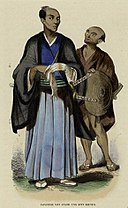

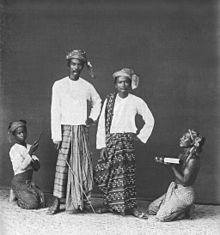

From top-left to bottom-right or from top to bottom (mobile): a samurai and his servant, c. 1846; Udvary The Slave Trader, painting by Géza Udvary, unknown date; The Bower Garden, painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1859

A social class is a set of subjectively defined concepts in the social sciences and political theory centered on models of social stratification in which people are grouped into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes.

"Class" is a subject of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, anthropologists and social historians. However, there is not a consensus on a definition of "class" and the term has a wide range of sometimes conflicting meanings. In common parlance, the term "social class" is usually synonymous with "socio-economic class", defined as "people having the same social, economic, cultural, political or educational status", e.g., "the working class"; "an emerging professional class". However, academics distinguish social class and socioeconomic status, with the former referring to one's relatively stable sociocultural background and the latter referring to one's current social and economic situation and consequently being more changeable over time.

The precise measurements of what determines social class in society has varied over time. Karl Marx thought "class" was defined by one's relationship to the means of production (their relations of production). His simple understanding of classes in modern capitalist society are the proletariat, those who work but do not own the means of production; and the bourgeoisie, those who invest and live off the surplus generated by the proletariat's operation of the means of production. This contrasts with the view of the sociologist Max Weber, who argued "class" is determined by economic position, in contrast to "social status" or "Stand" which is determined by social prestige rather than simply just relations of production. The term "class" is etymologically derived from the Latin classis, which was used by census takers to categorize citizens by wealth in order to determine military service obligations.

In the late 18th century, the term "class" began to replace classifications such as estates, rank and orders as the primary means of organizing society into hierarchical divisions. This corresponded to a general decrease in significance ascribed to hereditary characteristics and increase in the significance of wealth and income as indicators of position in the social hierarchy.

History

Burmese nobles and servants

Historically, social class and behavior were sometimes laid down in

law. For example, permitted mode of dress in sometimes and places was

strictly regulated, with sumptuous dressing only for the high ranks of

society and aristocracy, whereas sumptuary laws stipulated the dress and jewelry appropriate for a person's social rank and station.

Theoretical models

Definitions of social classes reflect a number of sociological perspectives, informed by anthropology, economics, psychology and sociology. The major perspectives historically have been Marxism and structural functionalism. The common stratum model of class divides society into a simple hierarchy of working class, middle class and upper class.

Within academia, two broad schools of definitions emerge: those aligned

with 20th-century sociological stratum models of class society and

those aligned with the 19th-century historical materialist economic models of the Marxists and anarchists.

Another distinction can be drawn between analytical concepts of

social class, such as the Marxist and Weberian traditions, as well as

the more empirical traditions such as socio-economic status approach,

which notes the correlation of income, education and wealth with social

outcomes without necessarily implying a particular theory of social

structure.

Marxist

[Classes are] large groups of people differing from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined system of social production, by their relation (in most cases fixed and formulated in law) to the means of production, by their role in the social organization of labor, and, consequently, by the dimensions of the share of social wealth of which they dispose and the mode of acquiring it. —Vladimir Lenin, A Great Beginning on June 1919

For Marx, class is a combination of objective and subjective factors. Objectively, a class shares a common relationship to the means of production. Subjectively, the members will necessarily have some perception ("class consciousness")

of their similarity and common interest. Class consciousness is not

simply an awareness of one's own class interest but is also a set of

shared views regarding how society should be organized legally,

culturally, socially and politically. These class relations are

reproduced through time.

In Marxist theory, the class structure of the capitalist mode of production is characterized by the conflict between two main classes: the bourgeoisie, the capitalists who own the means of production and the much larger proletariat (or "working class") who must sell their own labour power (wage labour). This is the fundamental economic structure of work and property, a state of inequality that is normalized and reproduced through cultural ideology.

Marxists explain the history of "civilized" societies in terms of a war of classes between those who control production and those who produce the goods or services in society. In the Marxist view of capitalism, this is a conflict between capitalists (bourgeoisie)

and wage-workers (the proletariat). For Marxists, class antagonism is

rooted in the situation that control over social production necessarily

entails control over the class which produces goods—in capitalism this

is the exploitation of workers by the bourgeoisie.

Furthermore, "in countries where modern civilisation has become

fully developed, a new class of petty bourgeois has been formed".

"An industrial army of workmen, under the command of a capitalist,

requires, like a real army, officers (managers) and sergeants (foremen,

over-lookers) who, while the work is being done, command in the name of

the capitalist".

