Locations in the Solar System besides the Earth have appeared as settings in fiction since at least classical antiquity, initially as an extension of the established literary form of the imaginary voyage to exotic locations ostensibly on Earth. The motif then largely fell out of use for over a millennium and did not become commonplace again until the 1600s with the Copernican Revolution. For most of literary history the principal extraterrestrial location was the Moon; in the late 1800s, advances in astronomy led to Mars becoming more popular. The discovery of Uranus in 1781 and Neptune in 1846, as well the first asteroids in the early 1800s, had little immediate impact on fiction. The main theme has been visits by humans to the Moon or one of the planets, where they would often find native lifeforms. Alien societies commonly serve as vehicles for satire or utopian fiction. Less frequently, Earth itself has been visited by inhabitants of the other planets, or even subjected to an alien invasion.

History

Ancient depictions

Locations in the Solar System besides the Earth have appeared as settings in fiction since at least classical antiquity. The conceit of journeying to other worlds grew out of the established literary form of the imaginary voyage to exotic locations ostensibly on Earth, typified by Homer's Odyssey. The earliest stories visiting outer space visited other parts of the Solar System—in particular, the Moon. Science fiction scholar Adam Roberts writes that for the Ancient Greeks, specifically, the Moon and Sun could be thought of as part of the earthly realm of the sky, rather than the divine realm of the heavens, unlike the stars; Arthur C. Clarke comments that the classical planets visible to the naked eye as point sources of light were thought of as wandering stars, which made visiting them equally unthinkable. Speculation that the Moon might be inhabited appears in the nonfiction writings of Philolaus and Plutarch, among others.[ As the literary record from this era is very incomplete, there is uncertainty about the earliest interplanetary voyages in fiction; Roberts and science fiction historian Sam Moskowitz both posit that numerous such stories predating the known ones may have been lost to time. The earliest known example is Antonius Diogenes's Of the Wonderful Things Beyond Thule, which includes a journey on foot that reaches the Moon by going northwards. It is a lost literary work of uncertain date—with estimates ranging from the 300s BCE to the 100s CE—known only through a brief summary in Photius's c. 870 work Bibliotheca. The oldest surviving work of this kind is either of two stories by Lucian of Samosata from c. 160–180 CE: Icaromenippus and True History. In Icaromenippus, the Cynic philosopher Menippus, inspired by the story of Icarus, attaches bird wings to his arms and flies to the Moon to get a better vantage point to resolve the question of the shape of the Earth. True History is a parody of fanciful travellers' tales—in the story, a ship is swept to the Moon by a whirlwind, and the all-male lunar inhabitants are found to be at war with the inhabitants of the Sun over the colonization of the "Morning Star"; science fiction scholar Gary Westfahl considers this reference to Venus the first appearance of any planet in the genre. After Lucian, the interplanetary voyage largely fell out of use for over a millennium—as did, according to Roberts, the genre of science fiction as a whole a few centuries later at the start of the so-called Dark Ages.

Copernican Revolution

Interplanetary voyages came into vogue again with the Copernican Revolution, a gradual process that began with the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus's 1543 scientific work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) positing that the planets revolve around the Sun rather than around the Earth and continued until Isaac Newton's work on the laws of motion and gravitation provided the necessary mathematical foundation to fully explain Copernicus's model more than a century later. There were nevertheless some antecedents. In medieval Europe, Dante Alighieri's c. 1320 poem the Divine Comedy visits the Moon and portrays it as the lowest level of Heaven,while in Ludovico Ariosto's poem Orlando Furioso (first version published in 1516, final version in 1532) the Moon is where items lost on Earth end up and it is visited by Astolfo to retrieve the sanity of the title character; Roberts views these narratives as separate from the science-fictional tradition of voyages into outer space inasmuch as they portray the other worlds as supernatural rather than material realms—in particular, Roberts contrasts them with Giambattista Marino's 1622 epic L'Adone, which, although it retains the then-outdated geocentric model in visiting the Moon, Mercury, and Venus, nevertheless treats them as worlds qualitatively akin to the Earth. Outside of Western literature, the c. 800s–900s Japanese folktale The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter is about a lunar princess on Earth who eventually returns to the Moon.

