LIGO

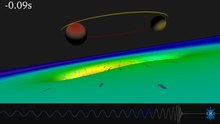

measurement of the gravitational waves at the Livingston (right) and

Hanford (left) detectors, compared with the theoretical predicted values

| |

| Other designations | GW150914 |

|---|---|

| Event type | Gravitational wave event |

| Date | 14 September 2015 |

| Duration | 0.2 second |

| Instrument | LIGO |

| Distance |

410+160 −180 Mpc |

| Redshift |

0.093+0.030 −0.036 |

| Total energy output |

3.0+0.5 −0.5 M☉ × c2 |

| Followed by | GW151226 |

The first direct observation of gravitational waves was made on 14 September 2015 and was announced by the LIGO and Virgo collaborations on 11 February 2016. Previously, gravitational waves had only been inferred indirectly, via their effect on the timing of pulsars in binary star systems. The waveform, detected by both LIGO observatories, matched the predictions of general relativity for a gravitational wave emanating from the inward spiral and merger of a pair of black holes of around 36 and 29 solar masses and the subsequent "ringdown" of the single resulting black hole. The signal was named GW150914 (from "Gravitational Wave" and the date of observation 2015-09-14). It was also the first observation of a binary black hole merger, demonstrating both the existence of binary stellar-mass black hole systems and the fact that such mergers could occur within the current age of the universe.

This first direct observation was reported around the world as a remarkable accomplishment for many reasons. Efforts to directly prove the existence of such waves had been ongoing for over fifty years, and the waves are so minuscule that Albert Einstein himself doubted that they could ever be detected. The waves given off by the cataclysmic merger of GW150914 reached Earth as a ripple in spacetime that changed the length of a 4-km LIGO arm by a thousandth of the width of a proton, proportionally equivalent to changing the distance to the nearest star outside the Solar System by one hair's width. The energy released by the binary as it spiralled together and merged was immense, with the energy of 3.0+0.5

−0.5 c2 solar masses (5.3+0.9

−0.8×1047 joules or 5300+900

−800 foes) in total radiated as gravitational waves, reaching a peak emission rate in its final few milliseconds of about 3.6+0.5

−0.4×1049 watts – a level greater than the combined power of all light radiated by all the stars in the observable universe.

The observation confirms the last remaining directly undetected prediction of general relativity and corroborates its predictions of space-time distortion in the context of large scale cosmic events (known as strong field tests). It was also heralded as inaugurating a new era of gravitational-wave astronomy, which will enable observations of violent astrophysical events that were not previously possible and potentially allow the direct observation of the very earliest history of the universe. The second observation of gravitational waves was made on 26 December 2015 and announced on 15 June 2016. Four more observations were made in 2017, including GW170817, the first observed merger of binary neutron stars, which was also observed in electromagnetic radiation.

Gravitational waves

Play media

Video simulation showing the warping of space-time and gravitational waves produced, during the final inspiral, merge, and ringdown of black hole binary system GW150914.

One case where gravitational waves would be strongest is during the final moments of the merger of two compact objects such as neutron stars or black holes. Over a span of millions of years, binary neutron stars, and binary black holes lose energy, largely through gravitational waves, and as a result, they spiral in towards each other. At the very end of this process, the two objects will reach extreme velocities, and in the final fraction of a second of their merger a substantial amount of their mass would theoretically be converted into gravitational energy, and travel outward as gravitational waves, allowing a greater than usual chance for detection. However, since little was known about the number of compact binaries in the universe and reaching that final stage can be very slow, there was little certainty as to how often such events might happen.

Observation

Play media

Slow

motion computer simulation of the black hole binary system GW150914 as

seen by a nearby observer, during 0.33 s of its final inspiral, merge,

and ringdown. The star field behind the black holes is being heavily

distorted and appears to rotate and move, due to extreme gravitational lensing, as space-time itself is distorted and dragged around by the rotating black holes.

Indirect observation

Evidence of gravitational waves was first deduced in 1974 through the motion of the double neutron star system PSR B1913+16, in which one of the stars is a pulsar that emits electro-magnetic pulses at radio frequencies at precise, regular intervals as it rotates. Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor, who discovered the stars, also showed that over time, the frequency of pulses shortened, and that the stars were gradually spiralling towards each other with an energy loss that agreed closely with the predicted energy that would be radiated by gravitational waves. For this work, Hulse and Taylor were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1993. Further observations of this pulsar and others in multiple systems (such as the double pulsar system PSR J0737-3039) also agree with General Relativity to high precision.Direct observation

Northern arm of the LIGO Hanford Gravitational-wave observatory.

