From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The special theory of relativity is known for its paradoxes: the twin paradox and the ladder-in-barn paradox, for example. Neither are true paradoxes; they merely expose flaws in our understanding, and point the way toward deeper understanding of nature. The ladder paradox exposes the breakdown of simultaneity, while the twin paradox highlights the distinctions of accelerated frames of reference.

So it is with the paradox of a charged particle at rest in a gravitational field; it is a paradox between the theories of electrodynamics and general relativity.

in addition to its rest-frame

in addition to its rest-frame  Coulomb field. This radiation electric field has an accompanying magnetic field, and the whole oscillating electromagnetic radiation field propagates independently of the accelerated charge, carrying away momentum and energy. The energy in the radiation is provided by the work that accelerates the charge. We understand a photon to be the quantum of the electromagnetic radiation field, but the radiation field is a classical concept.

Coulomb field. This radiation electric field has an accompanying magnetic field, and the whole oscillating electromagnetic radiation field propagates independently of the accelerated charge, carrying away momentum and energy. The energy in the radiation is provided by the work that accelerates the charge. We understand a photon to be the quantum of the electromagnetic radiation field, but the radiation field is a classical concept.

The theory of general relativity is built on the principle of the equivalence of gravitation and inertia. This means that it is impossible to distinguish through any local measurement whether one is in a gravitational field or being accelerated. An elevator out in deep space, far from any planet, could mimic a gravitational field to its occupants if it could be accelerated continuously "upward". Whether the acceleration is from motion or from gravity makes no difference in the laws of physics. This can also be understood in terms of the equivalence of so-called gravitational mass and inertial mass. The mass in Newton's law of gravity (gravitational mass) is the same as the mass in Newton's second law of motion (inertial mass). They cancel out when equated, with the result discovered by Galileo that all bodies fall at the same rate in a gravitational field, independent of their mass. This was famously demonstrated on the Moon during the Apollo 15 mission, when a hammer and a feather were dropped at the same time and, of course, struck the surface at the same time.

Closely tied in with this equivalence is the fact that gravity vanishes in free fall. For objects falling in an elevator whose cable is cut, all gravitational forces vanish, and things begin to look like the free-floating absence of forces one sees in videos from the International Space Station. One can find the weightlessness of outer space right here on earth: just jump out of an airplane. It is a lynchpin of general relativity that everything must fall together in free fall. Just as with acceleration versus gravity, no experiment should be able to distinguish the effects of free fall in a gravitational field, and being out in deep space far from any forces.

Equivalently, we can think about a charged particle at rest in a laboratory on the surface of the earth. Since we know the earth's gravitational field of 1 g is equivalent to being accelerated constantly upward at 1 g, and we know a charged particle accelerated upward at 1 g would radiate, why don't we see radiation from charged particles at rest in the laboratory? It would seem that we could distinguish between a gravitational field and acceleration, because an electric charge apparently only radiates when it is being accelerated through motion, but not through gravitation.

The key is to realize that the laws of electrodynamics, the Maxwell equations, hold only in an inertial frame. That is, in a frame in which no forces act locally. This could be free fall under gravity, or far in space away from any forces. The surface of the earth is not an inertial frame. It is being constantly accelerated. We know the surface of the earth is not an inertial frame because an object at rest there may not remain at rest—objects at rest fall to the ground when released. So we cannot naively formulate expectations based on the Maxwell equations in this frame. It is remarkable that we now understand the special-relativistic Maxwell equations do not hold, strictly speaking, on the surface of the earth—even though they were of course discovered in electrical and magnetic experiments conducted in laboratories on the surface of the earth. Nevertheless, in this case we cannot apply the Maxwell equations to the description of a falling charge relative to a "supported", non-inertial observer.

The Maxwell equations can be applied relative to an observer in free fall, because free-fall is an inertial frame. So the starting point of considerations is to work in the free-fall frame in a gravitational field—a "falling" observer. In the free-fall frame the Maxwell equations have their usual, flat spacetime form for the falling observer. In this frame, the electric and magnetic fields of the charge are simple: the falling electric field is just the Coulomb field of a charge at rest, and the magnetic field is zero. As an aside, note that we are building in the equivalence principle from the start, including the assumption that a charged particle falls equally as fast as a neutral particle. Let us see if any contradictions arise.

Now we are in a position to establish what an observer at rest in a gravitational field, the supported observer, will see. Given the electric and magnetic fields in the falling frame, we merely have to transform those fields into the frame of the supported observer. This is not a Lorentz transformation, because the two frames have a relative acceleration. Instead we must bring to bear the machinery of general relativity.

