From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The actions by governments of communist states have been subject to criticism across the political spectrum. Communist party rule has been especially criticized by anti-communists and right-wing critics, but also by other socialists such as anarchists, communists, democratic socialists, libertarian socialists and Marxists. Ruling communist parties have also been challenged by domestic dissent. According to the critics, rule by communist parties has often led to totalitarianism, political repression, restrictions of human rights, poor economic performance, and cultural and artistic censorship.

Several authors noted gaps between official policies of equality

and economic justice and the reality of the emergence of a new class in

communist countries which thrived at the expense of the remaining

population. In Central and Eastern Europe, the works of dissidents Václav Havel and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn gained international prominence, as did the works of disillusioned ex-communists such as Milovan Đilas, who condemned the new class or nomenklatura system that had emerged under communist party rule. Major criticism also comes from the anti-Stalinist left and other socialists. Its socio-economic nature has been much debated, varyingly being labelled a form of bureaucratic collectivism, state capitalism, state socialism, or a totally unique mode of production.

Communist party rule has been criticized as authoritarian or totalitarian for suppressing and killing political dissidents and social classes (so-called "enemies of the people"), religious persecution, ethnic cleansing, forced collectivization, and use of forced labor in concentration camps. Communist party rule has also been accused of genocidal acts in Cambodia, China, Poland and Ukraine, although there is scholarly dispute regarding the Holodomor's classification as genocide. Western criticism of communist rule has also been grounded in criticism of socialism by economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, who argued that the state ownership and planned economy characteristic of Soviet-style communist rule were responsible for economic stagnation and shortage economies, providing few incentives for individuals to improve productivity and engage in entrepreneurship. Anti-Stalinist left and other left-wing critics see it as an example of state capitalism and have referred to it as a "red fascism" contrary to left-wing politics. Other leftists, including Marxist–Leninists, criticize it for its repressive state actions while recognizing certain advancements such as egalitarian achievements and modernization under such states.

Counter-criticism is diverse, including the view it presents a biased

or exaggerated anti-communist narrative. Some academics propose a more

nuanced analysis of communist party rule.

Excess deaths under communist party rule have been discussed as part of a critical analysis of communist party rule. According to Klas-Göran Karlsson, discussion of the number of victims of communist party rule has been "extremely extensive and ideologically biased." Any attempt to estimate a total number of killings under communist party rule depends greatly on definitions, ranging from a low of 10–20 million to as high as 148 million. The criticism of some of the estimates are mostly focused on three

aspects, namely that (i) the estimates are based on sparse and

incomplete data when significant errors are inevitable; (ii) the figures

are skewed to higher possible values; and (iii) those dying at war and

victims of civil wars, Holodomor and other famines under communist party rule should not be counted.

Others have argued that, while certain estimates may not be accurate,

"quibbling about numbers is unseemly. What matters is that many, many

people were killed by communist regimes." Right-wing commentators argue that these excess deaths and killings are an indictment of communism,

while opponents of this view, including members of the political left,

argue that these killings were aberrations caused by specific

authoritarian regimes instead of communism, and point to mass deaths

that they claim were caused by capitalism and anti-communism as a counterpoint to communist killings.

Background and overview

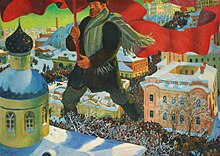

After the Russian Revolution, communist party rule was consolidated for the first time in Soviet Russia

(later the largest constituent republic of the Soviet Union, formed in

December 1922) and criticized immediately domestically and

internationally. During the first Red Scare in the United States, the takeover of Russia by the communist Bolsheviks was considered by many a threat to free markets, religious freedom and liberal democracy. Meanwhile, under the tutelage of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the only party permitted by the Soviet Union constitution, state institutions were intimately entwined with those of the party. By the late 1920s, Joseph Stalin consolidated the regime's control over the country's economy and society through a system of economic planning and five-year plans.

Between the Russian Revolution and the Second World War,

Soviet-style communist rule only spread to one state that was not later

incorporated into the Soviet Union. In 1924, communist rule was

established in neighboring Mongolia, a traditional outpost of Russian

influence bordering the Siberian region. However, throughout much of

Europe and the Americas criticism of the domestic and foreign policies

of the Soviet regime among anticommunists continued unabated. After the end of World War II, the Soviet Union took control over the territories reached by the Red Army, establishing what later became known as the Eastern Bloc. Following the Chinese Revolution, the People's Republic of China was proclaimed in 1949 under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.

Between the Chinese Revolution and the last quarter of the 20th

century, communist rule spread throughout East Asia and much of the Third World and new communist regimes

became the subject of extensive local and international criticism.

Criticism of the Soviet Union and Third World communist regimes have

been strongly anchored in scholarship on totalitarianism which asserts that communist parties maintain themselves in power without the consent of the governed and rule by means of political repression, secret police, propaganda disseminated through the state-controlled mass media, repression of free discussion and criticism, mass surveillance and state terror. These studies of totalitarianism influenced Western historiography on communism and Soviet history, particularly the work of Robert Conquest and Richard Pipes on Stalinism, the Great Purge, the Gulag and the Soviet famine of 1932–1933.

Areas of criticism

Criticism of communist regimes has centered on many topics, including their effects on the economic development, human rights, foreign policy, scientific progress and environmental degradation of the countries they rule.

Political repression is a topic in many influential works critical of communist rule, including Robert Conquest's accounts of Stalin's Great Purge in The Great Terror and the Soviet famine of 1932–33 in The Harvest of Sorrow; Richard Pipes' account of the "Red Terror" during the Russian Civil War; Rudolph Rummel's work on "democide"; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's account of Stalin's forced labor camps in The Gulag Archipelago; and Stéphane Courtois'

account of executions, forced labor camps and mass starvation in

communist regimes as a general category, with particular attention to

the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin and China under Mao Zedong.

Soviet-style central planning and state ownership has been

another topic of criticism of communist rule. Works by economists such

as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman

argue that the economic structures associated with communist rule

resulted in economic stagnation. Other topics of criticism of communist

rule include foreign policies of expansionism, environmental degradation

and the suppression of free cultural expression.

Artistic, scientific and technological policies

Criticism

of communist rule has also centered on the censorship of the arts. In

the case of the Soviet Union, these criticisms often deal with the

preferential treatment afforded to socialist realism.

Other criticisms center on the large-scale cultural experiments of

certain communist regimes. In Romania, the historical center of

Bucharest was demolished and the whole city was redesigned between 1977

and 1989. In the Soviet Union, hundreds of churches were demolished or

converted to secular purposes during the 1920s and 1930s. In China, the Cultural Revolution sought to give all artistic expression a 'proletarian' content and destroyed much older material lacking this.

Advocates of these policies promised to create a new culture that would

be superior to the old while critics argue that such policies

represented an unjustifiable destruction of the cultural heritage of

humanity.

There is a well-known literature focusing on the role of the falsification of images in the Soviet Union under Stalin. In The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs in Stalin's Russia, David King

writes: "So much falsification took place during the Stalin years that

it is possible to tell the story of the Soviet era through retouched

photographs".

