickness and breast tissue. While Africans and Europeans carry the ancestral version of the gene, most East Asians have the mutated version. By testing the gene on mice, Yana G. Kamberov and Pardis C. Sabeti and their colleagues at the Broad Institute found that the mutated version brings thicker hair shafts, more sweat glands, and less breast tissue. East Asian women are known for having comparatively small breasts and East Asians in general tend to have thick hair. The research team calculated that this gene originated in Southern China, which was warm and humid, meaning having more sweat glands would be advantageous to the hunter-gatherers who lived there. A subsequent study from 2021, based on ancient DNA samples, has suggested that the derived variant became dominant among "Ancient Northern East Asians" shortly after the Last Glacial Maximum in Northeast Asia, around 19,000 years ago. Ancient remains from Northern East Asia, such as the Tianyuan Man (40,000 years old) and the AR33K (33,000 years old) specimen lacked the derived EDAR allele, while ancient East Asian remains after the LGM carry the derived EDAR allele. The frequency of 370A is most highly elevated in North Asian and East Asian populations.

The most recent Ice Age peaked in intensity between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago and ended about 12,000 years ago. As the glaciers that once covered Scandinavia all the way down to Northern France retreated, humans began returning to Northern Europe from the Southwest, modern-day Spain. But about 14,000 years ago, humans from Southeastern Europe, especially Greece and Turkey, began migrating to the rest of the continent, displacing the first group of humans. Analysis of genomic data revealed that all Europeans since 37,000 years ago have descended from a single founding population that survived the Ice Age, with specimens found in various parts of the continent, such as Belgium. Although this human population was displaced 33,000 years ago, a genetically related group began spreading across Europe 19,000 years ago. Recent divergence of Eurasian lineages was sped up significantly during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), the Mesolithic and the Neolithic, due to increased selection pressures and founder effects associated with migration. Alleles predictive of light skin have been found in Neanderthals, but the alleles for light skin in Europeans and East Asians, KITLG and ASIP, are (as of 2012) thought to have not been acquired by archaic admixture but recent mutations since the LGM. Hair, eye, and skin pigmentation phenotypes associated with humans of European descent emerged during the LGM, from about 19,000 years ago. The associated TYRP1 SLC24A5 and SLC45A2 alleles emerge around 19,000 years ago, still during the LGM, most likely in the Caucasus. Within the last 20,000 years or so, lighter skin has evolved in East Asia, Europe, North America and Southern Africa. In general, people living in higher latitudes tend to have lighter skin. The HERC2 variation for blue eyes first appears around 14,000 years ago in Italy and the Caucasus.

Inuit adaptation to high-fat diet and cold climate has been traced to a mutation dated the Last Glacial Maximum (20,000 years ago). Average cranial capacity among modern male human populations varies in the range of 1,200 to 1,450 cm3. Larger cranial volumes are associated with cooler climatic regions, with the largest averages being found in populations of Siberia and the Arctic. Humans living in Northern Asia and the Arctic have evolved the ability to develop thick layers of fat on their faces to keep warm. Moreover, the Inuit tend to have flat and broad faces, an adaptation that reduces the likelihood of frostbites. Both Neanderthal and Cro-Magnons had somewhat larger cranial volumes on average than modern Europeans, suggesting the relaxation of selection pressures for larger brain volume after the end of the LGM.

Australian Aboriginals living in the Central Desert, where the temperature can drop below freezing at night, have evolved the ability to reduce their core temperatures without shivering.

Holocene (12,000 years ago to present)

Neolithic or New Stone Age

Impacts of agriculture

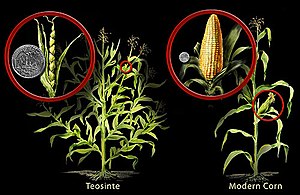

The advent of agriculture has played a key role in the evolutionary history of humanity. Early farming communities benefited from new and comparatively stable sources of food, but were also exposed to new and initially devastating diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, and smallpox. Eventually, genetic resistance to such diseases evolved and humans living today are descendants of those who survived the agricultural revolution and reproduced. The pioneers of agriculture faced tooth cavities, protein deficiency and general malnutrition, resulting in shorter statures. Diseases are one of the strongest forces of evolution acting on Homo sapiens. As this species migrated throughout Africa and began colonizing new lands outside the continent around 100,000 years ago, they came into contact with and helped spread a variety of pathogens with deadly consequences. In addition, the dawn of agriculture led to the rise of major disease outbreaks. Malaria is the oldest known of human contagions, traced to West Africa around 100,000 years ago, before humans began migrating out of the continent. Malarial infections surged around 10,000 years ago, raising the selective pressures upon the affected populations, leading to the evolution of resistance.