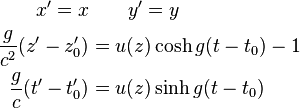

In this case our gravitational field is fictitious because it can be transformed away in an accelerating frame. Unlike the total gravitational field of the earth, here we are assuming that spacetime is locally flat, so that the curvature tensor vanishes. Equivalently, the lines of gravitational acceleration are everywhere parallel, with no convergences measurable in the laboratory. Then the most general static, flat-space, cylindrical metric and line element can be written:

is the speed of light,

is the speed of light,  is proper time,

is proper time,  are the usual coordinates of space and time,

are the usual coordinates of space and time,  is the acceleration of the gravitational field, and

is the acceleration of the gravitational field, and  is an arbitrary function of the coordinate but must approach the observed Newtonian value of

is an arbitrary function of the coordinate but must approach the observed Newtonian value of  . This is the metric for the gravitational field measured by the supported observer.

. This is the metric for the gravitational field measured by the supported observer.

Meanwhile, the metric in the frame of the falling observer is simply the Minkowski metric:

So a falling charge will appear to radiate to a supported observer, as expected. What about a supported charge, then? Does it not radiate due to the equivalence principle? To answer this question, start again in the falling frame.

In the falling frame, the supported charge appears to be accelerated uniformly upward. The case of constant acceleration of a charge is treated by Rohrlich [1] in section 5-3. He finds a charge uniformly accelerated at rate

uniformly accelerated at rate  has a radiation rate given by the Lorentz invariant:

has a radiation rate given by the Lorentz invariant:

.

.

The radiation from the supported charge is something of a curiosity: where does it go? Boulware (1980) [2] finds that the radiation goes into a region of spacetime inaccessible to the co-accelerating, supported observer. In effect, a uniformly accelerated observer has an event horizon, and there are regions of spacetime inaccessible to this observer. de Almeida and Saa (2006) [3] have a more-accessible treatment of the event horizon of the accelerated observer.

So it is with the paradox of a charged particle at rest in a gravitational field; it is a paradox between the theories of electrodynamics and general relativity.

Recap of Key Points of Gravitation and Electrodynamics

It is a standard result from the Maxwell equations of classical electrodynamics that an accelerated charge radiates. That is, it produces an electric field that falls off as in addition to its rest-frame

in addition to its rest-frame  Coulomb field. This radiation electric field has an accompanying magnetic field, and the whole oscillating electromagnetic radiation field propagates independently of the accelerated charge, carrying away momentum and energy. The energy in the radiation is provided by the work that accelerates the charge. We understand a photon to be the quantum of the electromagnetic radiation field, but the radiation field is a classical concept.

Coulomb field. This radiation electric field has an accompanying magnetic field, and the whole oscillating electromagnetic radiation field propagates independently of the accelerated charge, carrying away momentum and energy. The energy in the radiation is provided by the work that accelerates the charge. We understand a photon to be the quantum of the electromagnetic radiation field, but the radiation field is a classical concept.The theory of general relativity is built on the principle of the equivalence of gravitation and inertia. This means that it is impossible to distinguish through any local measurement whether one is in a gravitational field or being accelerated. An elevator out in deep space, far from any planet, could mimic a gravitational field to its occupants if it could be accelerated continuously "upward". Whether the acceleration is from motion or from gravity makes no difference in the laws of physics. This can also be understood in terms of the equivalence of so-called gravitational mass and inertial mass. The mass in Newton's law of gravity (gravitational mass) is the same as the mass in Newton's second law of motion (inertial mass). They cancel out when equated, with the result discovered by Galileo that all bodies fall at the same rate in a gravitational field, independent of their mass. This was famously demonstrated on the Moon during the Apollo 15 mission, when a hammer and a feather were dropped at the same time and, of course, struck the surface at the same time.

Closely tied in with this equivalence is the fact that gravity vanishes in free fall. For objects falling in an elevator whose cable is cut, all gravitational forces vanish, and things begin to look like the free-floating absence of forces one sees in videos from the International Space Station. One can find the weightlessness of outer space right here on earth: just jump out of an airplane. It is a lynchpin of general relativity that everything must fall together in free fall. Just as with acceleration versus gravity, no experiment should be able to distinguish the effects of free fall in a gravitational field, and being out in deep space far from any forces.

