The shrinking Aral Sea, an example of poor water resource management diverted for irrigation.

Environmental resource management is the management of the interaction and impact of human societies on the environment.

It is not, as the phrase might suggest, the management of the

environment itself. Environmental resources management aims to ensure

that ecosystem services are protected and maintained for future human generations, and also maintain ecosystem integrity through considering ethical, economic, and scientific (ecological) variables.

Environmental resource management tries to identify factors affected by

conflicts that rise between meeting needs and protecting resources. It is thus linked to environmental protection, sustainability and integrated landscape management.

Significance

Environmental

resource management is an issue of increasing concern, as reflected in

its prevalence in seminal texts influencing global sociopolitical frameworks such as the Brundtland Commission's Our Common Future, which highlighted the integrated nature of environment and international development and the Worldwatch Institute's annual State of the World reports.

The environment determines the nature of people, animals, plants, and places around the Earth, affecting behaviour, religion, culture and economic practices.

Scope

Improved agricultural practices such as these terraces in northwest Iowa can serve to preserve soil and improve water quality

Environmental resource management can be viewed from a variety of

perspectives. It involves the management of all components of the biophysical environment, both living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic), and the relationships among all living species and their habitats.

The environment also involves the relationships of the human

environment, such as the social, cultural and economic environment, with

the biophysical environment. The essential aspects of environmental

resource management are ethical, economical, social, and technological.

These underlie principles and help make decisions.

The concept of environmental determinism, probabilism and

possibilism are significant in the concept of environmental resource

management.

Environmental resource management covers many areas in science, including geography, biology, social sciences, political sciences, public policy, ecology, physics, chemistry, sociology, psychology, and physiology.

Aspects

Ethical

Environmental resource management strategies are intrinsically driven by conceptions of human-nature relationships.

Ethical aspects involve the cultural and social issues relating to the

environment, and dealing with changes to it. "All human activities take

place in the context of certain types of relationships between society

and the bio-physical world (the rest of nature),"

and so, there is a great significance in understanding the ethical

values of different groups around the world. Broadly speaking, two

schools of thought exist in environmental ethics: Anthropocentrism and Ecocentrism, each influencing a broad spectrum of environmental resource management styles along a continuum.

These styles perceive "...different evidence, imperatives, and

problems, and prescribe different solutions, strategies, technologies,

roles for economic sectors, culture, governments, and ethics, etc."

Anthropocentrism

Anthropocentrism, "...an inclination to evaluate reality exclusively in terms of human values,"

is an ethic reflected in the major interpretations of Western religions

and the dominant economic paradigms of the industrialized world.

Anthropocentrism looks at nature as existing solely for the benefit of

humans, and as a commodity to use for the good of humanity and to

improve human quality of life.

Anthropocentric environmental resource management is therefore not the

conservation of the environment solely for the environment's sake, but

rather the conservation of the environment, and ecosystem structure, for

humans' sake.

Ecocentrism

Ecocentrists believe in the intrinsic value of nature while

maintaining that human beings must use and even exploit nature to

survive and live. It is this fine ethical line that ecocentrists navigate between fair use and abuse. At an extreme of the ethical scale, ecocentrism includes philosophies such as ecofeminism and deep ecology, which evolved as a reaction to dominant anthropocentric paradigms.

"In its current form, it is an attempt to synthesize many old and some

new philosophical attitudes about the relationship between nature and

human activity, with particular emphasis on ethical, social, and

spiritual aspects that have been downplayed in the dominant economic

worldview."

Economics

A water harvesting system collects rainwater from the Rock of Gibraltar into pipes that lead to tanks excavated inside the rock.

The economy functions within, and is dependent upon goods and services provided by natural ecosystems. The role of the environment is recognized in both classical economics and neoclassical economics

theories, yet the environment was a lower priority in economic policies

from 1950 to 1980 due to emphasis from policy makers on economic

growth.

With the prevalence of environmental problems, many economists embraced

the notion that, "If environmental sustainability must coexist for

economic sustainability, then the overall system must [permit]

identification of an equilibrium between the environment and the

economy." As such, economic policy makers began to incorporate the functions of the natural environment—or natural capital — particularly as a sink for wastes and for the provision of raw materials and amenities.

