| Homo heidelbergensis

Temporal range: 0.8–0.1 Ma

| |

|---|---|

| |

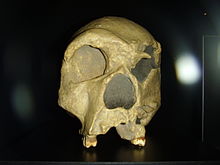

| Cranium 5 (skull with jawbone) from Sima de los Huesos (cast at Natural History Museum, London)

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. heidelbergensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Homo heidelbergensis

Schoetensack, 1908

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

† Homo rhodesiensis (Woodward, 1921) | |

Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans in the genus Homo of the Middle Pleistocene (between about 700,000 and 300,000 years ago), known from fossils found in Southern Africa, East Africa and Europe. African H. heidelbergensis is also known as Homo rhodesiensis (possibly an African subspecies, Homo heidelbergensis ssp., with an extended definition of Homo heidelbergensis understood as a polymorphic species dispersed throughout Africa and western Eurasia with a range spanning the Middle Pleistocene, c. 0.8–0.12 Mya).

The skulls of this species share features with both Homo erectus and anatomically modern Homo sapiens; its brain was nearly as large as that of Homo sapiens. The first discovery – a mandible – was made in 1908 at Mauer near Heidelberg in Germany where it was described and named by Otto Schoetensack, but the vast majority of H. heidelbergensis fossils have been found since 1996. The Sima de los Huesos cave at Atapuerca in northern Spain holds particularly rich layers of deposits where excavations were still in progress as of 2015.

H. heidelbergensis was dispersed throughout Eastern and Southern Africa (Ethiopia, Namibia, Southern Africa) as well as Europe (England, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Spain). Its exact relation both to the earlier Homo antecessor and Homo ergaster, and to the later lineages of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans is unclear.

Homo sapiens has been proposed as derived from H. heidelbergensis via Homo rhodesiensis, present in East and North Africa from around 400,000 years ago. The correct assignment of many fossils to a particular chronospecies is difficult and often differences in opinion ensue among paleoanthropologists due to the absence of universally accepted dividing lines (autapomorphies) between Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Homo rhodesiensis and Neanderthals. Homo rhodesiensis is often considered a late form of H. heidelbergensis. The taxonomy of Middle Pleistocene archaic humans remains under active revision as new evidence is evaluated.

It is uncertain whether H. heidelbergensis is ancestral to Homo sapiens, as a fossil gap in Africa between 400,000 and 260,000 years ago obscures the presumed derivation of H. sapiens from H. rhodesiensis. Genetic analysis of the Sima de los Huesos fossils (Meyer et al. 2016) seems to suggest that H. heidelbergensis in its entirety should be included in the Neanderthal lineage, as "pre-Neanderthal" or "archaic Neanderthal" or "early Neanderthal", while the divergence time between the Neanderthal and modern lineages has been pushed back to before the emergence of H. heidelbergensis, to about 600,000 to 800,000 years ago, the approximate time of disappearance of Homo antecessor.

The delineation between early H. heidelbergensis and H. erectus is also unclear.

Derivation and taxonomy

Homo heidelbergensis: Steinheim skull replica

H. heidelbergensis is thought to be derived from Homo antecessor, around 800,000 to 700,000 years ago. The oldest known fossil classified as H. heidelbergensis dates to around 600,000 years ago, but the flint tools found in 2005 at Pakefield near Lowestoft in Suffolk with teeth from the water vole Mimomys savini, a key dating species, suggest human presence in England at 700,000 years ago, assumed to correspond to a transitional form between H. antecessor and H. heidelbergensis.

In Europe, H. heidelbergensis is taken to have given rise to H. neanderthalensis at 240,000 years ago (a conventional date dictated by a fossil gap; late H. heidelbergensis in Europe prior to 240 kya is also called "pre-Neanderthal" or "ante-Neanderthal"). Homo sapiens most likely derived from H. rhodesiensis (African H. Heidelbergensis) after around 300,000 years ago.

A morphological separation of a European and an African branch of H. heidelbergensis during the Wolstonian Stage and Ipswichian Stage, the last of the prolonged Quaternary glacial periods, has been argued based on the evidence of the Atapuerca skull in Spain and the Kabwe skull in modern-day Zambia.

