Robots are only as racist as we design them to be.

As the Trump administration continues to advance its hardline stance towards immigration, legal or otherwise, businesses are increasingly turning to automation and robotics to fill jobs previously held by humans. However, these thinking machines are not without drawbacks. AI development has long been beset by issues of intrinsic training bias, if not outright racist and xenophobic behavior. Take Microsoft's aborted social media bots Tay and Zo, for example, or Amazon's questionably-designed facial recognition system. However this relationship is not unidirectional -- AI can impact the expression of xenophobic ideas just as xenophobic practices can impact the rate of AI development. Which begs the question, how can we decouple the benefits that AI promises to provide from the negative consequences we're already witnessing?

The relationship between AI development and xenophobia is a complicated one, to be sure. On one hand, AI's impacts on xenophobia are themselves a mixed bag in that AI can just as readily be deployed to identify and fight xenophobic elements online as it can be used to amplify and defend them. On the other hand, xenophobic attitudes (especially when combined with strict immigration laws) can impact the speed at which AI systems are developed and deployed.

AI's track record in fighting online racism and xenophobia has been mixed at best. It's not just Tay and Zo, content surfacing algorithms from both Facebook and Twitter have helped usher in the era of fake news while deep learning systems have granted online trolls the ability to generate "deep fake" revenge porn. Conversely, the United Nations has been working since 2015 to develop machine learning capabilities that can identify and analyze xenophobic tweets during major events such as terrorist incidents or refugee crises to gauge global attitudes towards the peoples involved.

Even in the US justice system, automated systems from racist facial recognition tools to Wisconsin's indecipherable Compas sentencing algorithm appear to suffer from intrinsic training bias. That's not to say every AI developed for the judicial system is afflicted as the previous examples. IBM recently loaned out its Watson AI to help the Montgomery County Juvenile Court surface the most relevant information regarding a child's home life and social structure in an effort to provide them the best possible care.

