|

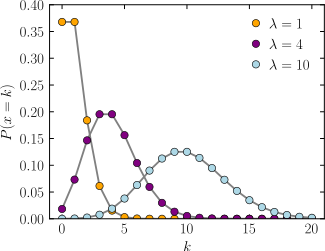

Probability mass function

The horizontal axis is the index k, the number of occurrences. λ is the expected number of occurrences. The vertical axis is the probability of k occurrences given λ. The function is defined only at integer values of k. The connecting lines are only guides for the eye. | |||||

|

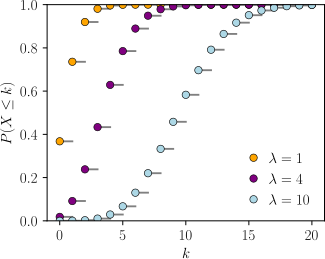

Cumulative distribution function

The horizontal axis is the index k, the number of occurrences. The CDF is discontinuous at the integers of k and flat everywhere else because a variable that is Poisson distributed takes on only integer values. | |||||

| Parameters | λ > 0 (real) — rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support |

| ||||

| pmf |

| ||||

| CDF |

, or , or  , or , or

(for  , where , where  is the upper incomplete gamma function, is the upper incomplete gamma function,  is the floor function, and Q is the regularized gamma function) is the floor function, and Q is the regularized gamma function) | ||||

| Mean |

| ||||

| Median |

| ||||

| Mode |

| ||||

| Variance |

| ||||

| Skewness |

| ||||

| Ex. kurtosis |

| ||||

| Entropy |

![\lambda [1-\log(\lambda )]+e^{-\lambda }\sum _{k=0}^{\infty }{\frac {\lambda ^{k}\log(k!)}{k!}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cf6cf37058d59e89453fd5bf9a1ece59a8c81d1a) (for large

(for large  ) )

| ||||

| MGF |

| ||||

| CF |

| ||||

| PGF |

| ||||

| Fisher information |

| ||||

In probability theory and statistics, the Poisson distribution (French pronunciation: [pwasɔ̃]; in English often rendered /ˈpwɑːsɒn/), named after French mathematician Siméon Denis Poisson, is a discrete probability distribution that expresses the probability of a given number of events occurring in a fixed interval of time or space if these events occur with a known constant rate and independently of the time since the last event. The Poisson distribution can also be used for the number of events in other specified intervals such as distance, area or volume.

For instance, an individual keeping track of the amount of mail they receive each day may notice that they receive an average number of 4 letters per day. If receiving any particular piece of mail does not affect the arrival times of future pieces of mail, i.e., if pieces of mail from a wide range of sources arrive independently of one another, then a reasonable assumption is that the number of pieces of mail received in a day obeys a Poisson distribution. Other examples that may follow a Poisson include the number of phone calls received by a call center per hour and the number of decay events per second from a radioactive source.

Basics

Example

The Poisson distribution may be useful to model events such as- The number of meteorites greater than 1 meter diameter that strike Earth in a year

- The number of patients arriving in an emergency room between 10 and 11 pm

- In a laser the number of photons hitting a detector in a particular time interval will follow Poisson distribution.

Assumptions: When is the Poisson distribution an appropriate model?

The Poisson distribution is an appropriate model if the following assumptions are true.- k is the number of times an event occurs in an interval and k can take values 0, 1, 2, ….

- The occurrence of one event does not affect the probability that a second event will occur. That is, events occur independently.

- The rate at which events occur is constant. The rate cannot be higher in some intervals and lower in other intervals.

- Two events cannot occur at exactly the same instant; instead, at each very small sub-interval exactly one event either occurs or does not occur.

- Or

- The actual probability distribution is given by a binomial distribution and the number of trials is sufficiently bigger than the number of successes one is asking about.

