From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Part of the rotational spectrum of trifluoroiodomethane, CF3I.[notes 1] Each rotational transition is labeled with the quantum numbers, J, of the final and initial states, and is extensively split by the effects of nuclear quadrupole coupling with the 127I nucleus.

Rotational spectroscopy is concerned with the measurement of the energies of transitions between quantized rotational states of molecules in the gas phase. The spectra of polar molecules can be measured in absorption or emission by microwave spectroscopy[1] or by far infrared spectroscopy. The rotational spectra of non-polar molecules cannot be observed by those methods, but can be observed and measured by Raman spectroscopy.

Rotational spectroscopy is sometimes referred to as pure rotational spectroscopy to distinguish it from rotational-vibrational spectroscopy where changes in rotational energy occur together with changes in vibrational energy, and also from ro-vibronic spectroscopy (or just vibronic spectroscopy) where rotational, vibrational and electronic energy changes occur simultaneously.

For rotational spectroscopy, molecules are classified according to symmetry into spherical top, linear and symmetric top; analytical expressions can be derived for the rotational energy terms of these molecules. Analytical expressions cannot be derived for the fourth category, asymmetric top, but spectra can be fitted using numerical methods. The rotational energies are derived theoretically by considering the molecules to be rigid rotors and then applying extra terms to account for centrifugal distortion, fine structure, hyperfine structure and Coriolis coupling. Fitting the spectra to the theoretical expressions gives numerical values of the angular moments of inertia from which very precise values of molecular bond lengths and angles can be derived in favorable cases. In the presence of an electrostatic field there is Stark splitting which allows molecular electric dipole moments to be determined.

An important application of rotational spectroscopy is in exploration of the chemical composition of the interstellar medium using radio telescopes.

Applications

Rotational spectroscopy has primarily been used to investigate fundamental aspects of molecular physics. It is a uniquely precise tool for the determination of molecular structure in gas phase molecules. It can be used to establish barriers to internal rotation such as that associated with the rotation of the CH3 group relative to the C6H4Cl group in chlorotoluene (C7H7Cl).[2] When fine or hyperfine structure can be observed, the technique also provides information on the electronic structures of molecules. Much of current understanding of the nature of weak molecular interactions such as van der Waals, hydrogen and halogen bonds has been established through rotational spectroscopy. In connection with radio astronomy, the technique has a key role in exploration of the chemical composition of the interstellar medium. Microwave transitions are measured in the laboratory and matched to emissions from the interstellar medium using a radio telescope. NH3 was the first stable polyatomic molecule to be identified in the interstellar medium.[3] The measurement of chlorine monoxide[4] is important for atmospheric chemistry. Current projects in astrochemistry involve both laboratory microwave spectroscopy and observations made using modern radiotelescopes such as the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA).[5] Unlike NMR, Infrared and UV-Visible spectroscopies, microwave spectroscopy has not yet found widespread application in analytical chemistry.Overview

A molecule in the gas phase is free to rotate relative to a set of mutually orthogonal axes of fixed orientation in space, centered on the center of mass of the molecule. Free rotation is not possible for molecules in liquid or solid phases due to the presence of intermolecular forces. Rotation about each unique axis is associated with a set of quantized energy levels dependent on the moment of inertia about that axis and a quantum number. Thus, for linear molecules the energy levels are described by a single moment of inertia and a single quantum number, , which defines the magnitude of the rotational angular momentum.

, which defines the magnitude of the rotational angular momentum.For nonlinear molecules which are symmetric rotors (or symmetric tops - see next section), there are two moments of inertia and the energy also depends on a second rotational quantum number,

, which defines the vector component of rotational angular momentum along the principal symmetry axis.[6] Analysis of spectroscopic data with the expressions detailed below results in quantitative determination of the value(s) of the moment(s) of inertia. From these precise values of the molecular structure and dimensions may be obtained.

