From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Measles | |

|---|---|

A child showing a classic 4-day measles rash.

|

|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | B05 |

| ICD-9 | 055 |

| DiseasesDB | 7890 |

| MedlinePlus | 001569 |

| eMedicine | derm/259 emerg/389 ped/1388 |

| Patient UK | Measles |

| MeSH | D008457 |

Measles, also known as morbilli, or rubeola is a highly contagious infection caused by the measles virus.[1] Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than 40 °C (104.0 °F), cough, runny nose, and red eyes.[1][2] Two or three days after the start of symptoms small white spots may form inside the mouth, known as Koplik's spots. A red, flat rash which usually starts on the face and then spreads to the rest of the body typically begins three to five days after the start of symptoms.[2] Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and lasts 7–10 days.[3][4] Complications occur in about 30% and may include: diarrhea, blindness, inflammation of the brain, and pneumonia among others.[3][5] Rubella (German measles) and roseola are different diseases.[6]

Measles is an airborne disease which spreads easily through the coughs and sneezes of those infected. It may also be spread through contact with saliva or nasal secretions.[3] Nine out of ten people who are not immune who share living space with an infected person will catch it. People are infectious to others from four days before to four days after the start of the rash.[5] People usually only get the disease at most once.[3] Testing for the virus in suspected cases is important for public health efforts.[5]

The measles vaccine is effective at preventing the disease. Vaccination has resulted in a 75% decrease in deaths from the disease since the year 2000 with about 85% of children globally being vaccinated. No specific treatment is available. Supportive care, however, may improve outcomes.[3] This may include giving oral rehydration solution (slightly sweet and salty fluids), healthy food, and medications to help with the fever.[3][4] Antibiotics may be used if a bacteria infection such as pneumonia occurs. Vitamin A supplementation is also recommended in the developing world.[3]

Measles affects about 20 million people a year,[1] primarily in the developing areas of Africa and Asia.[3] It resulted in about 96,000 deaths in 2013 down from 545,000 deaths in 1990.[7] In 1980, the disease is estimated to have caused 2.6 million deaths per year.[3] Before immunization in the United States between three and four million cases occurred a year.[5] Most of those who are infected and who die are less than five years old.[3] The risk of death among those infected is usually 0.2%,[5] but may be up to 10% in those who have malnutrition.[3] It is not believed to affect animals.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The classic signs and symptoms of measles include four-day fevers (the 4 D's) and the three C's—cough, coryza (head cold), and conjunctivitis (red eyes)—along with fever and rashes. The fever may reach up to 40 °C (104 °F). Koplik's spots seen inside the mouth are pathognomonic (diagnostic) for measles, but are temporary and therefore rarely seen. Their recognition, before the affected person reaches maximum infectivity, can be used to reduce spread of epidemics.[8]

The characteristic measles rash is classically described as a generalized red maculopapular rash that begins several days after the fever starts. It starts on the back of the ears and, after a few hours, spreads to the head and neck before spreading to cover most of the body, often causing itching. The measles rash appears two to four days after the initial symptoms and lasts for up to eight days. The rash is said to "stain", changing color from red to dark brown, before disappearing.[9]

Complications

Complications with measles are relatively common, ranging from mild complications such as diarrhea to serious complications such as pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia),[10] otitis media,[11] acute brain inflammation[12] (and very rarely SSPE—subacute sclerosing panencephalitis),[13] and corneal ulceration (leading to corneal scarring).[14] Complications are usually more severe in adults who catch the virus.[15] The death rate in the 1920s was around 30% for measles pneumonia.[16]Between 1987 and 2000, the case fatality rate across the United States was three measles-attributable deaths per 1000 cases, or 0.3%.[17] In underdeveloped nations with high rates of malnutrition and poor healthcare, fatality rates have been as high as 28%.[17] In immunocompromised persons (e.g., people with AIDS) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.[18] Risk factors for severe measles and its complications include: malnutrition,[19][20] underlying immunodeficiency,[19] pregnancy,[19][21] and vitamin A deficiency.[19][22]

Cause

Measles is caused by the measles virus, a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus of the genus Morbillivirus within the family Paramyxoviridae. The virus was first isolated in 1954 by Nobel Laureate John F. Enders and Thomas Peebles, who were careful to point out that the isolations were made from patients who had Koplik's spots.[23] Humans are the natural hosts of the virus; no other animal reservoirs are known to exist. This highly contagious virus is spread by coughing and sneezing via close personal contact or direct contact with secretions. Risk factors for measles virus infection include: immunodeficiency caused by HIV or AIDS,[24] leukemia,[25] alkylating agents, or corticosteroid therapy, regardless of immunization status;[19] travel to areas where measles is endemic or contact with travelers to endemic areas;[19] and the loss of passive, inherited antibodies before the age of routine immunization.[19]