The first fictional lunar excursion with a science-based approach was written by Johannes Kepler, an important figure of the Copernican Revolution who provided the key insight that planetary orbits are not circular as had been previously assumed but elliptical and introduced a set of three laws of planetary motion. Kepler's Somnium, sometimes considered the first science fiction novel, was written chiefly to explain and advance the Copernican model. The book describes different populations of intelligent life on the near and far side of the Moon, both with adaptations to the month-long cycle of day and night based on exobiological considerations, and their astronomical perspective: for instance, the inhabitants of the near side are able to determine their location on the lunar surface and the time of day by observing the position of the Earth in the sky and the phase of the Earth, respectively. The first draft was written in 1593, before being revised in 1609 and then expanded until Kepler's death in 1630, ultimately being published posthumously in 1634; Karl Siegfried Guthke notes that this means that—contrary to the perceptions of some scholars—the story narrowly predates the invention of the telescope. Also in 1634, the first English-language translation of Lucian's True History by Francis Hickes was published; Moskowitz credits this with launching the literary trend of interplanetary voyages, while Westfahl more modestly speculates that writers of such stories may have drawn inspiration from it, and Brian Aldiss, in the 1973 book Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction, comments that Lucian undoubtedly influenced later writers but ultimately concludes that the more general trends of the Age of Exploration were largely responsible for the profusion of fictional voyages to the Moon.

As no plausible method of space travel had yet been conceived, these stories employed supernatural or otherwise intentionally unrealistic means of transport, or had the characters visit the remote locations in dreams. Kepler's Somnium, although it depicts the conditions on the Moon in accordance with the most up-to-date science available at the time, nevertheless employs a daemon to make the voyage there. Francis Godwin's posthumously-published 1638 novel The Man in the Moone uses migratory birds to reach the Moon, where a utopia is discovered. Godwin's book was both popular and influential, and inspired John Wilkins to add discussion of the practical considerations of travelling to the Moon to the third edition of his 1638 speculative nonfiction work The Discovery of a World in the Moone, published in 1640; Wilkins's work also contains an early reference to colonization of the Moon, treating it as a natural corollary to solving the transport issue. Cyrano de Bergerac's posthumously-published 1657 novel Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon and its 1662 sequel Comical History of the States and Empires of the Sun depict journeys to the Moon and Sun—both of which are found to be inhabited, with the protagonist of Godwin's novel being encountered on the Moon—using various devices, including the first fictional rocket.

The plurality of worlds

In the late 1500s and early 1600s, the idea of the plurality of worlds—that other celestial bodies in the Solar System, and maybe also outside of it, are worlds like the Earth and perhaps even inhabited—was controversial especially in the Catholic parts of Europe because it appeared to conflict with established religious views that asserted the primacy of Earth and humanity; Giordano Bruno was convicted of heresy and executed in 1600 in part for this belief. By the mid-1600s, however, the controversy had subsided to a degree and the topic appeared in the writings of Cyrano and others; by the end of the century, it was largely accepted. Two works played an important role in popularizing the concept: Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle's 1686 work Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes (Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds) and Christiaan Huygens's posthumously-published 1698 work Cosmotheoros. Both are primarily literary rather than scientific works; Guthke takes the apparent broad appeal of Cosmotheoros as evidence that contemporary readers viewed it mainly as science fiction. There are many similarities between the two works, but they differ in their conception of the inhabitants of the other planets: Fontenelle describes diverse and fundamentally nonhuman lifeforms adapted to the different environmental conditions of the Moon and planets in the Solar System, while Huygens describes beings that are essentially human on the grounds that Earth ought not be unique in this regard. Besides depicting a plurality of worlds in the Solar System, Fontenelle's work also popularized the related notion that other stars might have planetary systems of their own just like the Sun; while it dismisses the Sun and stars as possible abodes of life, it asserts that there are unseen planets orbiting the fixed stars that are also inhabited.

Through the 1700s

Fiction literature about the Solar System continued to mainly take the form of satires and utopian fiction up until the late 1800s; Roger Lancelyn Green writes that the scientific advancements of the time may help explain the dominance of the satirical mode throughout the latter part of the 1600s and the 1700s, while J. O. Bailey writes that the satire "deepened and became more philosophical" in this period, whereas Kepler's approach of adhering to known facts of science was only emulated sporadically. Westfahl comments that up through the 1700s, authors "invariably imagined that other planets would have humanlike inhabitants" and used extraterrestrial locations for social commentary, as opposed to conceiving of truly alien societies as became common later in the history of science fiction. Early feminist science fiction writer Margaret Cavendish's 1666 novel The Blazing World—which describes another planet that is joined to the Earth at the North Pole—contains both utopian elements and satire of the Royal Society, the scientific establishment of the day. Gabriel Daniel's 1690 novel A Voyage to the World of Cartesius uses a voyage to the Moon and beyond to satirize the ideas of René Descartes, showing them to produce absurd results (such as the stars being invisible and tides not existing) and depicting Descartes's spirit as occupied with correcting God's errors. Trips to the Moon serve as vehicles for satire of the British political system in Daniel Defoe's 1705 novel The Consolidator and the South Sea Bubble in Samuel Brunt's 1727 novel A Voyage to Cacklogallinia. Among the rare exceptions to the trend are Eberhard Christian Kindermann's 1744 story "Die Geschwinde Reise", which describes a journey to a moon of Mars the author mistakenly believed he had discovered, and Chevalier de Béthune's 1750 novel Relation du Monde de Mercure, the first novel focused specifically on Mercury.

