Monument honoring the right to worship, Washington, D.C.

In the United States, freedom of religion is a constitutionally protected right provided in the religion clauses of the First Amendment. Freedom of religion is also closely associated with separation of church and state, a concept advocated by Colonial founders such as Dr. John Clarke, Roger Williams, William Penn and later founding fathers such as James Madison and Thomas Jefferson.

The freedom of religion has changed over time in the United

States and continues to be controversial. Concern over this freedom was a

major topic of George Washington's Farewell Address. Illegal religion was a major cause of the 1890–1891 Ghost Dance War. Starting in 1918, nearly all of the pacifist Hutterites emigrated to Canada when Joseph and Michael Hofer died following torture at Fort Leavenworth for conscientious objection to the draft. Some have since returned, but most Hutterites remain in Canada.

The long term trend has been towards increasing secularization of the government. The remaining state churches where disestablished

in 1820 and teacher-led public school prayer was abolished in 1962, but

the military chaplaincy remains to the present day. Although most

Supreme Court rulings have been accommodationist

towards religion, in recent years there have been attempts to replace

the freedom of religion with the more limited freedom of worship.

Although the freedom of religion includes some form of recognition to

the individual conscience of each citizen with the possibility of conscientious objection to law or policy, the freedom of worship does not.

Controversies surrounding the freedom of religion in the US have

included building places of worship, compulsory speech, prohibited

counseling, compulsory consumerism, workplace, marriage and the family,

the choosing of religious leaders, circumcision of male infants, dress,

education, oaths, praying for sick people, medical care, use of

government lands sacred to Native Americans, the protection of graves,

the bodily use of sacred substances, mass incarceration of clergy,

both animal slaughter for meat and the use of living animals, and

accommodations for employees, prisoners, and military personnel.

Legal and public foundation

The United States Constitution addresses the issue of religion in two places: in the First Amendment, and the Article VI prohibition on religious tests

as a condition for holding public office. The First Amendment prohibits

the Congress from making a law "respecting an establishment of

religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof". This provision was

later expanded to state and local governments, through the Incorporation of the first Amendment.

Colonial precedents

The October 10, 1645, charter of Flushing, Queens,

New York, allowed "liberty of conscience, according to the custom and

practice of Holland without molestation or disturbance from any

magistrate or ecclesiastical minister." However, New Amsterdam

Director-General Peter Stuyvesant

issued an edict prohibiting the harboring of Quakers. On December 27,

1657, the inhabitants of Flushing approved a protest known as The Flushing Remonstrance.

This contained religious arguments even mentioning freedom for "Jews,

Turks, and Egyptians," but ended with a forceful declaration that any

infringement of the town charter would not be tolerated.

Freedom of religion was first applied as a principle in the founding of the colony of Maryland, also founded by the Catholic Lord Baltimore, in 1634. Fifteen years later (1649), an enactment of religious liberty, the Maryland Toleration Act,

drafted by Lord Baltimore, provided: "No person or persons ... shall

from henceforth be any waies troubled, molested or discountenanced for

or in respect of his or her religion nor in the free exercise thereof."

The Maryland Toleration Act was repealed with the assistance of

Protestant assemblymen and a new law barring Catholics from openly

practicing their religion was passed.

In 1657, Lord Baltimore regained control after making a deal with the

colony's Protestants, and in 1658 the Act was again passed by the

colonial assembly. This time, it would last more than thirty years,

until 1692, when after Maryland's Protestant Revolution of 1689, freedom of religion was again rescinded.

In addition in 1704, an Act was passed "to prevent the growth of

Popery in this Province", preventing Catholics from holding political

office. Full religious toleration would not be restored in Maryland until the American Revolution, when Maryland's Charles Carroll of Carrollton signed the American Declaration of Independence.

Rhode Island (1636), Connecticut (1636), New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (1682), founded by Baptist Roger Williams, Congregationalist Thomas Hooker, and Quaker William Penn,

respectively, established the religious freedom in their colonies in

direct opposition to the theocratic government which Separatist Congregationalists (Pilgrim Fathers) and Puritans had enforced in Plymouth Colony (1620) and Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628).

Having fled religious persecution themselves in England, the leaders of

Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colony restricted franchise to members

of their church only, rigorously enforced their own interpretation of

theological law and banished freethinkers such as Roger Williams, who

was actually chased out of Salem., as well as banning Quakers and

Anabaptists.