Debate continues among economists as to how to account for

natural capital, specifically whether resources can be replaced through

knowledge and technology, or whether the environment is a closed system

that cannot be replenished and is finite.

Economic models influence environmental resource management, in that

management policies reflect beliefs about natural capital scarcity. For

someone who believes natural capital is infinite and easily substituted,

environmental management is irrelevant to the economy.

For example, economic paradigms based on neoclassical models of closed

economic systems are primarily concerned with resource scarcity, and

thus prescribe legalizing the environment as an economic externality for

an environmental resource management strategy. This approach has often been termed 'Command-and-control'. Colby has identified trends in the development of economic paradigms, among them, a shift towards more ecological economics since the 1990s.

Ecology

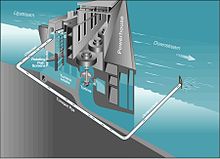

A diagram showing the juvenile fish bypass system, which allows young salmon and steelhead to safely pass the Rocky Reach Hydro Project in Washington

Fencing separates big game from vehicles along the Quebec Autoroute 73 in Canada.

"The pairing of significant uncertainty about the behaviour and

response of ecological systems with urgent calls for near-term action

constitutes a difficult reality, and a common lament" for many environmental resource managers. Scientific analysis of the environment deals with several dimensions of ecological uncertainty. These include: structural uncertainty resulting from the misidentification, or lack of information pertaining to the relationships between ecological variables; parameter uncertainty

referring to "uncertainty associated with parameter values that are not

known precisely but can be assessed and reported in terms of the

likelihood…of experiencing a defined range of outcomes"; and stochastic uncertainty stemming from chance or unrelated factors. Adaptive management is considered a useful framework for dealing with situations of high levels of uncertainty though it is not without its detractors.

A common scientific concept and impetus behind environmental resource management is carrying capacity.

Simply put, carrying capacity refers to the maximum number of organisms

a particular resource can sustain. The concept of carrying capacity,

whilst understood by many cultures over history, has its roots in Malthusian theory. An example is visible in the EU Water Framework Directive.

However, "it is argued that Western scientific knowledge ... is often

insufficient to deal with the full complexity of the interplay of

variables in environmental resource management.

These concerns have been recently addressed by a shift in environmental

resource management approaches to incorporate different knowledge

systems including traditional knowledge, reflected in approaches such as adaptive co-management community-based natural resource management and transitions management. among others.

Sustainability

Sustainability in environmental resource management involves managing

economic, social, and ecological systems both within and outside an

organizational entity so it can sustain itself and the system it exists

in.

In context, sustainability implies that rather than competing for

endless growth on a finite planet, development improves quality of life

without necessarily consuming more resources.

Sustainably managing environmental resources requires organizational

change that instills sustainability values that portrays these values

outwardly from all levels and reinforces them to surrounding

stakeholders. The end result should be a symbiotic relationship between the sustaining organization, community, and environment.

Many drivers compel environmental resource management to take

sustainability issues into account. Today's economic paradigms do not

protect the natural environment, yet they deepen human dependency on

biodiversity and ecosystem services. Ecologically, massive environmental degradation and climate change threaten the stability of ecological systems that humanity depends on. Socially, an increasing gap between rich and poor and the global North-South divide denies many access to basic human needs, rights, and education, leading to further environmental destruction. The planet's unstable condition is caused by many anthropogenic sources.

As an exceptionally powerful contributing factor to social and

environmental change, the modern organization has the potential to apply

environmental resource management with sustainability principals to

achieve highly effective outcomes. To achieve sustainable development

with environmental resource management an organisation should work

within sustainability principles, including social and environmental accountability,

long-term planning; a strong, shared vision; a holistic focus; devolved

and consensus decision making; broad stakeholder engagement and

justice; transparency measures; trust; and flexibility.

Current paradigm shifts

To

adjust to today's environment of quick social and ecological changes,

some organizations have begun to experiment with new tools and concepts.

Those that are more traditional and stick to hierarchical decision

making have difficulty dealing with the demand for lateral decision

making that supports effective participation. Whether it be a matter of ethics or just strategic advantage organizations are internalizing sustainability principles.