Cyrano's example of employing rocketry to traverse space was not followed. Various means of transport were explored, but plausibility remained elusive; Brian Stableford, in the 2006 reference work Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia, describes it as "an awkward challenge" and comments that flying machines appeared no more realistic than other means of flight in an era before aeronautics. The planet in Cavendish's The Blazing World is reachable on foot as in Of the Wonderful Things Beyond Thule. The anonymously-published 1690 work Selenographia: The Lunarian, or Newes from the World in the Moon to the Lunaticks of This World uses a kite to reach the Moon, while David Russen's 1703 work Iter Lunare envisions launch by an enormous spring-powered catapult and anticipates the risk of missing the Moon, and Defoe's The Consolidator uses a moving-wing machine powered by an internal combustion engine of sorts. The opposite approach of aliens visiting Earth first appeared in Voltaire's 1752 work Micromégas, where one alien from Sirius and another from Saturn come to Earth, but this remained a rare motif. The invention of the balloon in 1783 made flight inside the Earth's atmosphere more popular at the expense of spaceflight, and demonstrated that exposure to high-altitude conditions is not survivable for unprotected humans, but the balloon nevertheless became a common vehicle for interplanetary voyages, a role it continued to play as late as the anonymously published 1873 novel A Narrative of the Travels and Adventures of Paul Aermont among the Planets.

Verisimilitude

By the second half of the century [...] stories of space-travel became both more common and more scientific. No doubt the great engineering achievements of the Victorian age had produced a feeling of optimism: so much had already been accomplished that perhaps even the bridging of space was no longer a totally impossible dream.

The 1800s saw the emergence of a greater degree of verisimilitude in stories about space travel, especially in the latter part of the century. George Tucker's 1827 novel A Voyage to the Moon (published under the pseudonym Joseph Atterley) is the earliest known example of anti-gravity both being treated from a scientific rather than supernatural angle and being employed for interplanetary travel. Edgar Allan Poe was a student at the University of Virginia in 1826 while Tucker was a professor there and is known to have read his book; in 1835, Poe published a story of his own about a lunar journey: "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall". Poe's story contains a mixture of elements that lend credibility to the narrative and whimsical ones, and the preface includes a facetious request for increased verisimilitude in other authors' tales of space travel. A promised sequel to "Hans Pfaall" never materialized, possibly due to the publication of Richard Adams Locke's so-called "Great Moon Hoax" a few weeks later, which claimed that John Herschel had discovered life on the Moon through a telescope. The pseudonymous Chrysostom Trueman's 1864 novel The History of a Voyage to the Moon reuses the anti-gravity mechanism of spaceflight and devotes more than half of its length to the details of the spaceship and journey. Achille Eyraud's 1865 novel Voyage à Venus, the first novel focused specifically on Venus, was also one of the first[g] since Cyrano's Comical History to use a reaction engine or rocket propulsion for space travel—here, a water-based version. Taking Poe's preface at face value, Jules Verne strived to write of a believable lunar journey. In Verne's 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon and its 1870 sequel Around the Moon, a vessel is launched into space by a large cannon before circling the Moon and returning to Earth. On the mode of travel, Clarke notes that the initial ballistic launch would in reality not be survivable, and that while the spaceship uses rockets for steering it apparently did not occur to Verne that they could be used for the rest of the journey as well. Clarke further posits that the absence of a Moon landing in the story may be explained by the lack of a plausible way to return to Earth thereafter.

