From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Comrade Lenin Cleanses Earth of Filth" by

Viktor Deni, November 1920

Propaganda in the Soviet Union was the practice of state-directed communication to promote class conflict, internationalism, the goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the party itself.

The main Soviet censorship body, Glavlit,

was employed not only to eliminate any undesirable printed materials

but also "to ensure that the correct ideological spin was put on every

published item." Under Stalinism,

deviation from the dictates of official propaganda was punished by

execution and labor camps. Afterwards, such punitive measures were

replaced by punitive psychiatry,

prison, denial of work, and loss of citizenship. "Today a man only

talks freely to his wife – at night, with the blankets pulled over his

head," the writer Isaac Babel privately told a trusted friend.

Theory of propaganda

According to historian Peter Kenez, "the Russian socialists have contributed nothing to the theoretical discussion of the techniques of mass persuasion. ... The Bolsheviks

never looked for and did not find devilishly clever methods to

influence people's minds, to brainwash them." Kenez says this lack of

interest "followed from their notion of propaganda. They thought of

propaganda as part of education."

In a study published in 1958, business administration professor Raymond

Bauer concluded: "Ironically, psychology and the other social sciences

have been employed least in the Soviet Union for precisely those

purposes for which Americans popularly think psychology would be used in

a totalitarian state—political propaganda and the control of human

behavior."

Media

Schools and youth organizations

Young Pioneers, with their slogan: "Prepare to fight for the cause of the Communist Party"

An important goal of Soviet propaganda was to create a New Soviet man. Schools and Communist youth organizations such as the Young Pioneers and Komsomol served to remove children from the "petit-bourgeois" family and indoctrinate the next generation into the "collective way of life". The idea that the upbringing of children was the concern of their parents was explicitly rejected.

One schooling theorist stated:

We must make the young into a

generation of Communists. Children, like soft wax, are very malleable

and they should be moulded into good Communists... We must rescue

children from the harmful influence of the family... We must nationalize

them. From the earliest days of their little lives, they must find

themselves under the beneficent influence of Communist schools... To

oblige the mother to give her child to the Soviet state – that is our

task.

Those born after the Russian Revolution

were explicitly told that they were to build a utopia of brotherhood

and justice, and to not be like their parents, but completely Red.

"Lenin's corners", "political shrines for the display of propaganda

about the god-like founder of the Soviet state", were established in all

schools.

Schools conducted marches, songs, and pledges of allegiance to Soviet

leadership. One of the purposes was to instill in children the idea

that they are involved in the world revolution, which is more important than any family ties. Pavlik Morozov, who denounced his father to the secret police NKVD, was promoted as a great positive example.

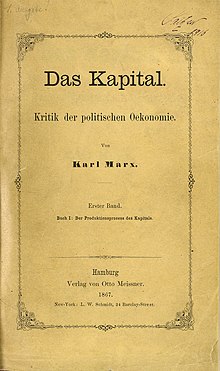

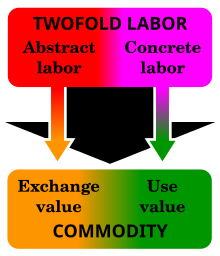

Teachers in economic and social sciences were particularly responsible for inculcating "unshakable" Marxist–Leninist views.

All teachers were prone to strictly follow the plan for educating

children approved by the top for reasons of safety, which could cause

serious problems dealing with social events that, having just happened,

were not included in the plan. Children of "socially alien" elements were often the target of abuse or expelled, in the name of class struggle.

Early in the regime, many teachers were drawn into Soviet plans for

schooling because of a passion for literacy and numeracy, which the

Soviets were attempting to spread.

The Young Pioneers were an important factor in the indoctrination of children. They were taught to be truthful and uncompromising and to fight the enemies of socialism. By the 1930s, this indoctrination completely dominated the Young Pioneers.

Radio

The radio was put to good use, especially to reach the illiterate; radio receivers were put in communal locations, where the peasants would have to come to hear the news, such as changes to rationing, and received propaganda broadcasts with it; some of these locations were also used for posters.

During World War II, radio was used to propagandize Germany; German POWs

would be brought on to speak and assure their relatives they were

alive, with propaganda being inserted between the announcement that a

soldier would speak and when he actually did, in the time allowed for

his family to gather.

Posters

"To have more, we must produce more. To produce more, we must know more"

Wall posters were widely used in the early days, often depicting the Red Army's triumphs for the benefit of the illiterate. Throughout the 1920s, this was continued.