Marx makes the argument that, as the bourgeoisie reach a point of

wealth accumulation, they hold enough power as the dominant class to

shape political institutions and society according to their own

interests. Marx then goes on to claim that the non-elite class, owing to

their large numbers, have the power to overthrow the elite and create

an equal society.

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx himself argued that it was the goal of the proletariat itself to displace the capitalist system with socialism, changing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then developing into a future communist

society in which: "the free development of each is the condition for

the free development of all". This would mark the beginning of a classless society in which human needs rather than profit would be motive for production. In a society with democratic control and production for use, there would be no class, no state and no need for financial and banking institutions and money.

Weberian

Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification

that saw social class as emerging from an interplay between "class",

"status" and "power". Weber believed that class position was determined

by a person's relationship to the means of production, while status or

"Stand" emerged from estimations of honor or prestige.

Weber derived many of his key concepts on social stratification

by examining the social structure of many countries. He noted that

contrary to Marx's theories, stratification was based on more than

simply ownership of capital.

Weber pointed out that some members of the aristocracy lack economic

wealth yet might nevertheless have political power. Likewise in Europe,

many wealthy Jewish families lacked prestige and honor because they were

considered members of a "pariah group".

- Class: A person's economic position in a society. Weber differs from Marx in that he does not see this as the supreme factor in stratification. Weber noted how managers of corporations or industries control firms they do not own.

- Status: A person's prestige, social honor or popularity in a society. Weber noted that political power was not rooted in capital value solely, but also in one's status. Poets and saints, for example, can possess immense influence on society with often little economic worth.

- Power: A person's ability to get their way despite the resistance of others. For example, individuals in state jobs, such as an employee of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or a member of the United States Congress, may hold little property or status, but they still hold immense power.

Great British Class Survey

On April 2, 2013, the results of a survey conducted by BBC Lab UK developed in collaboration with academic experts and slated to be published in the journal Sociology were published online. The results released were based on a survey of 160,000 residents of the United Kingdom most of whom lived in England and described themselves as "white". Class was defined and measured according to the amount and kind of economic, cultural and social resources reported. Economic capital was defined as income and assets; cultural capital as amount and type of cultural interests and activities; and social capital as the quantity and social status of their friends, family and personal and business contacts. This theoretical framework was developed by Pierre Bourdieu who first published his theory of social distinction in 1979.

Common three-stratum model

Today,

concepts of social class often assume three general categories: a very

wealthy and powerful upper class that owns and controls the means of

production; a middle class of professional workers, small business owners and low-level managers; and a lower class, who rely on low-paying wage jobs for their livelihood and often experience poverty.

Upper class

A symbolic image of three orders of feudal society in Europe prior to the French Revolution, which shows the rural third estate carrying the clergy and the nobility

The upper class is the social class composed of those who are rich,

well-born, powerful, or a combination of those. They usually wield the

greatest political power. In some countries, wealth alone is sufficient

to allow entry into the upper class. In others, only people who are born

or marry into certain aristocratic bloodlines are considered members of

the upper class and those who gain great wealth through commercial

activity are looked down upon by the aristocracy as nouveau riche.

In the United Kingdom, for example, the upper classes are the

aristocracy and royalty, with wealth playing a less important role in

class status. Many aristocratic peerages or titles have seats attached

to them, with the holder of the title (e.g. Earl of Bristol) and his

family being the custodians of the house, but not the owners. Many of

these require high expenditures, so wealth is typically needed. Many

aristocratic peerages and their homes are parts of estates, owned and

run by the title holder with moneys generated by the land, rents or

other sources of wealth. However, in the United States where there is no

aristocracy or royalty, the upper class status belongs to the extremely

wealthy, the so-called "super-rich", though there is some tendency even

in the United States for those with old family wealth to look down on

those who have earned their money in business, the struggle between New

Money and Old Money.

The upper class is generally contained within the richest one or

two percent of the population. Members of the upper class are often born

into it and are distinguished by immense wealth which is passed from

generation to generation in the form of estates.

Middle class

The middle class is the most contested of the three categories, the

broad group of people in contemporary society who fall

socio-economically between the lower and upper classes.

One example of the contest of this term is that in the United States

"middle class" is applied very broadly and includes people who would

elsewhere be considered working class. Middle-class workers are sometimes called "white-collar workers".

Theorists such as Ralf Dahrendorf

have noted the tendency toward an enlarged middle class in modern

Western societies, particularly in relation to the necessity of an

educated work force in technological economies. Perspectives concerning globalization and neocolonialism, such as dependency theory, suggest this is due to the shift of low-level labour to developing nations and the Third World.

Lower class

In the United States the lowest stratum of the working class, the underclass, often lives in urban areas with low-quality civil services

Lower class (occasionally described as working class) are those employed in low-paying wage jobs with very little economic security. The term "lower class" also refers to persons with low income.

