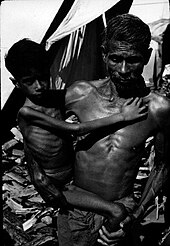

From top to bottom: child victims of famines in

the Netherlands (1944-45), India (1943-44), and Nigeria (1967-70), and a woman and her children during the Great Famine in Ireland (1845–1849)

Some countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, continue to have extreme cases of famine. Since 2010, Africa has been the most affected continent in the world. As of 2017, the United Nations has warned some 20 million are at risk in South Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria and Yemen. The distribution of food has been affected by conflict. Most programmes now direct their aid towards Africa.

Definitions

According

to the United Nations humanitarian criteria, even if there are food

shortages with large numbers of people lacking nutrition, a famine is

declared only when certain measures of mortality, malnutrition and

hunger are met. The criteria are:

- At least 20% of households in an area face extreme food shortages with a limited ability to cope

- The prevalence of acute malnutrition in children exceeds 30%

- The death rate exceeds two people per 10,000 people per day

The declaration of a famine carries no binding obligations on the UN

or member states, but serves to focus global attention on the problem.

History

The cyclical occurrence of famine has been a mainstay of societies engaged in subsistence agriculture

since the dawn of agriculture itself. The frequency and intensity of

famine has fluctuated throughout history, depending on changes in food

demand, such as population growth, and supply-side shifts caused by changing climatic conditions. Famine was first eliminated in Holland and England during the 17th century, due to the commercialization of agriculture and the implementation of improved techniques to increase crop yields.

Decline of famine

In the 16th and 17th century, the feudal system began to break down, and more prosperous farmers began to enclose their own land and improve their yields to sell the surplus crops for a profit. These capitalist landowners paid their labourers with money,

thereby increasing the commercialization of rural society. In the

emerging competitive labour market, better techniques for the

improvement of labour productivity were increasingly valued and

rewarded. It was in the farmer's interest to produce as much as possible

on their land in order to sell it to areas that demanded that product.

They produced guaranteed surpluses of their crop every year if they could.

Subsistence peasants were also increasingly forced to commercialize their activities because of increasing taxes.

Taxes that had to be paid to central governments in money forced the

peasants to produce crops to sell. Sometimes they produced industrial crops,

but they would find ways to increase their production in order to meet

both their subsistence requirements as well as their tax obligations.

Peasants also used the new money to purchase manufactured goods. The

agricultural and social developments encouraging increased food

production were gradually taking place throughout the 16th century, but

took off in the early 17th century.

By the 1590s, these trends were sufficiently developed in the rich and commercialized province of Holland to allow its population to withstand a general outbreak of famine in Western Europe at that time. By that time, the Netherlands had one of the most commercialized agricultural systems in Europe. They grew many industrial crops such as flax, hemp and hops.

Agriculture became increasingly specialized and efficient. The

efficiency of Dutch agriculture allowed for much more rapid urbanization

in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries than anywhere

else in Europe. As a result, productivity and wealth increased, allowing

the Netherlands to maintain a steady food supply.

By 1650, English agriculture had also become commercialized on a

much wider scale. The last peacetime famine in England was in 1623–24.

There were still periods of hunger, as in the Netherlands, but no more

famines ever occurred. Common areas for pasture were enclosed

for private use and large scale, efficient farms were consolidated.

Other technical developments included the draining of marshes, more

efficient field use patterns, and the wider introduction of industrial

crops. These agricultural developments led to wider prosperity in

England and increasing urbanization. By the end of the 17th century, English agriculture was the most productive in Europe.

In both England and the Netherlands, the population stabilized between

1650 and 1750, the same time period in which the sweeping changes to

agriculture occurred. Famine still occurred in other parts of Europe,

however. In East Europe, famines occurred as late as the twentieth century.

Attempts at famine alleviation

Skibbereen, Ireland, during the Great Famine, 1847 illustration by James Mahony for the Illustrated London News

Because of the severity of famine, it was a chief concern for

governments and other authorities. In pre-industrial Europe, preventing

famine, and ensuring timely food supplies, was one of the chief concerns

of many governments, although they were severely limited in their

options due to limited levels of external trade and an infrastructure

and bureaucracy generally too rudimentary to effect real relief. Most

governments were concerned by famine because it could lead to revolt and other forms of social disruption.

By the mid-19th century and the onset of the Industrial Revolution, it became possible for governments to alleviate the effects of famine through price controls, large scale importation of food products from foreign markets, stockpiling, rationing, regulation of production and charity. The Great Famine of 1845

in Ireland was one of the first famines to feature such intervention,

although the government response was often lacklustre. The initial

response of the British government to the early phase of the famine was

"prompt and relatively successful," according to F. S. L. Lyons. Confronted by widespread crop failure in the autumn of 1845, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel purchased £100,000 worth of maize and cornmeal secretly from America. Baring Brothers & Co

initially acted as purchasing agents for the Prime Minister. The

government hoped that they would not "stifle private enterprise" and

that their actions would not act as a disincentive to local relief

efforts. Due to weather conditions, the first shipment did not arrive in

Ireland until the beginning of February 1846. The maize corn was then re-sold for a penny a pound.

In 1846, Peel moved to repeal the Corn Laws, tariffs

on grain which kept the price of bread artificially high. The famine

situation worsened during 1846 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in that

year did little to help the starving Irish; the measure split the

Conservative Party, leading to the fall of Peel's ministry. In March, Peel set up a programme of public works in Ireland.

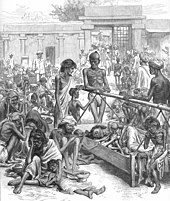

People waiting for famine relief in Bangalore From the Illustrated London News, 1877

Despite this promising start, the measures undertaken by Peel's successor, Lord John Russell,

proved comparatively "inadequate" as the crisis deepened. Russell's

ministry introduced public works projects, which by December 1846

employed some half million Irish and proved impossible to administer.

The government was influenced by a laissez-faire

belief that the market would provide the food needed. It halted

government food and relief works, and turned to a mixture of "indoor"

and "outdoor" direct relief; the former administered in workhouses through the Poor Law, the latter through soup kitchens.

A systematic attempt at creating the necessary regulatory framework for dealing with famine was developed by the British Raj

in the 1880s. In order to comprehensively address the issue of famine,

the British created an Indian Famine commission to recommend steps that

the government would be required to take in the event of a famine.

The Famine Commission issued a series of government guidelines and

regulations on how to respond to famines and food shortages called the

Famine Code. The famine code was also one of the first attempts to

scientifically predict famine in order to mitigate its effects. These

were finally passed into law in 1883 under Lord Ripon.

The Code introduced the first famine scale: three levels of food insecurity were defined: near-scarcity, scarcity, and famine. "Scarcity" was defined as three successive years of crop failure, crop yields

of one-third or one-half normal, and large populations in distress.

"Famine" further included a rise in food prices above 140% of "normal",

the movement of people in search of food, and widespread mortality.

The Commission identified that the loss of wages from lack of

employment of agricultural labourers and artisans were the cause of

famines. The Famine Code applied a strategy of generating employment for

these sections of the population and relied on open-ended public works

to do so.