This continued in World War II, still for the benefit of the less literate, with bold, simple designs.

Cinema

Films were heavily propagandist, although they were pioneers in the documentary field (Roman Karmen, Dziga Vertov). When war appeared inevitable, dramas, such as Alexander Nevsky (1938) were written to prepare the population; these were withdrawn after the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, but returned to circulation after the war began.

Films were shown in theaters and from propaganda trains. During the war newsreels were shown in subway stations so that the poor were not excluded by an inability to pay. Films were also shot with stories of partisan activity, and of the suffering inflicted by the Nazis, such as Girl No. 217, depicting a Russian girl enslaved by an inhuman German family.

Because film needs an industrial base, propaganda also made much of the output of film.

Propaganda train

An institution during World War II was the propaganda train, fitted with presses and portable cinemas, staffed with lecturers. In the Civil War the Soviets sent out both "agitation trains" (Russian: агитпоезд) and "agitation steamboats [ru]" (Russian: агитпароход) to inform, entertain, and propagandize.

Meetings and lectures

Meetings

with speakers were also used. Despite their dullness, many people

found they created solidarity, and made them feel important and that

they were being kept up to date on news.

Lectures were habitually used to instruct in the proper way of every corner of life.

Joseph Stalin's lectures on Leninism were instrumental in establishing that the Party was the cornerstone of the October Revolution, a policy Lenin acted on but did not write of theoretically.

Art

Worker and Kolkhoz Woman commemorated in a stamp

Art, whether literature, visual art, or performing art, was used for the purpose of propaganda. Furthermore, it should show one clear and unambiguous meaning.

Long before Stalin imposed complete restraint, a cultural bureaucracy

was growing up that regarded art's highest form and purpose as

propaganda and began to restrain it to fit that role. Cultural activities were constrained by censorship and a monopoly of cultural institutions.

Imagery frequently drew on heroic realism. The Soviet pavilion for the Paris World Fair was surmounted by Vera Mukhina's a monumental sculpture, Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, in heroic mold. This reflected a call for heroic and romantic art, which reflected the ideal rather than the realistic.

Art was filled with health and happiness; paintings teemed with busy

industrial and agricultural scenes, and sculptures depicted workers,

sentries, and schoolchildren.

In 1937, the Industry of Socialism was intended as a major

exhibit of socialist art, but difficulties with pain and the problem of "enemies of the people" appearing in scene required reworking, and sixteen months later, the censors finally approved enough for an exhibition.

Newspapers

In 1917, coming out of underground movements, the Soviets prepared to begin publishing Pravda.

The very first law the Soviets passed on assuming power was to suppress newspapers that opposed them. This had to be repealed and replaced with a milder measure, but by 1918, Lenin had liquidated the independent press, including journals stemming from the 18th century.

From 1930 to 1941, as well as briefly in 1949, the propaganda journal USSR in Construction was circulated. It was published in Russian, French, English, German, and, from 1938, Spanish.

The self-proclaimed purpose of the magazine was to "reflect in

photography the whole scope and variety of the construction work now

going on the USSR".

The issues were aimed primarily at an international audience,

especially Western left-wing intellectuals and businessmen, and were

quite popular during its early publications, with subscribers including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, John Galsworthy, and Romain Rolland.

Illiteracy was regarded as a grave danger, excluding the illiterate from political discussion. In part this was because the people could not be reached by Party journals.

Books

Immediately after the revolution, books were treated with less severity than newspapers, but the nationalizing of printing presses and publishing houses brought them under control. In the Stalinist era, libraries were purged, sometimes so extremely that works by Lenin were removed.

In 1922, the deportation of writers and scholars warned that no

deviation was permitted, and pre-publication censorship was reinstated.

Due to a lack of Bolshevist authors, many "fellow travelers" were

tolerated, but money only came as long as they toed the party line.

During the Stalinist Great Purges, textbooks were often so frequently revised that students had to do without them.

Theatre

The revolutionary theater was used to inspire support for the regime and hatred of its enemies, particularly agitprop theater, noted for its cardboard characters of perfect virtue and complete evil, and its coarse ridicule. Petrushka was a popular figure, often used to defend rich peasants and attack kulaks.

Themes

New man

Many Soviet works depicted the development of a "positive hero" as requiring intellectualism and hard discipline. He was not driven by crude impulses of nature but by conscious self-mastery.