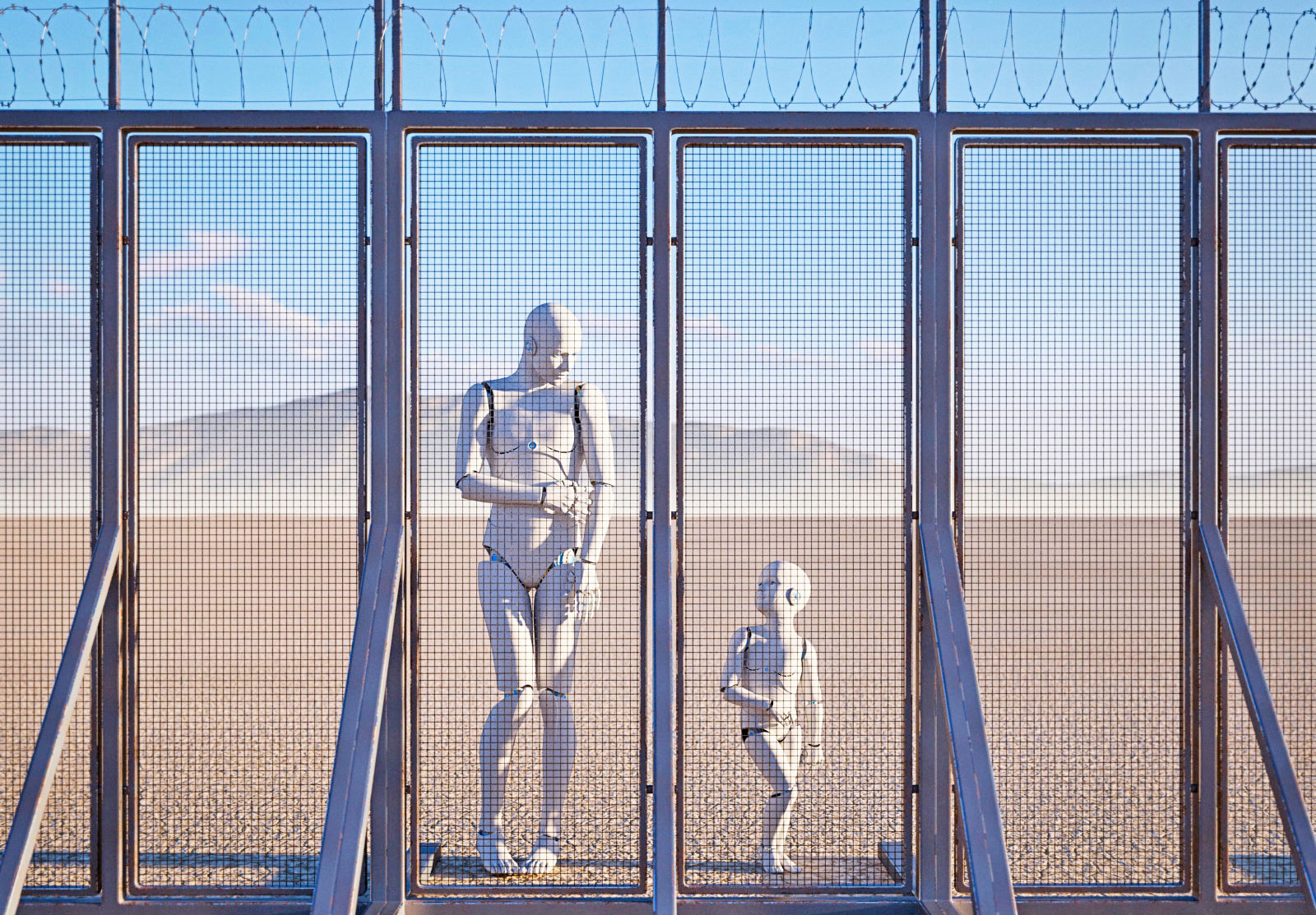

In some cases, AI can even be utilized to actively reinforce existing racist or xenophobic dogma. Just look at the "virtual border wall" prototype developed by Anduril Industries, the company started by former Oculus founder, Palmer Luckey. Using a variety of sensors, cameras and machine learning, the "Lattice" technology that drives the virtual wall can spot and identify moving objects at a distance. If that object happens to be a person crossing the US border, the system will alert the authorities. Andruil Industries hopes to eventually sell its technology to the American government to help facilitate the Trump administration's handling of refugees crossing into the US.

"I predict that in the next year or two the issue [of racial bias] is only going to continue to increase in importance," Arvind Narayanan, an assistant professor of computer science at Princeton and data privacy expert, told Engadget in 2017. "What has changed is the realization that these aren't specific exceptions of racial and gender bias. It's almost definitional that machine learning is going to pick up and perhaps amplify existing human biases. The issues are inescapable."

At the same time, xenophobia can impact the development of AI and not just through the standard issues of learning bias or fears that AI is going to put a majority of humans out of work, resulting in widespread economic anxiety.

"We live in a world where the friction of xenophobia or the friction of anti-immigration policies actually can lead to technological advancements in an odd way," Illah Nourbakhsh, Professor of Ethics and Computational Technologies at Carnegie Mellon University, told Engadget in July.