20th century

During the 20th century, an estimated 70 million people died from famines across the world, of whom an estimated 30 million died during the famine of 1958–61 in China. The other most notable famines of the century included the Bengal famine of 1943, caused by the Japanese occupation of Burma and the policies of Churchill, famines in China in 1928 and 1942, and a sequence of famines in Russia and elsewhere in the Soviet Union, including the Russian famine of 1921–22 and Soviet famine of 1932–1933, caused by the policies of Lenin and Stalin.

Feed The World logo designed for Band Aid.

A few of the great famines of the late 20th century were: the Biafran famine in the 1960s, the Khmer Rouge-caused famine in Cambodia in the 1970s, the North Korean famine of the 1990s and the Ethiopian famine of 1983–85.

The latter event was reported on television reports around the

world, carrying footage of starving Ethiopians whose plight was centered

around a feeding station near the town of Korem. This stimulated the first mass movements to end famine across the world.

BBC newsreader Michael Buerk gave moving commentary of the tragedy on 23 October 1984, which he described as a "biblical famine". This prompted the Band Aid single, which was organized by Bob Geldof and featured more than 20 pop stars. The Live Aid concerts in London and Philadelphia

raised even more funds for the cause. Hundreds of thousands of people

died within one year as a result of the famine, but the publicity Live

Aid generated encouraged Western nations to make available enough

surplus grain to end the immediate hunger crisis in Africa.

21st century

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, an 1887 painting by Viktor Vasnetsov. Depicted from left to right are Death, Famine, War, and Conquest. The Lamb is visible at the top.

Until 2017, worldwide deaths from famine had been falling dramatically. The World Peace Foundation reported that from the 1870s to the 1970s, great famines killed an average of 928,000 people a year.

Since 1980, annual deaths had dropped to an average of 75,000, less

than 10% of what they had been until the 1970s. That reduction was

achieved despite the approximately 150,000 lives lost in the 2011 Somalia famine.

Yet in 2017, the UN officially declared famine had returned to Africa,

with about 20 million people at risk of death from starvation in

Nigeria, in South Sudan, in Yemen, and in Somalia.

Regional history

Africa

- Early history

In the mid-22nd century BC, a sudden and short-lived climatic change

that caused reduced rainfall resulted in several decades of drought in Upper Egypt. The resulting famine and civil strife is believed to have been a major cause of the collapse of the Old Kingdom.

An account from the First Intermediate Period

states, "All of Upper Egypt was dying of hunger and people were eating

their children." In 1680s, famine extended across the entire Sahel, and in 1738 half the population of Timbuktu died of famine. In Egypt, between 1687 and 1731, there were six famines. The famine that afflicted Egypt in 1784 cost it roughly one-sixth of its population. The Maghreb experienced famine and plague in the late 18th century and early 19th century. There was famine in Tripoli in 1784, and in Tunis in 1785.

According to John Iliffe, "Portuguese records of Angola

from the 16th century show that a great famine occurred on average

every seventy years; accompanied by epidemic disease, it might kill

one-third or one-half of the population, destroying the demographic

growth of a generation and forcing colonists back into the river

valleys."

The first documentation of weather in West-Central Africa occurs

around the mid-16th to 17th centuries in areas such as Luanda Kongo,

however, not much data was recorded on the issues of weather and disease

except for a few notable documents. The only records obtained are of

violence between Portuguese and Africans during the Battle of Mbilwa

in 1665. In these documents the Portuguese wrote of African raids on

Portuguese merchants solely for food, giving clear signs of famine.

Additionally, instances of cannibalism

by the African Jaga were also more prevalent during this time frame,

indicating an extreme deprivation of a primary food source.

- Colonial period

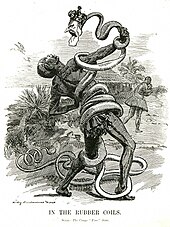

A 1906 Punch cartoon depicting King Leopold II as a rubber vine entangling a Congolese man.

A notable period of famine occurred around the turn of the 20th century in the Congo Free State. In forming this state, Leopold used mass labor camps to finance his empire. This period resulted in the death of up to 10 million Congolese from brutality, disease and famine. Some colonial "pacification" efforts often caused severe famine, notably with the repression of the Maji Maji revolt in Tanganyika

in 1906. The introduction of cash crops such as cotton, and forcible

measures to impel farmers to grow these crops, sometimes impoverished

the peasantry in many areas, such as northern Nigeria, contributing to

greater vulnerability to famine when severe drought struck in 1913.

A large-scale famine occurred in Ethiopia in 1888 and succeeding years, as the rinderpest epizootic, introduced into Eritrea by infected cattle, spread southwards reaching ultimately as far as South Africa.

In Ethiopia it was estimated that as much as 90 percent of the national

herd died, rendering rich farmers and herders destitute overnight. This

coincided with drought associated with an el Nino oscillation, human epidemics of smallpox, and in several countries, intense war. The Ethiopian Great famine that afflicted Ethiopia from 1888 to 1892 cost it roughly one-third of its population. In Sudan the year 1888 is remembered as the worst famine in history, on account of these factors and also the exactions imposed by the Mahdist state.

Records compiled for the Himba recall two droughts from 1910 to 1917. They were recorded by the Himba through a method of oral tradition. From 1910 to 1911 the Himba described the drought as "drought of the omutati seed" also called omangowi, which means the fruit of an unidentified vine that people ate during the time period. From 1914 to 1916 droughts brought katur' ombanda or kari' ombanda which means "the time of eating clothing".

- 20th century

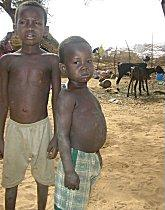

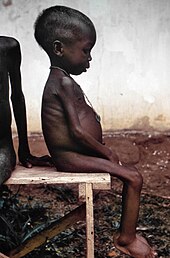

Malnourished children in Niger, during the 2005 famine

For the middle part of the 20th century, agriculturalists, economists

and geographers did not consider Africa to be especially famine prone.

From 1870 to 2010, 87 per cent of deaths from famine occurred in Asia

and Eastern Europe, with only 9.2 per cent in Africa. There were notable counter-examples, such as the famine in Rwanda during World War II and the Malawi famine of 1949, but most famines were localized and brief food shortages.

Although the drought was brief the main cause of death in Rwanda was

due to Belgian prerogatives to acquisition grain from their colony

(Rwanda). The increased grain acquisition was related to WW2. This and

the drought caused 300,000 Rwandans to perish.

From 1967 to 1969 large scale famine occurred in Biafra and Nigeria due to a government blockade of the Breakaway territory.

It is estimated that 1.5 million people died of starvation due to this

famine. Additionally, drought and other government interference with the

food supply caused 500 thousand Africans to perish in Central and West

Africa.

Famine recurred in the early 1970s, when Ethiopia and the west African Sahel suffered drought and famine.

The Ethiopian famine of that time was closely linked to the crisis of

feudalism in that country, and in due course helped to bring about the

downfall of the Emperor Haile Selassie.

The Sahelian famine was associated with the slowly growing crisis of

pastoralism in Africa, which has seen livestock herding decline as a

viable way of life over the last two generations.

A girl during the Nigerian Civil War of the late 1960s. Pictures of the famine caused by Nigerian blockade garnered sympathy for the Biafrans worldwide.