The selfless new man was willing to sacrifice not only his life but

his self-respect and his sensitivity for the good of others. Equality and sacrifice were touted as the ideal appropriate for the "socialist way of life."

Work required exertion and austerity, to show the new man triumphing over his base instincts. Alexey Stakhanov's record-breaking day in mining coal caused him to be set forth as the exemplar of the "new man" and to inspire Stakhanovite movements. The movement inspired much pressure to increase production, on both workers and managers, with critics labeled "wreckers".

This reflected a change from early days, with emphasis on the

"little man" among the anonymous labors, to favoring the "hero of labor"

in the end of the First Five-Year Plan, with writers explicitly told to produce heroization. While these heroes had to stem from the people, they were set apart by their heroic deeds.

Stakhanov himself was well suited for this role, not only a worker but

for his good looks like many poster hero and as a family man. The hardships of the First Five-Year Plan were put forth in romanticized accounts. In 1937–38, young heroes who accomplished great feats appeared on the front page of Pravda more often than Stalin himself.

Later, during the purges, claims were made that criminals had been "reforged" by their work on the White Sea/Baltic Canal; salvation through labor appeared in Nikolai Pogodin's The Aristocrats as well as many articles.

This could also be a new woman; Pravda described the Soviet woman as someone who had and could never have existed before. Female Stakhanovites were rarer than male, but a quarter of all trade-union women were designated as "norm-breaking." For the Paris World Fair, Vera Mukhina depicted a monumental sculpture, Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, dressed in work clothing, pressing forward with his hammer and her sickle crossed.

Pro-natalist policies encouraging women to have many children were

justified by the selfishness inherent in limiting the next generation of

"new men." "Mother-heroines" received medals for ten or more children.

Stakhanovites were also used as propaganda figures so heavily that some workers complained that they were skipping work.

The murder of Pavlik Morozov was widely exploited in propaganda to urge on children the duty of informing on even their parents to the new state.

Class enemy

The class enemy was a pervasive feature of Soviet propaganda. With the Civil War, the newly formed army moved to massacre large numbers of kulaks and otherwise promulgate a short lived "reign of terror" to terrify the masses into obedience.

Lenin proclaimed that they were exterminating the bourgeoisie

as a class, a position reinforced by the many actions against

landlords, well-off peasants, banks, factories, and private shops.

Stalin warned, often, that with the struggle to build a socialist

society, the class struggle would sharpen as class enemies grew more

desperate. During the Stalinist era, all opposition leaders were routinely described as traitors and agents of foreign, imperialist powers.

The Five-Year Plan intensified the class struggle with many attacks on kulaks, and when it was found that many peasant opponents were not rich enough to qualify, they were declared "sub-kulaks." "Kulaks and other class-alien enemies" were often cited as the reason for failures on collective farms.

Throughout the First and Second Five-Year Plans, kulaks, wreckers,

saboteurs and nationalists were attacked, leading up to the Great Terror. Those who profited from public property were "enemies of the people." By the late 1930s, all "enemies" were lumped together in art as supporters of historical idiocy. Newspapers reported even on the trial of children as young as ten for counterrevolutionary and fascist behavior. During the Holodomor,

the starving peasants were denounced as saboteurs, all the more

dangerous in that their gentle and inoffensive appearance made them

appear innocent; the deaths were only proof that peasants hated

socialism so much they were willing to sacrifice their families and risk

their lives to fight it.

Stalin, denouncing White counter-revolutionaries, Trotskyists, wreckers, and others, particularly aimed his attention at the Communist old guard. The very improbability of the charges was cited as evidence, since more plausible charges could have been invented.

These enemies were rounded up for the gulags, which propaganda proclaimed to be "corrective labor camps" to such an extent that even people who saw the starvation and slave labor believed the propaganda rather than their eyes.

During World War II, entire nationalities, such as the Volga Germans, were branded traitors.

Stalin himself informed Sergei Eisenstein that his film Ivan the Terrible was flawed because it did not show the necessity of terror in Ivan's persecution of the nobility.

New society

Propaganda

can start a large movement or revolution, but only if the masses rally

behind one another to make the images produced by propaganda a reality.

Good propaganda must instill hope, faith, and certainty. It must bring

solidarity among the population. It must stave off demoralization,

hopelessness, and resignation.

