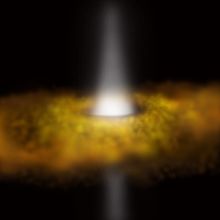

Image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope of what may be gas accreting onto a black hole in the elliptical galaxy NGC 4261

An accretion disk is a structure (often a circumstellar disk) formed by diffuse material in orbital motion around a massive central body. The central body is typically a star. Friction

causes orbiting material in the disk to spiral inward towards the

central body. Gravitational and frictional forces compress and raise the

temperature of the material, causing the emission of electromagnetic radiation. The frequency range of that radiation depends on the central object's mass. Accretion disks of young stars and protostars radiate in the infrared; those around neutron stars and black holes in the X-ray part of the spectrum. The study of oscillation modes in accretion disks is referred to as diskoseismology.

Manifestations

Accretion disks are a ubiquitous phenomenon in astrophysics; active galactic nuclei, protoplanetary disks, and gamma ray bursts all involve accretion disks. These disks very often give rise to astrophysical jets coming from the vicinity of the central object. Jets are an efficient way for the star-disk system to shed angular momentum without losing too much mass.

The most spectacular accretion disks found in nature are those of active galactic nuclei and of quasars,

which are thought to be massive black holes at the center of galaxies.

As matter enters the accretion disc, it follows a trajectory called a tendex line,

which describes an inward spiral. This is because particles rub and

bounce against each other in a turbulent flow, causing frictional

heating which radiates energy away, reducing the particles' angular

momentum, allowing the particle to drift inwards, driving the inward

spiral. The loss of angular momentum manifests as a reduction in

velocity; at a slower velocity, the particle wants to adopt a lower

orbit. As the particle falls to this lower orbit, a portion of its

gravitational potential energy is converted to increased velocity and

the particle gains speed. Thus, the particle has lost energy even though

it is now travelling faster than before; however, it has lost angular

momentum. As a particle orbits closer and closer, its velocity

increases, as velocity increases frictional heating increases as more

and more of the particle's potential energy (relative to the black hole)

is radiated away; the accretion disk of a black hole is hot enough to

emit X-rays just outside the event horizon. The large luminosity of quasars is believed to be a result of gas being accreted by supermassive black holes. Elliptical accretion disks formed at tidal disruption of stars can be typical in galactic nuclei and quasars.

Accretion process can convert about 10 percent to over 40 percent of

the mass of an object into energy as compared to around 0.7 percent for nuclear fusion processes. In close binary systems the more massive primary component evolves faster and has already become a white dwarf, a neutron star, or a black hole, when the less massive companion reaches the giant state and exceeds its Roche lobe.

A gas flow then develops from the companion star to the primary.

Angular momentum conservation prevents a straight flow from one star to

the other and an accretion disk forms instead.

Accretion disks surrounding T Tauri stars or Herbig stars are called protoplanetary disks because they are thought to be the progenitors of planetary systems. The accreted gas in this case comes from the molecular cloud out of which the star has formed rather than a companion star.

Artist's view of a star with accretion disk

Accretion disk physics

Artist's conception of a black hole drawing matter from a nearby star, forming an accretion disk.

In the 1940s, models were first derived from basic physical principles.

In order to agree with observations, those models had to invoke a yet

unknown mechanism for angular momentum redistribution. If matter is to

fall inwards it must lose not only gravitational energy but also lose angular momentum.

Since the total angular momentum of the disk is conserved, the angular

momentum loss of the mass falling into the center has to be compensated

by an angular momentum gain of the mass far from the center. In other

words, angular momentum should be transported outwards for matter to accrete. According to the Rayleigh stability criterion,

where represents the angular velocity of a fluid element and its distance to the rotation center,

an accretion disk is expected to be a laminar flow. This prevents the existence of a hydrodynamic mechanism for angular momentum transport.

On one hand, it was clear that viscous stresses would eventually

cause the matter towards the center to heat up and radiate away some of

its gravitational energy. On the other hand, viscosity itself was not enough to explain the transport of angular momentum to the exterior parts of the disk. Turbulence-enhanced

viscosity was the mechanism thought to be responsible for such

angular-momentum redistribution, although the origin of the turbulence

itself was not well understood. The conventional -model (discussed below) introduces an adjustable parameter describing the effective increase of viscosity due to turbulent eddies within the disk. In 1991, with the rediscovery of the magnetorotational instability

(MRI), S. A. Balbus and J. F. Hawley established that a weakly

magnetized disk accreting around a heavy, compact central object would

be highly unstable, providing a direct mechanism for angular-momentum

redistribution.