Probability of events for a Poisson distribution

An event can occur 0, 1, 2, … times in an interval. The average number of events in an interval is designated (lambda). Lambda is the event rate, also called the rate parameter. The probability of observing k events in an interval is given by the equation

(lambda). Lambda is the event rate, also called the rate parameter. The probability of observing k events in an interval is given by the equation

is the average number of events per interval

- e is the number 2.71828... (Euler's number) the base of the natural logarithms

- k takes values 0, 1, 2, …

- k! = k × (k − 1) × (k − 2) × … × 2 × 1 is the factorial of k.

Notice that this equation can be adapted if, instead of the average number of events

, we are given a time rate

, we are given a time rate  for the events to happen. Then

for the events to happen. Then  (with

(with  in units of 1/time), and

in units of 1/time), and

Examples of probability for Poisson distributions

On a particular river, overflow floods occur once every 100 years on average. Calculate the probability of k = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 overflow floods in a 100-year interval, assuming the Poisson model is appropriate.Because the average event rate is one overflow flood per 100 years, λ = 1

| k | P(k overflow floods in 100 years) |

|---|

| 0 | 0.368 |

| 1 | 0.368 |

| 2 | 0.184 |

| 3 | 0.061 |

| 4 | 0.015 |

| 5 | 0.003 |

| 6 | 0.0005 |

Ugarte and colleagues report that the average number of goals in a World Cup soccer match is approximately 2.5 and the Poisson model is appropriate.[3]

Because the average event rate is 2.5 goals per match, λ = 2.5.

| k | P(k goals in a World Cup soccer match) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.082 |

| 1 | 0.205 |

| 2 | 0.257 |

| 3 | 0.213 |

| 4 | 0.133 |

| 5 | 0.067 |

| 6 | 0.028 |

| 7 | 0.010 |

Once in an interval events: The special case of λ = 1 and k = 0

Suppose that astronomers estimate that large meteorites (above a certain size) hit the earth on average once every 100 years (λ = 1 event per 100 years), and that the number of meteorite hits follows a Poisson distribution. What is the probability of k = 0 meteorite hits in the next 100 years?In general, if an event occurs on average once per interval (λ = 1), and the events follow a Poisson distribution, then P(0 events in next interval) = 0.37. In addition, P(exactly one event in next interval) = 0.37, as shown in the table for overflow floods.

Examples that violate the Poisson assumptions

The number of students who arrive at the student union per minute will likely not follow a Poisson distribution, because the rate is not constant (low rate during class time, high rate between class times) and the arrivals of individual students are not independent (students tend to come in groups).The number of magnitude 5 earthquakes per year in a country may not follow a Poisson distribution if one large earthquake increases the probability of aftershocks of similar magnitude.

Among patients admitted to the intensive care unit of a hospital, the number of days that the patients spend in the ICU is not Poisson distributed because the number of days cannot be zero. The distribution may be modeled using a Zero-truncated Poisson distribution.

Count distributions in which the number of intervals with zero events is higher than predicted by a Poisson model may be modeled using a Zero-inflated model.

Poisson regression and negative binomial regression

Poisson regression and negative binomial regression are useful for analyses where the dependent (response) variable is the count (0, 1, 2, …) of the number of events or occurrences in an interval.History

The distribution was first introduced by Siméon Denis Poisson (1781–1840) and published, together with his probability theory, in 1837 in his work Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et en matière civile ("Research on the Probability of Judgments in Criminal and Civil Matters"). The work theorized about the number of wrongful convictions in a given country by focusing on certain random variables N that count, among other things, the number of discrete occurrences (sometimes called "events" or "arrivals") that take place during a time-interval of given length. The result had been given previously by Abraham de Moivre (1711) in De Mensura Sortis seu; de Probabilitate Eventuum in Ludis a Casu Fortuito Pendentibus in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, p. 219. This makes it an example of Stigler's law and it has prompted some authors to argue that the Poisson distribution should bear the name of de Moivre.A practical application of this distribution was made by Ladislaus Bortkiewicz in 1898 when he was given the task of investigating the number of soldiers in the Prussian army killed accidentally by horse kicks; this experiment introduced the Poisson distribution to the field of reliability engineering.