Under Stalin, historical documents were often the subject of

revisionism and forgery, intended to change public perception of certain

important people and events. The pivotal role played by Leon Trotsky

in the Russian Revolution and Civil War was almost entirely erased from

official historical records after Trotsky became the leader of a

Communist faction that opposed Stalin's rule.

The emphasis on the "hard sciences" of the Soviet Union has been criticized. There were very few Nobel Prize winners from Communist states. Soviet research in certain sciences was at times guided by political rather than scientific considerations. Lysenkoism and Japhetic theory were promoted for brief periods of time in biology and linguistics respectively, despite having no scientific merit. Research into genetics was restricted because Nazi use of eugenics had prompted the Soviet Union to label genetics a "fascist science". Suppressed research in the Soviet Union also included cybernetics, psychology, psychiatry and organic chemistry.

Soviet technology in many sectors lagged Western technology. Exceptions include areas like the Soviet space program

and military technology where occasionally Communist technology was

more advanced due to a massive concentration of research resources.

According to the Central Intelligence Agency,

much of the technology in the Communist states consisted simply of

copies of Western products that had been legally purchased or gained

through a massive espionage program. Some even say that stricter Western

control of the export of technology through the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls and providing defective technology to Communist agents after the discovery of the Farewell Dossier contributed to the fall of Communism.

Economic policy

Estimates of national income (GNP) growth per year in the Soviet Union, 1928–1985

|

Khanin |

Bergson/CIA |

TsSu

|

| 1928–1980 |

3.3 |

4.3 |

8.8

|

| 1928–1941 |

2.9 |

5.8 |

13.9

|

| 1950s |

6.9 |

6.0 |

10.1

|

| 1960s |

4.2 |

5.2 |

7.1

|

| 1970s |

2.0 |

3.7 |

5.3

|

| 1980–1985 |

0.6 |

2.0 |

3.2

|

Both critics and supporters of communist rule often make comparisons

between the economic development of countries under communist rule and

non-communist countries, with the intention of certain economic

structures are superior to the other. All such comparisons are open to

challenge, both on the comparability of the states involved and the

statistics being used for comparison. No two countries are identical,

which makes comparisons regarding later economic development difficult;

Western Europe was more developed and industrialized than Eastern Europe

long before the Cold War; World War II damaged the economies of some

countries more than others; and East Germany had much of its industry

dismantled and moved to the Soviet Union for war reparations. For example, virtually every electrified and/or double tracked railroad in East Germany was reduced to a single track non-electrified railroad by Soviet demontage after World War II.

Advocates of Soviet-style economic planning have claimed the

system has in certain instances produced dramatic advances, including

rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union, especially during the

1930s. Critics of Soviet economic planning, in response, assert that new

research shows that the Soviet figures were partly fabricated,

especially those showing extremely high growth in the Stalin era. Growth

was high in the 1950s and 1960s, in some estimates much higher than

during the 1930s, but later declined and according to some estimates

became negative in the late 1980s. Before collectivization,

Russia had been the "breadbasket of Europe". Afterwards, the Soviet

Union became a net importer of grain, unable to produce enough food to

feed its own population.

China and Vietnam achieved much higher rates of growth after introducing market reforms such as socialism with Chinese characteristics starting in the late 1970s and 1980s, with higher growth rates being accompanied by declining poverty.

The communist states do not compare favorably when looking at nations

divided by the Cold War. North Korea versus South Korea; and East

Germany versus West Germany. East German productivity

relative to West German productivity was around 90 percent in 1936 and

around 60–65 percent in 1954. When compared to Western Europe, East

German productivity declined from 67 percent in 1950 to 50 percent

before the reunification in 1990. All the Eastern European national

economies had productivity far below the Western European average.

Some countries under communist rule with socialist economies

maintained consistently higher rates of economic growth than

industrialized Western countries with capitalist economies. From 1928 to

1985, the economy of the Soviet Union grew by a factor of 10 and GNP per capita grew more than fivefold. The Soviet economy started out at roughly 25 percent the size of the economy of the United States.

By 1955, it climbed to 40 percent. In 1965, the Soviet economy reached

50% of the contemporary United States economy and in 1977 it passed the

60 percent threshold. For the first half of the Cold War, most

economists were asking when, not if, the Soviet economy would overtake

the United States economy. Starting in the 1970s and continuing through

the 1980s, growth rates slowed down in the Soviet Union and throughout

the socialist bloc.

The reasons for this downturn are still a matter of debate among

economists, but one hypothesis is that the socialist planned economies

had reached the limits of the extensive growth model they were pursuing and the downturn was at least in part caused by their refusal or inability to switch to intensive growth.

Further, it could be argued that since the economies of countries such

as Russia were pre-industrial before the socialist revolutions, the high

economic growth rate could be attributed to industrialization.

Also while forms of economic growth associated with any economic

structure produce some winners and losers, some point out that high

growth rates under communist rule were associated with particularly

intense suffering and even mass starvation of the peasant population.

Unlike the slow market reforms in China and Vietnam where

communist rule continues, the abrupt end to central planning was

followed by a depression in many of the states of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe which chose to adopt the so-called economic shock therapy.

For example, in the Russian Federation GDP per capita decreased by

one-third between 1989 and 1996. As of 2003, all of them have positive

economic growth and almost all have a higher GDP/capita than before the

transition.

In general, critics of communist rule argue that socialist economies

remained behind the industrialized West in terms of economic development

for most of their existence while others assert that socialist

economies had growth rates that were sometimes higher than many

non-socialist economies, so they would have eventually caught up to the

West if those growth rates had been maintained. Some reject all

comparisons altogether, noting that the communist states started out

with economies that were generally much less developed to begin with.

Environmental policy

According to the

United States Department of Energy, the Communist states maintained a much higher level of

energy intensity

than either the Western nations or the Third World, at least after

1970, therefore energy-intensive development may have been reasonable as

the Soviet Union was an exporter of oil and China has vast supplies of

coal.

Criticism of communist rule include a focus on environmental disasters. One example is the gradual disappearance of the Aral Sea and a similar diminishing of the Caspian Sea

because of the diversion of the rivers that fed them. Another is the

pollution of the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea and the unique freshwater

environment of Lake Baikal. Many of the rivers were polluted and several, like the Vistula and Oder

rivers in Poland, were virtually ecologically dead. Over 70 percent of

the surface water in the Soviet Union was polluted. In 1988, only 30

percent of the sewage in the Soviet Union was treated properly.

Established health standards for air pollution

was exceeded by ten times or more in 103 cities in the Soviet Union in

1988. The air pollution problem was even more severe in Eastern Europe.

It caused a rapid growth in lung cancer,

forest die-back and damage to buildings and cultural heritages.

According to official sources, 58 percent of total agricultural land of

the former Soviet Union was affected by salinization, erosion, acidity, or waterlogging. Nuclear waste was dumped in the Sea of Japan,

the Arctic Ocean and in locations in the Far East. It was revealed in

1992 that in the city of Moscow there were 636 radioactive toxic waste

sites and 1,500 in Saint Petersburg.

