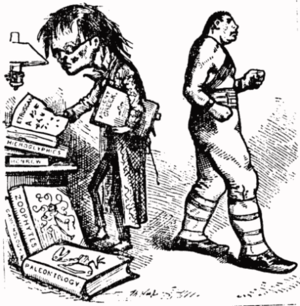

Intellectual and anti-intellectual: Political cartoonist Thomas Nast contrasts the reedy scholar with the bovine boxer, epitomizing the populist

view of reading and study as antithetical to sport and athleticism.

Note the disproportionate heads and bodies, with the size of the head

representing "mental" ability and intelligence, and the size of the body

representing kinesthetic talent and "physical" ability.

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy, and the dismissal of art, literature, and science as impractical and even contemptible human pursuits. Anti-intellectuals present themselves and are perceived as champions of common folk—populists against political and academic elitism—and tend to see educated people as a status class detached from the concerns of most people, and feel that intellectuals dominate political discourse and control higher education.

Totalitarian governments manipulate and apply anti-intellectualism to repress political dissent. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and the following fascist dictatorship (1939–1975) of General Francisco Franco, the reactionary repression of the White Terror (1936–1945) was notably anti-intellectual, with most of the 200,000 civilians killed being the Spanish intelligentsia, the politically active teachers and academics, artists and writers of the deposed Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939). In the communist state of Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979), the Khmer Rouge régime of Pol Pot condemned all of the non-communist intelligentsia to death in the Killing Fields.

Ideological anti-intellectualism

In

the "Night of the Long Batons" (29 July 1966), the federal police

physically purged politically-incorrect academics, who opposed the

right-wing military dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía (1966–70) in Argentina, from five faculties of the University of Buenos Aires.

The cultural re-organization of Cambodian society, by the dictator Pol Pot, created a government which tried to re-make its society anti-intellectual in what became known as Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979), a de-industrialized, agricultural country.

In the 20th century, societies have systematically removed

intellectuals from power, to expediently end public political dissent.

During the Cold War (1945–1991), the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (1948–1990) ostracized the philosopher Václav Havel as a politically-unreliable man unworthy of ordinary Czechs' trust; the post-communist Velvet Revolution (17 Nov.–29 Dec. 1989) elected Havel president for ten years.

In 1966, the anti-communist Argentine military dictatorship of Gen. Juan Carlos Onganía (1966–70) intervened at the University of Buenos Aires with the Night of the Long Batons to physically dislodge politically-dangerous academics from five university faculties. That expulsion to exile of the academic intelligentsia became a national brain drain upon the society and economy of Argentina. In support of the military repression of free speech, biochemist César Milstein

said, "Our country would be put in order, as soon as all the

intellectuals who were meddling in the region were expelled." In Brazil,

the government banished the educator Paulo Freire for being an ignorant man, said the organizers of the current coup d'état.

Ideologically-extreme dictatorships who mean to recreate a society, such as the Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia (1975–79), pre-emptively killed potential political opponents, especially the educated middle-class and the intelligentsia. To realize the Year Zero of Cambodian history, Khmer Rouge social engineering

restructured the economy by de-industrialization, and assassinated

non-communist Cambodians suspected of "involvement in free-market

activities", such as the urban professionals of society (physicians,

attorneys, engineers, et al.) and people with political connections to foreign governments. The Maoist doctrine of Pol Pot identified the farmers as the true proletariat of Cambodia and the true representatives of the working class entitled to hold government power, hence the anti-intellectual purges.

Anti-intellectualism is not always violent, because any social group can act anti-intellectually and discount the humanist value to their society of intellect, intellectualism, and higher education.

Academic anti-intellectualism

United States

In The Campus Wars (1971), the philosopher John Searle

said that "the two most salient traits of the radical movement are its

anti-intellectualism and its hostility to the university as an

institution. ... Intellectuals, by definition, are people who take ideas

seriously for their own sake. Whether or not a theory is true or false

is important to them, independently of any practical applications it may

have. [Intellectuals] have, as Richard Hofstadter has pointed out, an

attitude to ideas that is at once playful and pious. But, in the radical

movement, the intellectual ideal of knowledge for its own sake is

rejected. Knowledge is seen as valuable only as a basis for action, and

it is not even very valuable there. Far more important than what one

knows is how one feels."

In Social Sciences as Sorcery (1972), the sociologist Stanislav Andreski advised laymen to distrust the intellectuals' appeals to authority

when they make questionable claims about resolving the problems of

their society: "Do not be impressed by the imprint of a famous

publishing house, or the volume of an author's publications. ...