The ascendancy of Mars

The Moon remained the most popular celestial object in fiction, with the Sun a distant second, until Mars overtook them both in the late 1800s. Although Uranus had been discovered in 1781 and Neptune in 1846, neither received much attention from writers. Similarly, the first asteroids were discovered at the beginning of the 1800s, but they made scant appearances in fiction for the rest of the century. Two major factors contributed to Mars replacing the Moon as the most favoured location: advances in astronomy had determined that the Moon was not habitable, while Mars on the contrary appeared increasingly likely to be so. In particular, during the opposition of Mars in 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli announced the discovery of linear structures he dubbed canali (literally channels, but widely translated as canals) on the Martian surface. These purported Martian canals were variously interpreted as optical illusions (as they were later determined to be), natural features, or artificial constructs; Percival Lowell popularized the notion that they were vast engineering projects by an advanced Martian civilization through a series of non-fiction books published between 1895 and 1908. The first novel focused specifically on Mars was Percy Greg's 1880 novel Across the Zodiac, which features a form of anti-gravity dubbed "apergy"; the term was later adopted in many other works—both fiction and non-fiction—including John Jacob Astor IV's 1894 novel A Journey in Other Worlds, which visits Jupiter and Saturn. Anti-gravity voyages to Mars also appear in Hugh MacColl's 1889 novel Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet, Robert Cromie's 1890 novel A Plunge into Space, and Gustavus W. Pope's 1894 novel Journey to Mars.

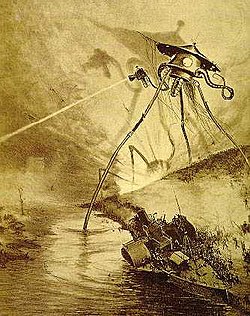

Two 1897 novels—Kurd Lasswitz's Auf zwei Planeten and H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds—used Martians that are more advanced than humans to introduce an entirely new concept: the alien invasion of Earth. In Auf zwei Planeten the Martians are human-like creatures who initially have benevolent intentions for Earth but gradually end up acting as an occupying colonial power, whereas the Martians in The War of the Worlds are utterly inhuman and bent on conquest. Both novels had a big impact: Auf zwei Planeten was translated into several languages and was highly influential in Continental Europe—but did not receive a translation into English until the 1970s, which limited its impact in the Anglosphere—while The War of the Worlds is considered one of the most influential works in the history of science fiction and has received multitudes of adaptations, parodies, and sequels by other authors.

Besides Mars, the Moon still occasionally appeared as a setting during this time, though it was largely relegated to children's stories and fairy tales. One of the exceptions was Wells's 1901 novel The First Men in the Moon, which reaches the Moon by an anti-gravity material called Cavorite and places life on the inside of the Moon rather than on the visibly-lifeless surface; the first science fiction film, Georges Méliès's 1902 short film Le voyage dans la lune, is loosely based on both Wells's lunar voyage and Verne's. Venus also appeared in works like John Munro's 1897 novel A Trip to Venus and Garrett P. Serviss's 1909 novel A Columbus of Space, but never reached the same level of popularity as Mars.

Barsoom and its offshoots dominated the interplanetary fiction of the first half of the century.

The interplanetary story in general, and Mars in particular, received an additional boost in popularity with Edgar Rice Burroughs's 1912–1943 Barsoom series beginning with A Princess of Mars. Barsoom, as this version Mars is known, is inhabited by a wide variety of exotic plants and creatures, including several different sentient races and an advanced civilization in decline; Westfahl describes it as "the most famous and well-developed Mars in science fiction". This depiction of Mars was inspired at least in part by Lowell's speculations, albeit paying scant attention to the scientific niceties surrounding the canal debate in favour of providing a suitable setting for exciting adventures. The stories and setting inspired many other authors such as Leigh Brackett to follow suit, albeit often using other locations in the Solar System and occasionally even beyond. Stableford comments in Anatomy of Wonder: A Critical Guide to Science Fiction that although the subgenre Burroughs thus launched is known as the planetary romance, the extraterrestrial setting was largely incidental—chosen not because other planets were believed to match the fictional descriptions, but because Earth was known not to.