Definition

A discrete random variable X is said to have a Poisson distribution with parameter λ > 0, if, for k = 0, 1, 2, ..., the probability mass function of X is given by:- e is Euler's number (e = 2.71828...)

- k! is the factorial of k.

The conventional definition of the Poisson distribution contains two terms that can easily overflow on computers: λk and k!. The fraction of λk to k! can also produce a rounding error that is very large compared to e−λ, and therefore give an erroneous result. For numerical stability the Poisson probability mass function should therefore be evaluated as

lgamma function in the C (programming language) standard library (C99 version), the gammaln function in MATLAB or SciPy, or the log_gamma function in Fortran 2008 and later.

Properties

Descriptive statistics

- The expected value and variance of a Poisson-distributed random variable are both equal to λ.

- The coefficient of variation is

, while the index of dispersion is 1.

- The mean absolute deviation about the mean is

- The mode of a Poisson-distributed random variable with non-integer λ is equal to

, which is the largest integer less than or equal to λ. This is also written as floor(λ). When λ is a positive integer, the modes are λ and λ − 1.

- All of the cumulants of the Poisson distribution are equal to the expected value λ. The nth factorial moment of the Poisson distribution is λn.

- The expected value of a Poisson process is sometimes decomposed into the product of intensity and exposure (or more generally expressed as the integral of an "intensity function" over time or space, sometimes described as “exposure”).

Median

Bounds for the median (ν) of the distribution are known and are sharp:Higher moments

- The higher moments mk of the Poisson distribution about the origin are Touchard polynomials in λ:

- where the {braces} denote Stirling numbers of the second kind. The coefficients of the polynomials have a combinatorial meaning. In fact, when the expected value of the Poisson distribution is 1, then Dobinski's formula says that the nth moment equals the number of partitions of a set of size n.

Sums of Poisson-distributed random variables

- If

are independent, and

, then

. A converse is Raikov's theorem, which says that if the sum of two independent random variables is Poisson-distributed, then so are each of those two independent random variables.

Other properties

- The Poisson distributions are infinitely divisible probability distributions.

- The directed Kullback–Leibler divergence of Pois(λ0) from Pois(λ) is given by

- Bounds for the tail probabilities of a Poisson random variable

can be derived using a Chernoff bound argument.

-

,

Poisson races

Let and

and  be independent random variables, with

be independent random variables, with  , then we have that

, then we have that

The lower bound can be proved by noting that

is the probability that

is the probability that  , where

, where  , which is bounded below by

, which is bounded below by  , where

, where  is relative entropy. Further noting that

is relative entropy. Further noting that  , and computing a lower bound on the unconditional probability gives the result. More details can be found in the appendix of.

, and computing a lower bound on the unconditional probability gives the result. More details can be found in the appendix of.

Related distributions

- If

and

are independent, then the difference

follows a Skellam distribution.

- If

and

are independent, then the distribution of

conditional on

is a binomial distribution.

- Specifically, given

,

.

- More generally, if X1, X2,..., Xn are independent Poisson random variables with parameters λ1, λ2,..., λn then

- given

. In fact,

.

- given

- If

and the distribution of

, conditional on X = k, is a binomial distribution,

, then the distribution of Y follows a Poisson distribution

. In fact, if

, conditional on X = k, follows a multinomial distribution,

, then each

follows an independent Poisson distribution

.