Famines occurred in Sudan in the late-1970s and again in 1990 and 1998. The 1980 famine in Karamoja,

Uganda was, in terms of mortality rates, one of the worst in history.

21% of the population died, including 60% of the infants.

In the 1980s, large scale multilayer drought occurred in the Sudan and

Sahelian regions of Africa. This caused famine because even though the

Sudanese Government believed there was a surplus of grain, there were

local deficits across the region.

In October 1984, television reports describing the Ethiopian famine as "biblical", prompted the Live Aid

concerts in London and Philadelphia, which raised large sums to

alleviate the suffering. A primary cause of the famine (one of the

largest seen in the country) is that Ethiopia (and the surrounding Horn)

was still recovering from the droughts which occurred in the mid-late

1970s. Compounding this problem was the intermittent fighting due to civil war, the government's

lack of organization in providing relief, and hoarding of supplies to

control the population. Ultimately, over 1 million Ethiopians died and

over 22 million people suffered due to the prolonged drought, which

lasted roughly 2 years.

In 1992 Somalia became a war zone with no effective government,

police, or basic services after the collapse of the dictatorship led by Siad Barre and the split of power between warlords. This coincided with a massive drought, causing over 300,000 Somalis to perish.

- Recent years

Laure Souley holds her three-year-old daughter and an infant son at a MSF aide center during the 2005 famine, Maradi Niger

Since the start of the 21st century, more effective early warning and

humanitarian response actions have reduced the number of deaths by

famine markedly. That said, many African countries are not

self-sufficient in food production, relying on income from cash crops to import food. Agriculture in Africa is susceptible to climatic fluctuations, especially droughts which can reduce the amount of food produced locally. Other agricultural problems include soil infertility, land degradation and erosion, swarms of desert locusts, which can destroy whole crops, and livestock diseases. Desertification is increasingly problematic: the Sahara reportedly spreads up to 48 kilometres (30 mi) per year.

The most serious famines have been caused by a combination of drought,

misguided economic policies, and conflict. The 1983–85 famine in

Ethiopia, for example, was the outcome of all these three factors, made

worse by the Communist government's censorship of the emerging crisis.

In Sudan at the same date, drought and economic crisis combined with

denials of any food shortage by the then-government of President Gaafar Nimeiry, to create a crisis that killed perhaps 250,000 people—and helped bring about a popular uprising that overthrew Nimeiry.

Numerous factors make the food security situation in Africa tenuous, including political instability, armed conflict and civil war, corruption

and mismanagement in handling food supplies, and trade policies that

harm African agriculture. An example of a famine created by human rights

abuses is the 1998 Sudan famine. AIDS

is also having long-term economic effects on agriculture by reducing

the available workforce, and is creating new vulnerabilities to famine

by overburdening poor households. On the other hand, in the modern

history of Africa on quite a few occasions famines acted as a major

source of acute political instability. In Africa, if current trends of population growth and soil degradation continue, the continent might

be able to feed just 25% of its population by 2025, according to United Nations University (UNU)'s Ghana-based Institute for Natural Resources in Africa.

Famine-affected areas in the western Sahel belt during the 2012 drought.

Recent famines in Africa include the 2005–06 Niger food crisis, the 2010 Sahel famine and the 2011 East Africa drought, where two consecutive missed rainy seasons precipitated the worst drought in East Africa in 60 years. An estimated 50,000 to 150,000 people are reported to have died during the period. In 2012, the Sahel drought put more than 10 million people in the western Sahel at risk of famine (according to a Methodist Relief & Development Fund (MRDF) aid expert), due to a month-long heat wave.

Today, famine is most widespread in Sub-Saharan Africa, but with exhaustion of food resources, overdrafting of groundwater,

wars, internal struggles, and economic failure, famine continues to be a

worldwide problem with hundreds of millions of people suffering. These famines cause widespread malnutrition and impoverishment. The famine in Ethiopia

in the 1980s had an immense death toll, although Asian famines of the

20th century have also produced extensive death tolls. Modern African

famines are characterized by widespread destitution and malnutrition,

with heightened mortality confined to young children.

- Current initiatives

Against a backdrop of conventional interventions through the state or

markets, alternative initiatives have been pioneered to address the

problem of food security. One pan-African example is the Great Green Wall.

Another example is the "Community Area-Based Development Approach" to

agricultural development ("CABDA"), an NGO programme with the objective

of providing an alternative approach to increasing food security in

Africa. CABDA proceeds through specific areas of intervention such as

the introduction of drought-resistant crops and new methods of food

production such as agro-forestry. Piloted in Ethiopia in the 1990s it

has spread to Malawi, Uganda, Eritrea and Kenya. In an analysis of the

programme by the Overseas Development Institute,

CABDA's focus on individual and community capacity-building is

highlighted. This enables farmers to influence and drive their own

development through community-run institutions, bringing food security

to their household and region.

The role of African Unity organization

The

organization of African unity and its role in the African crisis has

been interested in the political aspects of the continent, especially

the liberation of the occupied parts of it and the elimination of

racism. The organization has succeeded in this area but the economic

field and development has not succeeded in these fields. African leaders

have agreed to waive the role of their organization in the development

to the United Nations through the Economic Commission for Africa "ECA".

Far East

Chinese officials engaged in famine relief, 19th-century engraving

Chinese scholars had kept count of 1,828 instances of famine from

108 BC to 1911 in one province or another—an average of close to one

famine per year.

From 1333 to 1337 a terrible famine killed 6 million Chinese. The four

famines of 1810, 1811, 1846, and 1849 are said to have killed no fewer

than 45 million people.

Japan experienced more than 130 famines between 1603 and 1868.

The period from 1850 to 1873 saw, as a result of the Taiping Rebellion, drought, and famine, the population of China drop by over 30 million people. China's Qing Dynasty bureaucracy, which devoted extensive attention to minimizing famines, is credited with averting a series of famines following El Niño-Southern Oscillation-linked

droughts and floods. These events are comparable, though somewhat

smaller in scale, to the ecological trigger events of China's vast

19th-century famines.

Qing China carried out its relief efforts, which included vast

shipments of food, a requirement that the rich open their storehouses to

the poor, and price regulation, as part of a state guarantee of

subsistence to the peasantry (known as ming-sheng).

When a stressed monarchy shifted from state management and direct

shipments of grain to monetary charity in the mid-19th century, the

system broke down. Thus the 1867–68 famine under the Tongzhi Restoration was successfully relieved but the Great North China Famine of 1877–78, caused by drought across northern China, was a catastrophe. The province of Shanxi

was substantially depopulated as grains ran out, and desperately

starving people stripped forests, fields, and their very houses for

food. Estimated mortality is 9.5 to 13 million people.

- Great Leap Forward

The largest famine of the 20th century, and almost certainly of all time, was the 1958–61 Great Leap Forward

famine in China. The immediate causes of this famine lay in Mao

Zedong's ill-fated attempt to transform China from an agricultural

nation to an industrial power in one huge leap. Communist Party cadres

across China insisted that peasants abandon their farms for collective

farms, and begin to produce steel in small foundries, often melting down

their farm instruments in the process. Collectivisation undermined

incentives for the investment of labor and resources in agriculture;

unrealistic plans for decentralized metal production sapped needed

labor; unfavorable weather conditions; and communal dining halls

encouraged overconsumption of available food. Such was the centralized control of information and the intense pressure on party cadres to report only good news—such as production quotas

met or exceeded—that information about the escalating disaster was

effectively suppressed. When the leadership did become aware of the

scale of the famine, it did little to respond, and continued to ban any

discussion of the cataclysm. This blanket suppression of news was so

effective that very few Chinese citizens were aware of the scale of the

famine, and the greatest peacetime demographic disaster of the 20th

century only became widely known twenty years later, when the veil of

censorship began to lift.