According to the United States Department of Energy, socialist economies also maintained a much higher level of energy intensity than either the Western nations or the Third World. This analysis is confirmed by the Institute of Economic Affairs, with Mikhail Bernstam stating that economies of the Eastern Bloc had an energy intensity between twice and three times higher as economies of the West.

Some see the aforementioned examples of environmental degradation are

similar to what had occurred in Western capitalist countries during the

height of their drive to industrialize in the 19th century.

Others claim that Communist regimes did more damage than average,

primarily due to the lack of any popular or political pressure to

research environmentally friendly technologies.

Some ecological problems continue unabated after the fall of the

Soviet Union and are still major issues today, which has prompted

supporters of former ruling Communist parties to accuse their opponents

of holding a double standard. Nonetheless, other environmental problems have improved in every studied former Communist state.

However, some researchers argued that part of improvement was largely

due to the severe economic downturns in the 1990s that caused many

factories to close down.

Forced labour and deportations

A number of communist states also used forced labour

as a legal form of punishment for certain periods of time and again,

critics of these policies assert that many prisoners who were sentenced

to serve terms of imprisonment in forced labor camps such as the Gulag

were sent there for political rather than criminal reasons. Some of the

Gulag camps were located in very harsh environments, such as Siberia,

which resulted in the death of a significant fraction of inmates before

they could complete their prison sentences. Officially, the Gulag was

shut down in 1960, but it remained de facto in action for some time afterward. North Korea continues to maintain a network of prison and labor camps

that an estimated 200,000 people are imprisoned in. While the country

does not regularly deport its citizens, it maintains a system of

internal exile and banishment.

Many deaths were also caused by involuntary deportations of entire ethnic groups as part of the population transfer in the Soviet Union. Many Prisoners of War

taken during World War II were not released as the war ended and died

in the Gulags. Many German civilians died as a result of atrocities

committed by the Soviet army during the evacuation of East Prussia) and due to the policy of ethnic cleansing of Germans from the territories they lost due to the war during the expulsion of Germans after World War II.

Freedom of movement

The

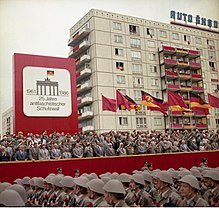

Berlin Wall was constructed in 1961 to stop emigration from

East Berlin to

West Berlin

and in the last phase of the wall's development the "death strip"

between fence and concrete wall gave guards a clear shot at would-be

escapees from the East.

In the literature on communist rule, many anticommunists have

asserted that communist regimes tend to impose harsh restrictions on the

freedom of movement.

These restrictions, they argue, are meant to stem the possibility of

mass emigration, which threatens to offer evidence pointing to

widespread popular dissatisfaction with their rule.

Between 1950 and 1961, 2.75 million East Germans moved to West

Germany. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 around 200,000 people

moved to Austria as the Hungarian-Austrian border temporarily opened.

From 1948 to 1953 hundreds of thousands of North Koreans moved to the

South, stopped only when emigration was clamped down after the Korean War.

In Cuba, 50,000 middle-class Cubans left between 1959 and 1961 after the Cuban Revolution

and the breakdown of Cuban-American relations. Following a period of

repressive measures by the Cuban government in the late 1960s and 1970s,

Cuba allowed for mass emigration of dissatisfied citizens, a policy

that resulted in the Mariel Boatlift of 1980, which led to a drop in emigration rates during the later months. In the 1990s, the economic crisis known as the Special Period coupled with the United States' tightening of the embargo led to desperate attempts to leave the island on balsas (rafts, tires and makeshift vessels).

Many Cubans currently continue attempts to emigrate to the United

States In total, according to some estimates, more than 1 million people

have left Cuba, around 10% of the population.

Between 1971 and 1998, 547,000 Cubans emigrated to the United States

alongside 700,000 neighboring Dominicans, 335,000 Haitians and 485,000

Jamaicans.

Since 1966, immigration to the United States was governed by the 1966

Cuban adjustment act, a United States law that applies solely to Cubans.

The ruling allows any Cuban national, no matter the means of the entry

into the United States, to receive a green card after being in the

country a year.

Havana has long argued that the policy has encouraged the illegal

exodus, deliberately ignoring and undervaluing the life-threatening

hardships endured by refugees.

After the victory of the communist North in the Vietnam War, over 2 million people in former South Vietnamese territory left the country (see Vietnamese boat people)

in the 1970s and 1980s. Another large group of refugees left Cambodia

and Laos. Restrictions on emigration from states ruled by communist

parties received extensive publicity. In the West, the Berlin wall

emerged as a symbol of such restrictions. During the Berlin Wall's

existence, sixty thousand people unsuccessfully attempted to emigrate

illegally from East Germany and received jail terms for such actions;

there were around five thousand successful escapes into West Berlin; and

239 people were killed trying to cross. Albania and North Korea

perhaps imposed the most extreme restrictions on emigration. From most

other communist regimes, legal emigration was always possible, though

often so difficult that attempted emigrants would risk their lives in

order to emigrate. Some of these states relaxed emigration laws

significantly from the 1960s onwards. Tens of thousands of Soviet

citizens emigrated legally every year during the 1970s.

Ideology

According to Klas-Göran Karlsson,

"[i]deologies are systems of ideas, which cannot commit crimes

independently. However, individuals, collectives and states that have

defined themselves as communist have committed crimes in the name of

communist ideology, or without naming communism as the direct source of

motivation for their crimes." Authors such as Daniel Goldhagen, John Gray, Richard Pipes and Rudolph Rummel consider the ideology of communism to be a significant, or at least partial, causative factor in the events under communist party rule. The Black Book of Communism claims an association between communism and criminality, arguing that "Communist regimes [...] turned mass crime into a full-blown system of government" while adding that this criminality lies at the level of ideology rather than state practice. On the other hand, Benjamin Valentino does not see a link between communism and mass killing,

arguing that killings occur when power is in the hands of one person or

a small number of people, when "powerful groups come to believe it is

the best available means to accomplish certain radical goals, counter

specific types of threats, or solve difficult military problem", or

there is a "revolutionary desire to bring about the rapid and radical

transformation of society."

Christopher J. Finlay argues that Marxism

legitimates violence without any clear limiting principle because it

rejects moral and ethical norms as constructs of the dominant class and

states that "it would be conceivable for revolutionaries to commit

atrocious crimes in bringing about a socialist system, with the belief

that their crimes will be retroactively absolved by the new system of

ethics put in place by the proletariat." According to Rustam Singh, Karl Marx

alluded to the possibility of peaceful revolution, but he emphasized

the need for violent revolution and "revolutionary terror" after the

failed Revolutions of 1848. According to Jacques Sémelin,

"communist systems emerging in the twentieth century ended up

destroying their own populations, not because they planned to annihilate

them as such, but because they aimed to restructure the 'social body'

from top to bottom, even if that meant purging it and recarving it to

suit their new Promethean political imaginaire."