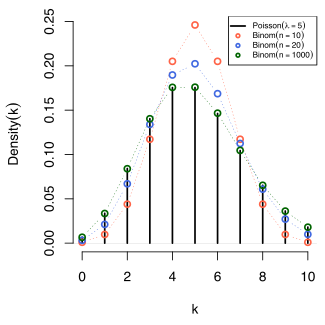

- The Poisson distribution can be derived as a limiting case to the binomial distribution as the number of trials goes to infinity and the expected number of successes remains fixed. Therefore, it can be used as an approximation of the binomial distribution if n is sufficiently large and p is sufficiently small. There is a rule of thumb stating that the Poisson distribution is a good approximation of the binomial distribution if n is at least 20 and p is smaller than or equal to 0.05, and an excellent approximation if n ≥ 100 and np ≤ 10.

- The Poisson distribution is a special case of the discrete compound Poisson distribution (or stuttering Poisson distribution) with only a parameter. The discrete compound Poisson distribution can be deduced from the limiting distribution of univariate multinomial distribution. It is also a special case of a compound Poisson distribution.

- For sufficiently large values of λ, (say λ>1000), the normal distribution with mean λ and variance λ (standard deviation

) is an excellent approximation to the Poisson distribution. If λ is greater than about 10, then the normal distribution is a good approximation if an appropriate continuity correction is performed, i.e., if P(X ≤ x), where x is a non-negative integer, is replaced by P(X ≤ x + 0.5).

- Variance-stabilizing transformation: When a variable is Poisson distributed, its square root is approximately normally distributed with expected value of about

and variance of about 1/4. Under this transformation, the convergence to normality (as λ increases) is far faster than the untransformed variable. Other, slightly more complicated, variance stabilizing transformations are available, one of which is Anscombe transform.

- If for every t > 0 the number of arrivals in the time interval [0, t] follows the Poisson distribution with mean λt, then the sequence of inter-arrival times are independent and identically distributed exponential random variables having mean 1/λ.

- The cumulative distribution functions of the Poisson and chi-squared distributions are related in the following ways:

-

- and

Occurrence

Applications of the Poisson distribution can be found in many fields related to counting:- Telecommunication example: telephone calls arriving in a system.

- Astronomy example: photons arriving at a telescope.

- Chemistry example: the molar mass distribution of a living polymerization

- Biology example: the number of mutations on a strand of DNA per unit length.

- Management example: customers arriving at a counter or call centre.

- Finance and insurance example: number of losses or claims occurring in a given period of time.

- Earthquake seismology example: an asymptotic Poisson model of seismic risk for large earthquakes. (Lomnitz, 1994).

- Radioactivity example: number of decays in a given time interval in a radioactive sample.

- The number of soldiers killed by horse-kicks each year in each corps in the Prussian cavalry. This example was made famous by a book of Ladislaus Josephovich Bortkiewicz (1868–1931).

- The number of yeast cells used when brewing Guinness beer. This example was made famous by William Sealy Gosset (1876–1937).

- The number of phone calls arriving at a call centre within a minute. This example was made famous by A.K. Erlang (1878 – 1929).

- Internet traffic.

- The number of goals in sports involving two competing teams.

- The number of deaths per year in a given age group.

- The number of jumps in a stock price in a given time interval.

- Under an assumption of homogeneity, the number of times a web server is accessed per minute.

- The number of mutations in a given stretch of DNA after a certain amount of radiation.

- The proportion of cells that will be infected at a given multiplicity of infection.

- The arrival of photons on a pixel circuit at a given illumination and over a given time period.

- The targeting of V-1 flying bombs on London during World War II investigated by R. D. Clarke in 1946.

Law of rare events

Comparison of the Poisson distribution (black lines) and the binomial distribution with n = 10 (red circles), n = 20 (blue circles), n = 1000 (green circles). All distributions have a mean of 5. The horizontal axis shows the number of events k. Notice that as n

gets larger, the Poisson distribution becomes an increasingly better

approximation for the binomial distribution with the same mean.