Remember that the publishers want to keep the printing presses busy, and

do not object to nonsense if it can be sold."

In Science and Relativism: Some Key Controversies in the Philosophy of Science (1990), the epistemologist Larry Laudan said that the prevailing type of philosophy taught at university in the U.S. (Postmodernism and Poststructuralism)

is anti-intellectual, because "the displacement of the idea that facts

and evidence matter, by the idea that everything boils down to

subjective interests and perspectives is — second only to American

political campaigns — the most prominent and pernicious manifestation

of anti-intellectualism in our time."

Distrust of intellectuals

In the U.S., the American conservative economist Thomas Sowell

argued for distinctions between unreasonable and reasonable wariness of

intellectuals in their influence upon the institutions of a society. In

defining intellectuals as "people whose occupations deal primarily with

ideas", they are different from people whose work is the practical

application of ideas. That cause for layman mistrust lies in the

intellectuals' incompetence outside their fields of expertise. Although

possessed of great working knowledge in their specialist fields, when

compared to other professions and occupations, the intellectuals of a

society face little discouragement against speaking authoritatively

beyond their field of formal expertise, and thus are unlikely to face

responsibility for the social and practical consequences of their

errors. Hence, a physician is judged competent by the effective

treatment of the sickness of a patient, yet might face a medical malpractice lawsuit should the treatment harm the patient. In contrast, a tenured

university professor is unlikely to be judged competent or incompetent

by the effectiveness of his or her intellectualism (ideas), and thus not

face responsibility for the social and practical consequences of the

implementation of the ideas, e.g. the Chicago Boys and the Military dictatorship of Chile (1973–90).

In the book Intellectuals and Society (2009), Sowell said that:

By encouraging, or even requiring, students to take stands where they have neither the knowledge nor the intellectual training to seriously examine complex issues, teachers promote the expression of unsubstantiated opinions, the venting of uninformed emotions, and the habit of acting on those opinions and emotions, while ignoring or dismissing opposing views, without having either the intellectual equipment or the personal experience to weigh one view against another in any serious way.

Hence, school teachers are part of the intelligentsia who

recruit children in elementary school and teach them politics—to

advocate for or to advocate against a public policy—as part of

community-service projects; which political experience later assists

them in earning admission to university. In that manner, the

intellectuals of a society intervene and participate in social arenas of

which they might not possess expert knowledge, and so unduly influence

the formulation and realization of public policy.

In the event, teaching political advocacy in elementary school

encourages students to formulate opinions "without any intellectual

training or prior knowledge of those issues, making constraints against

falsity few or non-existent."

In Britain, the anti-intellectualism of the writer Paul Johnson

derived from his close examination of twentieth-century history, which

revealed to him that intellectuals have continually championed

disastrous public policies for social welfare and public education,

and warned the layman public to "beware [the] intellectuals. Not merely

should they be kept well away from the levers of power, they should

also be objects of suspicion when they seek to offer collective advice." In that vein, "In the Land of the Rococo Marxists" (2000), the American writer Tom Wolfe characterized the intellectual as "a person knowledgeable in one field, who speaks out only in others."

17th century

In the book The Powring Out of the Seven Vials (1642), the Protestant minister John Cotton equated education and intellectualism with atheist service to the supernatural.

In The Powring Out of the Seven Vials (1642), the Puritan John Cotton demonized intellectual men and women by noting that "the more learned and witty you bee, the more fit to act for Satan will you bee. ... Take off the fond doting ... upon the learning of the Jesuits,

and the glorie of the Episcopacy, and the brave estates of the

Prelates. I say bee not deceived by these pompes, empty shewes, and

faire representations of goodly condition before the eyes of flesh and

blood, bee not taken with the applause of these persons." Yet, not every Puritan concurred with Cotton's religious contempt for secular education, some, such as John Harvard, founded a university.

In The Quest for Cosmic Justice (2001), the economist

Thomas Sowell said that anti-intellectualism in the U.S. began in the

early Colonial era, as an understandable wariness of the educated

upper-classes, because the country mostly was built by people who had

fled political and religious persecution by the social system of the

educated upper classes. Moreover, there were few intellectuals who

possessed the practical hands-on skills required to survive in the New

World of North America, which absence from society lead to a

deep-rooted, populist suspicion of men and women who specialize in "verbal virtuosity", rather than tangible, measurable products and services:

From its colonial beginnings, American society was a "decapitated" society—largely lacking the top-most social layers of European society. The highest elites and the titled aristocracies had little reason to risk their lives crossing the Atlantic, and then face the perils of pioneering. Most of the white population of colonial America arrived as indentured servants and the black population as slaves. Later waves of immigrants were disproportionately peasants and proletarians, even when they came from Western Europe ... The rise of American society to pre-eminence, as an economic, political, and military power, was thus the triumph of the common man, and a slap across the face to the presumptions of the arrogant, whether an elite of blood or books.