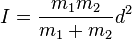

, which defines the vector component of rotational angular momentum along the principal symmetry axis.[6] Analysis of spectroscopic data with the expressions detailed below results in quantitative determination of the value(s) of the moment(s) of inertia. From these precise values of the molecular structure and dimensions may be obtained.For a linear molecule, analysis of the rotational spectrum provides values for the rotational constant[notes 2] and the moment of inertia of the molecule, and, knowing the atomic masses, can be used to determine the bond length directly. For diatomic molecules this process is straightforward. For linear molecules with more than two atoms it is necessary to measure the spectra of two or more isotopologues, such as 16O12C32S and 16O12C34S. This allows a set of simultaneous equations to be set up and solved for the bond lengths).[notes 3] It should be noted that a bond length obtained in this way is slightly different from the equilibrium bond length. This is because there is zero-point energy in the vibrational ground state, to which the rotational states refer, whereas the equilibrium bond length is at the minimum in the potential energy curve. The relation between the rotational constants is given by

For other molecules, if the spectra can be resolved and individual transitions assigned both bond lengths and bond angles can be deduced. When this is not possible, as with most asymmetric tops, all that can be done is to fit the spectra to three moments of inertia calculated from an assumed molecular structure. By varying the molecular structure the fit can be improved, giving a qualitative estimate of the structure. Isotopic substitution is invaluable when using this approach to the determination of molecular structure.

Classification of molecular rotors

In quantum mechanics the free rotation of a molecule is quantized, so that the rotational energy and the angular momentum can take only certain fixed values, which are related simply to the moment of inertia, , of the molecule. For any molecule, there are three moments of inertia:

, of the molecule. For any molecule, there are three moments of inertia:  ,

,  and

and  about three mutually orthogonal axes A, B, and C with the origin at the center of mass of the system. The general convention, used in this article, is to define the axes such that

about three mutually orthogonal axes A, B, and C with the origin at the center of mass of the system. The general convention, used in this article, is to define the axes such that  , with axis

, with axis  corresponding to the smallest moment of inertia. Some authors, however, define the

corresponding to the smallest moment of inertia. Some authors, however, define the  axis as the molecular rotation axis of highest order.

axis as the molecular rotation axis of highest order.The particular pattern of energy levels (and, hence, of transitions in the rotational spectrum) for a molecule is determined by its symmetry. A convenient way to look at the molecules is to divide them into four different classes, based on the symmetry of their structure. These are

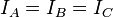

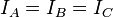

- Spherical tops (spherical rotors) All three moments of inertia are equal to each other:

. Examples of spherical tops include phosphorus tetramer (P4), carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and other tetrahalides, methane (CH4), silane, (SiH4), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) and other hexahalides. The molecules all belong to the cubic point groups Td or Oh.

. Examples of spherical tops include phosphorus tetramer (P4), carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and other tetrahalides, methane (CH4), silane, (SiH4), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) and other hexahalides. The molecules all belong to the cubic point groups Td or Oh.

- Linear molecules. For a linear molecule the moments of inertia are related by

. For most purposes,

. For most purposes,  can be taken to be zero. Examples of linear molecules include dioxygen, O2, dinitrogen, N2, carbon monoxide, CO, hydroxy radical, OH, carbon dioxide, CO2, hydrogen cyanide, HCN, carbonyl sulfide, OCS, acetylene (ethyne, HC≡CH) and dihaloethynes. These molecules belong to the point groups C∞v or D∞h

can be taken to be zero. Examples of linear molecules include dioxygen, O2, dinitrogen, N2, carbon monoxide, CO, hydroxy radical, OH, carbon dioxide, CO2, hydrogen cyanide, HCN, carbonyl sulfide, OCS, acetylene (ethyne, HC≡CH) and dihaloethynes. These molecules belong to the point groups C∞v or D∞h

- Symmetric tops (symmetric rotors) A symmetric top is a molecule in which two moments of inertia are the same,

or

or  . By definition a symmetric top must have a 3-fold or higher order rotation axis. As a matter of convenience, spectroscopists divide molecules into two classes of symmetric tops, Oblate symmetric tops (saucer or disc shaped) with

. By definition a symmetric top must have a 3-fold or higher order rotation axis. As a matter of convenience, spectroscopists divide molecules into two classes of symmetric tops, Oblate symmetric tops (saucer or disc shaped) with  and Prolate symmetric tops (rugby football, or cigar shaped) with

and Prolate symmetric tops (rugby football, or cigar shaped) with  . The spectra look rather different, and are instantly recognizable. Examples of symmetric tops include

. The spectra look rather different, and are instantly recognizable. Examples of symmetric tops include

- As a detailed example, ammonia has a moment of inertia IC = 4.4128 × 10−47 kg m2 about the 3-fold rotation axis, and moments IA = IB = 2.8059 × 10−47 kg m2 about any axis perpendicular to the C3 axis. Since the unique moment of inertia is larger than the other two, the molecule is an oblate symmetric top.[8]

- Asymmetric tops (asymmetric rotors) The three moments of inertia have different values. Examples of small molecules that are asymmetric tops include water, H2O and nitrogen dioxide, NO2 whose symmetry axis of highest order is a 2-fold rotation axis. Most large molecules are asymmetric tops.