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of measles requires a history of fever of at least three days, with at least one of the three C's (cough, coryza, conjunctivitis). Observation of Koplik's spots is also diagnostic of measles.[8][26][27]Alternatively, laboratory diagnosis of measles can be done with confirmation of positive measles IgM antibodies[28] or isolation of measles virus RNA from respiratory specimens.[29] For people unable to undergo phlebotomy, saliva can be collected for salivary measles-specific IgA testing.[30] Positive contact with other patients known to have measles adds strong epidemiological evidence to the diagnosis. The contact with any infected person in any way, including semen through sex, saliva, or mucus, can cause infection.[27]

Prevention

In developed countries, children are immunized against measles at 12 months, generally as part of a three-part MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella). The vaccination is generally not given earlier than this because sufficient antimeasles immunoglobulins (antibodies) are acquired via the placenta from the mother during pregnancy may persist to prevent the vaccine viruses from being effective.[citation needed] A second dose is usually given to children between the ages of four and five, to increase rates of immunity. Vaccination rates have been high enough to make measles relatively uncommon. Adverse reactions to vaccination are rare, with fever and pain at the injection site being the most common. Life-threatening adverse reactions occur in less than one per million vaccinations (<0 .0001="" class="reference" id="cite_ref-cubavac_31-0" sup="">[31]In developing countries where measles is highly endemic, WHO doctors recommend two doses of vaccine be given at six and nine months of age. The vaccine should be given whether the child is HIV-infected or not.[32] The vaccine is less effective in HIV-infected infants than in the general population, but early treatment with antiretroviral drugs can increase its effectiveness.[33] Measles vaccination programs are often used to deliver other child health interventions, as well, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, antiparasite medicine and vitamin A supplements, and so contribute to the reduction of child deaths from other causes.[34]

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for measles. Most patients with uncomplicated measles will recover with rest and supportive treatment. It is, however, important to seek medical advice if the patient becomes sicker, as they may be developing complications.Some patients will develop pneumonia as a sequel to the measles. Other complications include ear infections, bronchitis (either viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis), and brain inflammation.[35] Brain inflammation from measles has a mortality rate of 15%. While there is no specific treatment for brain inflammation from measles, antibiotics are required for bacterial pneumonia, sinusitis, and bronchitis that can follow measles.

All other treatment addresses symptoms, with ibuprofen or paracetamol to reduce fever and pain and, if required, a fast-acting bronchodilator for cough. As for aspirin, some research has suggested a correlation between children who take aspirin and the development of Reye syndrome.[36] Some research has shown aspirin may not be the only medication associated with Reye, and even antiemetics have been implicated,[37] with the point being the link between aspirin use in children and Reye's syndrome development is weak at best, if not actually nonexistent.[36][38] Nevertheless, most health authorities still caution against the use of aspirin for any fevers in children under 16.[39][40][41][42]

The use of vitamin A in treatment has been investigated. A systematic review of trials into its use found no significant reduction in overall mortality, but it did reduce mortality in children aged under two years.[43][44][45] A specific drug treatment for measles ERDRP-0519 has shown promising results in animal studies, but has not yet been tested in humans.[46][47][48]

Prognosis

The majority of patients survive measles, though in some cases, complications may occur, which may include bronchitis, and—in about 1 in 100,000 cases[49]—panencephalitis, which is usually fatal.[50]Acute measles encephalitis is another serious risk of measles virus infection. It typically occurs two days to one week after the breakout of the measles exanthem and begins with very high fever, severe headache, convulsions and altered mentation. A patient may become comatose, and death or brain injury may occur.[51]

Epidemiology

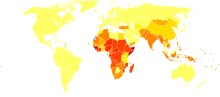

Disability-adjusted life year for measles per 100,000 inhabitants in 2002.

no data

≤ 10

10–25

25–50

50–75

75–100

100–250

250–500

500–750

750–1000

1000–1500

1500–2000

≥ 2000

Measles is extremely infectious and its continued circulation in a community depends on the generation of susceptible hosts by birth of children. In communities which generate insufficient new hosts the disease will die out. This concept was first recognized in measles by Bartlett in 1957, who referred to the minimum number supporting measles as the critical community size (CCS).[52]