The exact number of famine deaths during 1958–61 is difficult to determine, and estimates range from 18 to at least 42 million people, with a further 30 million cancelled or delayed births.

It was only when the famine had wrought its worst that Mao reversed

agricultural collectivisation policies, which were effectively

dismantled in 1978. China has not experienced a famine of the

proportions of the Great Leap Forward since 1961.

- Khmer Rouge

Skulls of Khmer Rouge murder victims at Choeung Ek

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia. The new government was led by Pol Pot,

who desired to turn Cambodia into a communist, agrarian utopia. His

regime emptied the cities, abolished currency and private property, and

forced Cambodia's population into slavery on communal farms. In less

than four years, the Khmer Rouge had executed nearly 1.4 million people,

mostly those believed to be a threat to the new ideology.

Due to the failure of the Khmer Rouge's agrarian reform policies,

Cambodia experienced widespread famine. As many as one million more

died from starvation, disease, and exhaustion resulting from these

policies.

In 1979 Vietnam invaded Cambodia and removed the Khmer Rouge from

power. By that time about one quarter of Cambodia's population had been

killed.

- North Korean famine in the 1990s

Famine struck North Korea in the mid-1990s, set off by unprecedented floods. This autarkic urban,

industrial state depended on massive inputs of subsidised goods,

including fossil fuels, primarily from the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.

When the Soviet collapse and China's marketization switched trade to a

hard currency, full-price basis, North Korea's economy collapsed. The

vulnerable agricultural sector experienced a massive failure in 1995–96,

expanding to full-fledged famine by 1996–99.

Estimates based on the North Korean census suggest that 240,000

to 420,000 people died as a result of the famine and that there were

600,000 to 850,000 unnatural deaths in North Korea from 1993 to 2008. North Korea has not yet regained food self-sufficiency and relies on external food aid from China, Japan, South Korea, Russia and the United States.

While Woo-Cumings have focused on the FAD side of the famine, Moon

argues that FAD shifted the incentive structure of the authoritarian

regime to react in a way that forced millions of disenfranchised people

to starve to death (Moon, 2009).

According to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation

(FAO), North Korea is facing a serious cereal shortfall in 2017 after

the country's crop harvest was diminished as a result of severe drought.

The FAO estimated that early-season production fell by over 30 percent

compared to agricultural output from the previous year, leading to the

country's worst famine since 2001.

- Vietnam

Various famines have occurred in Vietnam. Japanese occupation during World War II caused the Vietnamese Famine of 1945, which caused 2 million deaths, or 10% of the population then. Following the unification of the country after the Vietnam War, Vietnam experienced a food shortage in the 1980s, which prompted many people to flee the country.

India

Owing to its almost entire dependence upon the monsoon rains, India is vulnerable to crop failures, which upon occasion deepen into famine. There were 14 famines in India

between the 11th and 17th centuries (Bhatia, 1985). For example, during

the 1022–1033 Great famines in India entire provinces were depopulated.

Famine in Deccan

killed at least two million people in 1702–1704. B.M. Bhatia believes

that the earlier famines were localised, and it was only after 1860,

during the British rule,

that famine came to signify general shortage of foodgrains in the

country. There were approximately 25 major famines spread through states

such as Tamil Nadu in the south, and Bihar and Bengal in the east during the latter half of the 19th century.

Victims of the Great Famine of 1876–78 in India during British rule, pictured in 1877.

Romesh Chunder Dutt argued as early as 1900, and present-day scholars such as Amartya Sen

agree, that some historic famines were a product of both uneven

rainfall and British economic and administrative policies, which since

1857 had led to the seizure and conversion of local farmland to

foreign-owned plantations, restrictions on internal trade, heavy

taxation of Indian citizens to support British expeditions in

Afghanistan,

inflationary measures that increased the price of food, and substantial

exports of staple crops from India to Britain. (Dutt, 1900 and 1902;

Srivastava, 1968; Sen, 1982; Bhatia, 1985.)

Some British citizens, such as William Digby, agitated for policy reforms and famine relief, but Lord Lytton,

the governing British viceroy in India, opposed such changes in the

belief that they would stimulate shirking by Indian workers. The first,

the Bengal famine of 1770,

is estimated to have taken around 10 million lives—one-third of

Bengal's population at the time. Other notable famines include the Great Famine of 1876–78, in which 6.1 million to 10.3 million people died and the Indian famine of 1899–1900, in which 1.25 to 10 million people died. The famines were ended by the 20th century with the exception of the Bengal famine of 1943 killing an estimated 2.1 million Bengalis during World War II.

The observations of the Famine Commission of 1880 support the

notion that food distribution is more to blame for famines than food

scarcity. They observed that each province in British India, including

Burma, had a surplus of foodgrains, and the annual surplus was 5.16

million tons (Bhatia, 1970). At that time, annual export of rice and

other grains from India was approximately one million tons.

| “ | Population growth worsened the plight of the peasantry. As a result of peace and improved sanitation and health, the Indian population rose from perhaps 100 million in 1700 to 300 million by 1920. While encouraging agricultural productivity, the British also provided economic incentives to have more children to help in the fields. Although a similar population increase occurred in Europe at the same time, the growing numbers could be absorbed by industrialization or emigration to the Americas and Australia. India enjoyed neither an industrial revolution nor an increase in food growing. Moreover, Indian landlords had a stake in the cash crop system and discouraged innovation. As a result, population numbers far outstripped the amount of available food and land, creating dire poverty and widespread hunger. | ” |

| — -Craig A. Lockard, Societies, Networks, and Transitions[72] | ||

The Maharashtra drought in which there were zero deaths and one which

is known for the successful employment of famine prevention policies,

unlike during British rule.

Middle East

A starving woman and child during the Assyrian Genocide. Ottoman Empire, 1915

The Great Persian famine of 1870–1872 is believed to have caused the death of 1.5 million persons (20–25 percent of the population) in Persia (present-day Iran).

In the early 20th century an Ottoman blockade of food being exported to Lebanon

caused a famine which killed up to 450,000 Lebanese (about one-third of

the population). The famine killed more people than the Lebanese Civil War.

The blockade was caused by uprisings in the Syrian region of the Empire

including one which occurred in the 1860s which lead to the massacre of

thousands of Lebanese and Syrian by Ottoman Turks and local Druze.

Europe

- Middle Ages

The Great Famine of 1315–1317

(or to 1322) was the first major food crisis to strike Europe in the

14th century. Millions in northern Europe died over an extended number

of years, marking a clear end to the earlier period of growth and

prosperity during the 11th and 12th centuries.