Examples for adaptations related to agriculture and animal domestication include East Asian types of ADH1B associated with rice domestication, and lactase persistence.

Migrations

As Europeans and East Asians migrated out of Africa, those groups were maladapted and came under stronger selective pressures.

Lactose tolerance

Around 11,000 years ago, as agriculture was replacing hunting and gathering in the Middle East, people invented ways to reduce the concentrations of lactose in milk by fermenting it to make yogurt and cheese. People lost the ability to digest lactose as they matured and as such lost the ability to consume milk. Thousands of years later, a genetic mutation enabled people living in Europe at the time to continue producing lactase, an enzyme that digests lactose, throughout their lives, allowing them to drink milk after weaning and survive bad harvests.

Today, lactase persistence can be found in 90% or more of the populations in Northwestern and Northern Central Europe, and in pockets of Western and Southeastern Africa, Saudi Arabia, and South Asia. It is not as common in Southern Europe (40%) because Neolithic farmers had already settled there before the mutation existed. It is rarer in inland Southeast Asia and Southern Africa. While all Europeans with lactase persistence share a common ancestor for this ability, pockets of lactase persistence outside Europe are likely due to separate mutations. The European mutation, called the LP allele, is traced to modern-day Hungary, 7,500 years ago. In the twenty-first century, about 35% of the human population is capable of digesting lactose after the age of seven or eight. Prior this mutation, dairy farming was already widespread in Europe.

A Finnish research team reported that the European mutation that allows for lactase persistence is not found among the milk-drinking and dairy-farming Africans, however. Sarah Tishkoff and her students confirmed this by analyzing DNA samples from Tanzania, Kenya, and Sudan, where lactase persistence evolved independently. The uniformity of the mutations surrounding the lactase gene suggests that lactase persistence spread rapidly throughout this part of Africa. According to Tishkoff's data, this mutation first appeared between 3,000 and 7,000 years ago. This mutation provides some protection against drought and enables people to drink milk without diarrhea, which causes dehydration.

Lactase persistence is a rare ability among mammals. Because it involves a single gene, it is a simple example of convergent evolution in humans. Other examples of convergent evolution, such as the light skin of Europeans and East Asians or the various means of resistance to malaria, are much more complicated.

Skin color

The light skin pigmentation characteristic of modern Europeans is estimated to have spread across Europe in a "selective sweep" during the Mesolithic (5,000 years ago). Signals for selection in favor of light skin among Europeans was one of the most pronounced, comparable to those for resistance to malaria or lactose tolerance. However, Dan Ju and Ian Mathieson caution in a study addressing 40,000 years of modern human history, "we can assess the extent to which they carried the same light pigmentation alleles that are present today," but explain that c. 40,000 BP Early Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers "may have carried different alleles that we cannot now detect", and as a result "we cannot confidently make statements about the skin pigmentation of ancient populations.”

Eumelanin, which is responsible for pigmentation in human skin, protects against ultraviolet radiation while also limiting vitamin D synthesis. Variations in skin color, due to the levels of melanin, are caused by at least 25 different genes, and variations evolved independently of each other to meet different environmental needs. Over the millennia, human skin colors have evolved to be well-suited to their local environments. Having too much melanin can lead to vitamin D deficiency and bone deformities while having too little makes the person more vulnerable to skin cancer. Indeed, Europeans have evolved lighter skin in order to combat vitamin D deficiency in regions with low levels of sunlight. Today, they and their descendants in places with intense sunlight such as Australia are highly vulnerable to sunburn and skin cancer. On the other hand, Inuit have a diet rich in vitamin D and consequently have not needed lighter skin.