The working class is sometimes separated into those who are employed but lacking financial security (the "working poor") and an underclass—those who are long-term unemployed and/or homeless, especially those receiving welfare from the state. The latter is analogous to the Marxist term "lumpenproletariat". Members of the working class are sometimes called blue-collar workers.

Consequences of class position

A

person's socioeconomic class has wide-ranging effects. It can impact

the schools they are able to attend, their health, the jobs open to

them, who they may marry and their treatment by police and the courts.

Angus Deaton and Anne Case have analyzed the mortality rates

related to the group of white, middle-aged Americans between the ages of

45 and 54 and its relation to class. There has been a growing number of

suicides and deaths by substance abuse in this particular group of middle-class Americans.

This group also has been recorded to have an increase in reports of

chronic pain and poor general health. Deaton and Case came to the

conclusion from these observations that because of the constant stress

that these white, middle aged Americans feel fighting poverty and

wavering between the middle and lower classes, these strains have taken a

toll on these people and affected their whole bodies.

Social classifications can also determine the sporting activities

that such classes take part in. It is suggested that those of an upper

social class are more likely to take part in sporting activities,

whereas those of a lower social background are less likely to

participate in sport. However, upper-class people tend to not take part

in certain sports that have been commonly known to be linked with the

lower class.

Education

A

person's social class has a significant impact on their educational

opportunities. Not only are upper-class parents able to send their

children to exclusive schools that are perceived to be better, but in

many places state-supported schools for children of the upper class are

of a much higher quality than those the state provides for children of

the lower classes. This lack of good schools is one factor that perpetuates the class divide across generations.

In 1977, British cultural theorist Paul Willis

published a study titled "Learning to Labour" in which he investigated

the connection between social class and education. In his study, he

found that a group of working-class schoolchildren had developed an

antipathy towards the acquisition of knowledge as being outside their

class and therefore undesirable, perpetuating their presence in the

working class.

Health and nutrition

A person's social class has a significant impact on their physical health, their ability to receive adequate medical care and nutrition and their life expectancy.

Lower-class people experience a wide array of health problems as a

result of their economic status. They are unable to use health care as

often and when they do it is of lower quality, even though they

generally tend to experience a much higher rate of health issues.

Lower-class families have higher rates of infant mortality, cancer, cardiovascular disease

and disabling physical injuries. Additionally, poor people tend to work

in much more hazardous conditions, yet generally have much less (if

any) health insurance provided for them, as compared to middle- and

upper-class workers.

Employment

The

conditions at a person's job vary greatly depending on class. Those in

the upper-middle class and middle class enjoy greater freedoms in their

occupations. They are usually more respected, enjoy more diversity and

are able to exhibit some authority.

Those in lower classes tend to feel more alienated and have lower work

satisfaction overall. The physical conditions of the workplace differ

greatly between classes. While middle-class workers may "suffer

alienating conditions" or "lack of job satisfaction", blue-collar

workers are more apt to suffer alienating, often routine, work with

obvious physical health hazards, injury and even death.

A recent United Kingdom government study has suggested that a

"glass floor" exists in British society which prevents those who are

less able, but who come from wealthier backgrounds, from slipping down

the social ladder. This is due to the fact that those from wealthier

backgrounds have more opportunities available to them. In fact, the

article shows that less able, better-off kids are 35% more likely to

become high earners than bright poor kids.

Class conflict

Class conflict, frequently referred to as "class warfare" or "class

struggle", is the tension or antagonism which exists in society due to

competing socioeconomic interests and desires between people of different classes.

For Marx, the history of class society was a history of class

conflict. He pointed to the successful rise of the bourgeoisie and the

necessity of revolutionary violence—a heightened form of class

conflict—in securing the bourgeoisie rights that supported the

capitalist economy.

Marx believed that the exploitation and poverty inherent in

capitalism were a pre-existing form of class conflict. Marx believed

that wage labourers would need to revolt to bring about a more equitable distribution of wealth and political power.

Classless society

"Classless society" refers to a society in which no one is born into a social class. Distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience and achievement in such a society.

Since these distinctions are difficult to avoid, advocates of a classless society (such as anarchists and communists)

propose various means to achieve and maintain it and attach varying

degrees of importance to it as an end in their overall

programs/philosophy.

Relationship between ethnicity and class

Equestrian portrait of Empress Elizabeth of Russia with a Moor servant

Race

and other large-scale groupings can also influence class standing. The

association of particular ethnic groups with class statuses is common in

many societies. As a result of conquest or internal ethnic

differentiation, a ruling class is often ethnically homogenous and

particular races or ethnic groups in some societies are legally or

customarily restricted to occupying particular class positions. Which

ethnicities are considered as belonging to high or low classes varies

from society to society.

In modern societies, strict legal links between ethnicity and class have been drawn, such as in apartheid, the caste system in Africa, the position of the Burakumin in Japanese society and the casta system in Latin America.