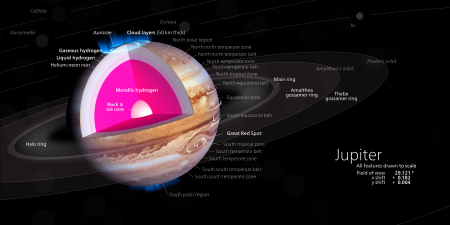

Gas giants such as Jupiter (pictured above) and Saturn might contain large amounts of metallic hydrogen (depicted in grey) and metallic helium.[1]

A diagram of Jupiter showing a model of the planet's interior, with a rocky core overlaid by a deep layer of liquid metallic hydrogen and an outer layer predominantly of molecular hydrogen.

Jupiter's true interior composition is uncertain. For instance, the

core may have shrunk as convection currents of hot liquid metallic

hydrogen mixed with the molten core and carried its contents to higher

levels in the planetary interior. Furthermore, there is no clear

physical boundary between the hydrogen layers—with increasing depth the

gas increases smoothly in temperature and density, ultimately becoming

liquid. Features are shown to scale except for the aurorae and the

orbits of the Galilean moons.

Metallic hydrogen is a kind of degenerate matter, a phase of hydrogen in which it behaves like an electrical conductor. This phase was predicted in 1935 on theoretical grounds by Eugene Wigner and Hillard Bell Huntington.[2]

At high pressure and temperatures, metallic hydrogen might exist as a liquid rather than a solid, and researchers think it is present in large quantities in the hot and gravitationally compressed interiors of Jupiter, Saturn, and in some extrasolar planets.[3]

In October 2016, there were claims that metallic hydrogen had been observed in the laboratory at a pressure of around 495 gigapascals (4,950,000 bar; 4,890,000 atm; 71,800,000 psi).[4] In January 2017, scientists at Harvard University reported the first creation of metallic hydrogen in a laboratory, using a diamond anvil cell.[5] Several researchers in the field doubt this claim.[6] Some observations consistent with metallic behavior had been reported earlier, such as the observation of new phases of solid hydrogen under static conditions[7][8] and, in dense liquid deuterium, electrical insulator-to-conductor transitions associated with an increase in optical reflectivity.[9]

Theoretical predictions

Metallization of hydrogen under pressure

Though often placed at the top of the alkali metal column in the periodic table, hydrogen does not, under ordinary conditions, exhibit the properties of an alkali metal. Instead, it forms diatomic H2 molecules, analogous to halogens and non-metals in the second row of the periodic table, such as nitrogen and oxygen. Diatomic hydrogen is a gas that, at atmospheric pressure, liquefies and solidifies only at very low temperature (20 degrees and 14 degrees above absolute zero, respectively). Eugene Wigner and Hillard Bell Huntington predicted that under an immense pressure of around 25 GPa (250000 atm; 3600000 psi) hydrogen would display metallic properties: instead of discrete H2 molecules (which consist of two electrons bound between two protons), a bulk phase would form with a solid lattice of protons and the electrons delocalized throughout.[2] Since then, producing metallic hydrogen in the laboratory has been described as "...the holy grail of high-pressure physics."[10]The initial prediction about the amount of pressure needed was eventually shown to be too low.[11] Since the first work by Wigner and Huntington, the more modern theoretical calculations were pointing toward higher but nonetheless potentially accessible metallization pressures of 100 GPa and higher.

Liquid metallic hydrogen

Helium-4 is a liquid at normal pressure near absolute zero, a consequence of its high zero-point energy (ZPE). The ZPE of protons in a dense state is also high, and a decline in the ordering energy (relative to the ZPE) is expected at high pressures. Arguments have been advanced by Neil Ashcroft and others that there is a melting point maximum in compressed hydrogen, but also that there might be a range of densities, at pressures around 400 GPa (3,900,000 atm), where hydrogen would be a liquid metal, even at low temperatures.[12][13]Superconductivity

In 1968, Neil Ashcroft suggested that metallic hydrogen might be a superconductor, up to room temperature (290 K or 17 °C), far higher than any other known candidate material. This hypothesis is based on an expected strong coupling between conduction electrons and lattice vibrations.[14]Possibility of novel types of quantum fluid

Presently known "super" states of matter are superconductors, superfluid liquids and gases, and supersolids. Egor Babaev predicted that if hydrogen and deuterium have liquid metallic states, they might have quantum ordered states that cannot be classified as superconducting or superfluid in the usual sense. Instead, they might represent two possible novel types of quantum fluids: superconducting superfluids and metallic superfluids. Such fluids were predicted to have highly unusual reactions to external magnetic fields and rotations, which might provide a means for experimental verification of Babaev's predictions. It has also been suggested that, under the influence of magnetic field, hydrogen might exhibit phase transitions from superconductivity to superfluidity and vice versa.[15][16][17]Lithium alloying reduces requisite pressure