These colonies became safe havens for persecuted religious minorities.

Catholics and Jews also had full citizenship and free exercise of their

faiths.

Williams, Hooker, Penn, and their friends were firmly convinced that

democracy and freedom of conscience were the will of God. Williams gave

the most profound theological reason: As faith is the free gift of the Holy Spirit, it cannot be forced upon a person. Therefore, strict separation of church and state has to be kept.

Pennsylvania was the only colony that retained unlimited religious

freedom until the foundation of the United States. The inseparable

connection of democracy, freedom of religion, and the other forms of freedom became the political and legal basis of the new nation. In particular, Baptists and Presbyterians demanded vigorously and successfully the disestablishment of the Anglican and Congregational state churches that had existed in most colonies since the seventeenth century.

The First Amendment

In the United States, the religious civil liberties are guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The "Establishment Clause,"

stating that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of

religion," is generally read to prohibit the Federal government from

establishing a national church ("religion") or excessively involving

itself in religion, particularly to the benefit of one religion over

another. Following the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and through the doctrine of incorporation, this restriction is held to be applicable to state governments as well.

The "Free Exercise Clause" states that Congress cannot "prohibit the free exercise" of religious practices. The Supreme Court of the United States

has consistently held, however, that the right to free exercise of

religion is not absolute. For example, in the 19th century, some of the

members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traditionally practiced polygamy, yet in Reynolds v. United States

(1879), the Supreme Court upheld the criminal conviction of one of

these members under a federal law banning polygamy. The Court reasoned

that to do otherwise would set precedent for a full range of religious

beliefs including those as extreme as human sacrifice. The Court stated

that "Laws are made for the government of actions, and while they

cannot interfere with mere religious belief and opinions, they may with

practices." For example, if one were part of a religion that believed in vampirism, the First Amendment would protect one's belief in vampirism, but not the practice.

The Fourteenth Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees the religious civil rights.

Whereas the First Amendment secures the free exercise of religion,

section one of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits discrimination,

including on the basis of religion, by securing "the equal protection of

the laws" for every person:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction there of, are citizens of the United States and of the State where in they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This amendment was cited in Meyer v. Nebraska,

striking down laws which banned education in the German language. These

laws mainly affected church schools teaching in German. Some laws, such

is in Montana, forbade preaching in German during church.

A total ban on teaching German in both public and private schools was

imposed for a time in at least fourteen states, including California, Indiana, Wisconsin, Ohio, Iowa and Nebraska. California's ban lasted into the mid-1920s. German was banned again in California churches in 1941.

The "wall of separation"

Thomas Jefferson wrote that the First Amendment erected a "wall of separation between church and state" likely borrowing the language from Roger Williams, founder of the First Baptist Church in America and the Colony of Rhode Island, who used the phrase in his 1644 book, The Bloody Tenent of Persecution. James Madison, often regarded as the "Father of the Bill of Rights", also often wrote of the "perfect separation", "line of separation", "strongly guarded as is the separation between religion and government in the Constitution of the United States", and "total separation of the church from the state". Madison explicitly credited Martin Luther

as the theorist who "led the way" in providing the proper distinction

between the civil and the ecclesiastical spheres with his doctrine of the two kingdoms.

Controversy rages in the United States between those who wish to

restrict government involvement with religious institutions and remove

religious references from government institutions and property, and

those who wish to loosen such prohibitions. Advocates for stronger separation of church and state, such as already exists in France with the practice of laïcité, emphasize the plurality of faiths and non-faiths in the country, and what they see as broad guarantees of the federal Constitution.

Their opponents emphasize what they see as the largely Christian

heritage and history of the nation (often citing the references to

"Nature's God" and the "Creator" of men in the Declaration of Independence

and the dating of the Constitution with the phrase "in the Year of our

Lord"). Some more socially conservative Christian sects, such as the

Christian Reconstructionist movement, oppose the concept of a "wall of

separation" and prefer a closer relationship between church and state.