A common theme was the creation of a new, utopian society,

depicted in posters and newsreels, which inspired an enthusiasm in many

people. Much propaganda was dedicated to a new community, as exemplified in the use of "comrade." This new society was to be classless. Distinctions were to be based on function, not class, and all possessed the equal duty to work. During the 1930s discussion of the new constitution, one speaker proclaimed that there were, in fact, no classes in the USSR, and newspapers effused over how the dreams of the working class were coming true for the luckiest people in the world. One admission that there were classes – workers, peasants, and working intelligentsia – dismissed it as unimportant, as these new classes had no need to conflict.

Military metaphors were used frequently for this creation, as in

1929, where the collectivization of agriculture was officially termed a

"full-scale socialist offensive on all fronts."

The Second Five-Year Plan saw a slowdown of the Socialist Offensive,

this against a propaganda background of trumpeting the USSR's triumphs

on "the battlefield of building socialism."

In Stalinist times, this was often portrayed as a "great family", with Stalin as the great father.

Happiness was mandatory; in a novel where a horse was described

as moving "slowly", the censor objected, asking why it was not moving

speedily, being happy like the rest of the collective farm workers.

Kohlkhoznye Rebiata published bombastic reports from the collective farms of their children.

When hot breakfasts were provided for schoolchildren, particularly in

city schools, the program was announced with great fanfare.

Since communist society was the highest and most progressive form

of society, it was ethically superior to all others, and "moral" and

"immoral" were determined by whether things helped or hindered its

development. Tsarist law was overtly abolished, and while judges could use it, they were to be guided by "revolutionary consciousness".

Under the pressure of the need for law, more and more was implemented;

Stalin justified this in propaganda as the law would "wither away" best

when its authority was raised to the highest, through its

contradictions.

When the draft of the new constitution led people to believe that

private property would be returned and that workers could leave collective farms, speakers were sent out to "clarify" the matter.

Production

Stalin bluntly declared the Bolshevists must close the Tsar-induced fifty- or a hundred-year gap with Western countries in ten years, or "socialism would be destroyed". In support of the Five-Year Plan, he declared being an industrial laggard had caused Russia's historical defeats. Newspapers reported overproduction of quotas, even though many had not occurred, and where they did, the goods were often shoddy.

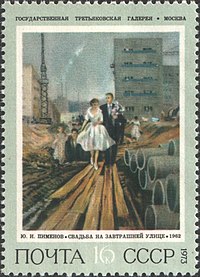

A stamp featuring Pimenov's "Wedding on a Tomorrow Street"

During the 1930s, the development of the USSR was just about the only theme of art, literature and film. The heroes of Arctic exploration were glorified.

The twentieth anniversary of the October Revolution was honored with a

five volume work glorifying the accomplishments of socialism and (in

the last volume) "scientifically based fantasies" of the future, raising

such questions as whether the whole world or only Europe would be

socialist in twenty years.

Even while a majority of the population was still rural, the USSR was proclaimed "a mighty industrial power." USSR in Construction glorified the Moscow-Volga Canal, with only the briefest mention of the slave labor that had built it.

In 1939, a rationing plan was considered but not implemented

because it would undermine the propaganda of improving care for the

people, whose lives grew better and more cheerful every year.

During World War II, the slogans were altered from overcoming

backwardness to overcoming the "fascist beast" but continued focus on

production. The slogan proclaimed "Everything for the Front!"

Teams of Young Communists were used as shocktroops to shame workers

into higher production as well as spread socialist propaganda.

In the 1950s, Khrushchev repeatedly boasted that the USSR would soon surpass the West in material well-being.

Other Soviet officials agreed that the USSR would soon show its

superiority because capitalism was like a dead herring – shining as it

rotted.

Subsequently, the USSR was referred to as "developed socialism."

Mass movement

This led to a great emphasis on education.

The first post-mortem attack on Stalin was the publication of articles in Pravda proclaiming that the masses made history and the error of a "cult of the individual."

Peace-loving

A common motif in propaganda was that the Soviet Union was peace-loving.

Many warnings were made of the necessity of keeping out of any

imperialistic war, as the breakdown of capitalism would make capitalist

countries more desperate.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was presented as a peace measure.

Internationalism

Even before the Bolshevists seized power, Lenin proclaimed in

speeches that the Revolution was the vanguard of a worldwide revolution,

both international and socialist.

The workers were informed they were the vanguard of world socialism;

the slogan "Workers of the world, unite!" was constantly repeated.