α-Disk Model

Shakura and Sunyaev (1973)

proposed turbulence in the gas as the source of an increased viscosity.

Assuming subsonic turbulence and the disk height as an upper limit for

the size of the eddies, the disk viscosity can be estimated as where is the sound speed, is the FWHM of the disk, and is a free parameter between zero (no accretion) and approximately one. In a turbulent medium , where is the velocity of turbulent cells relative to the mean gas motion, and is the size of the largest turbulent cells, which is estimated as and , where is the Keplerian orbital angular velocity, is the radial distance from the central object of mass . By using the equation of hydrostatic equilibrium, combined with conservation of angular momentum and assuming that the disk is thin, the equations of disk structure may be solved in terms of the parameter. Many of the observables depend only weakly on , so this theory is predictive even though it has a free parameter.

Using Kramers' law for the opacity it is found that

where and are the mid-plane temperature and density respectively. is the accretion rate, in units of , is the mass of the central accreting object in units of a solar mass, , is the radius of a point in the disk, in units of , and , where is the radius where angular momentum stops being transported inwards.

The Shakura-Sunyaev α-Disk model is both thermally and viscously unstable. An alternative model, known as the -disk, which is stable in both senses assumes that the viscosity is proportional to the gas pressure . In the standard Shakura-Sunyaev model, viscosity is assumed to be proportional to the total pressure since

.

The Shakura-Sunyaev model assumes that the disk is in local

thermal equilibrium, and can radiate its heat efficiently. In this case,

the disk radiates away the viscous heat, cools, and becomes

geometrically thin. However, this assumption may break down. In the

radiatively inefficient case, the disk may "puff up" into a torus

or some other three-dimensional solution like an Advection Dominated

Accretion Flow (ADAF). The ADAF solutions usually require that the

accretion rate is smaller than a few percent of the Eddington limit. Another extreme is the case of Saturn's rings,

where the disk is so gas poor that its angular momentum transport is

dominated by solid body collisions and disk-moon gravitational

interactions. The model is in agreement with recent astrophysical

measurements using gravitational lensing.

Magnetorotational instability

HH-30, a Herbig–Haro object surrounded by an accretion disk

Balbus and Hawley (1991)

proposed a mechanism which involves magnetic fields to generate the

angular momentum transport. A simple system displaying this mechanism is

a gas disk in the presence of a weak axial magnetic field. Two radially

neighboring fluid elements will behave as two mass points connected by a

massless spring, the spring tension playing the role of the magnetic

tension. In a Keplerian disk the inner fluid element would be orbiting

more rapidly than the outer, causing the spring to stretch. The inner

fluid element is then forced by the spring to slow down, reduce

correspondingly its angular momentum causing it to move to a lower

orbit. The outer fluid element being pulled forward will speed up,

increasing its angular momentum and move to a larger radius orbit. The

spring tension will increase as the two fluid elements move further

apart and the process runs away.

It can be shown that in the presence of such a spring-like tension the Rayleigh stability criterion is replaced by

Most astrophysical disks do not meet this criterion and are therefore

prone to this magnetorotational instability. The magnetic fields

present in astrophysical objects (required for the instability to occur)

are believed to be generated via dynamo action.

Magnetic fields and jets

Accretion disks are usually assumed to be threaded by the external magnetic fields present in the interstellar medium.

These fields are typically weak (about few micro-Gauss), but they can

get anchored to the matter in the disk, because of its high electrical conductivity, and carried inward toward the central star. This process can concentrate the magnetic flux around the centre of the disk giving rise to very strong magnetic fields. Formation of powerful astrophysical jets along the rotation axis of accretion disks requires a large scale poloidal magnetic field in the inner regions of the disk.

Such magnetic fields may be advected inward from the interstellar

medium or generated by a magnetic dynamo within the disk. Magnetic

fields strengths at least of order 100 Gauss seem necessary for the

magneto-centrifugal mechanism to launch powerful jets. There are

problems, however, in carrying external magnetic flux inward towards the

central star of the disk.

High electric conductivity dictates that the magnetic field is frozen

into the matter which is being accreted onto the central object with a

slow velocity. However, the plasma is not a perfect electric conductor,

so there is always some degree of dissipation. The magnetic field

diffuses away faster than the rate at which it is being carried inward

by accretion of matter.