Daniel Chirot and Clark McCauley

write that, especially in Stalin's Soviet Union, Mao's China and Pol

Pot's Cambodia, a fanatical certainty that socialism could be made to

work motivated communist leaders in "the ruthless dehumanization

of their enemies, who could be suppressed because they were

'objectively' and 'historically' wrong. Furthermore, if events did not

work out as they were supposed to, then that was because class enemies, foreign spies and saboteurs,

or worst of all, internal traitors were wrecking the plan. Under no

circumstances could it be admitted that the vision itself might be

unworkable, because that meant capitulation to the forces of reaction." Michael Mann writes that communist party

members were "ideologically driven, believing that in order to create a

new socialist society, they must lead in socialist zeal. Killings were

often popular, the rank-and-file as keen to exceed killing quotas as

production quotas."

According to Rummel, the killings committed by communist regimes

can best be explained as the result of the marriage between absolute

power and the absolutist ideology of Marxism.

Rummel states that "communism was like a fanatical religion. It had its

revealed text and its chief interpreters. It had its priests and their

ritualistic prose with all the answers. It had a heaven, and the proper

behavior to reach it. It had its appeal to faith. And it had its

crusades against nonbelievers. What made this secular religion so

utterly lethal was its seizure of all the state's instruments of force

and coercion and their immediate use to destroy or control all

independent sources of power, such as the church, the professions,

private businesses, schools, and the family." Rummels writes that Marxist communists saw the construction of their utopia

as "though a war on poverty, exploitation, imperialism and inequality.

And for the greater good, as in a real war, people are killed. And,

thus, this war for the communist utopia had its necessary enemy

casualties, the clergy, bourgeoisie, capitalists, wreckers,

counterrevolutionaries, rightists, tyrants, rich, landlords, and

noncombatants that unfortunately got caught in the battle. In a war

millions may die, but the cause may be well justified, as in the defeat

of Hitler and an utterly racist Nazism. And to many communists, the

cause of a communist utopia was such as to justify all the deaths."

Benjamin Valentino

writes the following "apparently high levels of political support for

murderous regimes and leaders should not automatically be equated with

support for mass killing itself. Individuals are capable of supporting

violent regimes or leaders while remaining indifferent or even opposed

to specific policies that these regimes and carried out." Valentino

quotes Vladimir Brovkin as saying that "a vote for the Bolsheviks in

1917 was not a vote for Red Terror or even a vote for a dictatorship of

the proletariat."

According to Valentino, such strategies were so violent because they

economically dispossess large numbers of people, commenting: "Social

transformations of this speed and magnitude have been associated with

mass killing for two primary reasons. First, the massive social

dislocations produced by such changes have often led to economic collapse, epidemics,

and, most important, widespread famines. ... The second reason that

communist regimes bent on the radical transformation of society have

been linked to mass killing is that the revolutionary changes they have

pursued have clashed inexorably with the fundamental interests of large

segments of their populations. Few people have proved willing to accept

such far-reaching sacrifices without intense levels of coercion." According to Jacques Sémelin,

"communist systems emerging in the twentieth century ended up

destroying their own populations, not because they planned to annihilate

them as such, but because they aimed to restructure the 'social body'

from top to bottom, even if that meant purging it and recarving it to

suit their new Promethean political imaginaire."

International politics and relations

Imperialism

As an ideology, Marxism–Leninism stresses militant opposition to imperialism. Lenin considered imperialism "the highest stage of capitalism" and in 1917 made declarations of the unconditional right of self-determination and secession

for the national minorities of Russia. During the Cold War, communist

states have been accused of, or criticized for, exercising imperialism

by giving military assistance and in some cases intervening directly on

behalf of Communist movements that were fighting for control,

particularly in Asia and Africa.

Western critics accused the Soviet Union and the People's

Republic of China of practicing imperialism themselves, and communist

condemnations of Western imperialism hypocritical. The attack on and

restoration of Moscow's control of countries that had been under the

rule of the tsarist empire, but briefly formed newly independent states

in the aftermath of the Russian Civil War (including Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan), have been condemned as examples of Soviet imperialism. Similarly, Stalin's forced reassertion of Moscow's rule of the Baltic states in World War II has been condemned as Soviet imperialism. Western critics accused Stalin of creating satellite states in Eastern Europe after the end of World War II. Western critics also condemned the intervention of Soviet forces during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the Prague Spring and the war in Afghanistan

as aggression against popular uprisings. Maoists argued that the Soviet

Union had itself become an imperialist power while maintaining a

socialist façade (social imperialism). China's reassertion of central control over territories on the frontiers of the Qing dynasty, particularly Tibet, has also been condemned as imperialistic by some critics.

Support of terrorism

Some states under communist rule have been criticized for directly supporting terrorist groups such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the Red Army Faction and the Japanese Red Army. North Korea has been implicated in terrorist acts such as Korean Air Flight 858.

World War II

According to Richard Pipes, the Soviet Union shares some responsibility for World War II. Pipes argues that both Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini

used the Soviet Union as a model for their own regimes and that Hitler

privately considered Stalin a "genius". According to Pipes, Stalin

privately hoped that another world war would weaken his foreign enemies

and allow him to assert Soviet power internationally. Before Hitler took

power, Stalin allowed the testing and production of German weapons that

were forbidden by the Versailles Treaty

to occur on Soviet territory. Stalin is also accused of weakening

German opposition to the Nazis before Hitler's rule began in 1933.

During the 1932 German elections, for instance, he forbade the German

Communists from collaborating with the Social Democrats. These parties

together gained more votes than Hitler and some have later surmised

could have prevented him from becoming Chancellor.

Leadership

Professor Matthew Krain states that many scholars have pointed to revolutions and civil wars

as providing the opportunity for radical leaders and ideologies to gain

power and the preconditions for mass killing by the state.

Professor Nam Kyu Kim writes that exclusionary ideologies are critical

to explaining mass killing, but the organizational capabilities and

individual characteristics of revolutionary leaders, including their

attitudes towards risk and violence, are also important. Besides opening

up political opportunities for new leaders to eliminate their political

opponents, revolutions bring to power leaders who are more apt to

commit large-scale violence against civilians in order to legitimize and

strengthen their own power. Genocide scholar Adam Jones states that the Russian Civil War was very influential on the emergence of leaders like Stalin and accustomed people to "harshness, cruelty, terror." Martin Malia called the "brutal conditioning" of the two World Wars important to understanding communist violence, although not its source.

Historian Helen Rappaport describes Nikolay Yezhov, the bureaucrat in charge of the NKVD during the Great Purge,

as a physically diminutive figure of "limited intelligence" and "narrow

political understanding. [...] Like other instigators of mass murder

throughout history, [he] compensated for his lack of physical stature

with a pathological cruelty and the use of brute terror." Russian and world history

scholar John M. Thompson places personal responsibility directly on

Stalin. According to Thompson, "much of what occurred only makes sense

if it stemmed in part from the disturbed mentality, pathological

cruelty, and extreme paranoia of Stalin himself. Insecure, despite

having established a dictatorship over the party and country, hostile

and defensive when confronted with criticism of the excesses of

collectivization and the sacrifices required by high-tempo

industrialization, and deeply suspicious that past, present, and even

yet unknown future opponents were plotting against him, Stalin began to

act as a person beleaguered. He soon struck back at enemies, real or

imaginary."