Problems also arise in U.S. public schools concerning the teaching and display of religious issues. In various counties, school choice and school vouchers

have been put forward as solutions to accommodate variety in beliefs

and freedom of religion, by allowing individual school boards to choose

between a secular, religious or multi-faith vocation, and allowing

parents free choice among these schools. Critics of American voucher

programs claim that they take funds away from public schools, and that

the amount of funds given by vouchers is not enough to help many middle

and working class parents.

U.S. judges often ordered alcoholic defendants to attend Alcoholics Anonymous

or face imprisonment. However, in 1999, a federal appeals court ruled

this unconstitutional because the A.A. program relies on submission to a

"Higher Power".

Thomas Jefferson also played a large role in the formation of freedom of religion. He created the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which has since been incorporated into the Virginia State Constitution.

Other statements

Inalienable rights

The United States of America was established on foundational principles by the Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; (based on Thomas Jefferson's draft.)

Religious institutions

In 1944, a joint committee of the Federal Council of Churches of Christ in America and the Foreign Missions Conference formulated a "Statement on Religious Liberty"

Religious Liberty shall be interpreted to include freedom to worship according to conscience and to bring up children in the faith of their parents; freedom for the individual to change his religion; freedom to preach, educate, publish and carry on missionary activities; and freedom to organize with others, and to acquire and hold property, for these purposes.

Freedom of religion restoration

Following increasing government involvement in religious matters, Congress passed the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

A number of states then passed corresponding acts (e.g., Missouri passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act).

Treaty of Tripoli

Signed on November 4, 1796, the Treaty of Tripoli was a document that included the following statement:

As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen [Muslims]; and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan [Mohammedan] nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

This treaty was submitted to the Senate and was ratified unanimously

on June 7, 1797, and then signed by President John Adams on June 10,

1797. In accordance with Article VI of the Constitution, on that date this treaty became incorporated as part of "the supreme Law of the Land".

Supreme Court rulings

Jehovah's Witnesses

Since

the 1940s, the Jehovah's Witnesses have often invoked the First

Amendment's freedom of religion clauses to protect their ability to

engage in the proselytizing (or preaching) that is central to their

faith. This series of litigation has helped to define civil liberties

case law in the United States and Canada.

In the United States of America and several other countries, the

legal struggles of the Jehovah's Witnesses have yielded some of the most

important judicial decisions regarding freedom of religion, press and speech. In the United States, many Supreme Court cases involving Jehovah's Witnesses are now landmark decisions of First Amendment

law. Of the 72 cases involving the Jehovah's Witnesses that have been

brought before the U.S. Supreme Court, the Court has ruled in favor of

them 47 times. Even the cases that the Jehovah's Witnesses lost helped

the U.S. to more clearly define the limits of First Amendment rights.

Former Supreme Court Justice Harlan Stone

jokingly suggested "The Jehovah's Witnesses ought to have an endowment

in view of the aid which they give in solving the legal problems of

civil liberties." "Like it or not," observed American author and editor

Irving Dilliard, "Jehovah's Witnesses have done more to help preserve

our freedoms than any other religious group."

Professor C. S. Braden wrote: "They have performed a signal

service to democracy by their fight to preserve their civil rights, for

in their struggle they have done much to secure those rights for every

minority group in America."

"The cases that the Witnesses were involved in formed the bedrock

of 1st Amendment protections for all citizens," said Paul Polidoro, a

lawyer who argued the Watchtower Society's case before the Supreme Court

in February 2002. "These cases were a good vehicle for the courts to

address the protections that were to be accorded free speech, the free

press and free exercise of religion. In addition, the cases marked the

emergence of individual rights as an issue within the U.S. court system.

Before the Jehovah's Witnesses brought several dozen cases before the U.S. Supreme Court during the 1930s and 1940s, the Court had handled few cases contesting laws that restricted freedom of speech and freedom of religion. Until then, the First Amendment had only been applied to Congress and the federal government.

However, the cases brought before the Court by the Jehovah's

Witnesses allowed the Court to consider a range of issues: mandatory

flag salute, sedition, free speech, literature distribution and military

draft law. These cases proved to be pivotal moments in the formation of

constitutional law.

Jehovah's Witnesses' court victories have strengthened rights

including the protection of religious conduct from federal and state

interference, the right to abstain from patriotic rituals and military

service and the right to engage in public discourse.