19th century

In U.S. history, the advocacy and acceptability of anti-intellectualism varied, because in the 19th century most people lived a rural life of manual labor

and agricultural work, therefore, an academic education in the

Græco–Roman classics, was perceived as of impractical value; the bookish

man is unprofitable. Yet, in general, Americans were a literate people who read Shakespeare

for intellectual pleasure and the Christian Bible for emotional succor;

thus, the ideal American Man was a literate and technically-skilled man

who was successful in his trade, ergo a productive member of society. Culturally, the ideal American was the self-made man whose knowledge

derived from life-experience, not an intellectual man whose knowledge of

the real world derived from books, formal education, and academic

study; thus, the justified anti-intellectualism reported in The New Purchase, or Seven and a Half Years in the Far West (1843), the Rev. Bayard R. Hall, A.M., said about frontier Indiana:

We always preferred an ignorant, bad man to a talented one, and, hence, attempts were usually made to ruin the moral character of a smart candidate; since, unhappily, smartness and wickedness were supposed to be generally coupled, and [like-wise] incompetence and goodness.

Yet, in the society of the U.S., the "real-life" redemption of the egghead intellectual was possible if he embraced the mores of mainstream society; thus, in the fiction of O. Henry,

a character noted that once an East Coast university graduate "gets

over" his intellectual vanity—he no longer thinks himself better than

other men—he makes just as good a cowboy as any other young man, despite his common-man counterpart being the slow-witted naïf of good heart, a pop culture stereotype from stage shows.

20th/21st centuries

Political

polarization in the U.S. favoured the use of anti-intellectualism by

each political party (Republican and Democratic) to undermine the

credibility of the other party with the middle class. In Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963) the historian Richard Hofstadter

said that anti-intellectualism is a social-class response, by the

middle-class "mob", against the privileges of the political élites.

As the middle class developed political power, they exercised their

belief that the ideal candidate to office was the "self-made man", not

the well-educated man born to wealth. The self-made man, from the middle

class, could be trusted to act in the best interest of his fellow

citizens. In Americans and Chinese: Passages to Differences (1980), Francis Hsu said that American egalitarianism is stronger in the U.S. than in Europe, e.g. in England,

English individualism developed hand in hand with legal equality. American self-reliance, on the other hand, has been inseparable from an insistence upon economic and social as well as political equality. The result is that a qualified individualism, with a qualified equality, has prevailed in England, but what has been considered the unalienable right of every American is unrestricted self-reliance and, at least ideally, unrestricted equality. The English, therefore, tend to respect class-based distinctions in birth, wealth, status, manners, and speech, while Americans resent them.

Such social resentment characterises contemporary political

discussions about the socio-political functions of mass-communication

media and science; that is, scientific facts, generally accepted by

educated people throughout the world, are misrepresented as opinions in

the U.S., specifically about climate science and global warming. In 1912, the New Jersey governor, Woodrow Wilson, described the battles of anti-intellectualism:

What I fear is a government of experts. God forbid that, in a democratic country, we should resign the task and give the government over to experts. What are we for if we are to be scientifically taken care of by a small number of gentlemen who are the only men who understand the job?

Miami University anthropology professor H. Sidky has argued that

21st-century anti-scientific and pseudoscientific approaches to

knowledge, particularly in the United States, are rooted in a

postmodernist "decades-long academic assault on science:" "Many of those

indoctrinated in postmodern anti-science went on to become conservative

political and religious leaders, policymakers, journalists, journal

editors, judges, lawyers, and members of city councils and school

boards. Sadly, they forgot the lofty ideals of their teachers, except

that science is bogus."

An uneducated society

American society tends to deny the factual reality of climate change (DJS -- vague). In addition, 25% of the U.S. population believes in a geocentric solar system (that the sun orbits the earth), and, in 2014, 35% of Americans could not name any branch of the U.S. government.

The U.S. is ranked 52nd out of 139 nations in quality of educational

instruction and 12th in the number of university-educated adults.

At universities, student anti-intellectualism has resulted in the

social acceptability of cheating on schoolwork, especially in the

business schools, a manifestation of ethically expedient cognitive dissonance rather than of academic critical thinking.