Professors Pablo Montagnes and Stephane Wolton argue that the purges in

the Soviet Union and China can be attributed to the "personalist"

leadership of Stalin and Mao, who were incentivized by having both

control of the security apparatus used to carry out the purges and

control of the appointment of replacements for those purged. Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek attributes Mao allegedly viewing human life as disposable to Mao's "cosmic perspective" on humanity.

Mass killings

Many mass killings

occurred under 20th-century communist regimes. Death estimates vary

widely, depending on the definitions of deaths included. The higher

estimates of mass killings account for crimes against civilians by

governments, including executions, destruction of population through

man-made hunger and deaths during forced deportations, imprisonment and

through forced labor. Terms used to define these killings include "mass

killing", "democide", "politicide", "classicide", a broad definition of "genocide", "crimes against humanity", "holocaust", and "repression".

Scholars such as Stéphane Courtois, Steven Rosefielde, Rudolph Rummel and Benjamin Valentino

have argued that communist regimes were responsible for tens or even

hundreds of millions of deaths. These deaths mostly occurred under the

rule of Stalin and Mao, therefore these particular periods of communist

rule in Soviet Russia and China receive considerable attention in The Black Book of Communism, although other communist regimes have also caused high number of deaths, not least the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, which is often acclaimed to have killed more of its citizens than any other in history.

These accounts often divide their death toll estimates into two

categories, namely executions of people who had received the death

penalty for various charges, or deaths that occurred in prison; and

deaths that were not caused directly by the regime, as the people in

question were not executed and did not die in prison, but are considered

to have died as an indirect result of state or communist party

policies. Those scholars argue that most victims of communist rule fell

in this category, which is often the subject of considerable

controversy.

In most communist states, the death penalty was a legal form of

punishment for most of their existence, with a few exceptions. While the

Soviet Union formally abolished the death penalty between 1947 and

1950, critics argue that this did nothing to curb executions and acts of

genocide.

Critics also argue that many of the convicted prisoners executed by

authorities under communist rule were not criminals but political

dissidents. Stalin's Great Purge in the late 1930s (from roughly 1936–1938) is given as the most prominent example of the hypothesis. With regard to deaths not caused directly by state or party authorities, The Black Book of Communism

points to famine and war as the indirect causes of what they see as

deaths for which communist regimes were responsible. In this sense, the Soviet famine of 1932–33 and the Great Leap Forward

are often described as man-made famines. These two events alone killed a

majority of the people seen as victims of communist states by estimates

such as Courtois'. Courtois also blames Mengistu Haile Mariam's regime for having exacerbated the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia by imposing unreasonable political and economic burdens on the population.

Estimates

The authors of The Black Book of Communism, Norman Davies,

Rummel and others have attempted to give estimates of the total number

of deaths for which communist rule of a particular state in a particular

period was responsible, or the total for all states under communist

rule. The question is complicated by the lack of hard data and by biases

inherent in any estimation. The number of people killed under Stalin's

rule in the Soviet Union by 1939 has been estimated as 3.5–8 million by

Geoffrey Ponton, 6.6 million by V. V. Tsaplin and 10–11 million by Alexander Nove. The number of people killed under Stalin's rule by the time of his death in 1953 has been estimated as 1–3 million by Stephen G. Wheatcroft, 6–9 million by Timothy D. Snyder, 13–20 million by Rosefielde, 20 million by Courtois and Martin Malia, 20 to 25 million by Alexander Yakovlev, 43 million by Rummel and 50 million by Davies.

The number of people killed under Mao's rule in the People's Republic

of China has been estimated at 19.5 million by Wang Weizhi, 27 million by John Heidenrich, between 38 and 67 million by Kurt Glaser and Stephan Possony, between 32 and 59 million by Robert L. Walker, over 50 million by Rosefielde, 65 million by Cortois and Malia, well over 70 million by Jon Halliday and Jung Chang in Mao: The Unknown Story and 77 million by Rummel.

Aerial night view of the Korean Peninsula showing

South Korea illuminated and few lights in Communist North Korea

The authors of The Black Book of Communism have also estimated

that 9.3 million people were killed under communist rule in other

states: 2 million in North Korea, 2 million in Cambodia, 1.7 million in

Africa, 1.5 million in Afghanistan, 1 million in Vietnam, 1 million in

Eastern Europe and 150,000 in Latin America. Rummel has estimated that

1.7 million were killed by the government of Vietnam, 1.6 million in

North Korea (not counting the 1990s famine), 2 million in Cambodia and

2.5 million in Poland and Yugoslavia.

Valentino estimates that 1 to 2 million were killed in Cambodia, 50,000

to 100,000 in Bulgaria, 80,000 to 100,000 in East Germany, 60,000 to

300,000 in Romania, 400,000 to 1,500,000 in North Korea, and 80,000 to

200,000 in North and South Vietnam.

Between the authors Wiezhi, Heidenrich, Glaser, Possony, Ponton,

Tsaplin and Nove, Stalin's Soviet Union and Mao's China have an

estimated total death rate ranging from 23 million to 109 million. The Black Book of Communism

asserts that roughly 94 million died under all communist regimes while

Rummel believed around 144.7 million died under six communist regimes.

Valentino claims that between 21 and 70 million deaths are attributable

to the Communist regimes in the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of

China and Democratic Kampuchea alone. Jasper Becker, author of Hungry Ghosts,

claims that if the death tolls from the famines caused by communist

regimes in China, the Soviet Union, Cambodia, North Korea, Ethiopia and

Mozambique are added together, the figure could be close to 90 million.

These estimates are the three highest numbers of victims blamed on

communism by any notable study. However, the totals that include

research by Wiezhi, Heidenrich, Glasser, Possony, Ponton, Tsaplin and

Nove do not include other periods of time beyond Stalin or Mao's rule,

thus it may be possible when including other communist states to reach

higher totals. In a 25 January 2006 resolution condemning the crimes of communist regimes, the Council of Europe cited the 94 million total reached by the authors of the Black Book of Communism.

Explanations have been offered for the discrepancies in the number of estimated victims of communist regimes:

- First, all these numbers are estimates derived from incomplete

data. Researchers often have to extrapolate and interpret available

information in order to arrive at their final numbers.

- Second, different researchers work with different definitions of

what it means to be killed by a regime. As noted by several scholars,

the vast majority of victims of communist regimes did not die as a

result of direct government orders but as an indirect result of state

policy. There is no agreement on the question of whether communist

regimes should be held responsible for their deaths and if so, to what

degree. The low estimates may count only executions and labor camp

deaths as instances of killings by communist regimes while the high

estimates may be based on the argument that communist regimes were

responsible for all deaths resulting from famine or war.

- Some of the writers make special distinction for Stalin and Mao, who

all agree are responsible for the most extensive pattern of severe

crimes against humanity, but they include little to no statistics on

losses of life after their rule.