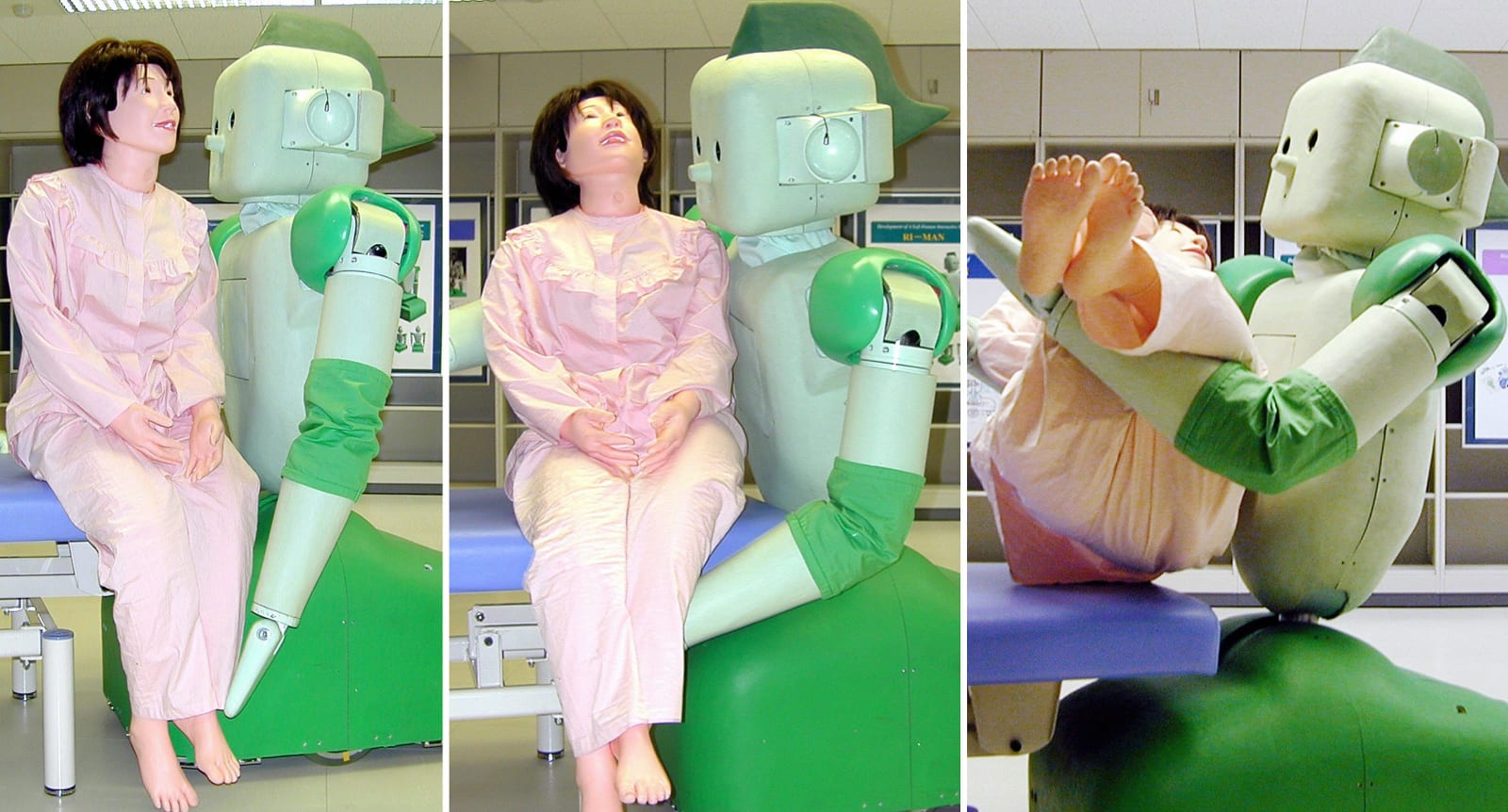

He points to Japan as an example. The island nation has famously strict immigration laws, as well as stringent licensing exams for roles in the healthcare and home care industries. This includes a six-month course in Japanese language and culture before applicants even step foot on Japanese soil. It also has a rapidly aging population -- in fact, by 2025 virtually all of Japan's baby boomers (those born between 1947 and 1949) will be 75 years of age or older. Currently there are only around 1.8 million qualified care workers currently living in Japan. The country would need to add at least 385,000 more such positions by the middle of the next decade to account for the increase in geriatric patients.

This combination of high demand and low supply, Nourbakhsh argues, should theoretically lead to a relaxing of licensing requirements or increases in foreign work permits. Instead, the Japanese have adopted a different tact.

"What they're doing to try and solve that problem in many cases is put literally hundreds of millions of dollars into the development of robotics," Nourbakhsh said. Because of restrictive immigration policies, "it becomes economically feasible to spend a huge amount of money trying to develop robots to do something that humans are actually really good at doing."

"The sidebar challenge of that is that the very technology we're trying to develop can actually distance the people that we're trying to care for from social interactions," he continued. "And we all know that social interaction is one of the things that increases the quality of life [of elderly patients] the most." Lucky for them, Sony has just released its latest iteration of the AIBO.

We're seeing a similar effect here in the US due to the current administration's hardline stance against all forms of immigration and its aggressive deportation policies targeting migrant farm workers. Agricultural companies are pouring money into automation to offset their losses of human labor.

"Agriculture is indeed the industry where it is most clear that restrictions on immigration lead to the development and adoption of mechanization," Dr. Jennifer Hunt, a professor of economics at Rutgers University, wrote to Engadget. "Michael Clemens and Ethan Lewis show that the end of the guest worker Bracero program did not raise the wages of native agricultural workers, and further show that the cause seems to be a turn to mechanization when the program ended."

Even highly skilled workers, those in the US on H-1B visas, have not proven themselves immune to the effects, despite the benefit that they provide. "My own research finds that immigrants with college or more education [apply for and receive patents] at twice the rate of natives," Hunt argued. "And that this does not come at the expense of native patenting. So immigrants increasing US patenting, and patenting has been shown to increase the US economic growth per capita, making Americans better off."