Direct observation of gravitational waves was not possible for the many decades after they were predicted due to the minuscule effect that would need to be detected and separated from the background of vibrations present everywhere on Earth. A technique called interferometry was suggested in the 1960s and eventually technology developed sufficiently for this technique to become feasible.

In the present approach used by LIGO, a laser beam is split and the two halves are recombined after travelling different paths. Changes to the length of the paths or the time taken for the two split beams, caused by the effect of passing gravitational waves, to reach the point where they recombine are revealed as "beats". Such a technique is extremely sensitive to tiny changes in the distance or time taken to traverse the two paths. In theory, an interferometer with arms about 4 km long would be capable of revealing the change of space-time – a tiny fraction of the size of a single proton – as a gravitational wave of sufficient strength passed through Earth from elsewhere. This effect would be perceptible only to other interferometers of a similar size, such as the Virgo, GEO 600 and planned KAGRA and INDIGO detectors. In practice at least two interferometers would be needed, because any gravitational wave would be detected at both of these but other kinds of disturbance would generally not be present at both, allowing the sought-after signal to be distinguished from noise. This project was eventually founded in 1992 as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). The original instruments were upgraded between 2010 and 2015 (to Advanced LIGO), giving an increase of around 10 times their original sensitivity.

LIGO operates two gravitational-wave observatories in unison, located 3,002 km (1,865 mi) apart: the LIGO Livingston Observatory (30°33′46.42″N 90°46′27.27″W) in Livingston, Louisiana, and the LIGO Hanford Observatory, on the DOE Hanford Site (46°27′18.52″N 119°24′27.56″W) near Richland, Washington. The tiny shifts in the length of their arms are continually compared and significant patterns which appear to arise synchronously are followed up to determine whether a gravitational wave may have been detected or if some other cause was responsible.

Initial LIGO operations between 2002 and 2010 did not detect any statistically significant events that could be confirmed as gravitational waves. This was followed by a multi-year shut-down while the detectors were replaced by much improved "Advanced LIGO" versions. In February 2015, the two advanced detectors were brought into engineering mode, in which the instruments are operating fully for the purpose of testing and confirming they are functioning correctly before being used for research, with formal science observations due to begin on 18 September 2015.

Throughout the development and initial observations by LIGO, several "blind injections" of fake gravitational wave signals were introduced to test the ability of the researchers to identify such signals. To protect the efficacy of blind injections, only four LIGO scientists knew when such injections occurred, and that information was revealed only after a signal had been thoroughly analyzed by researchers. On 14 September 2015, while LIGO was running in engineering mode but without any blind data injections, the instrument reported a possible gravitational wave detection. The detected event was given the name GW150914.

GW150914 event

Event detection

GW150914 was detected by the LIGO detectors in Hanford, Washington state, and Livingston, Louisiana, USA, at 09:50:45 UTC on 14 September 2015. The LIGO detectors were operating in "engineering mode", meaning that they were operating fully but had not yet begun a formal "research" phase (which was due to commence three days later on 18 September), so initially there was a question as to whether the signals had been real detections or simulated data for testing purposes before it was ascertained that they were not tests.The chirp signal lasted over 0.2 seconds, and increased in frequency and amplitude in about 8 cycles from 35 Hz to 250 Hz. The signal is in the audible range and has been described as resembling the "chirp" of a bird; astrophysicists and other interested parties the world over excitedly responded by imitating the signal on social media upon the announcement of the discovery. (The frequency increases because each orbit is noticeably faster than the one before during the final moments before merging.)

The trigger that indicated a possible detection was reported within three minutes of acquisition of the signal, using rapid ('online') search methods that provide a quick, initial analysis of the data from the detectors. After the initial automatic alert at 09:54 UTC, a sequence of internal emails confirmed that no scheduled or unscheduled injections had been made, and that the data looked clean. After this, the rest of the collaborating team was quickly made aware of the tentative detection and its parameters.