- Another reason is sources available at the time of writing. More

recent researchers have access to many of the official archives of

communist regimes in East Europe and Soviet Union. However, many of

archives in Russia for the period after Stalin's death are still closed.

- Finally, this is a highly politically charged field, with nearly all

researchers having been accused of a pro-communist or anti-communist

bias at one time or another.

Debate over famines

According to historian J. Arch Getty, over half of the 100 million deaths which are attributed to communism were due to famines. Stéphane Courtois

posits that many communist regimes caused famines in their efforts to

forcibly collectivize agriculture and systematically used it as a weapon

by controlling the food supply and distributing food on a political

basis. Courtois states that "in the period after 1918, only Communist

countries experienced such famines, which led to the deaths of hundreds

of thousands, and in some cases millions, of people. And again in the

1980s, two African countries that claimed to be Marxist–Leninist, Ethiopia and Mozambique, were the only such countries to suffer these deadly famines."

Scholars Stephen G. Wheatcroft, R. W. Davies and Mark Tauger reject the idea that the Ukrainian famine

was an act of genocide that was intentionally inflicted by the Soviet

government. Getty posits that the "overwhelming weight of opinion among

scholars working in the new archives is that the terrible famine of the

1930s was the result of Stalinist bungling and rigidity rather than some

genocidal plan." Wheatcroft argued that the Soviet government's

policies during the famine were criminal acts of fraud and manslaughter,

though not outright murder or genocide. In contrast according to Simon Payaslian, the scholarly consensus classifies the Holodomor as a genocide. Russian novelist and historian Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn opined on 2 April 2008 in Izvestia that the 1930s famine in the Ukraine was no different from the Russian famine of 1921 as both were caused by the ruthless robbery of peasants by Bolshevik grain procurements.

Pankaj Mishra questions Mao's direct responsibility for the Great Chinese Famine,

noting that "[a] great many premature deaths also occurred in newly

independent nations not ruled by erratic tyrants." Mishra cites Nobel

laureate Amartya Sen's research demonstrating that democratic India suffered more excess mortality

from starvation and disease in the second half of the 20th century than

China did. Sen wrote that "India seems to manage to fill its cupboard

with more skeletons every eight years than China put there in its years

of shame."

Benjamin Valentino

writes: "Although not all the deaths due to famine in these cases were

intentional, communist leaders directed the worst effects of famine

against their suspected enemies and used hunger as a weapon to force

millions of people to conform to the directives of the state." Daniel Goldhagen

says that in some cases deaths from famine should not be distinguished

from mass murder, commenting: "Whenever governments have not alleviated

famine conditions, political leaders decided not to say no to mass death

– in other words, they said yes." Goldhagen says that instances of this

occurred in the Mau Mau Rebellion, the Great Leap Forward, the Nigerian Civil War, the Eritrean War of Independence, and the War in Darfur. Martin Shaw

posits that if a leader knew the ultimate result of their policies

would be mass death by famine, and they continue to enact them anyway,

these deaths can be understood as intentional.

Historians and journalists, such as Seumas Milne and Jon Wiener, have criticized the emphasis on communism when assigning blame for famines. In a 2002 article for The Guardian, Milne mentions "the moral blindness displayed towards the record of colonialism",

and he writes: "If Lenin and Stalin are regarded as having killed those

who died of hunger in the famines of the 1920s and 1930s, then

Churchill is certainly responsible for the 4 million deaths in the

avoidable Bengal famine of 1943." Milne laments that while "there is a much-lauded Black Book of Communism, [there exists] no such comprehensive indictment of the colonial record." Weiner makes a similar assertion while comparing the Holodomor and the Bengal famine of 1943, stating that Winston Churchill's role in the Bengal famine "seems similar to Stalin's role in the Ukrainian famine." Historian Mike Davis, author of Late Victorian Holocausts, draws comparisons between the Great Chinese Famine and the Indian famines of the late 19th century,

arguing that in both instances the governments which oversaw the

response to the famines deliberately chose not to alleviate conditions

and as such bear responsibility for the scale of deaths in said famines.

Historian Michael Ellman

is critical of the fixation on a "uniquely Stalinist evil" when it

comes to excess deaths from famines. Ellman posits that mass deaths from

famines are not a "uniquely Stalinist evil", commenting that throughout

Russian history, famines, and droughts have been a common occurrence, including the Russian famine of 1921–1922,

which occurred before Stalin came to power. He also states that famines

were widespread throughout the world in the 19th and 20th centuries in

countries such as India, Ireland, Russia and China. According to Ellman,

the G8 "are

guilty of mass manslaughter or mass deaths from criminal negligence

because of their not taking obvious measures to reduce mass deaths" and

Stalin's "behaviour was no worse than that of many rulers in the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Personality cults

Both anti-communists and communists have criticized the personality cults of many communist rulers, especially the cults of Stalin, Mao, Fidel Castro and Kim Il-sung. In the case of North Korea, the personality cult of Kim Il-sung was associated with inherited leadership, with the succession of Kim's son Kim Jong-il in 1994 and grandson Kim Jong-un in 2011. Cuban communists have also been criticized for planning an inherited leadership, with the succession of Raúl Castro following his brother's illness in mid-2006.

Political repression

Large-scale

political repression under communist rule has been the subject of

extensive historical research by scholars and activists from a diverse

range of perspectives. A number of researchers on this subject are

former Eastern bloc communists who become disillusioned with their

ruling parties, such as Alexander Yakovlev and Dmitri Volkogonov. Similarly, Jung Chang, one of the authors of Mao: The Unknown Story, was a Red Guard in her youth. Others are disillusioned former Western communists, including several of the authors of The Black Book of Communism. Robert Conquest,

another former communist, became one of the best-known writers on the

Soviet Union following the publication of his influential account of the

Great Purge in The Great Terror,

which at first was not well received in some left-leaning circles of

Western intellectuals. Following the end of the Cold War, much of the

research on this topic has focused on state archives previously

classified under communist rule.

The level of political repression experienced in states under

communist rule varied widely between different countries and historical

periods. The most rigid censorship was practiced by the Soviet Union

under Stalin (1922–1953), China under Mao during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and the communist regime in North Korea throughout its rule (1948–present). Under Stalin's rule, political repression in the Soviet Union included executions of Great Purge victims and peasants deemed "kulaks" by state authorities; the Gulag

system of forced labor camps; deportations of ethnic minorities; and

mass starvations during the Soviet famine of 1932–1933, caused by either

government mismanagement, or by some accounts, caused deliberately. The Black Book of Communism also details the mass starvations resulting from Great Leap Forward in China and the Killing Fields in Cambodia.

Although political repression in the Soviet Union was far more

extensive and severe in its methods under Stalin's rule than in any

other period, authors such as Richard Pipes, Orlando Figes and works such as the Black Book of Communism argue that a reign of terror began within Russia under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin immediately after the October Revolution, and continued by the Red Army and the Cheka over the country during the Russian Civil War. It included summary executions

of hundreds of thousands of "class enemies" by Cheka; the development

of the system of labor camps, which would later lay the foundation for

the Gulags; and a policy of food requisitioning during the civil war,

which was partially responsible for a famine causing three to ten

million deaths.