The rate of an event is related to the probability of an event occurring in some small subinterval (of time, space or otherwise). In the case of the Poisson distribution, one assumes that there exists a small enough subinterval for which the probability of an event occurring twice is "negligible". With this assumption one can derive the Poisson distribution from the Binomial one, given only the information of expected number of total events in the whole interval. Let this total number be

. Divide the whole interval into

. Divide the whole interval into  subintervals

subintervals  of equal size, such that

of equal size, such that  >

>  (since we are interested in only very small portions of the interval

this assumption is meaningful). This means that the expected number of

events in an interval

(since we are interested in only very small portions of the interval

this assumption is meaningful). This means that the expected number of

events in an interval  for each

for each  is equal to

is equal to  . Now we assume that the occurrence of an event in the whole interval can be seen as a Bernoulli trial, where the

. Now we assume that the occurrence of an event in the whole interval can be seen as a Bernoulli trial, where the  trial corresponds to looking whether an event happens at the subinterval

trial corresponds to looking whether an event happens at the subinterval  with probability

with probability  . The expected number of total events in

. The expected number of total events in  such trials would be

such trials would be  ,

the expected number of total events in the whole interval. Hence for

each subdivision of the interval we have approximated the occurrence of

the event as a Bernoulli process of the form

,

the expected number of total events in the whole interval. Hence for

each subdivision of the interval we have approximated the occurrence of

the event as a Bernoulli process of the form  . As we have noted before we want to consider only very small subintervals. Therefore, we take the limit as

. As we have noted before we want to consider only very small subintervals. Therefore, we take the limit as  goes to infinity.

In this case the binomial distribution converges to what is known as the Poisson distribution by the Poisson limit theorem.

goes to infinity.

In this case the binomial distribution converges to what is known as the Poisson distribution by the Poisson limit theorem.In several of the above examples—such as, the number of mutations in a given sequence of DNA—the events being counted are actually the outcomes of discrete trials, and would more precisely be modelled using the binomial distribution, that is

The word law is sometimes used as a synonym of probability distribution, and convergence in law means convergence in distribution. Accordingly, the Poisson distribution is sometimes called the law of small numbers because it is the probability distribution of the number of occurrences of an event that happens rarely but has very many opportunities to happen. The Law of Small Numbers is a book by Ladislaus Bortkiewicz (Bortkevitch) about the Poisson distribution, published in 1898.

Poisson point process

The Poisson distribution arises as the number of points of a Poisson point process located in some finite region. More specifically, if D is some region space, for example Euclidean space Rd, for which |D|, the area, volume or, more generally, the Lebesgue measure of the region is finite, and if N(D) denotes the number of points in D, thenOther applications in science

In a Poisson process, the number of observed occurrences fluctuates about its mean λ with a standard deviation . These fluctuations are denoted as Poisson noise or (particularly in electronics) as shot noise.

. These fluctuations are denoted as Poisson noise or (particularly in electronics) as shot noise.The correlation of the mean and standard deviation in counting independent discrete occurrences is useful scientifically. By monitoring how the fluctuations vary with the mean signal, one can estimate the contribution of a single occurrence, even if that contribution is too small to be detected directly. For example, the charge e on an electron can be estimated by correlating the magnitude of an electric current with its shot noise. If N electrons pass a point in a given time t on the average, the mean current is

; since the current fluctuations should be of the order

; since the current fluctuations should be of the order  (i.e., the standard deviation of the Poisson process), the charge

(i.e., the standard deviation of the Poisson process), the charge  can be estimated from the ratio

can be estimated from the ratio  .

.An everyday example is the graininess that appears as photographs are enlarged; the graininess is due to Poisson fluctuations in the number of reduced silver grains, not to the individual grains themselves. By correlating the graininess with the degree of enlargement, one can estimate the contribution of an individual grain (which is otherwise too small to be seen unaided). Many other molecular applications of Poisson noise have been developed, e.g., estimating the number density of receptor molecules in a cell membrane.

Generating Poisson-distributed random variables

A simple algorithm to generate random Poisson-distributed numbers (pseudo-random number sampling) has been given by Knuth:algorithm poisson random number (Knuth):

init:

Let L ← e−λ, k ← 0 and p ← 1.

do:

k ← k + 1.