A simple solution is assuming a viscosity much larger than the magnetic diffusivity

in the disk. However, numerical simulations, and theoretical models,

show that the viscosity and magnetic diffusivity have almost the same

order of magnitude in magneto-rotationally turbulent disks.

Some other factors may possibly affect the advection/diffusion rate:

reduced turbulent magnetic diffusion on the surface layers; reduction of

the Shakura-Sunyaev viscosity by magnetic fields; and the generation of large scale fields by small scale MHD turbulence –a large scale dynamo.

Analytic models of sub-Eddington accretion disks (thin disks, ADAFs)

When

the accretion rate is sub-Eddington and the opacity very high, the

standard thin accretion disk is formed. It is geometrically thin in the

vertical direction (has a disk-like shape), and is made of a relatively

cold gas, with a negligible radiation pressure. The gas goes down on

very tight spirals, resembling almost circular, almost free (Keplerian)

orbits. Thin disks are relatively luminous and they have thermal

electromagnetic spectra, i.e. not much different from that of a sum of

black bodies. Radiative cooling is very efficient in thin disks. The

classic 1974 work by Shakura and Sunyaev on thin accretion disks is one

of the most often quoted papers in modern astrophysics. Thin disks were

independently worked out by Lynden-Bell, Pringle and Rees. Pringle

contributed in the past thirty years many key results to accretion disk

theory, and wrote the classic 1981 review that for many years was the

main source of information about accretion disks, and is still very

useful today.

Simulation by J.A. Marck of optical appearance of Schwarzschild black hole with thin (Keplerian) disk.

A fully general relativistic treatment, as needed for the inner part of the disk when the central object is a black hole, has been provided by Page and Thorne, and used for producing simulated optical images by Luminet and Marck,

in which it is to be noted that, although such a system is

intrinsically symmetric its image is not, because the relativistic

rotation speed needed for centrifugal equilibrium in the very strong

gravitational field near the black hole produces a strong Doppler

redshift on the receding side (taken here to be on the right) whereas

there will be a strong blueshift on the approaching side. It is also to

be noted that due to light bending, the disk appears distorted but is

nowhere hidden by the black hole (in contrast with what is shown in the

misinformed artist's impression presented below).

When the accretion rate is sub-Eddington and the opacity very

low, an ADAF is formed. This type of accretion disk was predicted in

1977 by Ichimaru. Although Ichimaru's paper was largely ignored, some

elements of the ADAF model were present in the influential 1982 ion-tori

paper by Rees, Phinney, Begelman and Blandford.

ADAFs started to be intensely studied by many authors only after their

rediscovery in the mid-1990 by Narayan and Yi, and independently by

Abramowicz, Chen, Kato, Lasota (who coined the name ADAF), and Regev.

Most important contributions to astrophysical applications of ADAFs have

been made by Narayan and his collaborators. ADAFs are cooled by

advection (heat captured in matter) rather than by radiation. They are

very radiatively inefficient, geometrically extended, similar in shape

to a sphere (or a "corona") rather than a disk, and very hot (close to

the virial temperature). Because of their low efficiency, ADAFs are much

less luminous than the Shakura-Sunyaev thin disks. ADAFs emit a

power-law, non-thermal radiation, often with a strong Compton component.

Analytic models of super-Eddington accretion disks (slim disks, Polish doughnuts)

The theory of highly super-Eddington black hole accretion, M>>MEdd, was developed in the 1980s by Abramowicz, Jaroszynski, Paczyński,

Sikora and others in terms of "Polish doughnuts" (the name was coined

by Rees). Polish doughnuts are low viscosity, optically thick, radiation

pressure supported accretion disks cooled by advection.

They are radiatively very inefficient. Polish doughnuts resemble in

shape a fat torus (a doughnut) with two narrow funnels along the

rotation axis. The funnels collimate the radiation into beams with

highly super-Eddington luminosities.

Slim disks (name coined by Kolakowska) have only moderately super-Eddington accretion rates,

M≥MEdd, rather disk-like shapes, and almost thermal spectra.

They are cooled by advection, and are radiatively ineffective. They were

introduced by Abramowicz, Lasota, Czerny and Szuszkiewicz in 1988.

Excretion disk

The

opposite of an accretion disk is an excretion disk where instead of

material accreting from a disk on to a central object, material is

excreted from the center outwards on to the disk. Excretion disks are

formed when stars merge.

![f=\left[1-\left(\frac{R_\star}{R}\right)^{1/2} \right]^{1/4}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2e053781dbfdf610a0e7cfead8b17c202f83f0f6)