More detailed statistical analysis of the signal, and of 16 days of surrounding data from 12 September to 20 October 2015, identified GW150914 as a real event, with an estimated significance of at least 5.1 sigma or a confidence level of 99.99994%. Corresponding wave peaks were seen at Livingston seven milliseconds before they arrived at Hanford. Gravitational waves propagate at the speed of light, and the disparity is consistent with the light travel time between the two sites. The waves had traveled at the speed of light for more than a billion years.

At the time of the event, the Virgo gravitational wave detector (near Pisa, Italy) was offline and undergoing an upgrade; had it been online it would likely have been sensitive enough to also detect the signal, which would have greatly improved the positioning of the event. GEO600 (near Hannover, Germany) was not sensitive enough to detect the signal. Consequently, neither of those detectors was able to confirm the signal measured by the LIGO detectors.

Astrophysical origin

Simulation of merging black holes radiating gravitational waves

−180 megaparsecs (determined by the amplitude of the signal), or 1.4±0.6 billion light years, corresponding to a cosmological redshift of 0.093+0.030

−0.036 (90% credible intervals). Analysis of the signal along with the inferred redshift suggested that it was produced by the merger of two black holes with masses of 35+5

−3 times and 30+3

−4 times the mass of the Sun (in the source frame), resulting in a post-merger black hole of 62+4

−3 solar masses. The mass–energy of the missing 3.0±0.5 solar masses was radiated away in the form of gravitational waves.

During the final 20 milliseconds of the merger, the power of the radiated gravitational waves peaked at about 3.6×1049 watts or 526 dBm – 50 times greater than the combined power of all light radiated by all the stars in the observable universe.

Across the 0.2-second duration of the detectable signal, the relative tangential (orbiting) velocity of the black holes increased from 30% to 60% of the speed of light. The orbital frequency of 75 Hz (half the gravitational wave frequency) means that the objects were orbiting each other at a distance of only 350 km by the time they merged. The phase changes to the signal's polarization allowed calculation of the objects' orbital frequency, and taken together with the amplitude and pattern of the signal, allowed calculation of their masses and therefore their extreme final velocities and orbital separation (distance apart) when they merged. That information showed that the objects had to be black holes, as any other kind of known objects with these masses would have been physically larger and therefore merged before that point, or would not have reached such velocities in such a small orbit. The highest observed neutron star mass is two solar masses, with a conservative upper limit for the mass of a stable neutron star of three solar masses, so that a pair of neutron stars would not have had sufficient mass to account for the merger (unless exotic alternatives exist, for example, boson stars), while a black hole-neutron star pair would have merged sooner, resulting in a final orbital frequency that was not so high.

The decay of the waveform after it peaked was consistent with the damped oscillations of a black hole as it relaxed to a final merged configuration. Although the inspiral motion of compact binaries can be described well from post-Newtonian calculations, the strong gravitational field merger stage can only be solved in full generality by large-scale numerical relativity simulations.

In the improved model and analysis, the post-merger object is found to be a rotating Kerr black hole with a spin parameter of 0.68+0.05

−0.06, i.e. one with 2/3 of the maximum possible angular momentum for its mass.

The two stars which formed the two black holes were likely formed about 2 billion years after the Big Bang with masses of between 40 and 100 times the mass of the Sun.

Location in the sky

Gravitational wave instruments are whole-sky monitors with little ability to resolve signals spatially. A network of such instruments is needed to locate the source in the sky through triangulation. With only the two LIGO instruments in observational mode, GW150914's source location could only be confined to an arc on the sky. This was done via analysis of the 6.9+0.5−0.4 ms time-delay, along with amplitude and phase consistency across both detectors. This analysis produced a credible region of 150 deg2 with a probability of 50% or 610 deg2 with a probability of 90% located mainly in the Southern Celestial Hemisphere, in the rough direction of (but much farther than) the Magellanic Clouds.

For comparison, the area of the constellation Orion is 594 deg2.