An unusually cold and wet spring of 1315 led to widespread crop

failures, which lasted until at least the summer of 1317; some regions

in Europe did not fully recover until 1322. Most nobles, cities, and

states were slow to respond to the crisis and when they realized its

severity, they had little success in securing food for their people. In

1315, in Norfolk England, the price of grain soared from 5

shillings/quarter to 20 shillings/quarter.

It was a period marked by extreme levels of criminal activity, disease

and mass death, infanticide, and cannibalism. It had consequences for

Church, State, European society and future calamities to follow in the

14th century. There were 95 famines in medieval Britain, and 75 or more in medieval France. More than 10% of England's population, or at least 500,000 people, may have died during the famine of 1315–1316.

Famine was a very destabilizing and devastating occurrence. The

prospect of starvation led people to take desperate measures. When

scarcity of food became apparent to peasants, they would sacrifice

long-term prosperity for short-term survival. They would kill their draught animals,

leading to lowered production in subsequent years. They would eat their

seed corn, sacrificing next year's crop in the hope that more seed

could be found. Once those means had been exhausted, they would take to

the road in search of food. They migrated to the cities where merchants

from other areas would be more likely to sell their food, as cities had a

stronger purchasing power than did rural areas. Cities also

administered relief programs and bought grain for their populations so

that they could keep order. With the confusion and desperation of the

migrants, crime would often follow them. Many peasants resorted to

banditry in order to acquire enough to eat.

One famine would often lead to difficulties in the following

years because of lack of seed stock or disruption of routine, or perhaps

because of less-available labour. Famines were often interpreted as

signs of God's displeasure. They were seen as the removal, by God, of

His gifts to the people of the Earth. Elaborate religious processions

and rituals were made to prevent God's wrath in the form of famine.

- 16th century

An engraving from Goya's Disasters of War, showing starving women, doubtless inspired by the terrible famine that struck Madrid in 1811–1812.

During the 15th century to the 18th century, famines in Europe became more frequent due to the Little Ice Age. The colder climate resulted in harvest failures and shortfalls that led to a rise in conspiracy theories concerning the causes behind these famines, such as the Pacte de Famine in France.

The 1590s saw the worst famines in centuries across all of

Europe. Famine had been relatively rare during the 16th century. The

economy and population had grown steadily as subsistence populations

tend to when there is an extended period of relative peace (most of the

time). Although peasants in areas of high population density, such as

northern Italy, had learned to increase the yields of their lands

through techniques such as promiscuous culture, they were still quite

vulnerable to famines, forcing them to work their land even more

intensively.

The great famine of the 1590s began a period of famine and

decline in the 17th century. The price of grain, all over Europe was

high, as was the population. Various types of people were vulnerable to

the succession of bad harvests that occurred throughout the 1590s in

different regions. The increasing number of wage labourers in the

countryside were vulnerable because they had no food of their own, and

their meager living was not enough to purchase the expensive grain of a

bad-crop year. Town labourers were also at risk because their wages

would be insufficient to cover the cost of grain, and, to make matters

worse, they often received less money in bad-crop years since the

disposable income of the wealthy was spent on grain. Often, unemployment

would be the result of the increase in grain prices, leading to

ever-increasing numbers of urban poor.

All areas of Europe were badly affected by the famine in these

periods, especially rural areas. The Netherlands was able to escape most

of the damaging effects of the famine, though the 1590s were still

difficult years there. Amsterdam's grain trade with the Baltic guaranteed a food supply.

- 17th century

The years around 1620 saw another period of famine sweep across

Europe. These famines were generally less severe than the famines of

twenty-five years earlier, but they were nonetheless quite serious in

many areas. Perhaps the worst famine since 1600, the great famine in Finland in 1696, killed one-third of the population.

Devastating harvest failures afflicted the northern Italian

economy from 1618 to 1621, and it did not recover fully for centuries.

There were serious famines in the late-1640s and less severe ones in the

1670s throughout northern Italy.

Over two million people died in two famines in France between 1693 and 1710. Both famines were made worse by ongoing wars.

Illustration of starvation in northern Sweden, Swedish famine of 1867-1869

As late as the 1690s, Scotland experienced famine which reduced the population of parts of Scotland by at least 15%.

The Great Famine of 1695–1697 may have killed a third of the Finnish population. and roughly 10% of Norway's population. Death rates rose in Scandinavia between 1740 and 1800 as the result of a series of crop failures. For instance, the Finnish famine of 1866–1868 killed 15% of the population.

- 18th century

The period of 1740–43 saw frigid winters and summer droughts, which led to famine across Europe and a major spike in mortality. The winter 1740–41 was unusually cold, possibly because of volcanic activity.

According to Scott and Duncan (2002), "Eastern Europe experienced

more than 150 recorded famines between AD 1500 and 1700 and there were

100 hunger years and 121 famine years in Russia between AD 971 and

1974."

The Great Famine, which lasted from 1770 until 1771, killed about one tenth of Czech lands' population, or 250,000 inhabitants, and radicalised countrysides leading to peasant uprisings.

There were sixteen good harvests and 111 famine years in northern Italy from 1451 to 1767. According to Stephen L. Dyson and Robert J. Rowland, "The Jesuits of Cagliari

[in Sardinia] recorded years during the late 1500s "of such hunger and

so sterile that the majority of the people could sustain life only with

wild ferns and other weeds"... During the terrible famine of 1680, some

80,000 persons, out of a total population of 250,000, are said to have

died, and entire villages were devastated..."

According to Bryson (1974), there were thirty-seven famine years in Iceland between 1500 and 1804. In 1783 the volcano Laki in south-central Iceland

erupted. The lava caused little direct damage, but ash and sulphur

dioxide spewed out over most of the country, causing three-quarters of

the island's livestock to perish. In the following famine, around ten

thousand people died, one-fifth of the population of Iceland. [Asimov,

1984, 152–53]

- 19th century

Depiction of victims of the Great Famine in Ireland, 1845–1849

Other areas of Europe have known famines much more recently. France saw famines as recently as the 19th century. The Great Famine

in Ireland, 1846–1851, caused by the failure of the potato crop over a

few years, resulted in 1,000,000 dead and another 2,000,000 refugees

fleeing to Britain, Australia and the United States.

- 20th century

Famine still occurred in Eastern Europe during the 20th century. Droughts and famines in Imperial Russia

are known to have happened every 10 to 13 years, with average droughts

happening every 5 to 7 years. Russia experienced eleven major famines

between 1845 and 1922, one of the worst being the famine of 1891–92. The Russian famine of 1921–22 killed an estimated 5 million.

Victims of the Russian famine of 1921–22 during the Russian Civil War

Famines continued in the Soviet era, the most notorious being the Holodomor in various parts of the country, especially the Volga, and the Ukrainian and northern Kazakh SSR's during the winter of 1932–1933. The Soviet famine of 1932–1933 is nowadays reckoned to have cost an estimated 6 million lives. The last major famine in the USSR happened in 1947 due to the severe drought and the mismanagement of grain reserves by the Soviet government.

The Hunger Plan,

i.e. the Nazi plan to starve large sections of the Soviet population,

caused the deaths of many. The Russian Academy of Sciences in 1995

reported civilian victims in the USSR at German hands, including Jews,

totalled 13.7 million dead, 20% of the 68 million persons in the

occupied USSR. This included 4.1 million famine and disease deaths in

occupied territory. There were an additional estimated 3 million famine

deaths in areas of the USSR not under German occupation.