Selection rules

Microwave and far-infrared spectra

Transitions between rotational states can be observed in molecules with a permanent electric dipole moment.[9][notes 4] A consequence of this rule is that no microwave spectrum can be observed for centrosymmetric linear molecules such as N2 (dinitrogen) or HCCH (ethyne), which are non-polar. Tetrahedral molecules such as CH4 (methane), which have both a zero dipole moment and isotropic polarizability, would not have a pure rotation spectrum but for the effect of centrifugal distortion; when the molecule rotates about a 3-fold symmetry axis a small dipole moment is created, allowing a weak rotation spectrum to be observed by microwave spectroscopy.[10]With symmetric tops, the selection rule for electric-dipole-allowed pure rotation transitions is ΔK = 0, ΔJ = ±1. Since these transitions are due to absorption (or emission) of a single photon with a spin of one, conservation of angular momentum implies that the molecular angular momentum can change by at most one unit.[11] Moreover the quantum number K is limited to have values between and including +J to -J.[12]

Raman spectra

For Raman spectra the molecules undergo transitions in which an incident photon is absorbed and another scattered photon is emitted. The general selection rule for such a transition to be allowed is that the molecular polarizability must be anisotropic, which means that it is not the same in all directions.[13] Polarizability is a 3-dimensional tensor that can be represented as an ellipsoid. The polarizability ellipsoid of spherical top molecules is in fact spherical so those molecules show no rotational Raman spectrum. For all other molecules both Stokes and anti-Stokes lines[notes 5] can be observed and they have similar intensities due to the fact that many rotational states are thermally populated. The selection rule for linear molecules is ΔJ = 0, ±2. The reason for the value of 2 is that the polarizability returns to the same value twice during a rotation.[14] The selection rule for symmetric top molecules is- ΔK = 0

- If K = 0, then ΔJ = ±2

- If K ≠ 0, then ΔJ = 0, ±1, ±2

Units

The units used for rotational constants depend on the type of measurement. With infrared spectra, the unit of measurement is usually wavenumbers per cm, written as cm−1 and shown with the symbol . Wavenumbers per cm is literally the number of waves in one centimeter, or the reciprocal of wavelength in cm. On the other hand, microwave spectra are usually measured in Gigahertz. The relationship between the two units is derived from the expression

. Wavenumbers per cm is literally the number of waves in one centimeter, or the reciprocal of wavelength in cm. On the other hand, microwave spectra are usually measured in Gigahertz. The relationship between the two units is derived from the expressionEffect of vibration on rotation

The population of vibrationally excited states follows a Boltzmann distribution, so low frequency vibrational states are appreciably populated even at room temperatures. As the moment of inertia is higher when a vibration is excited, the rotational constants, B decrease. Consequently, the rotation frequencies in each vibration state are different from each other. This can give rise to "satellite" lines in the rotational spectrum. An example is provided by cyanodiacetylene, H-C≡C−C≡C-C≡N,[16]Further, there is a fictitious force, Coriolis coupling, between the vibrational motion of the nuclei in the rotating (non-inertial) frame. However, as long as the vibrational quantum number does not change (i.e., the molecule is in only one state of vibration), the effect of vibration on rotation is not important, because the time for vibration is much shorter than the time required for rotation. The Coriolis coupling is often negligible, too, if one is interested in low vibrational and rotational quantum numbers only.

Effect of rotation on vibrational spectra

Historically, the theory of rotational energy levels was developed to account for observations of vibration-rotation spectra of gases in infrared spectroscopy, which was used before microwave spectroscopy had become practical. To a first approximation the energy of rotation is added to, or subtracted from the energy of vibration. The vibration-rotation wavenumbers of transitions for a harmonic oscillator with rigid rotor are given byRotational constants obtained from infrared measurements are in good accord with those obtained by microwave spectroscopy while the latter usually offers greater precision.