Coincident gamma-ray observation

The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope reported that its Gamma-Ray Burst Monitor (GBM) instrument detected a weak gamma-ray burst above 50 keV, starting 0.4 seconds after the LIGO event and with a positional uncertainty region overlapping that of the LIGO observation. The Fermi team calculated the odds of such an event being the result of a coincidence or noise at 0.22%. However a gamma ray burst would not have been expected, and observations from the INTEGRAL telescope's all-sky SPI-ACS instrument indicated that any energy emission in gamma-rays and hard X-rays from the event was less than one millionth of the energy emitted as gravitational waves, which "excludes the possibility that the event is associated with substantial gamma-ray radiation, directed towards the observer." If the signal observed by the Fermi GBM was genuinely astrophysical, INTEGRAL would have indicated a clear detection at a significance of 15 sigma above background radiation. The AGILE space telescope also did not detect a gamma-ray counterpart of the event.A follow-up analysis by an independent group, released in June 2016, developed a different statistical approach to estimate the spectrum of the gamma-ray transient. It concluded that Fermi GBM's data did not show evidence of a gamma ray burst, and was either background radiation or an Earth albedo transient on a 1-second timescale. A rebuttal of this follow-up analysis, however, pointed out that the independent group misrepresented the analysis of the original Fermi GBM Team paper and therefore misconstrued the results of the original analysis. The rebuttal reaffirmed that the false coincidence probability is calculated empirically and is not refuted by the independent analysis.

Black hole mergers of the type thought to have produced the gravitational wave event are not expected to produce gamma-ray bursts, as stellar-mass black hole binaries are not expected to have large amounts of orbiting matter. Avi Loeb has theorised that if a massive star is rapidly rotating, the centrifugal force produced during its collapse will lead to the formation of a rotating bar that breaks into two dense clumps of matter with a dumbbell configuration that becomes a black hole binary, and at the end of the star's collapse it triggers a gamma-ray burst. Loeb suggests that the 0.4 second delay is the time it took the gamma-ray burst to cross the star, relative to the gravitational waves.

Other follow-up observations

The reconstructed source area was targeted by follow-up observations covering radio, optical, near infra-red, X-ray, and gamma-ray wavelengths along with searches for coincident neutrinos. However, because LIGO had not yet started its science run, notice to other telescopes was delayed.The ANTARES telescope detected no neutrino candidates within ±500 seconds of GW150914. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory detected three neutrino candidates within ±500 seconds of GW150914. One event was found in the southern sky and two in the northern sky. This was consistent with the expectation of background detection levels. None of the candidates were compatible with the 90% confidence area of the merger event. Although no neutrinos were detected, the lack of such observations provided a limit on neutrino emission from this type of gravitational wave event.

Observations by the Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Mission of nearby galaxies in the region of the detection, two days after the event, did not detect any new X-ray, optical or ultraviolet sources.

Announcement

GW150914 announcement paper –

click to access

The announcement of the detection was made on 11 February 2016 at a news conference in Washington, D.C. by David Reitze, the executive director of LIGO, with a panel comprising Gabriela González, Rainer Weiss and Kip Thorne, of LIGO, and France A. Córdova, the director of NSF. Barry Barish delivered the first presentation on this discovery to a scientific audience simultaneously with the public announcement.

The initial announcement paper was published during the news conference in Physical Review Letters, with further papers either published shortly afterwards or immediately available in preprint form.

Awards and recognition

In May 2016, the full collaboration, and in particular Ronald Drever, Kip Thorne, and Rainer Weiss, received the Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics for the observation of gravitational waves. Drever, Thorne, Weiss, and the LIGO discovery team also received the Gruber Prize in Cosmology. Drever, Thorne, and Weiss were also awarded the 2016 Shaw Prize in Astronomy and the 2016 Kavli Prize in Astrophysics. Barish was awarded the 2016 Enrico Fermi Prize from the Italian Physical Society (Società Italiana di Fisica). In January 2017, LIGO spokesperson Gabriela González and the LIGO team were awarded the 2017 Bruno Rossi Prize.The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Rainer Weiss, Barry Barish and Kip Thorne "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves".