Lenin founded the organization Comintern to propagate Communism internationally. Stalin proceeded to use it to promote Communism throughout the world for the benefit of the USSR. When this topic was a difficulty dealing with the Allies in World War II, Comintern was dissolved. Similarly, "The Internationale" was dropped as the national anthem in favor of the "Hymn of the Soviet Union".

Japanese prisoners of war were intensively propagandized before their release in 1949, to act as Soviet agents.

Personality cult

While Lenin was uncomfortable with the personality cult that sprung up about him, the party exploited it during the Russian Civil War and officially enshrined it after his death. As early as 1918, a biography of Lenin was written, and busts were produced. With his death, his embalmed body was displayed (to imitate beliefs that the bodies of saints did not decay), and picture books of his life were produced in mass quantities.

Stalin presented himself as a simple man of the people, but distinct from everyday politics by his unique role as leader. His clothing was carefully selected to cement this image. Propaganda presented him as Lenin's heir, exaggerating their relationship, until the Stalin cult

drained out the Lenin cult – an effect shown in posters, where at first

Lenin would be the dominating figure over Stalin, but as time went on

became first only equal, and then smaller and more ghostly, until he was

reduced to the byline on the book Stalin was depicted reading.

This occurred despite the historical accounts describing Stalin as

insignificant, or even a "gray blur", in the early Revolution. From the late 1920s until it was debunked in the 1960s, he was presented as the chief military leader of the civil war. Stalingrad was renamed for him on the claim that he had single-handedly, and against orders, saved it in the civil war.

He often figured as the great father of the "great family" that was the new Soviet Union. Regulations on how exactly to portray Stalin's image and write of his life were carefully promulgated.

Inconvenient facts, such as his having wanted to cooperate with the

Tsarist government on his return for exile, were purged from his

biography.

His work for the Soviet Union was praised in paeans to the "light in the Kremlin window." Marx, Engels, Lenin, and above all Stalin appeared frequently in art.

Discussions of the proposed constitution in the 1930s included effusive thanks to "Comrade Stalin." Engineering projects such as canals were described as having been decreed personally by Stalin. Young Pioneers were enjoined to struggle for "the cause of Lenin and Stalin". During the purges, he increased his appearances in public, having his photograph taken with children, airmen, and Stakhanovites, being hailed as the source of the "happy life," and according to Pravda, riding the subway with common workers.

The propaganda was effectual. Many young people hard at work at construction idolized Stalin.

Many people chose to believe that the charges made at the purges were

true rather than believing that Stalin had betrayed the revolution.

During World War II,

this personality cult was certainly instrumental in inspiring a deep

level of commitment from the masses of the Soviet Union, whether on the

battlefield or in industrial production.

Stalin made a fleeting visit to the front so that propagandists could

claim that he had risked his life with the frontline soldiers. The cult was, however, toned down until approaching victory was near.

As it became clear that the Soviet Union would eventually win the war,

Stalin ensured that propaganda always mentioned his leadership of the

war; the victorious generals were sidelined and never allowed to develop

into political rivals.

Soon after his death, attacks, first veiled and then open, were

made on the "cult of the individual" arguing that history was made by

the masses.

Nikita Khrushchev,

though leading the attacks on the cult, nevertheless sought out

publicity, and his photograph frequently appeared in the newspapers.

Trotsky

As Stalin drew power to himself, Leon Trotsky

was pictured in an anti-personality cult. It began with the assertion

that he had not joined the Bolshevists until late, after the planning of

the October Revolution was done.

Propaganda of extermination

Some historians believe that an important goal of Soviet propaganda was "to justify political repressions of entire social groups which Marxism considered antagonistic to the class of proletariat", as in decossackization or dekulakization campaigns. Richard Pipes wrote: "a major purpose of Soviet propaganda was arousing violent political emotions against the regime's enemies."

The most effective means to achieve this objective "was the denial of the victim's humanity through the process of dehumanization", "the reduction of real or imaginary enemy to a zoological state". In particular, Vladimir Lenin called to exterminate enemies "as harmful insects", "lice" and "bloodsuckers".

According to writer and propagandist Maksim Gorky,

Class hatred should be cultivated by an organic revulsion

as far as the enemy is concerned. Enemies must be seen as inferior. I

believe quite profoundly that the enemy is our inferior, and is a

degenerate not only in the physical plane but also in the moral sense.