Structure of rotational spectra

Spherical top

Spherical top molecules have no net dipole moment. A pure rotational spectrum cannot be observed by absorption or emission spectrocopy because there is no permanent dipole moment whose rotation can be accelerated by the electric field of an incident photon. Also the polarizability is isotropic, so that pure rotational transitions cannot be observed by Raman spectroscopy either. Nevertheless, rotational constants can be obtained by ro-vibrational spectroscopy. This occurs when a molecule is polar in the vibrationally excited state. For example, the molecule methane is a symmetric top but the asymmetric C-H stretching band shows rotational fine structure in the infrared spectrum, illustrated in rovibrational coupling. This spectrum is also interesting because it shows clear evidence of Coriolis coupling in the asymmetric structure of the band.Linear molecules

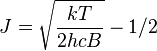

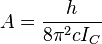

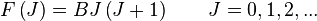

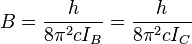

The rigid rotor is a good starting point from which to construct a model of a rotating molecule. It is assumed that component atoms are point masses connected by rigid bonds. A linear molecule lies on a single axis and each atom moves on the surface of a sphere around the centre of mass. The two degrees of rotational freedom correspond to the spherical coordinates θ and φ which describe the direction of the molecular axis, and the quantum state is determined by two quantum numbers J and M. J defines the magnitude of the rotational angular momentum, and M its component about an axis fixed in space, such as an external electric or magnetic field. In the absence of external fields, the energy depends only on J. Under the rigid rotor model, the rotational energy levels, F(J), of the molecule can be expressed as,

is the rotational constant of the molecule and is related to the moment of inertia of the molecule. In a linear molecule the moment of inertia about an axis perpendicular to the molecular axis is unique, that is,

is the rotational constant of the molecule and is related to the moment of inertia of the molecule. In a linear molecule the moment of inertia about an axis perpendicular to the molecular axis is unique, that is, , so

, soSelection rules dictate that during emission or absorption the rotational quantum number has to change by unity; i.e.,

. Thus, the locations of the lines in a rotational spectrum will be given by

. Thus, the locations of the lines in a rotational spectrum will be given by denotes the lower level and

denotes the lower level and  denotes the upper level involved in the transition.

denotes the upper level involved in the transition.The diagram illustrates rotational transitions that obey the

=1 selection rule. The dashed lines show how these transitions map onto features that can be observed experimentally. Adjacent

=1 selection rule. The dashed lines show how these transitions map onto features that can be observed experimentally. Adjacent  transitions are separated by 2B in the observed spectrum. Frequency or wavenumber units can also be used for the x axis of this plot.

transitions are separated by 2B in the observed spectrum. Frequency or wavenumber units can also be used for the x axis of this plot.Rotational line intensities

The probability of a transition taking place is the most important factor influencing the intensity of an observed rotational line. This probability is proportional to the population of the initial state involved in the transition. The population of a rotational state depends on two factors. The number of molecules in an excited state with quantum number J, relative to the number of molecules in the ground state, NJ/N0 is given by the Boltzmann distribution as

,

,

Combining the two factors[18]

Centrifugal distortion

When a molecule rotates, the centrifugal force pulls the atoms apart. As a result, the moment of inertia of the molecule increases, thus decreasing the value of , when it is calculated using the expression for the rigid rotor. To account for this a centrifugal distortion correction term is added to the rotational energy levels of the diatomic molecule.[20]

, when it is calculated using the expression for the rigid rotor. To account for this a centrifugal distortion correction term is added to the rotational energy levels of the diatomic molecule.[20] is the centrifugal distortion constant.

is the centrifugal distortion constant.Therefore, the line positions for the rotational mode change to

An assumption underlying these expressions is that the molecular vibration follows simple harmonic motion. In the harmonic approximation the centrifugal constant

can be derived as

can be derived as and

and

is the harmonic vibration frequency, follows. If anharmonicity is to be taken into account, terms in higher powers of J should be added to the expressions for the energy levels and line positions.[20] A striking example concerns the rotational spectrum of hydrogen fluoride which was fitted to terms up to [J(J+1)]5.[21]

is the harmonic vibration frequency, follows. If anharmonicity is to be taken into account, terms in higher powers of J should be added to the expressions for the energy levels and line positions.[20] A striking example concerns the rotational spectrum of hydrogen fluoride which was fitted to terms up to [J(J+1)]5.[21]Oxygen