The pulp era

Roberts writes that the first half of the 1900s was characterized by an increasing divergence between what might be termed "high art" and "popular culture"—the latter being represented in science fiction by the pulps. The first science fiction magazine was Amazing Stories, launched by Hugo Gernsback in 1926. This is commonly regarded as the beginning of the pulp era of science fiction, though by this time science fiction stories had already been regularly published in pulp magazines not specialized in the genre for decades (for instance, Serviss's A Columbus of Space and Burroughs's A Princess of Mars both first appeared in The All-Story Magazine), and the majority of science fiction continued to be published in general pulp magazines rather than science fiction ones. Gernsback found that interplanetary stories were his readership's favourite kind and decided to cater to this preference; one of his magazines, Wonder Stories Quarterly, bore the text "Interplanetary Stories" above the title from the Spring 1931 issue onward, and science fiction bibliographer E. F. Bleiler notes that two-thirds of the stories in these issues were interplanetary stories, with the vast majority of the remainder being "marginal or related". Moskowitz comments that Gernsback's actions, and his competitors' response in turn, thus hastened the evolution of "what was to become the most popular theme of science fiction".

The 1900s saw the emergence of a new subgenre—planetary romance—in works like Burroughs's Barsoom series. These stories flourished in the new pulp magazines, and the subgenre reached its peak between the 1930s and 1950s. Works of this kind typically portrayed Mars as a desert planet and Venus as covered in jungle. Eventually, the subgenre moved to locations outside of the Solar System.

Westfahl comments that "the 1930s were dominated by space operas set within the solar system", noting that in the catalogue of early science fiction works compiled by E. F. Bleiler and Richard Bleiler in the 1998 reference work Science-Fiction: The Gernsback Years, which lists all stories published in science fiction magazines between 1926 and 1936, Mars alone appears in more than 10% of the stories and Venus around 7%.

Works set on the Moon were less common due to a desire to depict

alien life and the apparent deadness of the lunar surface, though some

writers circumvented this issue by placing life underground as Wells had

in The First Men in the Moon; examples include Burroughs in the 1926 novel The Moon Maid, where the Moon is hollow, and P. Schuyler Miller in the 1931 short story "Dust of Destruction". This later became a popular way to dispense with the need for space suits in science fiction films in the 1950s and 1960s. Similarly, deep lunar valleys containing pockets of air capable of sustaining life appear in works such as Fritz Lang's 1929 film Frau im Mond and Victor Rousseau Emanuel's 1930 short story "The Lord of Space"; the concept had earlier appeared in George Griffith's 1901 novel A Honeymoon in Space. Other depictions of lunar lifeforms from this era confine it to the distant past or the far side of the Moon.

Pluto was discovered in 1930, and was relatively popular in fiction in the decades that followed as the apparent outermost planet of the Solar System. Its popularity exceeded that of Uranus and Neptune; Stableford posits that its initial popularity can at least in part be attributed to its then-recent discovery.

Stories involving the four giant planets of the outer Solar System—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—erroneously portrayed them as solid planets. This continued until the late 1950s.

Colonization of the Solar System became a recurring theme in this era. Although there had been a small number of antecedents such as Thomas Gray's 1737 poem "Luna Habilitatis", Andrew Blair's 1874 novel Annals of the Twenty-Ninth Century, and Robert William Cole's 1900 novel The Struggle for Empire: A Story of the Year 2236, the motif had not gained traction, and works like Olaf Stapledon's 1930 novel Last and First Men portrayed it as an act of utmost desperation.

This was also the era where stories stretching beyond the confines of the Solar System started appearing regularly; earlier examples had been few and far between.

Space Age

A clement twilight zone on a synchronously rotating Mercury, a swamp-and-jungle Venus, and a canal-infested Mars, while all classic science-fiction devices, are all, in fact, based upon earlier misapprehensions by planetary scientists.

Advances in planetary science in the early years of the Space Age rendered previous notions of the conditions of several locations in the Solar System obsolete.

Similarly, the success of Apollo 11 in 1969 marked the end for stories about fictional first Moon landings.

The planets of the Solar System only appeared sporadically as settings in the 1970s. Extrasolar locations became favoured instead. There was a resurgence towards the end of the century with themes like terraforming.

Games—both video games and tabletop games—use Solar System locations as settings infrequently, and typically as a kind of interchangeable exotic background element.

Planetary tours

Traversing the various worlds of the Solar System, sometimes called a "Grand Tour", is a recurring motif. The first such story was Athanasius Kircher's 1656 work Itinerarium exstaticum, which also engaged in the ongoing cosmological debate between the heliocentric and geocentric model, ultimately endorsing the intermediate Tychonic system. Fontenelle's Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes and Huygen's Cosmotheoros also tour the Solar System in their explorations of the plurality of worlds later in the century, though in both cases the journeys are of the mind rather than of the body.

Fictional components

Various imaginary constituents of the Solar System have appeared in fiction. Outer-space equivalents of the Sargasso Sea appear on occasion.