According to The Black Book of Communism, an example of demonization of the enemy were speeches by state procurator Andrey Vyshinsky during Stalin's show trials. He said about the suspects:

Shoot these rabid dogs. Death to this gang who hide their

ferocious teeth, their eagle claws, from the people! Down with that

vulture Trotsky,

from whose mouth a bloody venom drips, putrefying the great ideals of

Marxism!... Down with these abject animals! Let's put an end once and

for all to these miserable hybrids of foxes and pigs, these stinking

corpses! Let's exterminate the mad dogs of capitalism,

who want to tear to pieces the flower of our new Soviet nation! Let's

push the bestial hatred they bear our leaders back down their own

throats!

Anti-religious

Early in the revolution, atheistic propaganda was pushed in an attempt to obliterate religion.

Regarding religion more as a class enemy, a cause of hate, than a

contender for people's minds, the government abolished the prerogatives

of the Russian Orthodox Church and targeted them with ridicule.

This included lurid anti-religious processions and newspaper articles

that backfired badly, shocking the deeply religious population. It was stopped and replaced by lectures and other more intellectual methods. The Society of the Godless organized for such purposes, and the magazines Bezbozhnik (The Godless) and The Godless in the Workplace promulgated atheistic propaganda. Atheistic education was regarded as a central task of Soviet schools.

The attempt to liquidate illiteracy was hindered by attempts to combine

it with atheistic education, which caused peasants to stay away and

which was eventually reduced.

In 1929, all forms of religious education were banned as

religious propaganda, and the right to anti-religious propaganda was

explicitly affirmed, whereupon the League of the Godless became the

League of the Militant Godless.

A "Godless Five-Year Plan" was proclaimed, purportedly at the instigation of the masses.

Christian virtues such as humility and meekness were ridiculed in the

press, with self-discipline, loyalty to the party, confidence in the

future, and hatred of class enemies being recommended instead. Anti-religious propaganda in Russia led to a reduction in the public demonstrations of religion.

Much anti-religious efforts were dedicated to promoting science in its place. In the debunking of a miracle – a Madonna weeping tears of blood, which was shown to be rust

contaminating water by pouring multicolored waters into the statue –

was offered to the watching peasants as proof of science, resulting in

the crowd killing two of the scientists.

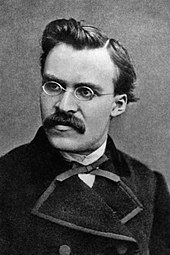

They also tried to overthrow the evangelical image of Jesus. The literature of the USSR in the 1920s, following the tradition of the demythologization of Jesus, created in the works David Strauss, Ernest Renan, Friedrich Nietzsche and Charles Binet-Sanglé, put forward two main themes – Jesus' mental illness and his deception. It was only at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s that the Soviet Union's propaganda won the mythological option, namely the denial of the existence of Jesus.

A "Living Church" movement despised Russian Orthodoxy's hierarchy and preached that socialism was the modern form of Christianity; Trotsky urged their encouragement to split Orthodoxy.

During World War II, this effort was rolled back; Pravda capitalized the word "God" for the first time, as religious attendance was actually encouraged. Much of this was for foreign consumption, where it was widely disbelieved, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt condemning both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union as atheistic regimes which did not permit freedom of conscience. This rollback may have occurred due to the ineffectiveness of the Soviets' anti-religious effort.

Anti-intellectualism

Between

campaigns against bourgeois culture and making the ideology of the

Socialist Offensive intelligible to the masses with cliches and

stereotypes, an anti-intellectual tone grew in propaganda.

Soviet leaders posed as common people, lacking interest in such matters

as fine art and ballet, even as they selectively chose from working class culture.

Plutocracies

In

the 1920s, much Soviet propaganda for the outside world was aimed at

capitalist countries as plutocracies, and claiming that they intended to

destroy the Soviet Union as the workers' paradise. Capitalism, being responsible for the ills of the world, therefore was fundamentally immoral.

Fascism was presented as a terroristic outburst of finance capital, and drawing from the petit bourgeoisie, and the middling peasants, equivalent to kulaks, who were the losers in the historical process.

During the early stages of World War II, it was overtly presented

as a war between capitalists, which would weaken them and allow

Communist triumph as long as the Soviet Union wisely stayed out. Communist parties over the world were instructed to oppose the war as a clash between capitalist states.

After World War II, the United States of America was presented as

a bastion of imperial oppression, with which non-violent competition

would take place, as capitalism was in its last stages.