The electric dipole moment of the dioxygen molecule, O2 is zero, but the molecule is paramagnetic with two unpaired electrons so that there are magnetic-dipole allowed transitions which can be observed by microwave spectroscopy. The unit electron spin has three spatial orientations with respect to the given molecular rotational angular momentum vector, K, so that each rotational level is split into three states, J = K + 1, K, and K - 1, each J state of this so-called p-type triplet arising from a different orientation of the spin with respect to the rotational motion of the molecule. The energy difference between successive J terms in any of these triplets is about 2 cm−1 (60 GHz), with the single exception of J = 1←0 difference which is about 4 cm−1. Selection rules for magnetic dipole transitions allow transitions between successive members of the triplet (ΔJ = ±1) so that for each value of the rotational angular momentum quantum number K there are two allowed transitions. The 16O nucleus has zero nuclear spin angular momentum, so that symmetry considerations demand that K have only odd values.[22][23]Symmetric top

For symmetric rotors a quantum number J is associated with the total angular momentum of the molecule. For a given value of J, there is a 2J+1- fold degeneracy with the quantum number, M taking the values +J ...0 ... -J. The third quantum number, K is associated with rotation about the principal rotation axis of the molecule. In the absence of an external electrical field, the rotational energy of a symmetric top is a function of only J and K and, in the rigid rotor approximation, the energy of each rotational state is given by and

and  for a prolate symmetric top molecule or

for a prolate symmetric top molecule or  for an

for an oblate molecule.

This gives the transition wavenumbers as

Asymmetric top

The quantum number J refers to the total angular momentum, as before. Since there are three independent moments of inertia, there are two other independent quantum numbers to consider, but the term values for an asymmetric rotor cannot be derived in closed form. They are obtained by individual matrix diagonalization for each J value. Formulae are available for molecules whose shape approximates to that of a symmetric top.[26]

The water molecule is an important example of an asymmetric top. It has an intense pure rotation spectrum in the far infrared region, below about 200 cm−1. For this reason far infrared spectrometers have to be freed of atmospheric water vapour either by purging with a dry gas or by evacuation. The spectrum has been analyzed in detail.[27]

Quadrupole splitting

When a nucleus has a spin quantum number, I, greater than 1/2 it has a quadrupole moment. In that case, coupling of nuclear spin angular momentum with rotational angular momentum causes splitting of the rotational energy levels. If the quantum number J of a rotational level is greater than I, 2I+1 levels are produced; but if J is less than I, 2J+1 levels result. The effect is known as hyperfine splitting. For example, with 14N (I = 1) in HCN, all levels with J > 0 are split into 3. The energy of the sub-levels are proportional to the nuclear quadrupole moment and a function of F and J. where F = J+I, J+I-1, ..., 0, ... |J-I|. Thus, observation of nuclear quadrupole splitting permits the magnitude of the nuclear quadrupole moment to be determined.[28] This is an alternative method to the use of nuclear quadrupole resonance spectroscopy. The selection rule for rotational transitions becomes[29]Stark and Zeeman effects

In the presence of a static external electric field the 2J+1 degeneracy of each rotational state is partly removed, an instance of a Stark effect. For example in linear molecules each energy level is split into J+1 components. The extent of splitting depends on the square of the electric field strength and the square of the dipole moment of the molecule.[30] In principle this provides a means to determine the value of the molecular dipole moment with high precision. Examples include carbonyl sulfide, OCS, with μ = 0.71521 ± 0.00020 Debye. However, because the splitting depends on μ2, the orientation of the dipole must be deduced from quantum mechanical considerations.[31]A similar removal of degeneracy will occur when a paramagnetic molecule is placed in a magnetic field, an instance of the Zeeman effect. Most species which can be observed in the gaseous state are diamagnetic . Exceptions, known as odd molecules, include nitric oxide, NO, nitrogen dioxide, NO2, some chlorine oxides and the hydroxyl radical. The Zeeman effect has been observed with dioxygen, O2[32]

. Examples of spherical tops include

. Examples of spherical tops include  . For most purposes,

. For most purposes,  or

or  . By definition a symmetric top must have a 3-fold or higher order

. By definition a symmetric top must have a 3-fold or higher order  and

and  . The spectra look rather different, and are instantly recognizable. Examples of symmetric tops include

. The spectra look rather different, and are instantly recognizable. Examples of symmetric tops include

,

,