The American Council on Science and Health said that denialism of the facts of climate science and of climate change misrepresents verifiable data and information as political opinion.

Anti-intellectualism puts scientists in the public view and forces them

to align with either a liberal or a conservative political stance.

Moreover, 53% of Republican U.S. Representatives and 74% of Republican

Senators deny the scientific facts of the causes of climate change.

In the rural U.S., anti-intellectualism is an essential feature of the religious culture of Christian fundamentalism.

Some Protestant churches and the Roman Catholic Church have directly

published their collective support for political action to counter

climate change, whereas Southern Baptists and Evangelicals

have denounced belief in climate change as a sin, and have dismissed

scientists as intellectuals attempting to create "Neo-nature paganism". People of fundamentalist religious belief tend to report not seeing evidence of global warming.

Corporate mass media

The

reportage of corporate mass-communications media appealed to societal

anti-intellectualism by misrepresenting university life in the U.S.,

where the students' pursuit of book learning (intellectualism) was

secondary to the after-school social life. That the reactionary

ideology communicated in mass-media reportage misrepresented the

liberal political activism and social protest of students as frivolous,

social activities thematically unrelated to the academic curriculum,

which is the purpose of attending university. In Anti-intellectualism in American Media (2004), Dane Clausen identified the contemporary anti-intellectualist bent of manufactured consent that is inherent to commodified information:

The effects of mass media on attitudes toward intellect are certainly multiple and ambiguous. On the one hand, mass communications greatly expand the sheer volume of information available for public consumption. On the other hand, much of this information comes pre-interpreted for easy digestion and laden with hidden assumption, saving consumers the work of having to interpret it for themselves. Commodified information naturally tends to reflect the assumptions and interests of those who produce it, and its producers are not driven entirely by a passion to promote critical reflection.

The editorial perspective of the corporate mass-media misrepresented

intellectualism as a profession that is separate and apart from the jobs

and occupations of regular folk. In presenting academically successful

students as social failures, an undesirable social status for the

average young man and young woman, corporate media established to the

U.S. mainstream their opinion that the intellectualism of book-learning

is a form of mental deviancy, thus, most people would shun intellectuals

as friends, lest they risk social ridicule and ostracism. Hence, the popular acceptance of anti-intellectualism lead to populist rejection of the intelligentsia for resolving the problems of society. Moreover, in the book Inventing the Egghead: The Battle over Brainpower in American Culture (2013), Aaron Lecklider indicated that the contemporary ideological dismissal of the intelligentsia

derived from the corporate media's reactionary misrepresentations of

intellectual men and women as lacking the common-sense of regular folk.

Confirmation bias

In the field of psychology, confirmation bias is the mental phenomenon that confirms the validity of a person's self-accepted beliefs, ideals, and values,

to create emotional hostility (anti-intellectualism) towards and

mistrust of other beliefs, ideals, and value systems to which the

anti-intellectual person has not been exposed; thus, confirmation bias

is a symptom of anti-intellectualism. The writer Isaac Asimov,

speaking of this, said that "There is a cult of ignorance in the United

States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism

has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and

cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that

'my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.' "

In Europe

Communism

In the first decade after the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks suspected the Tsarist intelligentsia as potentially traitorous of the proletariat, thus, the initial Soviet government comprised men and women without much formal education. Moreover, the deposed propertied classes were termed Lishentsy

("the disenfranchised"), whose children were excluded from education;

eventually, some 200 Tsarist intellectuals such as writers,

philosophers, scientists, and engineers were deported to Germany on Philosophers' ships in 1922; others were deported to Latvia and to Turkey in 1923.

During the revolutionary

period, the pragmatic Bolsheviks employed "bourgeois experts" to manage

the economy, industry, and agriculture, and so learn from them. After

the Russian Civil War (1917–22), to achieve socialism, the USSR (1922–91) emphasised literacy and education in service to modernising the country via an educated working class intelligentsia, rather than an Ivory Tower intelligentsia. During the 1930s and the 1950s, Joseph Stalin

replaced Lenin's intelligentsia with a "communist" intelligentsia,

loyal to him and with a specifically Soviet world view, thereby

producing the pseudoscientific theories of Lysenkoism and Japhetic theory.

Fascism

Active philosopher: Giovanni Gentile, intellectual father of Italian Fascism.