Neither the derivation of H. heidelbergensis from H. erectus, nor the derivation of anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals from H. heidelbergensis, are clear-cut and are the object of debate. Both H. erectus and H. heidelbergensis are described as polytypic species, which went through a number of population bottlenecks and associated In the summary of Hublin (2013), Middle Pleistocene humans in Eurasia underwent a succession of population bottlenecks due to glaciations. The "Western Eurasian clade" derived form H. rhodesiensis or H. heidelbergensis sensu lato (i.e. the Neanderthals) diverge at MIS 12 (480 kya) but coalesce as late as MIS 5 (130 kya), suggesting a division between Eurasian H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis before MIS 11 (424 kya). A fossil gap in Africa between 400 and 260 kya obscures the presumed derivation of H. sapiens from H. rhodesiensis.

Chris Stringer (2012) argues for Homo heidelbergensis as an independent chronospecies. A 2013 genetic study on the Sima de los Huesos fossils classified them as H. heidelbergensis or "early Neanderthal".

For more than half a century, many experts were reluctant to accept Homo heidelbergensis as a separate taxon due to the rarity of specimens, which prevented sufficient informative morphological comparisons and the distinction of H. heidelbergensis from other known human species. The species name "heidelbergensis" only experienced a renaissance with the many discoveries of Middle Pleistocene fossils since the 1990s.

The paleontology institute at Heidelberg University, where the type specimen is kept since 1908, as late as 2010 still classified it as Homo erectus heidelbergensis, i.e. categorizing it as a Homo erectus subspecies. This was reportedly changed to Homo heidelbergensis, accepting the categorization as separate species, in 2015.

"Rhodesian Man" (Kabwe 1) is now mostly classified as Homo heidelbergensis, though other designations such as Homo sapiens arcaicus and Homo sapiens rhodesiensis have also been proposed. White et al. (2003) suggested Rhodesian Man as ancestral to Homo sapiens idaltu (Herto Man).

Morphology

H. heidelbergensis adult male, reconstruction by Élisabeth Daynès (2010) based on fragments from Sima de los Huesos.

Homo heidelbergensis is intermediate between Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis, with a typical cranial volume of approximately 1,250 cm3 (76 cu in). "The anatomy [of H. heidelbergensis] is clearly more primitive than that of Neanderthal, but the harmoniously rounded dental arch and the complete row of teeth...already typically human."

In general, the findings show a continuation of evolutionary trends that are emerging from around the Lower into Middle Pleistocene. Along with changes in the robustness of cranial and dental features, a remarkable increase in brain size from H. erectus towards H. heidelbergensis is noticeable.

Male H. heidelbergensis averaged about 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) tall and 62 kg (136 lb). Females averaged 1.57 m (5 ft 2 in) and 51 kg (112 lb). A reconstruction of 27 complete human limb bones found in Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain) has helped to determine the height of H. heidelbergensis compared with H. neanderthalensis; the conclusion was that these H. heidelbergensis averaged about 170 cm (5 ft 7in) in height and were only slightly taller than Neanderthals. According to Lee R. Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand, numerous fossil bones indicate some populations of H. heidelbergensis were "giants" routinely over 2.13 m (7 ft) tall and inhabited South Africa between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago.

Otto Schoetensack described the mandible Mauer 1 in his original species description in 1907:

The "nature of our object" reveals itself "at first sight" since "a certain disproportion between the jaw and the teeth" is obvious: "The teeth are too small for the bone. The available space would allow for a far greater flexibility of development" and "It shows a combination of features, which has been previously found neither on a recent nor a fossil human mandible. Even the scholar should not be blamed if he would only reluctantly accept it as human: Entirely missing is the one feature, which is regarded as particularly human, namely an outer projection of the chin portion, yet this deficiency is found to be combined with extremely strange dimensions of the mandibular body. The actual proof that we are dealing with human parts here only lies within the nature of the dentition. The completely preserved teeth bear the stamp 'human' as evidence: The canines show no trace of a stronger expression in relation to the other groups of teeth. They suggest a moderate and harmonious co-evolution, as it is the case in recent humans."

Behavior

One of hundreds of handaxes found at Boxgrove.

