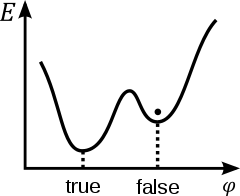

A scalar field φ in a false vacuum. Note that the energy E is higher than that in the true vacuum or ground state,

but there is a barrier preventing the field from classically rolling

down to the true vacuum. Therefore, the transition to the true vacuum

must be stimulated by the creation of high-energy particles or through quantum-mechanical tunneling.

In quantum field theory, a false vacuum is a hypothetical vacuum

that is somewhat, but not entirely, stable. It may last for a very long

time in that state, and might eventually move to a more stable state.

The most common suggestion of how such a change might happen is called bubble nucleation - if a small region of the universe by chance reached a more stable vacuum, this 'bubble' would spread.

A false vacuum may only exist at a local minimum of energy

and is therefore not stable, in contrast to a true vacuum, which exists

at a global minimum and is stable. A false vacuum may be very

long-lived, or metastable.

True vs false vacuum

A vacuum

or vacuum state is defined as a space with as little energy in it as

possible. Despite the name the vacuum state still has quantum fields. A

true vacuum is a global minimum of energy, and coincides with a local

vacuum. This configuration is stable.

It is possible that the process of removing the largest amount of

energy and particles possible from a normal space results in a

different configuration of quantum fields with a local minimum

of energy. This local minimum is called a "false vacuum". In this

case, there would be a barrier to entering the true vacuum. Perhaps the

barrier is so high that it has never yet been overcome anywhere in the

universe.

A false vacuum is unstable due to the quantum tunnelling of instantons to lower energy states. Tunnelling can be caused by quantum fluctuations or the creation of high-energy particles. The false vacuum is a local minimum, but not the lowest energy state.

Standard Model vacuum

If the Standard Model is correct, the particles and forces we observe in our universe exist as they do because of underlying quantum fields. Quantum fields can have states of differing stability, including 'stable', 'unstable', or 'metastable'

(meaning very long-lived but not completely stable). If a more stable

vacuum state were able to arise, then existing particles and forces

would no longer arise as they do in the universe's present state.

Different particles or forces would arise from (and be shaped by)

whatever new quantum states arose. The world we know depends upon these

particles and forces, so if this happened, everything around us, from subatomic particles to galaxies, and all fundamental forces,

would be reconstituted into new fundamental particles and forces and

structures. The universe would lose all of its present structures and

become inhabited by new ones (depending upon the exact states involved)

based upon the same quantum fields.

Stability and instability of the vacuum

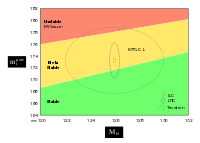

Diagram showing the Higgs boson and top quark masses, which could indicate whether our universe is stable, or a long-lived 'bubble'.

The outer dotted line is the current measurement uncertainties; the

inner ones show predicted sizes after completion of future physics

programs, but their location could be anywhere inside the outer.

Many scientific models of the universe have included the possibility that it exists as a long-lived, but not completely stable, sector of space, which could potentially at some time be destroyed upon 'toppling' into a more stable vacuum state.

A universe in a false vacuum state allows for the formation of a

bubble of more stable "true vacuum" at any time or place. This bubble

expands outward at the speed of light.

The Standard Model of particle physics opens the possibility of calculating, from the masses of the Higgs boson and the top quark, whether the universe's present electroweak vacuum state is likely to be stable or merely long-lived. (This was sometimes misreported as the Higgs boson "ending" the universe).

A 125–127 GeV Higgs mass seems to be extremely close to the boundary for stability (estimated in 2012 as 123.8–135.0 GeV). However, a definitive answer requires much more precise measurements of the top quark's pole mass, and new physics beyond the Standard Model of Particle Physics could drastically change this picture.