The 872 days of the Siege of Leningrad

(1941–1944) caused unparalleled famine in the Leningrad region through

disruption of utilities, water, energy and food supplies. This resulted

in the deaths of about one million people.

Famine even struck in Western Europe during the Second World War. In the Netherlands, the Hongerwinter of 1944 killed approximately 30,000 people. Some other areas of Europe also experienced famine at the same time.

Latin America

Malnourished child during Brazil's 1877–78 Grande Seca (Great Drought).

The pre-Columbian Americans often dealt with severe food shortages and famines. The persistent drought around 850 AD coincided with the collapse of Classic Maya civilization, and the famine of One Rabbit (AD 1454) was a major catastrophe in Mexico.

Brazil's 1877–78 Grande Seca (Great Drought), the worst in Brazil's history, caused approximately half a million deaths. The one from 1915 was devastating too.

In 2019, The New York Times reported children dying of hunger in Venezuela, caused by government policies.

Oceania

Easter Island

was hit by a great famine between the 15th and 18th centuries. Hunger

and subsequent cannibalism was caused by overpopulation and depletion of

natural resources as a result of deforestation, partly because work on

megalithic monuments required a lot of wood.

There are other documented episodes of famine in various islands of Polynesia, such as occurred in Kau, Hawaii in 1868.

According to Daniel Lord Smail, "'Famine cannibalism' was until recently a regular feature of life in the islands of the Massim near New Guinea and of some other societies of Southeast Asia and the Pacific."

Risk of future famine

The Guardian reports that in 2007 approximately 40% of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.

If current trends of soil degradation continue in Africa, the continent

might be able to feed just 25% of its population by 2025, according to UNU's Ghana-based Institute for Natural Resources in Africa. As of late 2007, increased farming for use in biofuels, along with world oil prices at nearly $100 a barrel,

has pushed up the price of grain used to feed poultry and dairy cows

and other cattle, causing higher prices of wheat (up 58%), soybean (up

32%), and maize (up 11%) over the year. In 2007 Food riots have taken place in many countries across the world. An epidemic of stem rust, which is destructive to wheat and is caused by race Ug99, has in 2007 spread across Africa and into Asia.

Beginning in the 20th century, nitrogen fertilizers, new pesticides, desert farming,

and other agricultural technologies began to be used to increase food

production, in part to combat famine. Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution

influenced agriculture] world grain production increased by 250%.

Developed nations have shared these technologies with developing nations

with a famine problem. However, as early as 1995, there were signs that

these new developments may contribute to the decline of arable land

(e.g. persistence of pesticides leading to soil contamination, salt accumulation due to irrigation, erosion).

Lake Chad in a 2001 satellite image, with the actual lake in blue. The lake has shrunk by 95% since the 1960s.

In 1994, David Pimentel, professor of ecology and agriculture at Cornell University,

and Mario Giampietro, senior researcher at the National Research

Institute on Food and Nutrition (INRAN), estimated the maximum U.S. population for a sustainable economy at 200 million.

According to geologist Dale Allen Pfeiffer, coming decades could see rising food prices without relief and massive starvation on a global level. Water deficits, which are already spurring heavy grain imports in numerous smaller countries, may soon do the same in larger countries, such as China or India.

The water tables are falling in many countries (including Northern

China, the US, and India) due to widespread overconsumption. Other

countries affected include Pakistan, Iran, and Mexico. This will

eventually lead to water scarcity and cutbacks in grain harvest. Even while overexploiting its aquifers,

China has developed a grain deficit, contributing to the upward

pressure on grain prices. Most of the three billion people projected to

be added worldwide by mid-century will be born in countries already

experiencing water shortages.

After China and India, there is a second tier of smaller

countries with large water deficits – Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Mexico, and

Pakistan. Four of these already import a large share of their grain.

Only Pakistan remains marginally self-sufficient. But with a population

expanding by 4 million a year, it will also soon turn to the world

market for grain. According to a UN climate report, the Himalayan glaciers that are the principal dry-season water sources of Asia's biggest rivers – Ganges, Indus, Brahmaputra, Yangtze, Mekong, Salween and Yellow – could disappear by 2350 as temperatures rise and human demand rises. Approximately 2.4 billion people live in the drainage basin of the Himalayan rivers.

India, China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Myanmar

could experience floods followed by severe droughts in coming decades. In India alone, the Ganges provides water for drinking and farming for more than 500 million people.

Evan Fraser, a geographer at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, explores the ways in which climate change may affect future famines.

To do this, he draws on a range of historic cases where relatively

small environmental problems triggered famines as a way of creating

theoretical links between climate and famine in the future. Drawing on

situations as diverse as the Great Irish Potato Famine,

a series of weather induced famines in Asia during the late 19th

century, and famines in Ethiopia during the 1980s, he concludes there

are three "lines of defense" that protect a community's food security from environmental change. The first line of defense is the agro-ecosystem on which food is produced: diverse ecosystems with well managed soils high in organic matter

tend to be more resilient. The second line of defense is the wealth and

skills of individual households: If those households affected by bad

weather such as drought have savings or skills they may be able to do

all right despite the bad weather. The final line of defense is created

by the formal institutions present in a society. Governments, churches,

or NGOs must be willing and able to mount effective relief efforts.

Pulling this together, Evan Fraser argues that if an ecosystem

is resilient enough, it may be able to withstand weather-related

shocks. But if these shocks overwhelm the ecosystem's line of defense,

it is necessary for the household to adapt using its skills and savings.

If a problem is too big for the family or household, then people must

rely on the third line of defense, which is whether or not the formal

institutions present in a society are able to provide help. Evan Fraser

concludes that in almost every situation where an environmental problem

triggered a famine you see a failure in each of these three lines of

defense.

Hence, understanding how climate change may cause famines in the future

requires combining both an assessment of local socio-economic and

environmental factors along with climate models that predict where bad weather may occur in the future.

Causes

A victim of starvation in besieged Leningrad suffering from dystrophia in 1941.

Definitions of famines are based on three different categories—these

include food supply-based, food consumption-based and mortality-based

definitions. Some definitions of famines are:

- Blix – Widespread food shortage leading to significant rise in regional death rates.

- Brown and Eckholm – Sudden, sharp reduction in food supply resulting in widespread hunger.

- Scrimshaw – Sudden collapse in level of food consumption of large numbers of people.

- Ravallion – Unusually high mortality with unusually severe threat to food intake of some segments of a population.

- Cuny – A set of conditions that occurs when large numbers of people in a region cannot obtain sufficient food, resulting in widespread, acute malnutrition.

Food shortages in a population are caused either by a lack of food or

by difficulties in food distribution; it may be worsened by natural

climate fluctuations and by extreme political conditions related to

oppressive government or warfare. The conventional explanation until

1981 for the cause of famines was the Food availability decline (FAD)

hypothesis. The assumption was that the central cause of all famines was

a decline in food availability.

However, FAD could not explain why only a certain section of the

population such as the agricultural laborer was affected by famines

while others were insulated from famines.