Discoveries in a pit in Atapuerca (Spain) of 28 human skeletons suggest that H. heidelbergensis might have been the first species of the genus Homo to bury its dead.

The morphology of the outer and middle ear suggests they had an auditory sensitivity similar to modern humans. They were probably able to differentiate between many different sounds. Dental wear analysis suggests they were as likely to be right-handed as modern people. Steven Mithen believes that H. heidelbergensis, like its descendant H. neanderthalensis, acquired a pre-linguistic system of communication. No forms of art have been uncovered, although red ochre, a mineral that can be used to mix a red pigment which is useful as a paint, has been found at Terra Amata excavations in the south of France.

An archeological site in Schöningen, Germany contained eight exceptionally well-preserved ~400,000-year-old spears for hunting, and various other wooden tools. 500,000-year-old hafted stone points used for hunting are reported from Kathu Pan 1 in South Africa, tested by way of use-wear replication. This find could mean that modern humans and Neanderthals inherited the stone-tipped spear, rather than developing the technology independently.

The Schöningen Spears are eight wooden throwing spears, dated to before 300,000 years ago, discovered between 1994 and 1998 in the open-cast lignite mine, Schöningen, county Helmstedt, Germany, together with thousands of animal bones. They are regarded as the direct evidence for active hunting by H. heidelbergensis (pre-Neanderthals).

Fossils

Original type specimen from Mauer

Europe

Mauer 1, the first fossil discovery of this species, was found on 21 October 1907, at Mauer, near Heidelberg, Germany. It is a jaw in good condition except for the missing premolar teeth, which were eventually found near the jaw. Otto Schoetensack, from the University of Heidelberg, identified and named the fossil.The next H. heidelbergensis remains were found in Steinheim an der Murr, Germany (the Steinheim Skull, 350kya), Arago, France (Arago 21), Petralona, Greece, and Ciampate del Diavolo, Italy.

Boxgrove Man is the name associated with a lower tibia discovered in 1994 at the Boxgrove Quarry site, close to the English Channel. The fossil was found along with hundreds of hand axes, and has been dated between 478,000 and 524,000 years old. Several H. heidelbergensis teeth were found at the same site in subsequent seasons.

Beginning in 1992, a Spanish team has located more than 5,500 human bones dated to an age of at least 350,000 years in the Sima de los Huesos site in the Sierra de Atapuerca in northern Spain. The pit contains fossils of perhaps 32 individuals together with remains of Ursus deningeri and other carnivores and a biface nicknamed Excalibur. It is hypothesized that this Acheulean axe made of red quartzite was some kind of ritual offering for a funeral. If it is so, it would be the oldest evidence of known of funerary practices. Ninety percent of the known H. heidelbergensis remains have been obtained from this site. The fossil pit bones include:

- A complete cranium (skull 5), nicknamed Miguelón, and fragments of other crania, such as skull 4, nicknamed Agamemnón and skull 6, nicknamed Rui (from El Cid, a local hero).

- A complete pelvis (pelvis 1), nicknamed Elvis, in remembrance of Elvis Presley.

- Mandibles, teeth, and many postcranial bones (femurs, hand and foot bones, vertebrae, ribs, etc.)

There is current debate among scholars whether the remains at Sima de los Huesos are those of H. heidelbergensis or early H. neanderthalensis. In 2015, the study of mitochondrial DNA samples from three caves Sima de los Huesos revealed that they are "distantly related to the mitochondrial DNA of Denisovans rather than to that of Neanderthals."

In 2016 Nuclear DNA analysis determined the Sima hominins are Neanderthals and not Denisova hominins and the divergence between Neanderthals, Denisovans and Anatomically Modern Humans predates 430,000 years ago.

Africa

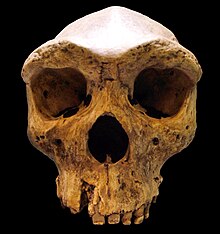

Replica of the Kabwe skull

Facial reconstruction based on the Kabwe skull by John Gurche (2010), Smithsonian Museum of Natural History

Reconstruction of Homo rhodesiensis based on the Kabwe skull, by Élisabeth Daynès (2010), Museum of Human Evolution, Burgos.