Implications

Existential threat

In a 2005 paper published in Nature, as part of their investigation into global catastrophic risks, MIT physicist Max Tegmark and Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom calculate the natural risks of the destruction of the Earth at less than 1 per gigayear from all events, including a transition to a lower vacuum state. They argue that due to observer selection effects,

we might underestimate the chances of being destroyed by vacuum decay

because any information about this event would reach us only at the

instant when we too were destroyed. This is in contrast to events like

risks from impacts, gamma-ray bursts, supernovae and hypernovae, whose frequencies we have adequate direct measures of.

If measurements of these particles suggests that our universe

lies within a false vacuum of this kind, then it would imply—more than

likely in many billions of years—that it could cease to exist as we know it, if a true vacuum happened to nucleate.

In a study posted on the arXiv in March 2015,

it was pointed out that the vacuum decay rate could be vastly increased

in the vicinity of black holes, which would serve as a nucleation seed. According to this study a potentially catastrophic vacuum decay could be triggered any time by primordial black holes, should they exist. If particle collisions produce mini black holes then energetic collisions such as the ones produced in the Large Hadron Collider

(LHC) could trigger such a vacuum decay event. However the authors say

that this is not a reason to expect the universe to collapse, because if

such mini black holes can be created in collisions, they would also be

created in the much more energetic collisions of cosmic radiation

particles with planetary surfaces. And if there are primordial mini

black holes they should have triggered the vacuum decay long ago.

Rather, they see their calculations as evidence that there must be

something else preventing vacuum decay.

Inflation

It would also have implications for other aspects of physics, and would suggest that the Higgs self-coupling λ and its βλ

function could be very close to zero at the Planck scale, with

"intriguing" implications, including for theories of gravity and

Higgs-based inflation.

A future electron-positron collider would be able to provide the

precise measurements of the top quark needed for such calculations.

Vacuum decay

Vacuum decay would be theoretically possible if our universe had a

false vacuum in the first place, an issue that was highly theoretical

and far from resolved in 1982. If this were the case, a bubble of lower-energy vacuum could come to exist by chance or otherwise in our universe, and catalyze

the conversion of our universe to a lower energy state in a volume

expanding at nearly the speed of light, destroying all of the observable universe without forewarning. Chaotic Inflation Theory suggests that the universe may be in either a false vacuum or a true vacuum state.

A paper by Coleman and de Luccia which attempted to include

simple gravitational assumptions into these theories noted that if this

was an accurate representation of nature, then the resulting universe

"inside the bubble" in such a case would appear to be extremely unstable

and would almost immediately collapse.

In general,

gravitation makes the probability of vacuum decay smaller; in the

extreme case of very small energy-density difference, it can even

stabilize the false vacuum, preventing vacuum decay altogether. We

believe we understand this. For the vacuum to decay, it must be possible

to build a bubble of total energy zero. In the absence of gravitation,

this is no problem, no matter how small the energy-density difference;

all one has to do is make the bubble big enough, and the volume/surface

ratio will do the job. In the presence of gravitation, though, the

negative energy density of the true vacuum distorts geometry within the

bubble with the result that, for a small enough energy density, there is

no bubble with a big enough volume/surface ratio. Within the bubble,

the effects of gravitation are more dramatic. The geometry of space-time

within the bubble is that of anti-de Sitter space, a space much like conventional de Sitter space

except that its group of symmetries is O(3, 2) rather than O(4, 1).

Although this space-time is free of singularities, it is unstable under

small perturbations, and inevitably suffers gravitational collapse of

the same sort as the end state of a contracting Friedmann universe. The time required for the collapse of the interior universe is on the order of ... microseconds or less.

The possibility that we are living in a false vacuum has never been a

cheering one to contemplate. Vacuum decay is the ultimate ecological

catastrophe; in the new vacuum there are new constants of nature; after

vacuum decay, not only is life as we know it impossible, so is chemistry

as we know it. However, one could always draw stoic

comfort from the possibility that perhaps in the course of time the new

vacuum would sustain, if not life as we know it, at least some

structures capable of knowing joy. This possibility has now been

eliminated.

The second special case is decay into a space of vanishing cosmological constant, the case that applies if we are now living in the debris of a false vacuum which decayed at some early cosmic epoch. This case presents us with less interesting physics and with fewer occasions for rhetorical excess than the preceding one. It is now the interior of the bubble that is ordinary Minkowski space...

Sidney Coleman and Frank De Luccia.The second special case is decay into a space of vanishing cosmological constant, the case that applies if we are now living in the debris of a false vacuum which decayed at some early cosmic epoch. This case presents us with less interesting physics and with fewer occasions for rhetorical excess than the preceding one. It is now the interior of the bubble that is ordinary Minkowski space...

Such an event would be one possible doomsday event. It was used as a plot device in a science-fiction story in 1988 by Geoffrey A. Landis, in 2000 by Stephen Baxter, in 2002 by Greg Egan in his novel Schild's Ladder, and in 2015 by Alastair Reynolds in his novel Poseidon's Wake.

In theory, either high enough energy concentrations or random

chance could trigger the tunneling needed to set this event in motion.

However an immense number of ultra-high energy particles

and events have occurred in the history of our universe, dwarfing by

many orders of magnitude any events at human disposal. Hut and Rees note that, because we have observed cosmic ray collisions

at much higher energies than those produced in terrestrial particle

accelerators, these experiments should not, at least for the foreseeable

future, pose a threat to our current vacuum. Particle accelerators have

reached energies of only approximately eight tera electron volts (8×1012 eV). Cosmic ray collisions have been observed at and beyond energies of 1018 eV, a million times more powerful – the so-called Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin limit – and other cosmic events may be more powerful yet. Against this, John Leslie has argued

that if present trends continue, particle accelerators will exceed the

energy given off in naturally occurring cosmic ray collisions by the

year 2150. Fears of this kind were raised by critics of both the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and the Large Hadron Collider at the time of their respective proposal, and determined to be unfounded by scientific inquiry.

Bubble nucleation

In

the theoretical physics of the false vacuum, the system moves to a

lower energy state – either the true vacuum, or another, lower energy

vacuum – through a process known as bubble nucleation.

In this, instanton effects cause a bubble to appear in which fields

have their true vacuum values inside. Therefore, the interior of the

bubble has a lower energy. The walls of the bubble (or domain walls) have a surface tension,

as energy is expended as the fields roll over the potential barrier to

the lower energy vacuum. The most likely size of the bubble is

determined in the semi-classical approximation to be such that the

bubble has zero total change in the energy: the decrease in energy by

the true vacuum in the interior is compensated by the tension of the

walls.

Joseph Lykken has said that study of the exact properties of the Higgs boson could shed light on the possibility of vacuum collapse.

Expansion of bubble

Any

increase in size of the bubble will decrease its potential energy, as

the energy of the wall increases as the surface area of a sphere but the negative contribution of the interior increases more quickly, as the volume of a sphere .

Therefore, after the bubble is nucleated, it quickly begins expanding

at very nearly the speed of light. The excess energy contributes to the

very large kinetic energy of the walls. If two bubbles are nucleated and

they eventually collide, it is thought that particle production would

occur where the walls collide.

The tunneling rate is increased by increasing the energy

difference between the two vacua and decreased by increasing the height

or width of the barrier.

Gravitational effects

The addition of gravity

to the story leads to a considerably richer variety of phenomena. The

key insight is that a false vacuum with positive potential energy

density is a de Sitter vacuum, in which the potential energy acts as a cosmological constant and the Universe is undergoing the exponential expansion of de Sitter space. This leads to a number of interesting effects, first studied by Coleman and de Luccia.

Development of theories

Alan Guth, in his original proposal for cosmic inflation, proposed that inflation could end through quantum mechanical bubble nucleation of the sort described above. See History of Chaotic inflation theory.

It was soon understood that a homogeneous and isotropic universe could

not be preserved through the violent tunneling process. This led Andrei Linde and, independently, Andreas Albrecht and Paul Steinhardt,

to propose "new inflation" or "slow roll inflation" in which no

tunneling occurs, and the inflationary scalar field instead rolls down a

gentle slope.