Alexander Yakovlev's

critique of political repression under communist rule focus on the

treatment of children, which he numbers in the millions, of alleged

political opponents. His accounts stress cases in which children of

former imperial officers and peasants were held as hostages and

sometimes shot during the civil war. His account of the Second World War

highlights cases in which the children of soldiers who had surrendered

were the victims of state reprisal. Some children, Yakovlev notes,

followed their parents to the Gulags, suffering an especially high

mortality rate. According to Yakovlev, in 1954 there were 884,057

"specially resettled" children under the age of sixteen. Others were

placed in special orphanages run by the secret police in order to be

reeducated, often losing even their names, and were considered socially

dangerous as adults. Other accounts focus on extensive networks of civilian informants,

consisting of either volunteers, or those forcibly recruited. These

networks were used to collect intelligence for the government and report

cases of dissent.

Many accounts of political repression in the Soviet Union highlight

cases in which internal critics were classified as mentally ill

(diagnosed with disorders such as sluggishly progressing schizophrenia) and incarcerated in mental hospitals). The fact that workers in the Soviet Union were not allowed to organize independent, non-state trade union has also been presented as a case of political repression in the Soviet Union.

Various accounts stressing a relationship between political repression

and communist rule focus on the suppression of internal uprisings by

military force such as the Tambov rebellion and the Kronstadt rebellion during the Russian Civil War as well as the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in China. Ex-communist dissident Milovan Đilas, among others, focused on the relationship between political repression and the rise of a powerful new class of party bureaucrats, called the nomenklatura, that had emerged under communist rule and exploited the rest of the population.

Political system

Historian Anne Applebaum asserts that "without exception, the Leninist belief in the one-party state was and is characteristic of every communist regime" and "the Bolshevik use of violence was repeated in every communist revolution." Phrases said by Vladimir Lenin and Cheka founder Felix Dzerzhinsky were deployed all over the world. Applebaum notes that as late as 1976 Mengistu Haile Mariam unleashed a Red Terror in Ethiopia. Lenin is quoted as saying to his colleagues in the Bolshevik government: "If we are not ready to shoot a saboteur and White Guardist, what sort of revolution is that?"

Historian Robert Conquest

stressed that events such as Stalin's purges were not contrary to the

principles of Leninism, but rather a natural consequence of the system

established by Lenin, who personally ordered the killing of local groups

of class enemy hostages. Alexander Yakovlev, architect of perestroika and glasnost

and later head of the Presidential Commission for the Victims of

Political Repression, elaborates on this point, stating: "The truth is

that in punitive operations Stalin did not think up anything that was

not there under Lenin: executions, hostage taking, concentration camps,

and all the rest." Historian Robert Gellately

concurs, arguing that "[t]o put it another way, Stalin initiated very

little that Lenin had not already introduced or previewed."

Philosopher Stephen Hicks of Rockford College

ascribes the violence characteristic of 20th-century communist party

rule to these collectivist regimes' abandonment of protections of civil rights and rejection of the values of civil society.

Hicks writes that whereas "in practice every liberal capitalist country

has a solid record for being humane, for by and large respecting rights

and freedoms, and for making it possible for people to put together

fruitful and meaningful lives", in communist party rule "practice has

time and again proved itself more brutal than the worst dictatorships

prior to the twentieth century. Each socialist regime has collapsed into

dictatorship and begun killing people on a huge scale."

Author Eric D. Weitz

says that events such as mass killing in communist states are a natural

consequence of the failure of the rule of law, seen commonly during

periods of social upheaval in the 20th century. For both communist and

non-communist mass killings, "genocides occurred at moments of extreme

social crisis, often generated by the very policies of the regimes."

According to this view, mass killings are not inevitable but are

political decisions. Soviet and Communist studies scholar Steven Rosefielde

writes that communist rulers had to choose between changing course and

"terror-command" and more often than not chose the latter. Sociologist Michael Mann

argues that a lack of institutionalized authority structures meant that

a chaotic mix of both centralized control and party factionalism were

factors to the events.

Social development

Starting with the first five-year plan

in the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Soviet leaders

pursued a strategy of economic development concentrating the country's

economic resources on heavy industry and defense rather than on consumer goods.

This strategy was later adopted in varying degrees by communist leaders

in Eastern Europe and the Third World. For many Western critics of

communist strategies of economic development, the unavailability of

consumer goods common in the West in the Soviet Union was a case in

point of how communist rule resulted in lower standards of living.

The allegation that communist rule resulted in lower standards of

living sharply contrasted with communist arguments boasting of the

achievements of the social and cultural programs of the Soviet Union and

other communist states. For instance, Soviet leaders boasted of

guaranteed employment, subsidized food and clothing, free health care,

free child care and free education. Soviet leaders also touted early

advances in women's equality, particularly in Islamic areas of Soviet Central Asia.

Eastern European communists often touted high levels of literacy in

comparison with many parts of the developing world. A phenomenon called Ostalgie,

nostalgia for life under Soviet rule, has been noted amongst former

members of Communist countries, now living in Western capitalist states,

particularly those who lived in the former East Germany.

The effects of communist rule on living standards have been

harshly criticized. Jung Chang stresses that millions died in famines in

communist China and North Korea.

Some studies conclude that East Germans were shorter than West Germans

probably due to differences in factors such as nutrition and medical

services. According to some researchers, life satisfaction increased in East Germany after the reunification. Critics of Soviet rule charge that the Soviet education system was full of propaganda

and of low quality. United States government researchers pointed out

the fact that the Soviet Union spent far less on health care than

Western nations and noted that the quality of Soviet health care was

deteriorating in the 1970s and 1980s. In addition, the failure of Soviet

pension and welfare programs to provide adequate protection was noted

in the West.

After 1965, life expectancy

began to plateau or even decrease, especially for males, in the Soviet

Union and Eastern Europe while it continued to increase in Western

Europe.

This divergence between two parts of Europe continued over the course

of three decades, leading to a profound gap in the mid-1990s. Life

expectancy sharply declined after the change to market economy in most

of the states of the former Soviet Union, but may now have started to

increase in the Baltic states. In several Eastern European nations, life expectancy started to increase immediately after the fall of communism.

The previous decline for males continued for a time in some Eastern

European nations, like Romania, before starting to increase.

In The Politics of Bad Faith, conservative writer David Horowitz

painted a picture of horrendous living standards in the Soviet Union.

Horowitz claimed that in the 1980s rationing of meat and sugar was

common in the Soviet Union. Horowitz cited studies suggesting the

average intake of red meat for a Soviet citizen was half of what it had been for a subject of the tsar in 1913, that blacks under apartheid

in South Africa owned more cars per capita and that the average welfare

mother in the United States received more income in a month than the

average Soviet worker could earn in a year. According to Horowitz, the

only area of consumption in which the Soviets excelled was the ingestion

of hard liquor.