A number of morphologically-comparable fossil remains came to light in East Africa (Bodo, Ndutu, Eyasi, Ileret) and North Africa (Salé, Rabat, Dar-es-Soltane, Djbel Irhoud, Sidi Aberrahaman, Tighenif) during the 20th century. The Saldanha cranium, found in 1953 in South Africa was subject to at least three taxonomic revisions from 1955 to 1996.

Kabwe 1, also called the Broken Hill skull, was assigned by Arthur Smith Woodward in 1921 as the type specimen for Homo rhodesiensis; it is today mostly assigned to Homo heidelbergensis. It was found in a lead and zinc mine in Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia) in 1921 by Tom Zwiglaar, a Swiss miner. In addition to the cranium, an upper jaw from another individual, a sacrum, a tibia, and two femur fragments were also found. The skull was dubbed "Rhodesian Man" at the time of the find, but is now commonly referred to as the Broken Hill skull or the Kabwe cranium.

Cranial capacity of the Broken Hill skull has been estimated at 1,230 cm³. Bada, & al., (1974) published the direct date of 110 ka for this specimen measured by aspartic acid racemisation. The destruction of the paleoanthropological site has made layered dating impossible. The skull suggests an extremely robust individual with the comparatively largest brow-ridges of any known hominin. It was described as having a broad face similar to that of Homo neanderthalensis (i.e. large nasal bones and thick protruding brow ridges). Consequently, researchers came up with interpretations such as "African Neanderthal". However, with regard to the skull's extreme robustness, recent research has highlighted several intermediate features between modern Homo sapiens and Neanderthal. The skull has cavities in ten of the upper teeth and is considered one of the oldest known occurrences of cavities. Pitting indicates significant infection before death and implies that the cause of death may have been due to dental disease infection or possibly chronic ear infection. The skull is kept in the Natural History Museum, London. There is a replica in the Museum in Livingstone, Zambia.

The 600,000 year old Bodo cranium was found in 1976 by members of an expedition led by Jon Kalb at Bodo D'ar in the Awash River valley of Ethiopia. The initial discovery - a lower face - was made by Alemayhew Asfaw and Charles Smart. Two weeks later, Paul Whitehead and Craig Wood found the upper portion of the face. The skull is 600,000 years old. Although the skull is most similar to those of Kabwe, Woodward's nomenclature was discontinued and its discoverers attributed it to H. heidelbergensis. It has features, that represent a transition between Homo ergaster/erectus and Homo sapiens.

Another specimen, "the hominid from Lake Ndutu" in northern Tanzania, around 400,000 years old. In 1976 R.J.Clarke classified it as Homo erectus and it has generally been viewed as such since, although points of similarity to H. sapiens have also been recognized. After comparative studies with similar finds in Africa allocation to an African subspecies of H. sapiens seems most appropriate. An indirect cranial capacity estimate suggests 1100 ml. Its supratoral sulcus morphology and the presence of protuberance as suggested by Philip Rightmire "give the Nudutu occiput an appearance which is also unlike that of Homo erectus", but Stinger (1986) pointed out that a thickened iliac pillar is typical for Homo erectus. In a 1989 publication Clarke concludes: "It is assigned to archaic Homo sapiens on the basis of its expanded parietal and occipital regions of the brain".

The Saldanha cranium, or Elandsfontein cranium, are fossilized remains later identified as Homo heidelbergensis, found in 1954 in Elandsfontein, located in the Hopefield of South Africa.

Transitional fossils

- The "Galilee skull", found in 1925/6 at Mugharet el-Zuttiyeh, now in Israel, has been described as "the most likely Heidelberg candidate from Western Asia".

- Petralona 1, discovered in Petralona cave, Greece, in 1960, dated to between roughly 350,000 and 150,000 years old. It has been classified as either H. heidelbergensis or H. neanterthalensis.

- Tautavel Man (Arago 21) is a human skull discovered on 22 July 1971 near the village of Tautavel in Pyrénées-Orientales, dated at 450,000 years old. The fossil was classified as Homo erectus tautavelensis, and as such would not belong to H. heidelbergensis but to a different lineage of H. erectus which occupied Europe at the same time as H. heidelbergensis.