Anti-Tsarist

Campaigns

against the society of Imperial Russia continued well into the Soviet

Union's history. One speaker recounted how men had had to serve for

twenty-five years in the imperial army, to be heckled by an audience

member that it did not matter, since they had had food and clothing.

Children were informed that the "accursed past" had been left far behind them, they could become completely "Red".

Anti-Polish

Soviet

soldier freeing Ukrainian peasants from Polish lordship, 1939. Note the

Poles were characterised as mustached tormentors in jackboots

Red

Army soldier grabs the knife in the hand of an enemy dwarf in a Polish

uniform, forcing the knife to drop. By Kriukov, Soviet Union, 1939,

Poster collection, Hoover Archives

The Soviet press showed a little favor towards its neighboring states. Poland was a subject of this approach from the very beginning. In general, the Soviet press portrayed Poland as a fascist state, that belonged to the same club as Germany and Italy.

Anti-Polish propaganda was heavily used in the Polish-Soviet War in 1920 as well as during the Soviet invasion of Poland and subsequent annexation of Eastern Poland 1939–1941. (see Fig 1)

Poland's capitalist government and its chief of state, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, were fierce anti-communists; all parties or groups affiliated with Communist activities were banned and its members sent to Bereza Kartuska concentration camp in eastern Poland. This potentially fueled Soviet propaganda against the Polish state and vice versa. The posters often featured capitalist mustached Poles dressed as lords, barons, nobles or generals holding a whip over enslaved Ukrainians and Belarusians, which were a minority in Poland at the time.

Spanish war

Many Soviet and Communist writers and artists participated in the Spanish Civil War (Mikhail Koltsov, Ilya Ehrenburg) or supported the Republicans. Popular revolutionary poem Grenada by Mikhail Arkadyevich Svetlov was published in 1926.

World War II

Pre-war anti-Nazi propaganda

Professor Mamlock and The Oppenheim Family were released in 1938 and 1939 respectively.

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

In the face of massive Soviet bewilderment, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was defended by speaker in Gorky Park. Molotov defended it in an article in Pravda proclaiming that it was a treaty between states, not systems. Stalin himself devised diagrams to show that Neville Chamberlain had wanted to pit the USSR against Nazi Germany, but Comrade Stalin had wisely pit Great Britain against Nazi Germany.

For the duration of the pact, propagandists highly praised Germans. Anti-German or anti-Nazi propaganda like Professor Mamlock were banned.

Anti-German

After the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, Stalin himself declared in a 1941 broadcast that Germany waged war to exterminate the peoples of the USSR. Propaganda published in Pravda denounced all Germans as killers, bloodsuckers, and cannibals, and much play was made of atrocity claims. Hatred was actively and overtly encouraged. They were told that the Germans took no prisoners. Partisans were encouraged to see themselves as avengers. Ilya Ehrenburg was a prominent propaganda writer.

Many anti-German films in the Nazi era revolved about the persecution of Jews in Germany, such as Professor Mamlock (1938) and The Oppenheim Family. Girl No. 217 depicted the horrors inflicted on Soviet POWs, especially the enslavement of the main character Tanya to an inhuman German family, reflecting the harsh treatment of OST-Arbeiter in Nazi Germany.

Despite their own treatment of religion, a revival of Orthodoxy

was permitted during World War II to demonize Nazism as the sole enemy

of religion.

Vasily Grossman and Mikhail Arkadyevich Svetlov were war correspondents of the Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star).

Germany vs. Hitlerites

Soviet

propaganda to Germans during World War II was at pains to distinguish

between the ordinary Germans and their leaders, the Hitlerites (Nazis), and declaring they had no quarrel with the people.

The only way to discover if a German soldier had fallen alive into

Soviet hands was to listen; the radio would announce that a certain

prisoner would speak, then give some time for his family to gather and

listen, and fill it with propaganda.

A National Committee for 'Free Germany' was founded in Soviet

prisoner-of-war camps in an attempt to foment an uprising in Germany.

Anti-fascism

British and Soviet servicemen over body of

swastikaed dragon

Anti-fascism was commonly used in propaganda aimed outside the USSR during the 1930s, particularly to draw people into front organizations. The Spanish Civil War was, in particular, used to quash dissent among European communist parties and reports of Stalin's growing totalitarianism.

Patriotism

In

face of the threat of Nazi Germany, the international claims of

Communism were played down, and people were recruited to help defend the

country on patriotic motives.