During the World War II era, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in

favor of Jehovah's Witnesses in several landmark cases that helped pave

the way for the modern civil rights movement. In all, Jehovah's

Witnesses brought 23 separate First Amendment actions before the U.S.

Supreme Court between 1938 and 1946.

Lemon test

The Supreme Court has consistently held fast to the rule of strict separation of church and state when matters of prayer are involved.

In Engel v. Vitale (1962) the Court ruled that government-imposed nondenominational prayer in public school was unconstitutional. In Lee v. Weisman

(1992), the Court ruled prayer established by a school principal at a

middle school graduation was also unconstitutional, and in Santa Fe Independent School Dist. v. Doe

(2000) it ruled that school officials may not directly impose

student-led prayer during high school football games nor establish an

official student election process for the purpose of indirectly

establishing such prayer. The distinction between force of government

and individual liberty is the cornerstone of such cases. Each case

restricts acts by government designed to establish prayer while

explicitly or implicitly affirming students' individual freedom to pray.

The Court has therefore tried to determine a way to deal with church/state questions. In Lemon v. Kurtzman

(1971), the Court created a three-part test for laws dealing with

religious establishment. This determined that a law was constitutional

if it:

- Had a secular purpose

- Neither advanced nor inhibited religion

- Did not foster an excessive government entanglement with religion.

Some examples of where inhibiting religion has been struck down:

- In Widmar v. Vincent, 454 U.S. 263 (1981), the Court ruled that a Missouri law prohibiting religious groups from using state university grounds and buildings for religious worship was unconstitutional. As a result, Congress decided in 1984 that this should apply to secondary and primary schools as well, passing the Equal Access Act, which prevents public schools from discriminating against students based on "religious, political, philosophical or other content of the speech at such meetings". In Board of Education of Westside Community Schools v. Mergens, 496 U.S. 226, 236 (1990), the Court upheld this law when it ruled that a school board's refusal to allow a Christian Bible club to meet in a public high school classroom violated the act.

- In Good News Club v. Milford Central School, 533 U.S. 98 (2001), the Court ruled that religious groups must be allowed to use public schools after hours if the same access is granted to other community groups.

- In Rosenberger v. Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995), the Supreme Court found that the University of Virginia was unconstitutionally withholding funds from a religious student magazine.

State constitutions and laws

Under the doctrine of Incorporation,

the first amendment has been made applicable to the states. Therefore,

the states must guarantee the freedom of religion in the same way the

federal government must.

Many states have freedom of religion established in their

constitution, though the exact legal consequences of this right vary for

historical and cultural reasons. Most states interpret "freedom of

religion" as including the freedom of long-established religious communities to remain intact and not be destroyed. By extension, democracies interpret "freedom of religion" as the right of each individual to freely choose to convert from one religion to another, mix religions, or abandon religion altogether.

Public offices and the military

Religious tests

The affirmation or denial of specific religious beliefs had, in the

past, been made into qualifications for public office; however, the United States Constitution

states that the inauguration of a President may include an

"affirmation" of the faithful execution of his duties rather than an

"oath" to that effect — this provision was included in order to respect

the religious prerogatives of the Quakers, a Protestant Christian denomination that declines the swearing of oaths.

The U.S. Constitution also provides that "No religious Test shall ever

be required as a Qualification of any Office or public Trust under the

United States."

Several states have language included in their constitutions that

requires state office-holders to have particular religious beliefs. These include Arkansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas.

Some of these beliefs (or oaths) were historically required of jurors

and witnesses in court. Even though they are still on the books, these

provisions have been rendered unenforceable by U.S. Supreme Court decisions.

With reference to the use of animals, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the cases of the Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah

in 1993 upheld the right of Santeria adherents to practice ritual

animal sacrifice with Justice Anthony Kennedy stating in the decision,

"religious beliefs need not be acceptable, logical, consistent or

comprehensible to others in order to merit First Amendment protection".

(quoted by Justice Kennedy from the opinion by Justice Burger in Thomas v. Review Board of the Indiana Employment Security Division 450 U.S. 707 (1981)) Likewise in Texas in 2009, issues that related to animal sacrifice and animal rights were taken to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in the case of Jose Merced, President Templo Yoruba Omo Orisha Texas, Inc., v. City of Euless.