The idealist philosopher Giovanni Gentile established the intellectual basis of Fascist ideology with the autoctisi

(self-realisation) via concrete thinking that distinguished between the

good (active) intellectual and the bad (passive) intellectual:

Fascism combats ... not intelligence, but intellectualism... which is... a sickness of the intellect... not a consequence of its abuse, because the intellect cannot be used too much... it derives from the false belief that one can segregate oneself from life.

— Giovanni Gentile, addressing a Congress of Fascist Culture, Bologna, 30 March 1925

To counter the "passive intellectual" who used his or her intellect

abstractly, and therefore was "decadent", he proposed the "concrete

thinking" of the active intellectual who applied intellect as praxis—a "man of action", like Fascist Benito Mussolini, versus the decadent Communist intellectual Antonio Gramsci. The passive intellectual stagnates intellect by objectifying ideas, thus establishing them as objects. Hence the Fascist rejection of materialist logic, because it relies upon a priori principles improperly counter-changed with a posteriori ones that are irrelevant to the matter-in-hand in deciding whether or not to act.

In the praxis of Gentile's concrete thinking criteria, such consideration of the a priori toward the properly a posteriori constitutes impractical, decadent intellectualism. Moreover, this fascist philosophy occurred parallel to Actual Idealism, his philosophic system; he opposed intellectualism

for its being disconnected from the active intelligence that gets

things done, i.e. thought is killed when its constituent parts are

labelled, and thus rendered as discrete entities.

Related to this, is the confrontation between the Spanish franquist General, Millán Astray, and the writer Miguel de Unamuno during the Dia de la Raza celebration at the University of Salamanca, in 1936, during the Spanish Civil War. The General exclaimed: ¡Muera la inteligencia! ¡Viva la Muerte! ("Death to intelligence! Long live death!"); the Falangists applauded.

In Asia

China

Imperial China

Qin Shi Huang (246–210 BC), the first Emperor of unified China, consolidated political thought, and power, by suppressing freedom of speech at the suggestion of Chancellor Li Si, who justified such anti-intellectualism by accusing the intelligentsia

of falsely praising the emperor, and of dissenting through libel. From

213 to 206 BC, it was generally thought that the works of the Hundred Schools of Thought were incinerated, especially the Shi Jing (Classic of Poetry, c. 1000 BC) and the Shujing (Classic of History, c. 6th century BC). The exceptions were books by Qin historians, and books of Legalism, an early type of totalitarianism—and the Chancellor's philosophic school (see the Burning of books and burying of scholars).

However, upon further inspection of Chinese historical annals such as

the Shi Ji and the Han Shu, this was found not to be the case. The Qin

Empire privately kept one copy of each of these books in the Imperial

Library but it publicly ordered that the books should be banned. Those

who owned copies were ordered to surrender the books to be burned; those

who refused were executed. This eventually led to the loss of most

ancient works of literature and philosophy when Xiang Yu burned down the Qin palace in 208BC.

People's Republic of China

The Cultural Revolution was a politically violent decade (1966–76) of wide-ranging social engineering of the People's Republic of China by its leader Chairman Mao. After several national policy crises, Mao, to regain public prestige and control of the Communist Party of China

(CPC), on 16 May 1966, announced that the Party and Chinese society

were permeated with liberal bourgeois elements who meant to restore capitalism to China, and that said people could only be removed with post–revolutionary class struggle. To that effect, China's youth nationally organised into Red Guards,

hunting the liberal bourgeois elements subverting the CCP and Chinese

society. The Red Guards acted nationally, purging the country, the

military, urban workers, and the leaders of the CCP. The Red Guards were

particularly aggressive in attacking their teachers and professors,

causing most schools and universities to be shut down once the Cultural

Revolution began. Three years later, in 1969, Mao declared the Cultural

Revolution ended; yet the political intrigues continued until 1976,

concluding with the arrest of the Gang of Four, the de facto end of the Cultural Revolution.

Democratic Kampuchea

When the Communist Party of Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge (1951–81), established their regime as Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979) in Cambodia,

their anti-intellectualism which idealised the country and demonised

the cities was immediately imposed on the country in order to establish agrarian socialism, thus, they emptied cities in order to purge the Khmer nation of every traitor, enemy of the state, and intellectual, often symbolised by eyeglasses (see the Killing Fields).

Ottoman Empire

Some of the Armenian intellectuals who were detained, deported, and killed in the Armenian Genocide of 1915

In the early stages of the Armenian Genocide of 1915, around 2,300 Armenian intellectuals were deported from Constantinople (Istanbul) and subsequently mostly murdered by the Ottoman government. The event has been described by historians as a decapitation strike, which intended to deprive the Armenian population of an intellectual leadership and a chance of resistance.