Based on the studies of some recent famines, the decisive role of FAD

has been questioned and it has been suggested that the causal mechanism

for precipitating starvation includes many variables other than just

decline of food availability. According to this view, famines are a

result of entitlements, the theory being proposed is called the "failure

of exchange entitlements" or FEE.

A person may own various commodities that can be exchanged in a market

economy for the other commodities he or she needs. The exchange can

happen via trading or production or through a combination of the two.

These entitlements are called trade-based or production-based

entitlements. Per this proposed view, famines are precipitated due to a

breakdown in the ability of the person to exchange his entitlements.

An example of famines due to FEE is the inability of an agricultural

laborer to exchange his primary entitlement, i.e., labor for rice when

his employment became erratic or was completely eliminated.

According to the Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), global climate change is additionally challenging the Earth's ability to produce food, potentially leading to famine.

Some elements make a particular region more vulnerable to famine. These include poverty, population growth, an inappropriate social infrastructure, a suppressive political regime, and a weak or under-prepared government.

According to a FEWSNET report, "Famines are not natural phenomena, they are catastrophic political failures."

Climate and population pressure

A child suffering extreme starvation in India, 1972

Thomas Malthus's Essay on the Principle of Population has made

popular the theory that many famines are caused by imbalance of food

production compared to the large populations of countries whose population exceeds the regional carrying capacity. However, Professor Alex de Waal, Executive Director of the World Peace Foundation, refutes the Malthus theory, looking instead to political factors as major causes of recent (over the last 150 years) famines. Historically, famines have occurred from agricultural problems such as drought, crop failure, or pestilence. Changing weather patterns, the ineffectiveness of medieval governments in dealing with crises, wars, and epidemic diseases such as the Black Death helped to cause hundreds of famines in Europe during the Middle Ages, including 95 in Britain and 75 in France. In France, the Hundred Years' War, crop failures and epidemics reduced the population by two-thirds.

The failure of a harvest or change in conditions, such as drought, can create a situation whereby large numbers of people continue to live where the carrying capacity of the land has temporarily dropped radically. Famine is often associated with subsistence

agriculture. The total absence of agriculture in an economically strong

area does not cause famine; Arizona and other wealthy regions import

the vast majority of their food, since such regions produce sufficient

economic goods for trade.

Famines have also been caused by volcanism. The 1815 eruption of the Mount Tambora

volcano in Indonesia caused crop failures and famines worldwide and

caused the worst famine of the 19th century. The current consensus of

the scientific community is that the aerosols and dust released into the

upper atmosphere causes cooler temperatures by preventing the sun's

energy from reaching the ground. The same mechanism is theorized to be

caused by very large meteorite impacts to the extent of causing mass

extinctions.

State-sponsored famines

In certain cases, such as the Great Leap Forward in China (which produced the largest famine in absolute numbers), North Korea in the mid-1990s, or Zimbabwe in the early-2000s, famine can occur because of government policy.

The government's forced collectivization of agriculture was one of the main causes of the Soviet famine of 1932–1933.

In 1932, under the rule of the USSR, Ukraine

experienced one of its largest famines when between 2.4 and 7.5 million

peasants died as a result of a state sponsored famine. It was termed

the Holodomor,

suggesting that it was a deliberate campaign of repression designed to

eliminate resistance to collectivization. Forced grain quotas imposed

upon the rural peasants and a brutal reign of terror contributed to the

widespread famine. The Soviet government continued to deny the problem

and it did not provide aid to the victims nor did it accept foreign aid.

Several contemporary scholars dispute the notion that the famine was

deliberately inflicted by the Soviet government.

In 1958 in China, Mao Zedong's Communist Government launched the Great Leap Forward campaign, aimed at rapidly industrializing the country.

The government forcibly took control of agriculture. Barely enough

grain was left for the peasants, and starvation occurred in many rural

areas. Exportation of grain continued despite the famine and the

government attempted to conceal it. While the famine is attributed to

unintended consequences, it is believed that the government refused to

acknowledge the problem, thereby further contributing to the deaths. In

many instances, peasants were persecuted. Between 20 and 45 million

people perished in this famine, making it one of the deadliest famines

to date.

Malawi ended its famine by subsidizing farmers despite the strictures imposed by the World Bank. During the 1973 Wollo Famine in Ethiopia, food was shipped out of Wollo to the capital city of Addis Ababa, where it could command higher prices. In the late-1970s and early-1980s, residents of the dictatorships of Ethiopia and Sudan suffered massive famines, but the democracy of Botswana avoided them, despite also suffering a severe drop in national food production. In Somalia, famine occurred because of a failed state.

The famine in Yemen was a direct result of the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen and the blockade imposed by Saudi Arabia and its allies, including the United States.

According to the UN, 130 children under 5 years of age were dying from

starvation and starvation related diseases every day by the end of 2017,

with 50,000 dead for the year. As of October 2018, half the population

is at risk of famine.

Famines since 1850 by political regime

According to Amartya Sen (1999), "there has never been a famine in a

functioning multiparty democracy". Hasell and Roser have demonstrated

that while there have been a few minor exceptions, famines rarely occur

in democratic systems but are strongly correlated with autocratic and colonial systems.

Famine prevention

A starving child during the 1869 famine in Algeria.

Relief technologies, including immunization, improved public health

infrastructure, general food rations and supplementary feeding for

vulnerable children, has provided temporary mitigation to the mortality

impact of famines, while leaving their economic consequences unchanged,

and not solving the underlying issue of too large a regional population

relative to food production capability. Humanitarian crises may also

arise from genocide campaigns, civil wars, refugee flows and episodes of extreme violence and state collapse, creating famine conditions among the affected populations.

Despite repeated stated intentions by the world's leaders to end

hunger and famine, famine remains a chronic threat in much of Africa,

Eastern Europe, the Southeast, South Asia, and the Middle East. In July

2005, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network labelled Niger with emergency status, as well as Chad, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Somalia and Zimbabwe. In January 2006, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization warned that 11 million people in Somalia,[Kenya, Djibouti and Ethiopia were in danger of starvation due to the combination of severe drought and military conflicts. In 2006, the most serious humanitarian crisis in Africa was in Sudan's region Darfur.

Frances Moore Lappé, later co-founder of the Institute for Food and Development Policy (Food First) argued in Diet for a Small Planet (1971) that vegetarian diets can provide food for larger populations, with the same resources, compared to omnivorous diets.

Noting that modern famines are sometimes aggravated by misguided

economic policies, political design to impoverish or marginalize certain

populations, or acts of war, political economists have investigated the

political conditions under which famine is prevented. Economist Amartya Sen

states that the liberal institutions that exist in India, including

competitive elections and a free press, have played a major role in

preventing famine in that country since independence. Alex de Waal

has developed this theory to focus on the "political contract" between

rulers and people that ensures famine prevention, noting the rarity of

such political contracts in Africa, and the danger that international

relief agencies will undermine such contracts through removing the locus

of accountability for famines from national governments.

A woman, a man and a child, all three dead from starvation. Russia, 1921.

The demographic impacts of famine are sharp. Mortality is

concentrated among children and the elderly. A consistent demographic

fact is that in all recorded famines, male mortality exceeds female,

even in those populations (such as northern India and Pakistan) where

there is a male longevity advantage during normal times. Reasons for

this may include greater female resilience under the pressure of

malnutrition, and possibly female's naturally higher percentage of body

fat. Famine is also accompanied by lower fertility. Famines therefore

leave the reproductive core of a population—adult women—lesser affected

compared to other population categories, and post-famine periods are

often characterized a "rebound" with increased births.