The court ruled that the free exercise of religion was meritorious and

prevailing and that Merced was entitled under the Texas Religious

Freedom and Restoration Act (TRFRA) to an injunction preventing the city

of Euless, Texas from enforcing its ordinances that burdened his religious practices relating to the use of animals.

Religious liberty has not prohibited states or the federal government from prohibiting or regulating certain behaviors; i.e. prostitution, gambling, alcohol and certain drugs, although some libertarians interpret religious freedom to extend to these behaviors. The United States Supreme Court has ruled that a right to privacy or a due process right does prevent the government from prohibiting adult access to birth control, pornography, and from outlawing sodomy between consenting adults and early trimester abortions.

In practice committees questioning nominees for public office

sometimes ask detailed questions about their religious beliefs. The

political reason for this may be to expose the nominee to public

ridicule for holding a religious belief contrary to the majority of the

population. This practice has drawn ire from some for violating the No

Religious Test Clause.

States

Some

state constitutions in the US require belief in God or a Supreme Being

as a prerequisite for holding public office or being a witness in court.

This applies to Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi,[45] North Carolina, where the requirement was challenged and overturned in Voswinkel v. Hunt (1979), South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, debatably.

A unanimous 1961 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Torcaso v. Watkins held that the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the federal Constitution override these state requirements, so they are not enforced.

Oath of public office

The no religious test clause

of the U.S. constitution states that "no religious test shall ever be

required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the

United States." Although it has become tradition for US presidents to

end their Presidential Oath with "so help me God", this is not required by the Constitution. The same applies to the Vice President, the House of Representatives, the Senate, the members of the Cabinet, and all other civil and military officers and federal employees, who can either make an affirmation or take an oath ending with "so help me God."

Military

After reports in August 2010 that soldiers who refused to attend a

Christian band's concert at a Virginia military base were essentially

punished by being banished to their barracks and told to clean them up,

an Army spokesman said that an investigation was underway and "If

something like that were to have happened, it would be contrary to Army

policy."

Religious holidays and work

Problems sometimes arise in the workplace concerning religious

observance when a private employer discharges an employee for failure to

report to work on what the employee considers a holy day

or a day of rest. In the United States, the view that has generally

prevailed is that firing for any cause in general renders a former

employee ineligible for unemployment compensation, but that this is no

longer the case if the 'cause' is religious in nature, especially an

employee's unwillingness to work during Jewish Shabbat, Christian Sabbath, Hindu Diwali, or Muslim jumu'ah.

Situation of minority groups

Catholics

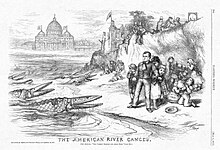

Famous 1876 editorial cartoon by Thomas Nast showing bishops as crocodiles attacking public schools, with the connivance of Irish Catholic politicians

John Higham described anti-Catholicism as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history". Anti-Catholicism which was prominent in the United Kingdom was exported to the United States.

Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The

first, derived from the heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the 16th century,

consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and

dominated Anti-Catholic thought until the late 17th century. The second

was a more secular variety which focused on the supposed intrigue of the

Catholics intent on extending medieval despotism worldwide.

Historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. has called Anti-Catholicism "the deepest-held bias in the history of the American people."

Rev. Branford Clarke illustration in Heroes of the Fiery Cross 1928 by Bishop Alma White Published by the Pillar of Fire Church in Zarephath, NJ

During the Plundering Time,

Protestant pirates robbed Catholic residents of the British colony of

Maryland. Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists,

were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of

early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme

anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis

wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in

1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia."

Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against

Roman Catholics. Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Roman

Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

Some of America's Founding Fathers held anti-clerical beliefs. For example, in 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil." Thomas Jefferson wrote: "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government," and, "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."

Some states devised loyalty oaths designed to exclude Catholics from state and local office. The public support for American independence and the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution by prominent American Catholics like Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his second cousins, Bishop John Carroll and Daniel Carroll, allowed Roman Catholics to be included in the constitutional protections of civil and religious liberty.

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the

19th century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx

of Catholic immigrants. Some American Protestants, having an increased

interest in prophecies regarding the end of time, claimed that the

Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation.

The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the

1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob

violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of

Catholics.

This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the

culture of the United States. The nativist movement found expression in a

national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856.