Analysis of outbreaks in island communities suggested that the CCS for measles is c. 250,000.[53]

In 2011, the WHO estimated that there were about 158,000 deaths caused by measles. This is down from 630,000 deaths in 1990.[54] In developed countries, death occurs in 1 to 2 cases out of every 1,000 (0.1% - 0.2%).[55] In populations with high levels of malnutrition and a lack of adequate healthcare, mortality can be as high as 10%. In cases with complications, the rate may rise to 20–30%.[56] Increased immunization has led to an estimated 78% drop in measles deaths among UN member states.[57][58] This reduction made up 25% of the decline in mortality in children under five during this period.[citation needed]

| WHO-Region | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | 1,240,993 | 481,204 | 520,102 | 316,224 | 12,125 |

| Region of the Americas | 257,790 | 218,579 | 1,755 | 19 | 3,100 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 341,624 | 59,058 | 38,592 | 15,069 | 2,214 |

| European Region | 851,849 | 234,827 | 37,421 | 37,332 | 2,430 |

| South-East Asia Region | 199,535 | 224,925 | 61,975 | 83,627 | 1,540 |

| Western Pacific Region | 1,319,640 | 155,490 | 176,493 | 128,016 | 34,310 |

| Worldwide | 4,211,431 | 1,374,083 | 836,338 | 580,287 | 55,719 |

Even in countries where vaccination has been introduced, rates may remain high. In Ireland, vaccination was introduced in 1985. There were 99,903 cases that year. Within two years, the number of cases had fallen to 201, but this fall was not sustained. Measles is a leading cause of vaccine-preventable childhood mortality. Worldwide, the fatality rate has been significantly reduced by a vaccination campaign led by partners in the Measles Initiative: the American Red Cross, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Foundation, UNICEF and the WHO. Globally, measles fell 60% from an estimated 873,000 deaths in 1999 to 345,000 in 2005.[34] Estimates for 2008 indicate deaths fell further to 164,000 globally, with 77% of the remaining measles deaths in 2008 occurring within the Southeast Asian region.[63]

In 2006–07 there were 12,132 cases in 32 European countries: 85% occurred in five countries: Germany, Italy, Romania, Switzerland and the UK. 80% occurred in children and there were 7 deaths.[64]

Five out of six WHO regions have set goals to eliminate measles, and at the 63rd World Health Assembly in May 2010, delegates agreed a global target of a 95% reduction in measles mortality by 2015 from the level seen in 2000, as well as to move towards eventual eradication. However, no specific global target date for eradication has yet been agreed to as of May 2010.[65][66]

History

The Antonine Plague,[67] 165–180 AD, also known as the Plague of Galen, who described it, was probably smallpox or measles. The epidemic may have claimed the life of Roman emperor Lucius Verus. Total deaths have been estimated at five million.[68] Estimates of the timing of evolution of measles seem to suggest this plague was something other than measles. The first scientific description of measles and its distinction from smallpox and chickenpox is credited to the Persian physician Rhazes (860–932), who published The Book of Smallpox and Measles.[69] Given what is now known about the evolution of measles, this account is remarkably timely, as recent work that examined the mutation rate of the virus indicates the measles virus emerged from rinderpest (Cattle Plague) as a zoonotic disease between 1100 and 1200 AD, a period that may have been preceded by limited outbreaks involving a virus not yet fully acclimated to humans.[70] This agrees with the observation that measles requires a susceptible population of >500,000 to sustain an epidemic, a situation that occurred in historic times following the growth of medieval European cities.[71]

Measles is an endemic disease, meaning it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations not exposed to measles, exposure to the new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox. Two years later, measles was responsible for the deaths of half the population of Honduras, and had ravaged Mexico, Central America, and the Inca civilization.[73]

Between roughly 1855 to 2005 measles has been estimated to have killed about 200 million people worldwide.[74] Measles killed 20 percent of Hawaii's population in the 1850s.[75] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[76] In the 19th century, the disease killed 50% of the Andamanese population.[77] In 1954, the virus causing the disease was isolated from an 13-year-old boy from the United States, David Edmonston, and adapted and propagated on chick embryo tissue culture.[78] To date, 21 strains of the measles virus have been identified.[79] While at Merck, Maurice Hilleman developed the first successful vaccine.[80] Licensed vaccines to prevent the disease became available in 1963.[81] An improved measles vaccine became available in 1968.[82]