Statement of the Paradox

Putting together these two basic facts of general relativity and electrodynamics, we seem to encounter a paradox. For if we dropped a neutral particle and a charged particle together in a gravitational field, the charged particle should begin to radiate as it is accelerated under gravity, thereby losing energy, and slowing relative to the neutral particle. Then a free-falling observer could distinguish free fall from true absence of forces, because a charged particle in a free-falling laboratory would begin to be pulled relative to the neutral parts of the laboratory, even though no obvious electric fields were present.Equivalently, we can think about a charged particle at rest in a laboratory on the surface of the earth. Since we know the earth's gravitational field of 1 g is equivalent to being accelerated constantly upward at 1 g, and we know a charged particle accelerated upward at 1 g would radiate, why don't we see radiation from charged particles at rest in the laboratory? It would seem that we could distinguish between a gravitational field and acceleration, because an electric charge apparently only radiates when it is being accelerated through motion, but not through gravitation.

Resolution of the Paradox

The resolution of this paradox, like the twin paradox and ladder paradox, comes through appropriate care in distinguishing frames of reference. We follow the excellent development of Rohrlich (1965),[1] section 8-3, who shows that a charged particle and a neutral particle fall equally fast in a gravitational field, despite the fact that the charged one loses energy by radiation. Likewise, a charged particle at rest in a gravitational field does not radiate in its rest frame. The equivalence principle is preserved for charged particles.The key is to realize that the laws of electrodynamics, the Maxwell equations, hold only in an inertial frame. That is, in a frame in which no forces act locally. This could be free fall under gravity, or far in space away from any forces. The surface of the earth is not an inertial frame. It is being constantly accelerated. We know the surface of the earth is not an inertial frame because an object at rest there may not remain at rest—objects at rest fall to the ground when released. So we cannot naively formulate expectations based on the Maxwell equations in this frame. It is remarkable that we now understand the special-relativistic Maxwell equations do not hold, strictly speaking, on the surface of the earth—even though they were of course discovered in electrical and magnetic experiments conducted in laboratories on the surface of the earth. Nevertheless, in this case we cannot apply the Maxwell equations to the description of a falling charge relative to a "supported", non-inertial observer.

The Maxwell equations can be applied relative to an observer in free fall, because free-fall is an inertial frame. So the starting point of considerations is to work in the free-fall frame in a gravitational field—a "falling" observer. In the free-fall frame the Maxwell equations have their usual, flat spacetime form for the falling observer. In this frame, the electric and magnetic fields of the charge are simple: the falling electric field is just the Coulomb field of a charge at rest, and the magnetic field is zero. As an aside, note that we are building in the equivalence principle from the start, including the assumption that a charged particle falls equally as fast as a neutral particle. Let us see if any contradictions arise.

Now we are in a position to establish what an observer at rest in a gravitational field, the supported observer, will see. Given the electric and magnetic fields in the falling frame, we merely have to transform those fields into the frame of the supported observer. This is not a Lorentz transformation, because the two frames have a relative acceleration. Instead we must bring to bear the machinery of general relativity.

In this case our gravitational field is fictitious because it can be transformed away in an accelerating frame. Unlike the total gravitational field of the earth, here we are assuming that spacetime is locally flat, so that the curvature tensor vanishes. Equivalently, the lines of gravitational acceleration are everywhere parallel, with no convergences measurable in the laboratory. Then the most general static, flat-space, cylindrical metric and line element can be written:

is the speed of light,

is the speed of light,  is proper time,

is proper time,  are the usual coordinates of space and time,

are the usual coordinates of space and time,  is the acceleration of the gravitational field, and

is the acceleration of the gravitational field, and  is an arbitrary function of the coordinate but must approach the observed Newtonian value of

is an arbitrary function of the coordinate but must approach the observed Newtonian value of  . This is the metric for the gravitational field measured by the supported observer.

. This is the metric for the gravitational field measured by the supported observer.Meanwhile, the metric in the frame of the falling observer is simply the Minkowski metric:

So a falling charge will appear to radiate to a supported observer, as expected. What about a supported charge, then? Does it not radiate due to the equivalence principle? To answer this question, start again in the falling frame.

In the falling frame, the supported charge appears to be accelerated uniformly upward. The case of constant acceleration of a charge is treated by Rohrlich [1] in section 5-3. He finds a charge

uniformly accelerated at rate

uniformly accelerated at rate  has a radiation rate given by the Lorentz invariant:

has a radiation rate given by the Lorentz invariant: .

.The radiation from the supported charge is something of a curiosity: where does it go? Boulware (1980) [2] finds that the radiation goes into a region of spacetime inaccessible to the co-accelerating, supported observer. In effect, a uniformly accelerated observer has an event horizon, and there are regions of spacetime inaccessible to this observer. de Almeida and Saa (2006) [3] have a more-accessible treatment of the event horizon of the accelerated observer.