Eye color

Blue eyes are an adaptation for living in regions where the amounts of light are limited because they allow more light to come in than brown eyes. They also seem to have undergone both sexual and frequency-dependent selection. A research program by geneticist Hans Eiberg and his team at the University of Copenhagen from the 1990s to 2000s investigating the origins of blue eyes revealed that a mutation in the gene OCA2 is responsible for this trait. According to them, all humans initially had brown eyes and the OCA2 mutation took place between 6,000 and 10,000 years ago. It dilutes the production of melanin, responsible for the pigmentation of human hair, eye, and skin color. The mutation does not completely switch off melanin production, however, as that would leave the individual with a condition known as albinism. Variations in eye color from brown to green can be explained via the variation in the amounts of melanin produced in the iris. While brown-eyed individuals share a large area in their DNA controlling melanin production, blue-eyed individuals have only a small region. By examining mitochondrial DNA of people from multiple countries, Eiberg and his team concluded blue-eyed individuals all share a common ancestor.

In 2018, an international team of researchers from Israel and the United States announced their genetic analysis of 6,500-year-old excavated human remains in Israel's Upper Galilee region revealed a number of traits not found in the humans who had previously inhabited the area, including blue eyes. They concluded that the region experienced a significant demographic shift 6,000 years ago due to migration from Anatolia and the Zagros mountains (in modern-day Turkey and Iran) and that this change contributed to the development of the Chalcolithic culture in the region.

Bronze Age to Medieval Era

Resistance to malaria is a well-known example of recent human evolution. This disease attacks humans early in life. Thus humans who are resistant enjoy a higher chance of surviving and reproducing. While humans have evolved multiple defenses against malaria, sickle cell anemia—a condition in which red blood cells are deformed into sickle shapes, thereby restricting blood flow—is perhaps the best known. Sickle cell anemia makes it more difficult for the malarial parasite to infect red blood cells. This mechanism of defense against malaria emerged independently in Africa and in Pakistan and India. Within 4,000 years it has spread to 10–15% of the populations of these places. Another mutation that enabled humans to resist malaria that is strongly favored by natural selection and has spread rapidly in Africa is the inability to synthesize the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, or G6PD.

A combination of poor sanitation and high population densities proved ideal for the spread of contagious diseases which was deadly for the residents of ancient cities. Evolutionary thinking would suggest that people living in places with long-standing urbanization dating back millennia would have evolved resistance to certain diseases, such as tuberculosis and leprosy. Using DNA analysis and archeological findings, scientists from the University College London and the Royal Holloway studied samples from 17 sites in Europe, Asia, and Africa. They learned that, indeed, long-term exposure to pathogens has led to resistance spreading across urban populations. Urbanization is therefore a selective force that has influenced human evolution. The allele in question is named SLC11A1 1729+55del4. Scientists found that among the residents of places that have been settled for thousands of years, such as Susa in Iran, this allele is ubiquitous whereas in places with just a few centuries of urbanization, such as Yakutsk in Siberia, only 70–80% of the population have it.

Evolution to resist infection of pathogens also increased inflammatory disease risk in post-Neolithic Europeans over the last 10,000 years. A study of ancient DNA estimated nature, strength, and time of onset of selections due to pathogens and also found that "the bulk of genetic adaptation occurred after the start of the Bronze Age, <4,500 years ago".

Adaptations have also been found in modern populations living in extreme climatic conditions such as the Arctic, as well as immunological adaptations such as resistance against prion caused brain disease in populations practicing mortuary cannibalism, or the consumption of human corpses. Inuit have the ability to thrive on the lipid-rich diets consisting of Arctic mammals. Human populations living in regions of high altitudes, such as the Tibetan Plateau, Ethiopia, and the Andes benefit from a mutation that enhances the concentration of oxygen in their blood. This is achieved by having more capillaries, increasing their capacity for carrying oxygen. This mutation is believed to be around 3,000 years old.

A recent adaptation has been proposed for the Austronesian Sama-Bajau, also known as the Sea Gypsies or Sea Nomads, developed under selection pressures associated with subsisting on free-diving over the past thousand years or so. As maritime hunter-gatherers, the ability to dive for long periods of times plays a crucial role in their survival. Due to the mammalian dive reflex, the spleen contracts when the mammal dives and releases oxygen-carrying red blood cells. Over time, individuals with larger spleens were more likely to survive the lengthy free-dives, and thus reproduce. By contrast, communities centered around farming show no signs of evolving to have larger spleens. Because the Sama-Bajau show no interest in abandoning this lifestyle, there is no reason to believe further adaptation will not occur.