Even though the theories of Thomas Malthus

would predict that famines reduce the size of the population

commensurate with available food resources, in fact even the most severe

famines have rarely dented population growth for more than a few years.

The mortality in China in 1958–61, Bengal in 1943, and Ethiopia in

1983–85 was all made up by a growing population over just a few years.

Of greater long-term demographic impact is emigration: Ireland was

chiefly depopulated after the 1840s famines by waves of emigration.

Food security

Long term measures to improve food security, include investment in modern agriculture techniques, such as fertilizers and irrigation, but can also include strategic national food storage.

World Bank

strictures restrict government subsidies for farmers, and increasing

use of fertilizers is opposed by some environmental groups because of

its unintended consequences: adverse effects on water supplies and

habitat.

Norman Borlaug, father of the Green Revolution, is often credited with saving over a billion people worldwide from starvation.

The effort to bring modern agricultural techniques found in the Western world, such as nitrogen fertilizers and pesticides, to the Indian Sub-continent, called the Green Revolution, resulted in decreases in malnutrition similar to those seen earlier in Western nations. This was possible because of existing infrastructure and institutions that are in short supply in Africa, such as a system of roads or public seed companies that made seeds available. Supporting farmers in areas of food insecurity, through such measures as free or subsidized fertilizers and seeds, increases food harvest and reduces food prices.

The World Bank

and some rich nations press nations that depend on them for aid to cut

back or eliminate subsidized agricultural inputs such as fertilizer, in

the name of privatization even as the United States and Europe extensively subsidized their own farmers.

Relief

There is a growing realization among aid groups that giving cash or

cash vouchers instead of food is a cheaper, faster, and more efficient

way to deliver help to the hungry, particularly in areas where food is

available but unaffordable. The United Nations' World Food Program

(WFP), the biggest non-governmental distributor of food, announced that

it will begin distributing cash and vouchers instead of food in some

areas, which Josette Sheeran, the WFP's executive director, described as

a "revolution" in food aid. The aid agency Concern Worldwide

is piloting a method through a mobile phone operator, Safaricom, which

runs a money transfer program that allows cash to be sent from one part

of the country to another.

However, for people in a drought living a long way from and with limited access to markets, delivering food may be the most appropriate way to help. Fred Cuny

stated that "the chances of saving lives at the outset of a relief

operation are greatly reduced when food is imported. By the time it

arrives in the country and gets to people, many will have died." US Law,

which requires buying food at home rather than where the hungry live,

is inefficient because approximately half of what is spent goes for

transport.

Fred Cuny further pointed out "studies of every recent famine have

shown that food was available in-country—though not always in the

immediate food deficit area" and "even though by local standards the

prices are too high for the poor to purchase it, it would usually be

cheaper for a donor to buy the hoarded food at the inflated price than

to import it from abroad."

Deficient micronutrients can be provided through fortifying foods. Fortifying foods such as peanut butter sachets (see Plumpy'Nut)

have revolutionized emergency feeding in humanitarian emergencies

because they can be eaten directly from the packet, do not require

refrigeration or mixing with scarce clean water, can be stored for years

and, vitally, can be absorbed by extremely ill children.

A Somali boy receiving treatment for malnutrition at a health facility in Hilaweyn during the drought of 2011.

WHO and other sources recommend that malnourished children—and adults who also have diarrhea—drink rehydration solution, and continue to eat, in addition to antibiotics, and zinc supplements.

There is a special oral rehydration solution called ReSoMal which has

less sodium and more potassium than standard solution. However, if the

diarrhea is severe, the standard solution is preferable as the person

needs the extra sodium.

Obviously, this is a judgment call best made by a physician, and using

either solution is better than doing nothing. Zinc supplements often can

help reduce the duration and severity of diarrhea, and Vitamin A can

also be helpful.

The World Health Organization underlines the importance of a person

with diarrhea continuing to eat, with a 2005 publication for physicians

stating: "Food should never be withheld and the child's usual foods should not be diluted. Breastfeeding should always be continued."

Ethiopia

has been pioneering a program that has now become part of the World

Bank's prescribed recipe for coping with a food crisis and had been seen

by aid organizations as a model of how to best help hungry nations.

Through the country's main food assistance program, the Productive

Safety Net Program, Ethiopia has been giving rural residents who are

chronically short of food, a chance to work for food or cash. Foreign

aid organizations like the World Food Program were then able to buy food

locally from surplus areas to distribute in areas with a shortage of

food.

The Green Revolution

was widely viewed as an answer to famine in the 1970s and 1980s.

Between 1950 and 1984, hybrid strains of high-yielding crops transformed

agriculture around the globe and world grain production increased by

250%. Some criticize the process, stating that these new high-yielding crops require more chemical fertilizers and pesticides, which can harm the environment.

Although these high-yielding crops make it technically possible to feed

more people, there are indications that regional food production has

peaked in many world sectors, due to certain strategies associated with

intensive agriculture such as groundwater overdrafting and overuse of pesticides and other agricultural chemicals.

Levels of food insecurity

In modern times, local and political governments and non-governmental organizations

that deliver famine relief have limited resources with which to address

the multiple situations of food insecurity that are occurring

simultaneously. Various methods of categorizing the gradations of food

security have thus been used in order to most efficiently allocate food

relief. One of the earliest were the Indian Famine Codes

devised by the British in the 1880s. The Codes listed three stages of

food insecurity: near-scarcity, scarcity and famine, and were highly

influential in the creation of subsequent famine warning or measurement

systems. The early warning system developed to monitor the region

inhabited by the Turkana people

in northern Kenya also has three levels, but links each stage to a

pre-planned response to mitigate the crisis and prevent its

deterioration.

The experiences of famine relief organizations throughout the

world over the 1980s and 1990s resulted in at least two major

developments: the "livelihoods approach" and the increased use of

nutrition indicators to determine the severity of a crisis. Individuals

and groups in food stressful situations will attempt to cope by

rationing consumption, finding alternative means to supplement income,

etc., before taking desperate measures, such as selling off plots of agricultural

land. When all means of self-support are exhausted, the affected

population begins to migrate in search of food or fall victim to

outright mass starvation. Famine may thus be viewed partially as a social phenomenon, involving markets,

the price of food, and social support structures. A second lesson drawn

was the increased use of rapid nutrition assessments, in particular of

children, to give a quantitative measure of the famine's severity.

Since 2003, many of the most important organizations in famine relief, such as the World Food Programme and the U.S. Agency for International Development,

have adopted a five-level scale measuring intensity and magnitude. The

intensity scale uses both livelihoods' measures and measurements of

mortality and child malnutrition to categorize a situation as food

secure, food insecure, food crisis, famine, severe famine, and extreme

famine. The number of deaths determines the magnitude designation, with

under 1000 fatalities defining a "minor famine" and a "catastrophic

famine" resulting in over 1,000,000 deaths.

Society and culture

Famine personified as an allegory is found in some cultures, e.g. one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in Christian tradition, the fear gorta of Irish folklore, or the Wendigo of Algonquian tradition.