Implications

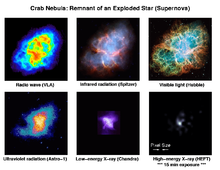

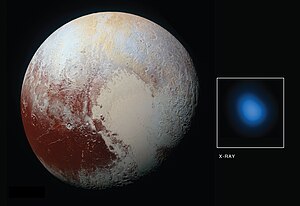

The observation was heralded as inaugurating a revolutionary era of gravitational-wave astronomy. Prior to this detection, astrophysicists and cosmologists were able to make observations based upon electromagnetic radiation (including visible light, X-rays, microwave, radio waves, gamma rays) and particle-like entities (cosmic rays, stellar winds, neutrinos, and so on). These have significant limitations - light and other radiation may not be emitted by many kinds of objects, and can also be obscured or hidden behind other objects. Objects such as galaxies and nebulae can also absorb, re-emit, or modify light generated within or behind them, and compact stars or exotic stars may contain material which is dark and radio silent, and as a result there is little evidence of their presence other than through their gravitational interactions.Expectations for detection of future binary merger events

On 15 June 2016, the LIGO group announced an observation of another gravitational wave signal, named GW151226. The Advanced LIGO is predicted to detect five more black hole mergers like GW150914 in its next observing campaign, and then 40 binary star mergers each year, in addition to an unknown number of more exotic gravitational wave sources, some of which may not be anticipated by current theory.Planned upgrades are expected to double the signal-to-noise ratio, expanding the volume of space in which events like GW150914 can be detected by a factor of ten. Additionally, Advanced Virgo, KAGRA, and a possible third LIGO detector in India will extend the network and significantly improve the position reconstruction and parameter estimation of sources.

Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) is a proposed space based observation mission to detect gravitational waves. With the proposed sensitivity range of LISA, merging binaries like GW150914 would be detectable about 1000 years before they merge, providing for a class of previously unknown sources for this observatory if they exist within about 10 megaparsecs. LISA Pathfinder, LISA's technology development mission, was launched in December 2015 and it demonstrated that the LISA mission is feasible.

A current model predicts LIGO will detect approximately 1000 black hole mergers per year after it reaches full sensitivity planned for 2020.

Lessons for stellar evolution and astrophysics

The masses of the two pre-merger black holes provide information about stellar evolution. Both black holes were more massive than previously discovered stellar-mass black holes, which were inferred from X-ray binary observations. This implies that the stellar winds from their progenitor stars must have been relatively weak, and therefore that the metallicity (mass fraction of chemical elements heavier than hydrogen and helium) must have been less than about half the solar value.The fact that the pre-merger black holes were present in a binary star system, as well as the fact that the system was compact enough to merge within the age of the universe, constrains either binary star evolution or dynamical formation scenarios, depending on how the black hole binary was formed. A significant number of black holes must receive low natal kicks (the velocity a black hole gains at its formation in a core-collapse supernova event), otherwise the black hole forming in a binary star system would be ejected and an event like GW would be prevented. The survival of such binaries, through common envelope phases of high rotation in massive progenitor stars, may be necessary for their survival. The majority of the latest black hole model predictions comply with these added constraints.

The discovery of the GW merger event increases the lower limit on the rate of such events, and rules out certain theoretical models that predicted very low rates of less than 1 Gpc−3yr−1 (one event per cubic gigaparsec per year). Analysis resulted in lowering the previous upper limit rate on events like GW150914 from ~140 Gpc−3yr−1 to 17+39

−13 Gpc−3yr−1.

Impact on future cosmological observation

Measurement of the waveform and amplitude of the gravitational waves from a black hole merger event makes accurate determination of its distance possible. The accumulation of black hole merger data from cosmologically distant events may help to create more precise models of the history of the expansion of the universe and the nature of the dark energy that influences it.The earliest universe is opaque since the cosmos was so energetic then that most matter was ionized and photons were scattered by free electrons. However, this opacity would not affect gravitational waves from that time, so if they occurred at levels strong enough to be detected at this distance, it would allow a window to observe the cosmos beyond the current visible universe. Gravitational-wave astronomy therefore may some day allow direct observation of the earliest history of the universe.

Tests of general relativity

The inferred fundamental properties, mass and spin, of the post-merger black hole were consistent with those of the two pre-merger black holes, following the predictions of general relativity. This is the first test of general relativity in the very strong-field regime. No evidence could be established against the predictions of general relativity.The opportunity was limited in this signal to investigate the more complex general relativity interactions, such as tails produced by interactions between the gravitational wave and curved space-time background. Although a moderately strong signal, it is much smaller than that produced by binary-pulsar systems. In the future stronger signals, in conjunction with more sensitive detectors, could be used to explore the intricate interactions of gravitational waves as well as to improve the constraints on deviations from general relativity.