The presence of a real enemy was used to inspire action and production

in face of the threat to the Father Soviet Union, or Mother Russia. All Soviet citizens were called on to fight, and soldiers who surrendered had failed in their duty. To prevent retreats from Stalingrad, soldiers were urged to fight for the soil.

Russian history was pressed into providing a heroic past and

patriotic symbols, although selectively, for instance praising men as

state builders. Alexander Nevsky

made a central theme the importance of the common people in saving

Russia while nobles and merchants did nothing, a motif that was heavily

employed. Still, the figures selected had no socialist connection.

Artists and writers were permitted more freedom, as long as they did

not criticize Marxism directly and contained patriotic themes. It was termed the "Great Patriotic War" and stories presented it as a fight of ordinary people's heroism.

While the term motherland was used, it was used to mean the Soviet Union, and while Russian heroes were revived, Soviet heroes were used plentifully as well. Appeals were made that the home of other nationalities were also the homes of their own.

Many Soviet citizens found treatment of soldiers who fell into

enemy hands as "traitors to the Motherland" as suitable for their own

grim determination, and "not a step back" inspired soldiers to fight

with self-sacrifice and heroism.

This continued after the war in a campaign to remove anti-patriotic elements.

In the 1960s, reviving memories of the Great Patriotic War

was used to bolster support for the regime, with all accounts to

carefully censored to prevent accounts of Stalin's early incompetence,

the defeats, and the heavy cost.

Utopia and space

Throughout

the history of the Soviet Union, the concept of a Socialist Utopia was

heavily proselytized by the Soviet government. Under the Khrushchev

administration, this idea of a Soviet utopia was worked heavily into the

concept of space travel and spreading across the world.

The accomplishments in space were closely tied to a sense of utopia and

the idea that communism was superior to other forms of government. In a

press release after Sputnik's launch the Soviet Union states that

"...our contemporaries will witness how the freed and conscientious

labour of the people of the new socialist society makes the most daring

dreams of mankind a reality."

The concept of success in science and space exploration were closely

tied to the concept of a new socialist society and the utopia that would

be created in that society.

Soviet propaganda abroad

World War II propaganda leaflet dropped from a Soviet airplane on Finnish territory, urging Finnish soldiers to surrender

Trotsky and a small group of Communists regarded the Soviet Union as

doomed without the spread of the revolution internationally.

The victory of Stalin, who regarded the construction of socialism in

the Soviet Union as a necessary exemplar to the rest of the world and

represented the majority view, did not, however, stop international propaganda.

In the 1980s, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) estimated that the budget of Soviet propaganda abroad was between $3.5 and $4 billion.

Propaganda abroad was partly conducted by Soviet intelligence agencies. GRU alone spent more than $1 billion for propaganda and peace movements against Vietnam War, which was a "hugely successful campaign and well worth the cost", according to GRU defector Stanislav Lunev. He claimed that "the GRU and the KGB helped to fund just about every antiwar movement and organization in America and abroad".

According to Oleg Kalugin, "the Soviet intelligence was really unparalleled. ... The KGB programs – which would run all sorts of congresses, peace congresses, youth congresses, festivals, women's movements, trade union movements, campaigns against U.S. missiles in Europe, campaigns against neutron weapons, allegations that AIDS ... was invented by the CIA ... all sorts of forgeries and faked material – [were] targeted at politicians, the academic community, at the public at large."

Soviet-run movements pretended to have little or no ties with the

USSR, often seen as noncommunist (or allied to such groups), but were

controlled by the USSR. Most members and supporters, did not realize that they were instruments of Soviet propaganda. The organizations aimed at convincing well-meaning but naive Westerners to support Soviet overt or covert goals.

A witness in a US congressional hearing on Soviet cover activity

described the goals of such organizations as to "spread Soviet

propaganda themes and create false impression of public support for the

foreign policies of Soviet Union."

Much of the activity of the Soviet-run peace movements was supervised by the World Peace Council. Other important front organizations included the World Federation of Trade Unions, the World Federation of Democratic Youth, and the International Union of Students. Somewhat less important front organizations included: Afro-Asian People's Solidarity Organization, Christian Peace Conference, International Association of Democratic Lawyers, International Federation of Resistance Movements, International Institute for Peace, International Organization of Journalists, Women's International Democratic Federation and World Federation of Scientific Workers. There were also numerous smaller organizations, affiliated with the above fronts.

Those organizations received in total more than 100 million dollars from the USSR every year.

Propaganda against the United States and the greater Western world included the following actions: