French President Charles de Gaulle shaking hands with West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer in Bonn, 1958, ending the French–German enmity

Democratic peace theory is a theory which posits that democracies are hesitant to engage in armed conflict with other identified democracies.

In contrast to theories explaining war engagement, it is a "theory of

peace" outlining motives that dissuade state-sponsored violence.

Some theorists prefer terms such as "mutual democratic pacifism" (Rosato 2003) or "inter-democracy nonaggression hypothesis" so as to clarify that a state of peace is not singular to democracies, but rather that it is easily sustained between democratic nations (Archibugi 2008).

Among proponents of the democratic peace theory, several factors are held as motivating peace between democratic states:

- Democratic leaders are forced to accept culpability for war losses to a voting public;

- Publicly accountable statespeople are inclined to establish diplomatic institutions for resolving international tensions;

- Democracies are not inclined to view countries with adjacent policy and governing doctrine as hostile;

- Democracies tend to possess greater public wealth than other states, and therefore eschew war to preserve infrastructure and resources.

Those who dispute this theory often do so on grounds that it conflates correlation with causation, and that the academic definitions of 'democracy' and 'war' can be manipulated so as to manufacture an artificial trend (Pugh 2005).

History

Immanuel Kant

Though the democratic peace theory was not rigorously or

scientifically studied until the 1960s, the basic principles of the

concept had been argued as early as the 1700s in the works of

philosopher Immanuel Kant and political theorist Thomas Paine. Kant foreshadowed the theory in his essay Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch

written in 1795, although he thought that a world with only

constitutional republics was only one of several necessary conditions

for a perpetual peace. Kant's theory was that a majority of the people

would never vote to go to war, unless in self-defense. Therefore, if all

nations were republics, it would end war, because there would be no

aggressors. In earlier but less cited works, Thomas Paine made similar

or stronger claims about the peaceful nature of republics. Paine wrote

in "Common Sense" in 1776: "The Republics of Europe are all (and we may

say always) in peace." Paine argued that kings would go to war out of

pride in situations where republics would not (Levy & Thompson 2011)(Paine 1945, p. 27). French historian and social scientist Alexis de Tocqueville also argued, in Democracy in America (1835–1840), that democratic nations were less likely to wage war.

Dean Babst,

a criminologist, was the first to do statistical research on this

topic. His academic paper supporting the theory was published in 1964 in

Wisconsin Sociologist; he published a slightly more popularized version, in 1972, in the trade journal Industrial Research. Both versions initially received little attention.

Melvin Small and J. David Singer

(1976, pp. 50–69) responded; they found an absence of wars between

democratic states with two "marginal exceptions", but denied that this

pattern had statistical significance. This paper was published in the Jerusalem Journal of International Relations

which finally brought more widespread attention to the theory, and

started the academic debate. A 1983 paper by political scientist Michael W. Doyle contributed further to popularizing the theory. Rudolph J. Rummel was another early researcher and drew considerable lay attention to the subject in his later works.

Maoz & Abdolali (1989) extended the research to lesser

conflicts than wars. Bremer (1992) and Maoz & Russett (1993) found

the correlation between democracy and peacefulness remained significant

after controlling for many possible confounding variables. This moved

the theory into the mainstream of social science. Supporters of realism in international relations

and others responded by raising many new objections. Other researchers

attempted more systematic explanations of how democracy might cause

peace (Köchler 1995), and of how democracy might also affect other aspects of foreign relations such as alliances and collaboration (Ray 2003).

There have been numerous further studies in the field since these pioneering works.

Most studies have found some form of democratic peace exists, although

neither methodological disputes nor doubtful cases are entirely resolved

(Kinsella 2005).

Definitions

Research on the democratic peace theory has to define "democracy" and "peace" (or, more often, "war").

Defining democracy

Democracies

have been defined differently by different theorists and researchers;

this accounts for some of the variations in their findings. Some

examples:

Small and Singer (1976) define democracy as a nation that (1)

holds periodic elections in which the opposition parties are as free to

run as government parties, (2) allows at least 10% of the adult

population to vote, and (3) has a parliament that either controls or

enjoys parity with the executive branch of the government.

Doyle (1983)

requires (1) that "liberal regimes" have market or private property

economics, (2) they have policies that are internally sovereign, (3)

they have citizens with juridical rights, and (4) they have

representative governments. Either 30% of the adult males were able to

vote or it was possible for every man to acquire voting rights as by

attaining enough property. He allows greater power to hereditary

monarchs than other researchers; for example, he counts the rule of Louis-Philippe of France as a liberal regime.

Ray (1995) requires that at least 50% of the adult population is

allowed to vote and that there has been at least one peaceful,

constitutional transfer of executive power from one independent

political party to another by means of an election. This definition

excludes long periods often viewed as democratic. For example, the

United States until 1800, India from independence until 1979, and Japan

until 1993 were all under one-party rule, and thus would not be counted

under this definition (Ray 1995, p. 100).

Rummel (1997) states that "By democracy is meant liberal

democracy, where those who hold power are elected in competitive

elections with a secret ballot and wide franchise (loosely understood as

including at least 2/3 of adult males); where there is freedom of

speech, religion, and organization; and a constitutional framework of

law to which the government is subordinate and that guarantees equal

rights."

Non-binary classifications

The

above definitions are binary, classifying nations into either

democracies or non-democracies. Many researchers have instead used more

finely grained scales. One example is the Polity data series

which scores each state on two scales, one for democracy and one for

autocracy, for each year since 1800; as well as several others.

The use of the Polity Data has varied. Some researchers have done

correlations between the democracy scale and belligerence; others have

treated it as a binary classification by (as its maker does) calling all

states with a high democracy score and a low autocracy score

democracies; yet others have used the difference of the two scores,

sometimes again making this into a binary classification (Gleditsch 1992).

Young democracies

Several

researchers have observed that many of the possible exceptions to the

democratic peace have occurred when at least one of the involved

democracies was very young. Many of them have therefore added a

qualifier, typically stating that the peacefulness apply to democracies

older than three years (Doyle 1983,

Russett 1993, Rummel 1997, Weart 1998). Rummel (1997) argues that this

is enough time for "democratic procedures to be accepted, and democratic

culture to settle in." Additionally, this may allow for other states to

actually come to the recognition of the state as a democracy.

Mansfield and Snyder

(2002, 2005), while agreeing that there have been no wars between

mature liberal democracies, state that countries in transition to

democracy are especially likely to be involved in wars. They find that

democratizing countries are even more warlike than stable democracies,

stable autocracies or even countries in transition towards autocracy.

So, they suggest caution in eliminating these wars from the analysis,

because this might hide a negative aspect of the process of

democratization. A reanalysis of the earlier study's statistical results (Braumoeller 2004)

emphasizes that the above relationship between democratization and war

can only be said to hold for those democratizing countries where the

executive lacks sufficient power, independence, and institutional

strength. A review (Ray 2003)

cites several other studies finding that the increase in the risk of

war in democratizing countries happens only if many or most of the

surrounding nations are undemocratic. If wars between young democracies

are included in the analysis, several studies and reviews still find

enough evidence supporting the stronger claim that all democracies,

whether young or established, go into war with one another less

frequently (Ray 1998), (Ray 2003), (Hegre 2004), while some do not (Schwartz & Skinner 2002, p. 159).

Defining war

Quantitative

research on international wars usually define war as a military

conflict with more than 1000 killed in battle in one year. This is the

definition used in the Correlates of War Project

which has also supplied the data for many studies on war. It turns out

that most of the military conflicts in question fall clearly above or

below this threshold (Ray 1995, p. 103).

Some researchers have used different definitions. For example,

Weart (1998) defines war as more than 200 battle deaths. Russett (1993,

p. 50), when looking at Ancient Greece, only requires some real battle

engagement, involving on both sides forces under state authorization.

Militarized Interstate Disputes

(MIDs), in the Correlates of War Project classification, are lesser

conflicts than wars. Such a conflict may be no more than military

display of force with no battle deaths. MIDs and wars together are

"militarized interstate conflicts" or MICs. MIDs include the conflicts

that precede a war; so the difference between MIDs and MICs may be less

than it appears.

Statistical analysis and concerns about degrees of freedom

are the primary reasons for using MID's instead of actual wars. Wars

are relatively rare. An average ratio of 30 MIDs to one war provides a

richer statistical environment for analysis (Mousseau & Shi 1999).

Monadic vs. dyadic peace

Most research is regarding the dyadic peace, that democracies do not fight one another. Very few researchers have supported the monadic

peace, that democracies are more peaceful in general. There are some

recent papers that find a slight monadic effect. Müller and Wolff

(2004), in listing them, agree "that democracies on average might be

slightly, but not strongly, less warlike than other states," but general

"monadic explanations is neither necessary nor convincing." They note

that democracies have varied greatly in their belligerence against

non-democracies.

Possible exceptions

Some scholars support the democratic peace on probabilistic grounds:

since many wars have been fought since democracies first arose, we might

expect a proportionate number of wars to have occurred between

democracies, if democracies fought each other as freely as other pairs

of states; but proponents of democratic peace theory claim that the

number is much less than might be expected. However, opponents of the theory argue this is mistaken and claim there are numerous examples of wars between democracies (Schwartz & Skinner 2002, p. 159).

Historically, cases commonly cited as exceptions include the Sicilian Expedition, the Spanish–American War, and more recently the Kargil War (White 2005). Doyle (1983) cites the Paquisha War and the Lebanese air force's intervention in the Six-Day War.

The total number of cases suggested in the literature is at least 50.

The data set Bremer (1993) was using showed one exception, the French-Thai War of 1940; Gleditsch (1995) sees the (somewhat technical) state of war between Finland and UK during World War II,

as a special case, which should probably be treated separately: an

incidental state of war between democracies during large multi-polar

wars (Gowa 1999; Maoz 1997, p. 165). However, the UK did bomb Finland,

implying the war was not only on paper. Page Fortna (2004) discusses the

1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the Kargil War

as exceptions, finding the latter to be the most significant. However,

the status of these countries as being truly democratic is a matter of

debate. For instance, in Spain in 1898, two parties alternated in the

government in a controlled process known as el turno pacífico,

and the caciques, powerful local figures, were used to manipulate

election results, and as a result resentment of the system slowly built

up over time and important nationalist movements as well as unions

started to form. Similarly, the Turkish intervention in Cyprus occurred

only after the Cypriot elected government was abolished in a coup

sponsored by the military government of Greece.

Limiting the theory to only truly stable and genuine democracies

leads to a very restrictive set of highly prosperous nations with little

incentive in armed conflict that might harm their economies, in which

the theory might be expected to hold virtually by definition.

One advocate of the democratic peace explains that his reason to

choose a definition of democracy sufficiently restrictive to exclude all wars between democracies are what "might be disparagingly termed public relations":

students and politicians will be more impressed by such a claim than by

claims that wars between democracies are less likely (Ray 1998, p. 89).

Statistical difficulties due to newness of democracy

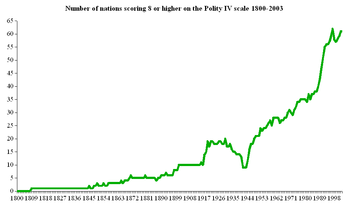

Number of nations 1800–2003 scoring 8 or higher on Polity IV scale.

There have been no wars and in Wayman's (2002) listing of interliberal

MIDs no conflict causing any battle deaths between these nations.

One problem with the research on wars is that, as the Realist

Mearsheimer (1990, p. 50) put it, "democracies have been few in number

over the past two centuries, and thus there have been few opportunities

where democracies were in a position to fight one another". Democracies

have been very rare until recently. Even looser definitions of

democracy, such as Doyle's, find only a dozen democracies before the

late nineteenth century, and many of them short-lived or with limited

franchise (Doyle 1983), (Doyle 1997, p. 261). Freedom House finds no independent state with universal suffrage in 1900.

Wayman (1998), a supporter of the theory, states that "If we rely

solely on whether there has been an inter-democratic war, it is going

to take many more decades of peace to build our confidence in the

stability of the democratic peace".

Studying lesser conflicts

Many

researchers have reacted to this limitation by studying lesser

conflicts instead, since they have been far more common. There have been

many more MIDs than wars; the Correlates of War Project counts several

thousand during the last two centuries. A review (Ray 2003)

lists many studies that have reported that democratic pairs of states

are less likely to be involved in MIDs than other pairs of states.

Another study (Hensel, Goertz & Diehl 2000)

finds that after both states have become democratic, there is a

decreasing probability for MIDs within a year and this decreases almost

to zero within five years.

When examining the inter-liberal MIDs in more detail, one study (Wayman 2002)

finds that they are less likely to involve third parties, and that the

target of the hostility is less likely to reciprocate, if the target

reciprocates the response is usually proportional to the provocation,

and the disputes are less likely to cause any loss of life. The most

common action was "Seizure of Material or Personnel".

Studies find that the probability that disputes between states

will be resolved peacefully is positively affected by the degree of

democracy exhibited by the lesser democratic state involved in that

dispute. Disputes between democratic states are significantly shorter

than disputes involving at least one undemocratic state. Democratic

states are more likely to be amenable to third party mediation when they

are involved in disputes with each other (Ray 2003).

In international crises that include the threat or use of

military force, one study finds that if the parties are democracies,

then relative military strength has no effect on who wins. This is

different from when nondemocracies are involved. These results are the

same also if the conflicting parties are formal allies (Gelpi & Griesdorf 2001).

Similarly, a study of the behavior of states that joined ongoing

militarized disputes reports that power is important only to

autocracies: democracies do not seem to base their alignment on the

power of the sides in the dispute (Werner & Lemke 1997).

Conflict initiation

According

to a 2017 review study, "there is enough evidence to conclude that

democracy does cause peace at least between democracies, that the

observed correlation between democracy and peace is not spurious" (Reiter 2017).

Most studies have looked only at who is involved in the conflicts

and ignored the question of who initiated the conflict. In many

conflicts both sides argue that the other side was initiator. Several

researchers, as described in (Gleditsch, Christiansen & Hegre 2004),

have argued that studying conflict initiation is of limited value,

because existing data about conflict initiation may be especially

unreliable. Even so, several studies have examined this. Reiter and Stam

(2003) argue that autocracies initiate conflicts against democracies

more frequently than democracies do against autocracies. Quackenbush and

Rudy (2006), while confirming Reiter and Stam's results, find that

democracies initiate wars against nondemocracies more frequently than

nondemocracies do to each other. Several following studies (Peceny & Beer 2003), (Peceny & Butler 2004), (Lai & Slater 2006)

have studied how different types of autocracies with different

institutions vary regarding conflict initiation. Personalistic and

military dictatorships may be particularly prone to conflict initiation,

as compared to other types of autocracy such as one party states, but also more likely to be targeted in a war having other initiators.

One 2017 study found that democracies are no less likely to settle border disputes peacefully than non-democracies (Gibler & Owsiak 2017).

Internal violence and genocide

Most

of this article discusses research on relations between states.

However, there is also evidence that democracies have less internal

systematic violence. For instance, one study finds that the most

democratic and the most authoritarian states have few civil wars,

and intermediate regimes the most. The probability for a civil war is

also increased by political change, regardless whether toward greater

democracy or greater autocracy. Intermediate regimes continue to be the

most prone to civil war, regardless of the time since the political

change. In the long run, since intermediate regimes are less stable than

autocracies, which in turn are less stable than democracies, durable

democracy is the most probable end-point of the process of democratization (Hegre et al. 2001). Abadie (2004) study finds that the most democratic nations have the least terrorism. Harff (2003) finds that genocide and politicide are rare in democracies. Rummel (1997) finds that the more democratic a regime, the less its democide. He finds that democide has killed six times as many people as battles.

Davenport and Armstrong (2004) lists several other studies and

states: "Repeatedly, democratic political systems have been found to

decrease political bans, censorship, torture, disappearances and mass

killing, doing so in a linear fashion across diverse measurements,

methodologies, time periods, countries, and contexts." It concludes:

"Across measures and methodological techniques, it is found that below a

certain level, democracy has no impact on human rights violations, but

above this level democracy influences repression in a negative and

roughly linear manner." Davenport and Armstrong (2003) states that

thirty years worth of statistical research has revealed that only two

variables decrease human rights violations: political democracy and

economic development.

Abulof and Goldman add a caveat, focusing on the contemporary

Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Statistically, a MENA democracy

makes a country more prone to both the onset and incidence of civil war,

and the more democratic a MENA state is, the more likely it is to

experience violent intrastate strife. Moreover, anocracies

do not seem to be predisposed to civil war, either worldwide or in

MENA. Looking for causality beyond correlation, they suggest that

democracy's pacifying effect is partly mediated through societal

subscription to self-determination and popular sovereignty. This may

turn “democratizing nationalism” to a long-term prerequisite, not just

an immediate hindrance, to peace and democracy (Abulof & Goldman 2015).

Explanations

These

theories have traditionally been categorized into two groups:

explanations that focus on democratic norms and explanations that focus

on democratic

political structures (Gelpi & Griesdorf 2001), (Braumoeller 1997).

Note that they usually are meant to be explanations for little violence

between democracies, not for a low level of internal violence in

democracies.

Several of these mechanisms may also apply to countries of similar systems. The book Never at War finds evidence for an oligarchic peace. One example is the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in which the Sejm resisted and vetoed most royal proposals for war, like those of Władysław IV Vasa.

Democratic norms

One

example from the first group is that liberal democratic culture may

make the leaders accustomed to negotiation and compromise (Weart 1998), (Müller & Wolff 2004).

Another that a belief in human rights may make people in democracies

reluctant to go to war, especially against other democracies. The

decline in colonialism, also by democracies, may be related to a change

in perception of non-European peoples and their rights (Ravlo & Gleditsch 2000).

Bruce Russett (1993, p. 5–11, 35, 59–62, 73–4) also argues that

the democratic culture affects the way leaders resolve conflicts. In

addition, he holds that a social norm emerged toward the end of the

nineteenth century; that democracies should not fight each other, which

strengthened when the democratic culture and the degree of democracy

increased, for example by widening the franchise. Increasing democratic

stability allowed partners in foreign affairs to perceive a nation as

reliably democratic. The alliances between democracies during the two

World Wars and the Cold War also strengthened the norms. He sees less

effective traces of this norm in Greek antiquity.

Hans Köchler

(1995) relates the question of transnational democracy to empowering

the individual citizen by involving him, through procedures of direct democracy,

in a country's international affairs, and he calls for the

restructuring of the United Nations Organization according to democratic

norms. He refers in particular to the Swiss practice of participatory democracy.

Mousseau (2000, 2005) argues that it is market-oriented

development that creates the norms and values that explain both

democracy and the peace. In less developed countries individuals often

depend on social networks that impose conformity to in-group norms and

beliefs, and loyalty to group leaders. When jobs are plentiful on the

market, in contrast, as in market-oriented developed countries,

individuals depend on a strong state that enforces contracts equally.

Cognitive routines emerge of abiding by state law rather than group

leaders, and, as in contracts, tolerating differences among individuals.

Voters in marketplace democracies thus accept only impartial ‘liberal’

governments, and constrain leaders to pursue their interests in securing

equal access to global markets and in resisting those who distort such

access with force. Marketplace democracies thus share common foreign

policy interests in the supremacy—and predictability—of international

law over brute power politics, and equal and open global trade over

closed trade and imperial preferences. When disputes do originate

between marketplace democracies, they are less likely than others to

escalate to violence because both states, even the stronger one,

perceive greater long-term interests in the supremacy of law over power

politics.

(Braumoeller 1997)

argues that liberal norms of conflict resolution vary because

liberalism takes many forms. By examining survey results from the newly

independent states of the former Soviet Union, the author demonstrates

that liberalism in that region bears a stronger resemblance to

19th-century liberal nationalism than to the sort of universalist,

Wilsonian liberalism described by democratic peace theorists, and that,

as a result, liberals in the region are more, not less, aggressive than non-liberals.

Democratic political structures

The case for institutional constraints goes back to Kant (1795), who wrote:

[I]f the consent of the citizens is required in order to decide that war should be declared (and in this constitution it cannot but be the case), nothing is more natural than that they would be very cautious in commencing such a poor game, decreeing for themselves all the calamities of war. Among the latter would be: having to fight, having to pay the costs of war from their own resources, having painfully to repair the devastation war leaves behind, and, to fill up the measure of evils, load themselves with a heavy national debt that would embitter peace itself and that can never be liquidated on account of constant wars in the future.

Democracy thus gives influence to those most likely to be killed or

wounded in wars, and their relatives and friends (and to those who pay

the bulk of the war taxes) Russett (1993, p. 30). This monadic theory

must, however, explain why democracies do attack non-democratic states.

One explanation is that these democracies were threatened or otherwise

were provoked by the non-democratic states. Doyle (1997, p. 272) argued

that the absence of a monadic peace is only to be expected: the same

ideologies that cause liberal states to be at peace with each other

inspire idealistic wars with the illiberal, whether to defend oppressed

foreign minorities or avenge countrymen settled abroad. Doyle also notes

(p. 292) liberal states do conduct covert operations against each

other; the covert nature of the operation, however, prevents the

publicity otherwise characteristic of a free state from applying to the

question

Studies show that democratic states are more likely than

autocratic states to win the wars. One explanation is that democracies,

for internal political and economic reasons, have greater resources.

This might mean that democratic leaders are unlikely to select other

democratic states as targets because they perceive them to be

particularly formidable opponents. One study finds that interstate wars

have important impacts on the fate of political regimes, and that the

probability that a political leader will fall from power in the wake of a

lost war is particularly high in democratic states (Ray 1998).

As described in (Gelpi & Griesdorf 2001),

several studies have argued that liberal leaders face institutionalized

constraints that impede their capacity to mobilize the state's

resources for war without the consent of a broad spectrum of interests.

Survey results that compare the attitudes of citizens and elites in the

Soviet successor states are consistent with this argument (Braumoeller 1997).

Moreover, these constraints are readily apparent to other states and

cannot be manipulated by leaders. Thus, democracies send credible

signals to other states of an aversion to using force. These signals

allow democratic states to avoid conflicts with one another, but they

may attract aggression from nondemocratic states. Democracies may be

pressured to respond to such aggression—perhaps even

preemptively—through the use of force. Also as described in (Gelpi & Griesdorf 2001),

studies have argued that when democratic leaders do choose to escalate

international crises, their threats are taken as highly credible, since

there must be a relatively large public opinion for these actions. In

disputes between liberal states, the credibility of their bargaining

signals allows them to negotiate a peaceful settlement before

mobilization.

An explanation based on game theory

similar to the last two above is that the participation of the public

and the open debate send clear and reliable information regarding the

intentions of democracies to other states. In contrast, it is difficult

to know the intentions of nondemocratic leaders, what effect concessions

will have, and if promises will be kept. Thus there will be mistrust

and unwillingness to make concessions if at least one of the parties in a

dispute is a nondemocracy (Levy & Razin 2004).

The risk factors for certain types of state have, however,

changed since Kant's time. In the quote above, Kant points to the lack

of popular support for war – first that the populace will directly or

indirectly suffer in the event of war – as a reason why republics will

not tend to go to war. The number of American troops killed or maimed

versus the number of Iraqi soldiers and civilians maimed and killed in

the American-Iraqi conflict is indicative. This may explain the

relatively great willingness of democratic states to attack weak

opponents: the Iraq war was, initially at least, highly popular in the

United States. The case of the Vietnam War

might, nonetheless, indicate a tipping point where publics may no

longer accept continuing attrition of their soldiers (even while

remaining relatively indifferent to the much higher loss of life on the

part of the populations attacked).

Coleman (2002) uses economic cost-benefit analysis to reach

conclusions similar to Kant's. Coleman examines the polar cases of

autocracy and liberal democracy. In both cases, the costs of war are

assumed to be borne by the people. In autocracy, the autocrat receives

the entire benefits of war, while in a liberal democracy the benefits

are dispersed among the people. Since the net benefit to an autocrat

exceeds the net benefit to a citizen of a liberal democracy, the

autocrat is more likely to go to war. The disparity of benefits and

costs can be so high that an autocrat can launch a welfare-destroying

war when his net benefit exceeds the total cost of war. Contrarily, the

net benefit of the same war to an individual in a liberal democracy can

be negative so that he would not choose to go to war. This disincentive

to war is increased between liberal democracies through their

establishment of linkages, political and economic, that further raise

the costs of war between them. Therefore, liberal democracies are less

likely to go war, especially against each other. Coleman further

distinguishes between offensive and defensive wars and finds that

liberal democracies are less likely to fight defensive wars that may

have already begun due to excessive discounting of future costs.

Criticism

There are several logically distinguishable classes of criticism (Pugh 2005).

Note that they usually apply to no wars or few MIDs between

democracies, not to little systematic violence in established

democracies.

Statistical significance

One study (Schwartz & Skinner 2002)

has argued that there have been as many wars between democracies as one

would expect between any other couple of states. However, its authors

include wars between young and dubious democracies, and very small wars.

Others (Spiro 1994), (Gowa 1999), (Small & Singer 1976)

state that, although there may be some evidence for democratic peace,

the data sample or the time span may be too small to assess any

definitive conclusions. For example, Gowa finds evidence for democratic

peace to be insignificant before 1939, because of the too small number

of democracies, and offers an alternate explanation for the following

period (see the section on Realist Explanations). Gowa's use of statistics has been criticized, with several other studies and reviews finding different or opposing results (Gelpi & Griesdorf 2001), (Ray 2003). However, this can be seen as the longest-lasting criticism to the theory; as noted earlier, also some supporters (Wayman 1998)

agree that the statistical sample for assessing its validity is limited

or scarce, at least if only full-scale wars are considered.

According to one study, (Ray 2003)

which uses a rather restrictive definition of democracy and war, there

were no wars between jointly democratic couples of states in the period

from 1816 to 1992. Assuming a purely random distribution of wars between

states, regardless of their democratic character, the predicted number

of conflicts between democracies would be around ten. So, Ray argues

that the evidence is statistically significant, but that it is still

conceivable that, in the future, even a small number of inter-democratic

wars would cancel out such evidence.

Peace comes before democracy

Douglas

M. Gibler and Andrew Owsiak in their study argued peace almost always

comes before democracy and that states do not develop democracy until

all border disputes have been settled. These studies indicate that there

is strong evidence that peace causes democracy but little evidence that

democracy causes peace (Gibler & Owsiak 2017). Azar Gat

(2017) argues that it is not democracy in itself that leads to peace

but other aspects of modernization, such as economic prosperity and

lower population growth.

The hypothesis that peace causes democracy is supported by psychological and cultural theories. Christian Welzel's human empowerment theory posits that existential security leads to emancipative cultural values and support for a democratic political organization (Welzel 2013). This is in agreement with theories based on evolutionary psychology.

Wars against non-democracies

Several

studies fail to confirm that democracies are less likely to wage war

than autocracies if wars against non-democracies are included (Cashman 2013, Chapt. 5).

Definitions, methodology and data

Some

authors criticize the definition of democracy by arguing that states

continually reinterpret other states' regime types as a consequence of

their own objective interests and motives, such as economic and security

concerns (Rosato 2003). For example, one study (Oren 1995)

reports that Germany was considered a democratic state by Western

opinion leaders at the end of the 19th century; yet in the years

preceding World War I, when its relations with the United States, France

and Britain started deteriorating, Germany was gradually reinterpreted

as an autocratic state, in absence of any actual regime change. Shimmin (Shimmin 1999) moves a similar criticism regarding the western perception of Milosevic's Serbia between 1989 and 1999. Rummel (Rummel 1999)

replies to this criticism by stating that, in general, studies on

democratic peace do not focus on other countries' perceptions of

democracy; and in the specific case of Serbia, by arguing that the

limited credit accorded by western democracies to Milosevic in the early

'90s did not amount to a recognition of democracy, but only to the

perception that possible alternative leaders could be even worse.

Some democratic peace researchers have been criticized for post hoc

reclassifying some specific conflicts as non-wars or political systems

as non-democracies without checking and correcting the whole data set

used similarly. Supporters and opponents of the democratic peace agree

that this is bad use of statistics, even if a plausible case can be made

for the correction (Bremer 1992), (Gleditsch 1995), (Gowa 1999). A military affairs columnist of the newspaper Asia Times has summarized the above criticism in a journalist's fashion describing the theory as subject to the no true Scotsman problem: exceptions are explained away as not being between "real" democracies or "real" wars.

Some democratic peace researchers require that the executive

result from a substantively contested election. This may be a

restrictive definition: For example, the National Archives of the United

States notes that "For all intents and purposes, George Washington was unopposed for election as President, both in 1789 and 1792". (Under the original provisions for the Electoral College,

there was no distinction between votes for President and

Vice-President: each elector was required to vote for two distinct

candidates, with the runner-up to be Vice-President. Every elector cast

one of his votes for Washington,

John Adams received a majority of the other votes; there were several

other candidates: so the election for Vice President was contested.)

Spiro (1994) made several other criticisms of the statistical

methods used. Russett (1995) and a series of papers described by Ray

(2003) responded to this, for example with different methodology.

Sometimes the datasets used have also been criticized. For

example, some authors have criticized the Correlates of War data for not

including civilian deaths in the battle deaths count, especially in

civil wars (Sambanis 2001).

Weeks and Cohen (2006) argue that most fishing disputes, which include

no deaths and generally very limited threats of violence, should be

excluded even from the list of military disputes. Gleditsch (2004) made

several criticisms to the Correlates of War data set, and produced a

revised set of data. Maoz and Russett (1993) made several criticisms to

the Polity I and II data sets, which have mostly been addressed in later

versions. These criticisms are generally considered minor issues.

The most comprehensive critique points out that "democracy" is

rarely defined, never refers to substantive democracy, is unclear about

causation, has been refuted in more than 100 studies, fails to account

for some 200 deviant cases, and has been promoted ideologically to

justify one country seeking to expand democracy abroad (Haas 2014).

Most studies treat the complex concept of "democracy" is a bivariate

variable rather than attempting to dimensionalize the concept. Studies

also fail to take into account the fact that there are dozens of types

of democracy, so the results are meaningless unless articulated to a

particular type of democracy or claimed to be true for all types, such

as consociational or economic democracy, with disparate datasets.

Microfoundations

Recent

work into the democratic norms explanations shows that the

microfoundations on which this explanation rest do not find empirical

support. Within most earlier studies, the presence of liberal norms in

democratic societies and their subsequent influence on the willingness

to wage war was merely assumed, never measured. Moreover, it was never

investigated whether or not these norms are absent within other

regime-types. Two recent studies measured the presence of liberal norms

and investigated the assumed effect of these norms on the willingness to

wage war. The results of both studies show that liberal democratic

norms are not only present within liberal democracies, but also within

other regime-types. Moreover, these norms show are not of influence on

the willingness to attack another state during an interstate conflict at

the brink of war (Bakker 2017, 2018).

Limited consequences

The peacefulness may have various limitations and qualifiers and may not actually mean very much in the real world.

Democratic peace researchers do in general not count as wars

conflicts which do not kill a thousand on the battlefield; thus they

exclude for example the bloodless Cod Wars. However, as noted earlier, research has also found a peacefulness between democracies when looking at lesser conflicts.

Democracies were involved in more colonial and imperialistic wars

than other states during the 1816–1945 period. On the other hand, this

relation disappears if controlling for factors like power and number of

colonies. Liberal democracies have less of these wars than other states

after 1945. This might be related to changes in the perception of

non-European peoples, as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Ravlo & Gleditsch 2000).

Related to this is the human rights violations committed against native people,

sometimes by liberal democracies. One response is that many of the

worst crimes were committed by nondemocracies, like in the European

colonies before the nineteenth century, in King Leopold II of Belgium's privately owned Congo Free State, and in Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union. The United Kingdom abolished slavery in British territory in 1833, immediately after the Reform Act 1832

had significantly enlarged the franchise. (Of course, the abolition of

the slave trade had been enacted in 1807; and many DPT supporters would

deny that the UK was a liberal democracy in 1833 when examining

interstate wars.)

Hermann and Kegley (1995) argue that interventions between

democracies are more likely to happen than projected by an expected

model. They further argue (1996) that democracies are more likely to

intervene in other liberal states than against countries that are

non-democracies. Finally, they argue that these interventions between

democracies have been increasing over time and that the world can expect

more of these interventions in the future (Hermann & Kegley, 1995,

1996, 1997). The methodology used has been criticized and more recent

studies have found opposing results (Gleditsch, Christiansen & Hegre 2004).

Rummel argues that the continuing increase in democracy worldwide will soon lead to an end to wars and democide, possibly around or even before the middle of this century. The fall of Communism

and the increase in the number of democratic states were accompanied by

a sudden and dramatic decline in total warfare, interstate wars, ethnic wars, revolutionary wars, and the number of refugees and displaced persons. One report claims that the two main causes of this decline in warfare are the end of the Cold War itself and decolonization; but also claims that the three Kantian factors have contributed materially.

Historical periods

Economic

historians Joel Mokyr and Hans-Joachim Voth argue that democratic

states may have been more vulnerable to conquest because the rulers in

those states were too heavily constrained. Absolutist rulers in other

states could however operate more effectively (Mokyr & Voth 2010, pp. 25–26).

Academic relevance and derived studies

Democratic

peace theory is a well established research field with more than a

hundred authors having published articles about it (Rummel n.d.). Several peer-reviewed studies mention in their introduction that most researchers accept the theory as an empirical fact.

Imre Lakatos

suggested that what he called a "progressive research program" is

better than a "degenerative" one when it can explain the same phenomena

as the "degenerative" one, but is also characterized by growth of its

research field and the discovery of important novel facts. In contrast,

the supporters of the "degenerative" program do not make important new

empirical discoveries, but instead mostly apply adjustments to their

theory in order to defend it from competitors. Some researchers argue

that democratic peace theory is now the "progressive" program in

international relations. According to these authors, the theory can

explain the empirical phenomena previously explained by the earlier

dominant research program, realism in international relations;

in addition, the initial statement that democracies do not, or rarely,

wage war on one another, has been followed by a rapidly growing

literature on novel empirical regularities. (Ray 2003), (Chernoff 2004), (Harrison 2005).

Other examples are several studies finding that democracies are

more likely to ally with one another than with other states, forming

alliances which are likely to last longer than alliances involving

nondemocracies (Ray 2003); several studies including (Weart 1998)

showing that democracies conduct diplomacy differently and in a more

conciliatory way compared to nondemocracies; one study finding that

democracies with proportional representation are in general more peaceful regardless of the nature of the other party involved in a relationship (Leblang & Chan 2003);

and another study reporting that proportional representation system and

decentralized territorial autonomy is positively associated with

lasting peace in postconflict societies (Binningsbø 2005).

Coup by provoking a war

Many

democracies become non-democratic by war, as being aggressed or as

aggressor (quickly after a coup), sometimes the coup leader worked to

provoke that war.

Schmitt (1922) wrote on how to overrule a Constitution: "Sovereign is he who decides on the exception."

Schmitt

(1927) again on the need for internal (and foreign) enemies because

they are useful to persuade the people not to trust anyone more than the

Leader: “As long as the state is a political entity this requirement

for internal peace compels it in critical situations to decide also upon

the domestic enemy. Every state provides, therefore, some kind of

formula for the declaration of an internal enemy.” Whatever opposition

will be pictured and intended as the actual foreign enemy's puppet.

Other explanations

Political similarity

One

general criticism motivating research of different explanations is that

actually the theory cannot claim that "democracy causes peace", because

the evidence for democracies being, in general, more peaceful is very

slight or non existent; it only can support the claim that "joint

democracy causes peace". According to Rosato (2003), this casts doubts

on whether democracy is actually the cause because, if so, a monadic

effect would be expected.

Perhaps the simplest explanation to such perceived anomaly (but

not the one the Realist Rosato prefers, see the section on Realist

explanations below) is that democracies are not peaceful to each other

because they are democratic, but rather because they are similar.

This line of thought started with several independent observations of

an "Autocratic Peace" effect, a reduced probability of war (obviously no

author claims its absence) between states which are both

non-democratic, or both highly so (Raknerud & Hegre 1997), (Beck & Jackman 1998),

This has led to the hypothesis that democratic peace emerges as a

particular case when analyzing a subset of states which are, in fact,

similar (Werner 2000).

Or, that similarity in general does not solely affect the probability

of war, but only coherence of strong political regimes such as full

democracies and stark autocracies.

Autocratic peace and the explanation based on political

similarity is a relatively recent development, and opinions about its

value are varied. Henderson (2002) builds a model considering political

similarity, geographic distance and economic interdependence as its main

variables, and concludes that democratic peace is a statistical

artifact which disappears when the above variables are taken into

account. Werner (2000) finds a conflict reducing effect from political

similarity in general, but with democratic dyads being particularly

peaceful, and noting some differences in behavior between democratic and

autocratic dyads with respect to alliances and power evaluation. Beck,

King and Zeng (2004) use neural networks to show two distinct low

probability zones, corresponding to high democracy and high autocracy.

Petersen (2004) uses a different statistical model and finds that

autocratic peace is not statistically significant, and that the effect

attributed to similarity is mostly driven by the pacifying effect of

joint democracy. Ray (2005) similarly disputes the weight of the

argument on logical grounds, claiming that statistical analysis on

"political similarity" uses a main variable which is an extension of

"joint democracy" by linguistic redefinition, and so it is expected that

the war reducing effects are carried on in the new analysis. Bennett

(2006) builds a direct statistical model based on a triadic

classification of states into "democratic", "autocratic" and "mixed". He

finds that autocratic dyads have a 35% reduced chance of going into any

type of armed conflict with respect to a reference mixed dyad.

Democratic dyads have a 55% reduced chance. This effect gets stronger

when looking at more severe conflicts; for wars (more than 1000 battle

deaths), he estimates democratic dyads to have an 82% lower risk than

autocratic dyads. He concludes that autocratic peace exists, but

democratic peace is clearly stronger. However, he finds no relevant

pacifying effect of political similarity, except at the extremes of the

scale.

To summarize a rather complex picture, there are no less than four possible stances on the value of this criticism:

- Political similarity, plus some complementary variables, explains everything. Democratic peace is a statistical artifact. Henderson subscribes to this view.

- Political similarity has a pacifying effect, but democracy makes it stronger. Werner would probably subscribe to this view.

- Political similarity in general has little or no effect, except at the extremes of the democracy-autocracy scale: a democratic peace and an autocratic peace exist separately, with the first one being stronger, and may have different explanations. Bennett holds this view, and Kinsella mentions this as a possibility

- Political similarity has little or no effect and there is no evidence for autocratic peace. Petersen and Ray are among defendants of this view.

Economic factors

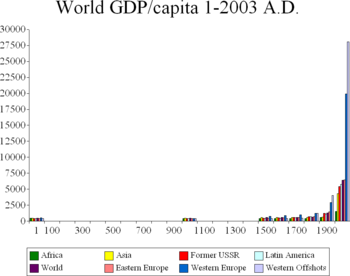

World GDP/capita

1–2003 AD. The increase in the number of democratic nations has

occurred at the same time as the increase in economic wealth.

The capitalist peace, or capitalist peace theory, posits that

according to a given criteria for economic development (capitalism),

developed economies have not engaged in war with each other, and rarely

enter into low-level disputes. These theories have been proposed as an

explanation for the democratic peace by accounting for both democracy

and the peace among democratic nations. The exact nature of the

causality depends upon both the proposed variable and the measure of the

indicator for the concept used.

A majority of researchers on the determinants of democracy agree

that economic development is a primary factor which allows the formation

of a stable and healthy democracy (Hegre, 2003; Weede, 2004). Thus,

some researchers have argued that economic development also plays a

factor in the establishment of peace.

Mousseau argues that a culture of contracting in advanced

market-oriented economies may cause both democracy and peace (2000;

2002; 2003; 2005). These studies indicate that democracy, alone, is an

unlikely cause of the democratic peace. A low level of market-oriented

economic development may hinder development of liberal institutions and

values. Hegre (2000) and Souva (2003) confirmed these expectations.

Mousseau (2005) finds that democracy is a significant factor only when

both democracies have levels of economic development well above the

global median. In fact, the poorest 21% of the democracies studied, and

the poorest 4–5% of current democracies, are significantly more

likely than other kinds of countries to fight each other. Mousseau,

Hegre & Oneal (2003) confirm that if at least one of the democracies

involved has a very low level of economic development, democracy is

ineffective in preventing war; however, they find that when also

controlling for trade, 91% of all the democratic pairs had high enough

development for the pacifying effect of democracy to be important during

the 1885–1992 period and all in 1992. The difference in results of

Mousseau (2005) and Mousseau, Hegre & Oneal (2003) may be due to

sampling: Mousseau (2005) observed only neighboring states where poor

countries actually can fight each other. In fact, fully 89% of

militarized conflicts between less developed countries from 1920 and

2000 were among directly contiguous neighbors (Mousseau 2005,

pp. 68–69). He argues that it is not likely that the results can be

explained by trade: Because developed states have large economies, they

do not have high levels of trade interdependence (2005:70 and footnote

5; Mousseau, Hegre & Oneal 2003:283). In fact, the correlation of

developed democracy with trade interdependence is a scant 0.06

(Pearson's r – considered substantively no correlation by statisticians)(2005:77).

Both World Wars

were fought between countries which can be considered economically

developed. Mousseau argues that both Germany and Japan – like the USSR

during the Cold War and Saudi Arabia today – had state-managed economies

and thus lacked his market norms (Mousseau 2002–2003,

p. 29). Hegre (2003) finds that democracy is correlated with civil

peace only for developed countries, and for countries with high levels

of literacy. Conversely, the risk of civil war decreases with

development only for democratic countries.

Gartzke (2005) argues that economic freedom

(a quite different concept from Mousseau's market norms) or financial

dependence (2007) explains the developed democratic peace, and these

countries may be weak on these dimensions too. Rummel (2005) criticizes Gartzke's methodology and argues that his results are invalid.

Several studies find that democracy, more trade causing greater economic interdependence, and membership in more intergovernmental organizations

reduce the risk of war. This is often called the Kantian peace theory

since it is similar to Kant's earlier theory about a perpetual peace; it

is often also called "liberal peace" theory, especially when one

focuses on the effects of trade and democracy. (The theory that free trade can cause peace is quite old and referred to as Cobdenism.)

Many researchers agree that these variables positively affect each

other but each has a separate pacifying effect. For example, in

countries exchanging a substantial amount of trade, economic interest

groups may exist that oppose a reciprocal disruptive war, but in

democracy such groups may have more power, and the political leaders be

more likely to accept their requests. (Russett & Oneal 2001), (Lagazio & Russett 2004), (Oneal & Russett 2004).

Weede (2004) argues that the pacifying effect of free trade and

economic interdependence may be more important than that of democracy,

because the former affects peace both directly and indirectly, by

producing economic development and ultimately, democracy. Weede also

lists some other authors supporting this view. However, some recent

studies find no effect from trade but only from democracy (Goenner 2004), (Kim & Rousseau 2005).

None of the authors listed argues that free trade alone causes

peace. Even so, the issue of whether free trade or democracy is more

important in maintaining peace may have potentially significant

practical consequences, for example on evaluating the effectiveness of

applying economic sanctions and restrictions to autocratic countries.

It was Michael Doyle (1983,

1997) who reintroduced Kant's three articles into democratic peace

theory. He argued that a pacific union of liberal states has been

growing for the past two centuries. He denies that a pair of states will

be peaceful simply because they are both liberal democracies; if that

were enough, liberal states would not be aggressive towards weak

non-liberal states (as the history of American relations with Mexico

shows they are). Rather, liberal democracy is a necessary condition for

international organization and hospitality (which are Kant's other two

articles)—and all three are sufficient to produce peace. Other Kantians

have not repeated Doyle's argument that all three in the triad must be

present, instead stating that all three reduce the risk of war.

Immanuel Wallerstein

has argued that it is the global capitalist system that creates shared

interests among the dominant parties, thus inhibiting potentially

harmful belligerence (Satana 2010, p. 231).

Negri and Hardt

take a similar stance, arguing that the intertwined network of

interests in the global capitalism leads to the decline of individual nation states, and the rise of a global Empire

which has no outside, and no external enemies. As a result, they write,

"The era of imperialist, interimperialist, and anti-imperialist wars is

over. (...) we have entered the era of minor and internal conflicts.

Every imperial war is a civil war, a police action" (Hardt & Negri 2000).

Other explanations

Many studies, as those discussed in (Ray 1998), (Ray 2005), (Oneal & Russett 2004),

supporting the theory have controlled for many possible alternative

causes of the peace. Examples of factors controlled for are geographic

distance, geographic contiguity, power status, alliance ties,

militarization, economic wealth and economic growth, power ratio, and

political stability. These studies have often found very different

results depending on methodology and included variables, which has

caused criticism. It should be noted that DPT does not state democracy

is the only thing affecting the risk of military conflict. Many of the

mentioned studies have found that other factors are also important.

However, a common thread in most results is an emphasis on the

relationship between democracy and peace.

Several studies have also controlled for the possibility of reverse causality from peace to democracy. For example, one study (Reuveny & Li 2003)

supports the theory of simultaneous causation, finding that dyads

involved in wars are likely to experience a decrease in joint democracy,

which in turn increases the probability of further war. So they argue

that disputes between democratizing or democratic states should be

resolved externally at a very early stage, in order to stabilize the

system. Another study (Reiter 2001)

finds that peace does not spread democracy, but spreading democracy is

likely to spread peace. A different kind of reverse causation lies in

the suggestion that impending war could destroy or decrease democracy,

because the preparation for war might include political restrictions,

which may be the cause for the findings of democratic peace. However,

this hypothesis has been statistically tested in a study (Mousseau & Shi 1999)

whose authors find, depending on the definition of the pre-war period,

no such effect or a very slight one. So, they find this explanation

unlikely. Note also that this explanation would predict a monadic

effect, although weaker than the dyadic one.

Weart (1998) argues that the peacefulness appears and disappears

rapidly when democracy appears and disappears. This in his view makes it

unlikely that variables that change more slowly are the explanation.

Weart, however, has been criticized for not offering any quantitative

analysis supporting his claims (Ray 2000).

Wars tend very strongly to be between neighboring states.

Gleditsch (1995) showed that the average distance between democracies is

about 8000 miles, the same as the average distance between all states.

He believes that the effect of distance in preventing war, modified by

the democratic peace, explains the incidence of war as fully as it can

be explained.

Realist explanations

Supporters of realism in international relations

in general argue that not democracy or its absence, but considerations

and evaluations of power, cause peace or war. Specifically, many realist

critics claim that the effect ascribed to democratic, or liberal,

peace, is in fact due to alliance ties between democratic states which

in turn are caused, one way or another, by realist factors.

For example, Farber and Gowa (1995) find evidence for peace

between democracies to be statistically significant only in the period

from 1945 on, and consider such peace an artifact of the Cold War,

when the threat from the communist states forced democracies to ally

with one another. Mearsheimer (1990) offers a similar analysis of the

Anglo-American peace before 1945, caused by the German threat. Spiro

(1994) finds several instances of wars between democracies, arguing that

evidence in favor of the theory might be not so vast as other authors

report, and claims that the remaining evidence consists of peace between

allied states with shared objectives. He acknowledges that democratic

states might have a somewhat greater tendency to ally with one another,

and regards this as the only real effect of democratic peace. Rosato

(2003) argues that most of the significant evidence for democratic peace

has been observed after World War II; and that it has happened within a

broad alliance, which can be identified with NATO and its satellite

nations, imposed and maintained by American dominance.

One of the main points in Rosato's argument is that, although never

engaged in open war with another liberal democracy during the Cold War,

the United States intervened openly or covertly in the political affairs

of democratic states several times, for example in the Chilean coup of 1973, the 1953 coup in Iran and 1954 coup in Guatemala; in Rosato's view, these interventions show the United States' determination to maintain an "imperial peace".

The most direct counter arguments to such criticisms have been

studies finding peace between democracies to be significant even when

controlling for "common interests" as reflected in alliance ties (Gelpi & Griesdorf 2001), (Ray 2003).

Regarding specific issues, Ray (1998) objects that explanations based

on the Cold War should predict that the Communist bloc would be at peace

within itself also, but exceptions include the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, the Cambodian-Vietnamese War, and the Sino-Vietnamese War.

Ray also argues that the external threat did not prevent conflicts in

the Western bloc when at least one of the involved states was a

nondemocracy, such as the Turkish Invasion of Cyprus (against Greek Junta supported Cypriot Greeks), the Falklands War, and the Football War. Also, one study (Ravlo & Gleditsch 2000)

notes that the explanation "goes increasingly stale as the post-Cold

War world accumulates an increasing number of peaceful dyad-years

between democracies". Rosato's argument about American dominance has

also been criticized for not giving supporting statistical evidence (Slantchev, Alexandrova & Gartzke 2005).

Some realist authors also criticize in detail the explanations

first by supporters of democratic peace, pointing to supposed

inconsistencies or weaknesses.

Rosato (2003) criticizes most explanations to how democracy might

cause peace. Arguments based on normative constraints, he argues, are

not consistent with the fact that democracies do go to war no less than

other states, thus violating norms preventing war; for the same reason

he refutes arguments based on the importance of public opinion.

Regarding explanations based on greater accountability of leaders, he

finds that historically autocratic leaders have been removed or punished

more often than democratic leaders when they get involved in costly

wars. Finally, he also criticizes the arguments that democracies treat

each other with trust and respect even during crises; and that democracy

might be slow to mobilize its composite and diverse groups and

opinions, hindering the start of a war, drawing support from other

authors. Another realist, Layne (1994), analyzes the crises and brinkmanship

that took place between non-allied democratic great powers, during the

relatively brief period when such existed. He finds no evidence either

of institutional or cultural constraints against war; indeed, there was

popular sentiment in favor of war on both sides. Instead, in all cases,

one side concluded that it could not afford to risk that war at that

time, and made the necessary concessions.

Rosato's objections have been criticized for claimed logical and

methodological errors, and for being contradicted by existing

statistical research (Kinsella 2005).

Russett (1995) replies to Layne by re-examining some of the crises

studied in his article, and reaching different conclusions; Russett

argues that perceptions of democracy prevented escalation, or played a

major role in doing so. Also, a recent study (Gelpi & Griesdorf 2001)

finds that, while in general the outcome of international disputes is

highly influenced by the contenders' relative military strength, this is

not true if both contenders are democratic states; in this case the

authors find the outcome of the crisis to be independent of the military

capabilities of contenders, which is contrary to realist expectations.

Finally, both the realist criticisms here described ignore new possible

explanations, like the game-theoretic one discussed below (Risse n.d.).

Nuclear deterrent

A different kind of realist criticism (see Jervis 2002

for a discussion) stresses the role of nuclear weapons in maintaining

peace. In realist terms, this means that, in the case of disputes

between nuclear powers, respective evaluation of power might be

irrelevant because of Mutual assured destruction preventing both sides from foreseeing what could be reasonably called a "victory". The 1999 Kargil War between India and Pakistan has been cited as a counterexample to this argument (Page Fortna 2004).

Some supporters of the democratic peace do not deny that realist factors are also important (Russett 1995).

Research supporting the theory has also shown that factors such as

alliance ties and major power status influence interstate conflict

behavior (Ray 2003).

Influence

The democratic peace theory has been extremely divisive among political scientists. It is rooted in the idealist and classical liberalist traditions and is opposed to the previously dominant theory of realism. However, democratic peace theory has come to be more widely accepted and has in some democracies effected policy change.

In the United States, presidents from both major parties have expressed support for the theory. In his 1994 State of the Union address, then-President Bill Clinton, a member of the Democratic Party,

said: "Ultimately, the best strategy to ensure our security and to

build a durable peace is to support the advance of democracy elsewhere.

Democracies don't attack each other" (Clinton 2000). In a 2004 press conference, then-President George W. Bush, a member of the Republican Party,

said: "And the reason why I'm so strong on democracy is democracies

don't go to war with each other. And the reason why is the people of

most societies don't like war, and they understand what war means....

I've got great faith in democracies to promote peace. And that's why I'm

such a strong believer that the way forward in the Middle East, the

broader Middle East, is to promote democracy."

In a 1999 speech, Chris Patten, the then-European Commissioner

for External Relations, said: "Inevitable because the EU was formed

partly to protect liberal values, so it is hardly surprising that we

should think it appropriate to speak out. But it is also sensible for

strategic reasons. Free societies tend not to fight one another or to be

bad neighbours" (Patten 1999). The A Secure Europe in a Better World, European Security Strategy states: "The best protection for our security is a world of well-governed democratic states." Tony Blair has also claimed the theory is correct.

As justification for initiating war

Some

fear that the democratic peace theory may be used to justify wars

against nondemocracies in order to bring lasting peace, in a democratic crusade (Chan 1997, p. 59). Woodrow Wilson in 1917 asked Congress to declare war against Imperial Germany, citing Germany's sinking of American ships due to unrestricted submarine warfare and the Zimmermann telegram,

but also stating that "A steadfast concert for peace can never be

maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations" and "The world

must be made safe for democracy." R. J. Rummel is a notable proponent of war for the purpose of spreading democracy, based on this theory.

Some point out that the democratic peace theory has been used to justify the 2003 Iraq War, others argue that this justification was used only after the war had already started (Russett 2005).

Furthermore, Weede (2004) has argued that the justification is

extremely weak, because forcibly democratizing a country completely

surrounded by non-democracies, most of which are full autocracies, as

Iraq was, is at least as likely to increase the risk of war as it is to

decrease it (some studies show that dyads formed by one democracy and

one autocracy are the most warlike, and several find that the risk of

war is greatly increased in democratizing countries surrounded by

nondemocracies).

According to Weede, if the United States and its allies wanted to adopt

a rationale strategy of forced democratization based on democratic

peace, which he still does not recommend, it would be best to start

intervening in countries which border with at least one or two stable

democracies, and expand gradually. Also, research shows that attempts to

create democracies by using external force has often failed. Gleditsch,

Christiansen and Hegre (2004) argue that forced democratization by

interventionism may initially have partial success, but often create an

unstable democratizing country, which can have dangerous consequences in

the long run. Those attempts which had a permanent and stable success,

like democratization in Austria, West Germany and Japan after World War II,

mostly involved countries which had an advanced economic and social

structure already, and implied a drastic change of the whole political

culture. Supporting internal democratic movements and using diplomacy

may be far more successful and less costly. Thus, the theory and related

research, if they were correctly understood, may actually be an

argument against a democratic crusade (Weart 1998), (Owen 2005), (Russett 2005).

Michael Haas has written perhaps the most trenchant critique of a hidden normative agenda (Haas 1997).

Among the points raised: Due to sampling manipulation, the research

creates the impression that democracies can justifiably fight

nondemocracies, snuff out budding democracies, or even impose democracy.

And due to sloppy definitions, there is no concern that democracies

continue undemocratic practices yet remain in the sample as if pristine

democracies.

This criticism is confirmed by David Keen (2006) who finds that almost all historical attempts to impose democracy by violent means have failed.

According to Azar Gat's War in Human Civilization, there are

several related and independent factors that contribute to democratic

societies being more peaceful than other forms of governments (Gat 2006):

- Wealth and comfort: Increased prosperity in democratic societies has been associated with peace because civilians are less willing to endure hardship of war and military service due to a more luxurious life at home than in pre-modern times. Increased wealth has worked to decrease war through comfort (Gat 2006, pp. 597–598).

- Metropolitan service society: The majority of army recruits come from the country side or factory workers. Many believe that these types of people are suited for war. But as technology progressed the army turned more towards advanced services in information that rely more on computerized data which urbanized people are recruited more for this service (Gat 2006, pp. 600–602).

- Sexual revolution: The availability of sex due to the pill and women joining the labor market could be another factor that has led to less enthusiasm for men to go to war. Young men are more reluctant leave behind the pleasures of life for the rigors and chastity of the army (Gat 2006, pp. 603-604).

- Fewer young males: There is greater life expectancy which leads to fewer young males. Young males are the most aggressive and the ones that join the army the most. With fewer younger males in developed societies could help explain more pacificity (Gat 2006, pp. 604–605).

- Fewer Children per Family (lower fertility rate): During pre modern times it was always hard for families to lose a child but in modern times it has become more difficult due to more families having only one or two children. It has become even harder for parents to risk the loss of a child in war. However, Gat recognizes that this argument is a difficult one because during pre modern times the life expectancy was not high for children and bigger families were necessary (Gat 2006, pp. 605–606).

- Women's franchise: Women are less overtly aggressive than men. Therefore, women are less inclined to serious violence and do not support it as much as men do. In liberal democracies women have been able to influence the government by getting elected. Electing more women could have an effect on whether liberal democracies take a more aggressive approach on certain issues (Gat 2006, pp. 606-607).

- Nuclear weapons: Nuclear weapons could be the reason for not having a great power war. Many believe that a nuclear war would result in mutually assured destruction (MAD) which means that both countries involved in a nuclear war have the ability to strike the other until both sides are wiped out. This results in countries not wanting to strike the other for fear of being wiped out (Gat 2006, pp. 608–609).

Related theories

The European peace