In 2009, Zurek et al. predicted that the alloy LiH6 would be a stable metal at only one quarter of the pressure required to metallize hydrogen, and that similar effects should hold for alloys of type LiHn and possibly other related alloys of type Lin.[18]Experimental pursuit

Shock-wave compression, 1996

In March 1996, a group of scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory reported that they had serendipitously produced the first identifiably metallic hydrogen[19] for about a microsecond at temperatures of thousands of kelvins, pressures of over 1000000 atm (100 GPa), and densities of approximately 0.6 g/cm3.[20] The team did not expect to produce metallic hydrogen, as it was not using solid hydrogen, thought to be necessary, and was working at temperatures above those specified by metallization theory. Previous studies in which solid hydrogen was compressed inside diamond anvils to pressures of up to 2500000 atm (250 GPa), did not confirm detectable metallization. The team had sought simply to measure the less extreme electrical conductivity changes they expected. The researchers used a 1960s-era light-gas gun, originally employed in guided missile studies, to shoot an impactor plate into a sealed container containing a half-millimeter thick sample of liquid hydrogen. The liquid hydrogen was in contact with wires leading to a device measuring electrical resistance. The scientists found that, as pressure rose to 1400000 atm (140 GPa), the electronic energy band gap, a measure of electrical resistance, fell to almost zero. The band-gap of hydrogen in its uncompressed state is about 15 eV, making it an insulator but, as the pressure increases significantly, the band-gap gradually fell to 0.3 eV. Because the thermal energy of the fluid (the temperature became about 3000 K or 2730 °C due to compression of the sample) was above 0.3 eV, the hydrogen might be considered metallic.Other experimental research, 1996–2004

Many experiments are continuing in the production of metallic hydrogen in laboratory conditions at static compression and low temperature. Arthur Ruoff and Chandrabhas Narayana from Cornell University in 1998,[21] and later Paul Loubeyre and René LeToullec from Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique, France in 2002, have shown that at pressures close to those at the center of the Earth (3200000–3400000 atm or 320–340 GPa) and temperatures of 100–300 K (−173–27 °C), hydrogen is still not a true alkali metal, because of the non-zero band gap. The quest to see metallic hydrogen in laboratory at low temperature and static compression continues. Studies are also ongoing on deuterium.[22] Shahriar Badiei and Leif Holmlid from the University of Gothenburg have shown in 2004 that condensed metallic states made of excited hydrogen atoms (Rydberg matter) are effective promoters to metallic hydrogen.[23]Pulsed laser heating experiment, 2008

The theoretically predicted maximum of the melting curve (the prerequisite for the liquid metallic hydrogen) was discovered by Shanti Deemyad and Isaac F. Silvera by using pulsed laser heating.[24] Hydrogen-rich molecular silane (SiH4) was claimed to be metallized and become superconducting by M.I. Eremets et al..[25] This claim is disputed, and their results have not been repeated.[26][27]Observation of liquid metallic hydrogen, 2011

In 2011 Eremets and Troyan reported observing the liquid metallic state of hydrogen and deuterium at static pressures of 2600000–3000000 atm (260–300 GPa).[7] This claim was questioned by other researchers in 2012.[28][29]Z machine, 2015

In 2015, scientists at the Z Pulsed Power Facility announced the creation of metallic deuterium.[30]Claimed observation of solid metallic hydrogen, 2016

On October 5, 2016, Ranga Dias and Isaac F. Silvera of Harvard University released claims of experimental evidence that solid metallic hydrogen had been synthesised in the laboratory. This manuscript was available in October 2016,[31] and a revised version was subsequently published in the journal Science in January 2017.[4][5]In the preprint version of the paper, Dias and Silvera writes:

With increasing pressure we observe changes in the sample, going from transparent, to black, to a reflective metal, the latter studied at a pressure of 495 GPa... the reflectance using a Drude free electron model to determine the plasma frequency of 30.1 eV at T = 5.5 K, with a corresponding electron carrier density of 6.7×1023 particles/cm3, consistent with theoretical estimates. The properties are those of a metal. Solid metallic hydrogen has been produced in the laboratory.Silvera stated that they did not repeat their experiment, since more tests could damage or destroy their existing sample, but assured the scientific community that more tests are coming.[32][6] He also stated that the pressure would eventually be released, in order to find out whether the sample was metastable (i.e., whether it would persist in its metallic state even after the pressure was released).[33]

— Dias & Silvera (2016) [31]

Shortly after the claim was published in Science, Nature's news division published an article stating that some other physicists regarded the result with skepticism. Recently, prominent members of the high pressure research community have criticised the claimed results,[34][35][36] questioning the claimed pressures or the presence of metallic hydrogen at the pressures claimed.

In February 2017, it was reported that the sample of claimed metallic hydrogen was lost, after the diamond anvils it was contained between broke.[37]

In August 2017, Silvera and Dias issued an erratum[38] to the Science article, regarding corrected reflectance values due to variations between the optical density of stressed natural diamonds and the synthetic diamonds used in their pre-compression diamond anvil cell.