Generate uniform random number u in [0,1] and let p ← p × u.

while p > L.

return k − 1.

The complexity is linear in the returned value k, which is λ on average. There are many other algorithms to improve this. Some are given in Ahrens & Dieter, see References below. Also, for large values of λ, there may be numerical stability issues because of the term e−λ. This could be solved by a slight change to allow λ to be added into the calculation gradually:

algorithm poisson random number (Junhao, based on Knuth):

init:

Let λLeft ← λ, k ← 0 and p ← 1.

do:

k ← k + 1.

Generate uniform random number u in (0,1) and let p ← p × u.

while p < 1 and λLeft > 0:

if λLeft > STEP:

p ← p × eSTEP

λLeft ← λLeft - STEP

else:

p ← p × eλLeft

λLeft ← 0

while p > 1.

return k − 1.

The choice of STEP depends on the threshold of overflow. For double precision floating point format, the threshold is near e700, so 500 shall be a safe STEP.

Other solutions for large values of λ include rejection sampling and using Gaussian approximation.

Inverse transform sampling is simple and efficient for small values of λ, and requires only one uniform random number u per sample. Cumulative probabilities are examined in turn until one exceeds u.

algorithm Poisson generator based upon the inversion by sequential search:

init:

Let x ← 0, p ← e−λ, s ← p.

Generate uniform random number u in [0,1].

while u > s do:

x ← x + 1.

p ← p * λ / x.

s ← s + p.

return x.

"This algorithm ... requires expected time proportional to λ as λ→∞. For large λ, round-off errors proliferate, which provides us with another reason for avoiding large values of λ."

Parameter estimation

Maximum likelihood

Given a sample of n measured values ki = 0, 1, 2, ..., for i = 1, ..., n, we wish to estimate the value of the parameter λ of the Poisson population from which the sample was drawn. The maximum likelihood estimate isTo prove sufficiency we may use the factorization theorem. Consider partitioning the probability mass function of the joint Poisson distribution for the sample into two parts: one that depends solely on the sample

(called

(called  ) and one that depends on the parameter

) and one that depends on the parameter  and the sample

and the sample  only through the function

only through the function  . Then

. Then  is a sufficient statistic for

is a sufficient statistic for  .

.

, depends only on

, depends only on  . The second term,

. The second term,  , depends on the sample only through

, depends on the sample only through  . Thus,

. Thus,  is sufficient.

is sufficient.To find the parameter λ that maximizes the probability function for the Poisson population, we can use the logarithm of the likelihood function:

with respect to λ and compare it to zero:

with respect to λ and compare it to zero:

For completeness, a family of distributions is said to be complete if and only if

implies that

implies that  for all

for all  . If the individual

. If the individual  are iid

are iid  , then

, then  . Knowing the distribution we want to investigate, it is easy to see that the statistic is complete.

. Knowing the distribution we want to investigate, it is easy to see that the statistic is complete.

must be 0. This follows from the fact that none of the other terms will be 0 for all

must be 0. This follows from the fact that none of the other terms will be 0 for all  in the sum and for all possible values of

in the sum and for all possible values of  . Hence,

. Hence,  for all

for all  implies that

implies that  , and the statistic has been shown to be complete.

, and the statistic has been shown to be complete.

Confidence interval

The confidence interval for the mean of a Poisson distribution can be expressed using the relationship between the cumulative distribution functions of the Poisson and chi-squared distributions. The chi-squared distribution is itself closely related to the gamma distribution, and this leads to an alternative expression. Given an observation k from a Poisson distribution with mean μ, a confidence interval for μ with confidence level 1 – α is is the quantile function (corresponding to a lower tail area p) of the chi-squared distribution with n degrees of freedom and

is the quantile function (corresponding to a lower tail area p) of the chi-squared distribution with n degrees of freedom and  is the quantile function of a Gamma distribution with shape parameter n and scale parameter 1. This interval is 'exact' in the sense that its coverage probability is never less than the nominal 1 – α.

is the quantile function of a Gamma distribution with shape parameter n and scale parameter 1. This interval is 'exact' in the sense that its coverage probability is never less than the nominal 1 – α.When quantiles of the Gamma distribution are not available, an accurate approximation to this exact interval has been proposed (based on the Wilson–Hilferty transformation):

denotes the standard normal deviate with upper tail area α / 2.

denotes the standard normal deviate with upper tail area α / 2.