Horowitz also noted that two-thirds of the households had no hot water

and a third had no running water at all. Horowitz cited the government

newspaper Izvestia,

noting a typical working-class family of four was forced to live for

eight years in a single eight by eight foot room before marginally

better accommodation became available. In his discussion of the Soviet

housing shortage, Horowitz stated that the shortage was so acute that at

all times 17 percent of Soviet families had to be physically separated

for want of adequate space. A third of the hospitals had no running

water and the bribery of doctors and nurses to get decent medical

attention and even amenities like blankets in Soviet hospitals was not

only common, but routine. In his discussion of Soviet education,

Horowitz stated that only 15 percent of Soviet youth were able to attend

institutions of higher learning compared to 34 percent in the United

States.

However, large segments of citizens of many former communist today

states say that the standard of living has fallen since the end of the

Cold War, with majorities of citizens in the former East Germany and Romania were polled as saying that life was better under Communism.

In terms of living standards, economist Michael Ellman

asserts that in international comparisons state socialist nations

compared favorably with capitalist nations in health indicators such as

infant mortality and life expectancy. Amartya Sen's

own analysis of international comparisons of life expectancy found that

several communist countries made significant gains and commented "one

thought that is bound to occur is that communism is good for poverty

removal".

Poverty exploded following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991,

tripling to more than one-third of Russia's population in just three

years. By 1999, around 191 million people in former Eastern Bloc countries and Soviet republics were living on less than $5.50 a day.

Left-wing criticism

Communist countries, states, areas and local communities have been based on the rule of parties proclaiming a basis in Marxism–Leninism,

an ideology which is not supported by all Marxists, communists and

leftists. Many communists disagree with many of the actions undertaken

by ruling Communist parties during the 20th century.

Elements of the left opposed to Bolshevik plans before they were put into practice included the revisionist Marxists, such as Eduard Bernstein, who denied the necessity of a revolution. Anarchists (who had differed from Marx and his followers since the split in the First International), many of the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Marxist Mensheviks supported the overthrow of the tsar, but vigorously opposed the seizure of power by Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

Criticisms of Communist rule from the left continued after the creation of the Soviet state. The anarchist Nestor Makhno led the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine against the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War and the Socialist Revolutionary Fanya Kaplan tried to assassinate Lenin. Bertrand Russell

visited Russia in 1920 and regarded the Bolsheviks as intelligent, but

clueless and planless. In her books about Soviet Russia after the

revolution, My Disillusionment in Russia and My Further Disillusionment in Russia, Emma Goldman condemned the suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion as a "massacre". Eventually, the Left Socialist Revolutionaries broke with the Bolsheviks.

By anti-revisionists

Anti-revisionists (which includes radical Marxist–Leninist factions, Hoxhaists and Maoists) criticize the rule of the communist states by claiming that they were state capitalist states ruled by revisionists.

Though the periods and countries defined as state capitalist or

revisionist varies among different ideologies and parties, all of them

accept that the Soviet Union was socialist during Stalin's time. Maoists view the Soviet Union and most of its satellites as "state capitalist" as a result of de-Stalinization;

some of them also view modern China in this light, believing that the

People's Republic of China became state capitalist after Mao's death.

Hoxhaists believe that the People's Republic of China was always state

capitalist and uphold Socialist Albania as the only socialist state after the Soviet Union under Stalin.

By left communists

Left communists

claim that the "communist" or "socialist" states or "people's states"

were actually state capitalist and thus cannot be called "socialist". Some of the earliest critics of Leninism were the German-Dutch left communists, including Herman Gorter, Anton Pannekoek and Paul Mattick. Though most left communists see the October Revolution positively, their analysis concludes that by the time of the Kronstadt revolt the revolution had degenerated due to various historical factors. Rosa Luxemburg

was another communist who disagreed with Lenin's organizational methods

which eventually led to the creation of the Soviet Union.

Amadeo Bordiga

wrote about his view of the Soviet Union as a capitalist society. In

contrast to those produced by the Trotskyists, Bordiga's writings on the

capitalist nature of the Soviet economy also focused on the agrarian

sector. Bordiga displayed a kind of theoretical rigidity which was both

exasperating and effective in allowing him to see things differently. He

wanted to show how capitalist social relations existed in the kolkhoz and in the sovkhoz,

one a cooperative farm and the other the straight wage-labor state

farm. He emphasized how much of agrarian production depended on the

small privately owned plots (he was writing in 1950) and predicted quite

accurately the rates at which the Soviet Union would start importing

wheat after Russia had been such a large exporter from the 1880s to

1914. In Bordiga's conception, Stalin and later Mao, Ho Chi Minh and Che

Guevara were "great romantic revolutionaries" in the 19th century

sense, i.e. bourgeois revolutionaries. He felt that the Stalinist

regimes that came into existence after 1945 were just extending the

bourgeois revolution, i.e. the expropriation of the Prussian Junker class by the Red Army through their agrarian policies and through the development of the productive forces.

By Trotskyists

After the split between Leon Trotsky and Stalin, Trotskyists

have argued that Stalin transformed the Soviet Union into a

bureaucratic and repressive one-party state and that all subsequent

Communist states ultimately followed a similar path because they copied Stalinism. There are various terms used by Trotskyists to define such states, such as "degenerated workers' state" and "deformed workers' state", "state capitalist" or "bureaucratic collectivist".

While Trotskyists are Leninists, there are other Marxists who reject

Leninism entirely, arguing that the Leninist principle of democratic centralism was the source of the Soviet Union's slide away from communism.

By other socialists

In October 2017, Nathan J. Robinson

wrote an article titled "How to Be a Socialist without Being an

Apologist for the Atrocities of Communist Regimes", arguing that it is

"incredibly easy to be both in favor of socialism and against the crimes

committed by 20th century communist regimes. All it takes is a

consistent, principled opposition to authoritarianism".

Counter-criticism

Some academics and writers argue that anti-communist

narratives have exaggerated the extent of political repression and

censorship in states under communist party rule and drawn comparisons

with what they see as atrocities that were perpetrated by capitalist

countries, particularly during the Cold War. They include Mark Aarons, Vincent Bevins, Noam Chomsky, Jodi Dean, Kristen Ghodsee, Seumas Milne and Michael Parenti.

Parenti argues that communist states experienced greater economic development than they would have otherwise, or that their leaders were forced to take harsh measures to defend their countries against the Western Bloc during the Cold War. In addition, Parenti states that communist party rule provided some human rights such as economic, social and cultural rights not found under capitalist states

such as that everyone is treated equal regardless of education or

financial stability; that any citizen can keep a job; or that there is a

more efficient and equal distribution of resources.

Professors Paul Greedy and Olivia Ball report that communist parties

pressed Western governments to include economic rights in the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights.

Professor David L. Hoffmann

argues that many actions of communist party rule were rooted in the

response Western governments gave during World War I and that communist

party rule institutionalized them.

While noting "its brutalities and failures", Milne argues that "rapid

industrialisation, mass education, job security and huge advances in

social and gender equality" are not accounted and the dominant account

of communist party rule "gives no sense of how communist regimes renewed

themselves after 1956 or why western leaders feared they might overtake

the capitalist world well into the 1960s."