Advances in the biology of genomes have enabled geneticists to investigate the course of human evolution within centuries. Jonathan Pritchard and a postdoctoral fellow, Yair Field, counted the singletons, or changes of single DNA bases, which are likely to be recent because they are rare and have not spread throughout the population. Since alleles bring neighboring DNA regions with them as they move around the genome, the number of singletons can be used to roughly estimate how quickly the allele has changed its frequency. This approach can unveil evolution within the last 2,000 years or a hundred human generations. Armed with this technique and data from the UK10K project, Pritchard and his team found that alleles for lactase persistence, blond hair, and blue eyes have spread rapidly among Britons within the last two millennia or so. Britain's cloudy skies may have played a role in that the genes for light hair could also cause light skin, reducing the chances of vitamin D deficiency. Sexual selection could also favor blond hair. The technique also enabled them to track the selection of polygenic traits—those affected by a multitude of genes, rather than just one—such as height, infant head circumferences, and female hip sizes (crucial for giving birth). They found that natural selection has been favoring increased height and larger head and female hip sizes among Britons. Moreover, lactase persistence showed signs of active selection during the same period. However, evidence for the selection of polygenic traits is weaker than those affected only by one gene.

A 2012 paper studied the DNA sequence of around 6,500 Americans of European and African descent and confirmed earlier work indicating that the majority of changes to a single letter in the sequence (single nucleotide variants) were accumulated within the last 5,000-10,000 years. Almost three quarters arose in the last 5,000 years or so. About 14% of the variants are potentially harmful, and among those, 86% were 5,000 years old or younger. The researchers also found that European Americans had accumulated a much larger number of mutations than African Americans. This is likely a consequence of their ancestors' migration out of Africa, which resulted in a genetic bottleneck; there were few mates available. Despite the subsequent exponential growth in population, natural selection has not had enough time to eradicate the harmful mutations. While humans today carry far more mutations than their ancestors did 5,000 years ago, they are not necessarily more vulnerable to illnesses because these might be caused by multiple mutations. It does, however, confirm earlier research suggesting that common diseases are not caused by common gene variants. In any case, the fact that the human gene pool has accumulated so many mutations over such a short period of time—in evolutionary terms—and that the human population has exploded in that time mean that humanity is more evolvable than ever before. Natural selection might eventually catch up with the variations in the gene pool, as theoretical models suggest that evolutionary pressures increase as a function of population size.

Early Modern Period to present

A study published in 2021 states that the populations of the Cape Verde islands off the coast of West Africa have speedily evolved resistance to malaria within roughly the last 20 generations, since the start of human habitation there. As expected, the residents of the Island of Santiago, where malaria is most prevalent, show the highest prevalence of resistance. This is one of the most rapid cases of change to the human genome measured.

Geneticist Steve Jones told the BBC that during the sixteenth century, only a third of English babies survived until the age of 21, compared to 99% in the twenty-first century. Medical advances, especially those made in the twentieth century, made this change possible. Yet while people from the developed world today are living longer and healthier lives, many are choosing to have just a few or no children at all, meaning evolutionary forces continue to act on the human gene pool, just in a different way.

Natural selection affects only 8% of the human genome, meaning mutations in the remaining parts of the genome can change their frequency by pure chance through neutral selection. If natural selective pressures are reduced, then more mutations survive, which could increase their frequency and the rate of evolution. For humans, a large source of heritable mutations is sperm; a man accumulates more and more mutations in his sperm as he ages. Hence, men delaying reproduction can affect human evolution.

A 2012 study led by Augustin Kong suggests that the number of de novo (new) mutations increases by about two per year of delayed reproduction by the father and that the total number of paternal mutations doubles every 16.5 years.

For a long time, medicine has reduced the fatality of genetic defects and contagious diseases, allowing more and more humans to survive and reproduce, but it has also enabled maladaptive traits that would otherwise be culled to accumulate in the gene pool. This is not a problem as long as access to modern healthcare is maintained. But natural selective pressures will mount considerably if that is taken away. Nevertheless, dependence on medicine rather than genetic adaptations will likely be the driving force behind humanity's fight against diseases for the foreseeable future. Moreover, while the introduction of antibiotics initially reduced the mortality rates due to infectious diseases by significant amounts, abuse has led to the rise of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, making many illnesses major causes of death once again.

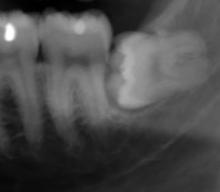

Human jaws and teeth have been shrinking in proportion with the decrease in body size in the last 30,000 years as a result of new diets and technology. There are many individuals today who do not have enough space in their mouths for their third molars (or wisdom teeth) due to reduced jaw sizes. In the twentieth century, the trend toward smaller teeth appeared to have been slightly reversed due to the introduction of fluoride, which thickens dental enamel, thereby enlarging the teeth.

Recent research suggests that menopause is evolving to occur later. Other reported trends appear to include lengthening of the human reproductive period and reduction in cholesterol levels, blood glucose and blood pressure in some populations.

Population geneticist Emmanuel Milot and his team studied recent human evolution in an isolated Canadian island using 140 years of church records. They found that selection favored younger age at first birth among women. In particular, the average age at first birth of women from Coudres Island (Île aux Coudres), 80 km (50 mi) northeast of Québec City, decreased by four years between 1800 and 1930. Women who started having children sooner generally ended up with more children in total who survive until adulthood. In other words, for these French-Canadian women, reproductive success was associated with lower age at first childbirth. Maternal age at first birth is a highly heritable trait.

Human evolution continues during the modern era, including among industrialized nations. Things like access to contraception and the freedom from predators do not stop natural selection. Among developed countries, where life expectancy is high and infant mortality rates are low, selective pressures are the strongest on traits that influence the number of children a human has. It is speculated that alleles influencing sexual behavior would be subject to strong selection, though the details of how genes can affect said behavior remain unclear.

Historically, as a by-product of the ability to walk upright, humans evolved to have narrower hips and birth canals and to have larger heads. Compared to other close relatives such as chimpanzees, childbirth is a highly challenging and potentially fatal experience for humans. Thus began an evolutionary tug-of-war (see Obstetrical dilemma). For babies, having larger heads proved beneficial as long as their mothers' hips were wide enough. If not, both mother and child typically died. This is an example of balancing selection, or the removal of extreme traits. In this case, heads that were too large or hips that were too small were selected against. This evolutionary tug-of-war attained an equilibrium, making these traits remain more or less constant over time while allowing for genetic variation to flourish, thus paving the way for rapid evolution should selective forces shift their direction.

All this changed in the twentieth century as Cesarean sections (or C-sections) became safer and more common in some parts of the world. Larger head sizes continue to be favored while selective pressures against smaller hip sizes have diminished. Projecting forward, this means that human heads would continue to grow while hip sizes would not. As a result of increasing fetopelvic disproportion, C-sections would become more and more common in a positive feedback loop, though not necessarily to the extent that natural childbirth would become obsolete.

Paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner of the Smithsonian Institution noted that cultural factors could play a role in the widely different rates of C-sections across the developed and developing worlds. Daghni Rajasingam of the Royal College of Obstetricians observed that the increasing rates of diabetes and obesity among women of reproductive age also boost the demand for C-sections. Biologist Philipp Mitteroecker from the University of Vienna and his team estimated that about six percent of all births worldwide were obstructed and required medical intervention. In the United Kingdom, one quarter of all births involved the C-section while in the United States, the number was one in three. Mitteroecker and colleagues discovered that the rate of C-sections has gone up 10% to 20% since the mid-twentieth century. They argued that because the availability of safe Cesarean sections significantly reduced maternal and infant mortality rates in the developed world, they have induced an evolutionary change. However, "It's not easy to foresee what this will mean for the future of humans and birth," Mitteroecker told The Independent. This is because the increase in baby sizes is limited by the mother's metabolic capacity and modern medicine, which makes it more likely that neonates who are born prematurely or are underweight to survive.

Researchers participating in the Framingham Heart Study, which began in 1948 and was intended to investigate the cause of heart disease among women and their descendants in Framingham, Massachusetts, found evidence for selective pressures against high blood pressure due to the modern Western diet, which contains high amounts of salt, known for raising blood pressure. They also found evidence for selection against hypercholesterolemnia, or high levels of cholesterol in the blood. Evolutionary geneticist Stephen Stearns and his colleagues reported signs that women were gradually becoming shorter and heavier. Stearns argued that human culture and changes humans have made on their natural environments are driving human evolution rather than putting the process to a halt. The data indicates that the women were not eating more; rather, the ones who were heavier tended to have more children. Stearns and his team also discovered that the subjects of the study tended to reach menopause later; they estimated that if the environment remains the same, the average age at menopause will increase by about a year in 200 years, or about ten generations. All these traits have medium to high heritability. Given the starting date of the study, the spread of these adaptations can be observed in just a few generations.

By analyzing genomic data of 60,000 individuals of Caucasian descent from Kaiser Permanente in Northern California, and of 150,000 people in the UK Biobank, evolutionary geneticist Joseph Pickrell and evolutionary biologist Molly Przeworski were able to identify signs of biological evolution among living human generations. For the purposes of studying evolution, one lifetime is the shortest possible time scale. An allele associated with difficulty withdrawing from tobacco smoking dropped in frequency among the British but not among the Northern Californians. This suggests that heavy smokers—who were common in Britain during the 1950s but not in Northern California—were selected against. A set of alleles linked to later menarche was more common among women who lived for longer. An allele called ApoE4, linked to Alzheimer's disease, fell in frequency as carriers tended to not live for very long. In fact, these were the only traits that reduced life expectancy Pickrell and Przeworski found, which suggests that other harmful traits probably have already been eradicated. Only among older people are the effects of Alzheimer's disease and smoking visible. Moreover, smoking is a relatively recent trend. It is not entirely clear why such traits bring evolutionary disadvantages, however, since older people have already had children. Scientists proposed that either they also bring about harmful effects in youth or that they reduce an individual's inclusive fitness, or the tendency of organisms that share the same genes to help each other. Thus, mutations that make it difficult for grandparents to help raise their grandchildren are unlikely to propagate throughout the population. Pickrell and Przeworski also investigated 42 traits determined by multiple alleles rather than just one, such as the timing of puberty. They found that later puberty and older age of first birth were correlated with higher life expectancy.

Larger sample sizes allow for the study of rarer mutations. Pickrell and Przeworski told The Atlantic that a sample of half a million individuals would enable them to study mutations that occur among only 2% of the population, which would provide finer details of recent human evolution. While studies of short time scales such as these are vulnerable to random statistical fluctuations, they can improve understanding of the factors that affect survival and reproduction among contemporary human populations.

Evolutionary geneticist Jaleal Sanjak and his team analyzed genetic and medical information from more than 200,000 women over the age of 45 and 150,000 men over the age of 50—people who have passed their reproductive years—from the UK Biobank and identified 13 traits among women and ten among men that were linked to having children at a younger age, having a higher body-mass index, fewer years of education, and lower levels of fluid intelligence, or the capacity for logical reasoning and problem solving. Sanjak noted, however, that it was not known whether having children actually made women heavier or being heavier made it easier to reproduce. Because taller men and shorter women tended to have more children and because the genes associated with height affect men and women equally, the average height of the population will likely remain the same. Among women who had children later, those with higher levels of education had more children.

Evolutionary biologist Hakhamanesh Mostafavi led a 2017 study that analyzed data of 215,000 individuals from just a few generations in the United Kingdom and the United States and found a number of genetic changes that affect longevity. The ApoE allele linked to Alzheimer's disease was rare among women aged 70 and over while the frequency of the CHRNA3 gene associated with smoking addiction among men fell among middle-aged men and up. Because this is not itself evidence of evolution, since natural selection only cares about successful reproduction not longevity, scientists have proposed a number of explanations. Men who live longer tend to have more children. Men and women who survive until old age can help take care of both their children and grandchildren, in benefits their descendants down the generations. This explanation is known as the grandmother hypothesis. It is also possible that Alzheimer's disease and smoking addiction are also harmful earlier in life, but the effects are more subtle and larger sample sizes are required in order to study them. Mostafavi and his team also found that mutations causing health problems such as asthma, having a high body-mass index and high cholesterol levels were more common among those with shorter lifespans while mutations leading to delayed puberty and reproduction were more common among long living individuals. According to geneticist Jonathan Pritchard, while the link between fertility and longevity was identified in previous studies, those did not entirely rule out the effects of educational and financial status—people who rank high in both tend to have children later in life; this seems to suggest the existence of an evolutionary trade-off between longevity and fertility.

In South Africa, where large numbers of people are infected with HIV, some have genes that help them combat this virus, making it more likely that they would survive and pass this trait onto their children. If the virus persists, humans living in this part of the world could become resistant to it in as little as hundreds of years. However, because HIV evolves more quickly than humans, it will more likely be dealt with technologically rather than genetically.

A 2017 study by researchers from Northwestern University unveiled a mutation among the Old Order Amish living in Berne, Indiana, that suppressed their chances of having diabetes and extends their life expectancy by about ten years on average. That mutation occurred in the gene called Serpine1, which codes for the production of the protein PAI-1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor), which regulates blood clotting and plays a role in the aging process. About 24% of the people sampled carried this mutation and had a life expectancy of 85, higher than the community average of 75. Researchers also found the telomeres—non-functional ends of human chromosomes—of those with the mutation to be longer than those without. Because telomeres shorten as the person ages, those with longer telomeres tend to live longer. At present, the Amish live in 22 U.S. states plus the Canadian province of Ontario. They live simple lifestyles that date back centuries and generally insulate themselves from modern North American society. They are mostly indifferent towards modern medicine, but scientists do have a healthy relationship with the Amish community in Berne. Their detailed genealogical records make them ideal subjects for research.

In 2020, Teghan Lucas, Maciej Henneberg, Jaliya Kumaratilake gave evidence that a growing share of the human population retained the median artery in their forearms. This structure forms during fetal development but dissolves once two other arteries, the radial and ulnar arteries, develop. The median artery allows for more blood flow and could be used as a replacement in certain surgeries. Their statistical analysis suggested that the retention of the median artery was under extremely strong selection within the last 250 years or so. People have been studying this structure and its prevalence since the eighteenth century.

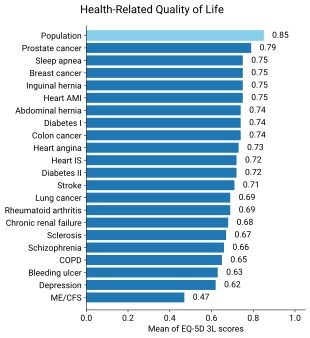

Multidisciplinary research suggests that ongoing evolution could help explain the rise of certain medical conditions such as autism and autoimmune disorders. Autism and schizophrenia may be due to genes inherited from the mother and the father which are over-expressed and which fight a tug-of-war in the child's body. Allergies, asthma, and autoimmune disorders appear linked to higher standards of sanitation, which prevent the immune systems of modern humans from being exposed to various parasites and pathogens the way their ancestors' were, making them hypersensitive and more likely to overreact. The human body is not built from a professionally engineered blue print but a system shaped over long periods of time by evolution with all kinds of trade-offs and imperfections. Understanding the evolution of the human body can help medical doctors better understand and treat various disorders. Research in evolutionary medicine suggests that diseases are prevalent because natural selection favors reproduction over health and longevity. In addition, biological evolution is slower than cultural evolution and humans evolve more slowly than pathogens.

Whereas in the ancestral past, humans lived in geographically isolated communities where inbreeding was rather common, modern transportation technologies have made it much easier for people to travel great distances and facilitated further genetic mixing, giving rise to additional variations in the human gene pool. It also enables the spread of diseases worldwide, which can have an effect on human evolution. Furthermore, climate change may trigger the mass migration of not just humans but also diseases affecting humans. Besides the selection and flow of genes and alleles, another mechanism of biological evolution is epigenetics, or changes not to the DNA sequence itself, but rather the way it is expressed. Scientists already know that chronic illnesses and stress are epigenetic mechanisms.