For application of these formulae in the same context as above (given a sample of n measured values ki each drawn from a Poisson distribution with mean λ), one would set

Bayesian inference

In Bayesian inference, the conjugate prior for the rate parameter λ of the Poisson distribution is the gamma distribution. Let in the limit as

in the limit as  , which follows immediately from the general expression of the mean of the gamma distribution.

, which follows immediately from the general expression of the mean of the gamma distribution.The posterior predictive distribution for a single additional observation is a negative binomial distribution, sometimes called a Gamma–Poisson distribution.

Simultaneous estimation of multiple Poisson means

Suppose is a set of independent random variables from a set of

is a set of independent random variables from a set of  Poisson distributions, each with a parameter

Poisson distributions, each with a parameter  ,

,  , and we would like to estimate these parameters. Then, Clevenson and Zidek show that under the normalized squared error loss

, and we would like to estimate these parameters. Then, Clevenson and Zidek show that under the normalized squared error loss  , when

, when  , then, similar as in Stein's famous example for the Normal means, the MLE estimator

, then, similar as in Stein's famous example for the Normal means, the MLE estimator  is inadmissible.

is inadmissible.In this case, a family of minimax estimators is given for any

and

and  as

as

Bivariate Poisson distribution

This distribution has been extended to the bivariate case. The generating function for this distribution is is to take three independent Poisson distributions

is to take three independent Poisson distributions  with means

with means  and then set

and then set  . The probability function of the bivariate Poisson distribution is

. The probability function of the bivariate Poisson distribution is

Computer software for the Poisson distribution

Poisson distribution using R

The R function dpois(x, lambda)

calculates the probability that there are x events in an interval,

where the argument "lambda" is the average number of events per

interval.

For example,

dpois(x=0, lambda=1) = 0.3678794

dpois(x=1, lambda=2.5) = 0.2052125

The following R code creates a graph of the Poisson distribution from x= 0 to 8, with lambda=2.5.

x=0:8

px = dpois(x, lambda=2.5)

plot(x, px, type="h", xlab="Number of events k",

ylab="Probability of k events", ylim=c(0,0.5), pty="s", main="Poisson

distribution \n Probability of events for lambda = 2.5")

Poisson distribution using Excel

The Excel function POISSON( x, mean, cumulative )

calculates the probability of x events where mean is lambda, the

average number of events per interval. The argument cumulative specifies

the cumulative distribution.For example,

=POISSON(0, 1, FALSE) = 0.3678794

=POISSON(1, 2.5, FALSE) = 0.2052125

Poisson distribution using Python (SciPy)

The functionscipy.stats.distributions.poisson.pmf(x, poissonLambda)

calculates the probability that there are x events in an interval,

where the argument "poissonLambda" is the average number of events per

interval.

Poisson distribution using Mathematica

Mathematica supports the univariate Poisson distribution asPoissonDistribution[ ]

], and the bivariate Poisson distribution as MultivariatePoissonDistribution[ ,{

,{  ,

,  }]

}], including computation of probabilities and expectation, sampling, parameter estimation and hypothesis testing.

![g(u,v)=\exp[(\theta _{1}-\theta _{12})(u-1)+(\theta _{2}-\theta _{12})(v-1)+\theta _{12}(uv-1)]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0d994b2c4f3b36c80cfd0b97ed72fe289c0855d4)