Some of the world's largest and most profitable corporations are

shifting to sustainable environmental resource management: Ford, Toyota,

BMW, Honda, Shell, Du Port, Sta toil, Swiss Re, Hewlett-Packard, and Unilever, among others. An extensive study by the Boston Consulting Group

reaching 1,560 business leaders from diverse regions, job positions,

expertise in sustainability, industries, and sizes of organizations,

revealed the many benefits of sustainable practice as well as its

viability.

It is important to note that though sustainability of environmental resource management has improved, corporate sustainability, for one, has yet to reach the majority of global companies operating in the markets.

The three major barriers to preventing organizations to shift towards

sustainable practice with environmental resource management are not

understanding what sustainability is; having difficulty modeling an

economically viable case for the switch; and having a flawed execution

plan, or a lack thereof.

Therefore, the most important part of shifting an organization to adopt

sustainability in environmental resource management would be to create a

shared vision and understanding of what sustainability is for that

particular organization, and to clarify the business case.

Stakeholders

Public sector

A conservation project in North Carolina involving the search for bog turtles was conducted by United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission and its volunteers

The public sector comprises the general government sector plus all public corporations including the central bank. In environmental resource management the public sector is responsible for administering natural resource management and implementing environmental protection legislation.

The traditional role of the public sector in environmental resource

management is to provide professional judgement through skilled

technicians on behalf of the public.

With the increase of intractable environmental problems, the public

sector has been led to examine alternative paradigms for managing

environmental resources.

This has resulted in the public sector working collaboratively with

other sectors (including other governments, private and civil) to

encourage sustainable natural resource management behaviors.

Private sector

The private sector comprises private corporations and non-profit institutions serving households. The private sector's traditional role in environmental resource management is that of the recovery of natural resources. Such private sector recovery groups include mining (minerals and petroleum), forestry and fishery organizations.

Environmental resource management undertaken by the private sectors

varies dependent upon the resource type, that being renewable or

non-renewable and private and common resources. Environmental managers from the private sector also need skills to manage collaboration within a dynamic social and political environment.

Civil society

Civil society

comprises associations in which societies voluntarily organise

themselves into and which represent a wide range of interests and ties. These can include community-based organisations, indigenous peoples' organizations and non-government organizations (NGO).

Functioning through strong public pressure, civil society can exercise

their legal rights against the implementation of resource management

plans, particularly land management plans. The aim of civil society in environmental resource management is to be included in the decision-making process by means of public participation. Public participation can be an effective strategy to invoke a sense of social responsibility of natural resources.

Tools

As with all

management functions, effective management tools, standards and systems

are required. An environmental management standard or system or protocol attempts to reduce environmental impact as measured by some objective criteria. The ISO 14001 standard is the most widely used standard for environmental risk management and is closely aligned to the European Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS). As a common auditing standard, the ISO 19011 standard explains how to combine this with quality management.

Other environmental management systems (EMS) tend to be based on the ISO 14001 standard and many extend it in various ways:

- The Green Dragon Environmental Management Standard is a five-level EMS designed for smaller organisations for whom ISO 14001 may be too onerous and for larger organisations who wish to implement ISO 14001 in a more manageable step-by-step approach,

- BS 8555 is a phased standard that can help smaller companies move to ISO 14001 in six manageable steps,

- The Natural Step focuses on basic sustainability criteria and helps focus engineering on reducing use of materials or energy use that is unsustainable in the long term,

- Natural Capitalism advises using accounting reform and a general biomimicry and industrial ecology approach to do the same thing,

- US Environmental Protection Agency has many further terms and standards that it defines as appropriate to large-scale EMS,

- The UN and World Bank has encouraged adopting a "natural capital" measurement and management framework,

- The European Union Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS).

Other strategies exist that rely on making simple distinctions rather than building top-down management "systems" using performance audits and full cost accounting. For instance, Ecological Intelligent Design divides products into consumables, service products or durables and unsaleables

— toxic products that no one should buy, or in many cases, do not

realize they are buying. By eliminating the unsaleables from the comprehensive outcome of any purchase, better environmental resource management is achieved without systems.

Recent successful cases have put forward the notion of integrated management.

It shares a wider approach and stresses out the importance of

interdisciplinary assessment. It is an interesting notion that might not

be adaptable to all cases.