The founder of the Know-Nothing movement, Lewis C. Levin,

based his political career entirely on anti-Catholicism, and served

three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1845–1851), after

which he campaigned for Fillmore and other "nativist" candidates.

After 1875 many states passed constitutional provisions, called "Blaine Amendments, forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools. In 2002, the United States Supreme Court

partially vitiated these amendments, when they ruled that vouchers were

constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school, even if it

were religious.

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in the 1920s; anti-Catholics,

including the Ku Klux Klan, believed that Catholicism was incompatible

with democracy and that parochial schools encouraged separatism and kept

Catholics from becoming loyal Americans. The Catholics responded to

such prejudices by repeatedly asserting their rights as American

citizens and by arguing that they, not the nativists (anti-Catholics),

were true patriots since they believed in the right to freedom of

religion.

The 1928 presidential campaign of Al Smith was a rallying point for the Klan and the tide of anti-Catholicism in the U.S. The Catholic Church of the Little Flower was first built in 1925 in Royal Oak, Michigan, a largely Protestant area. Two weeks after it opened, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of the church. The church burned down in a fire in 1936. In response, the church built a fireproof crucifixion tower, as a "cross they could not burn".

In 1922, the voters of Oregon passed an initiative amending Oregon Law

Section 5259, the Compulsory Education Act. The law unofficially

became known as the Oregon School Law. The citizens' initiative was

primarily aimed at eliminating parochial schools, including Catholic schools.

The law caused outraged Catholics to organize locally and nationally

for the right to send their children to Catholic schools. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters

(1925), the United States Supreme Court declared the Oregon's

Compulsory Education Act unconstitutional in a ruling that has been

called "the Magna Carta of the parochial school system." However, there

is still controversy over the legality of parish schools. In December

2018, Ed Mechmann, the director of public policy at the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York noted that the new regulations from the New York State Education Department

would "give local school boards virtually unlimited power over private

religious schools. There is no protection against government officials

who are hostile to religious schools or who just want to eliminate the

competition."

In 1928, Al Smith became the first Roman Catholic to gain a major party's nomination for president, and his religion became an issue during the campaign. Many Protestants feared that Smith would take orders from church leaders in Rome in making decisions affecting the country.

A key factor that hurt John F. Kennedy in his 1960 campaign for the presidency of the United States was the widespread prejudice against his Roman Catholic religion; some Protestants, including Norman Vincent Peale, believed that, if he were elected president, Kennedy would have to take orders from the pope in Rome. To address fears that his Roman Catholicism would impact his decision-making, John F. Kennedy

famously told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September

12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the

Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a

Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters — and the

Church does not speak for me."

He promised to respect the separation of church and state and not to

allow Catholic officials to dictate public policy to him. Kennedy also

raised the question of whether one-quarter of Americans were relegated

to second-class citizenship just because they were Catholic.

Kennedy went on to win the national popular vote over Richard Nixon by just one tenth of one percentage point (0.1%) – the closest popular-vote margin of the 20th century. In the electoral college, Kennedy's victory was larger, as he took 303 electoral votes to Nixon's 219 (269 were needed to win). The New York Times,

summarizing the discussion late in November, spoke of a "narrow

consensus" among the experts that Kennedy had won more than he lost as a

result of his Catholicism, as Catholics flocked to Kennedy to demonstrate their group solidarity in demanding political equality.

In 2011, The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops argued that the Obama Administration put an undue burden upon Catholics and forced them to violate their right to freedom of religion as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Another concern relating to the Catholic Church and politics in the United States

is the freedom to provide church services to illegally undocumented

immigrants as most hail from predominantly Roman Catholic nations.

Holy See–United States relations resumed in 1984.

Christian Scientists

The Christian Scientists have specific protections relating to their beliefs on refusing medical care and the use of prayer.

Latter Day Saint movement 1820–90

Historically, the Latter Day Saint movement, which is often called Mormonism, has been the victim of religious violence beginning with reports by founder Joseph Smith immediately after his First Vision 1820 and continuing as the movement grew and migrated from its inception in western New York to Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. The violence culminated when Smith was assassinated by a mob of 200 men in Carthage Jail

in 1844. Joseph Smith had surrendered himself previously to the

authorities, who failed to protect him. As a result of the violence they

were faced with in the East, the Mormon pioneers, led by Brigham Young, migrated westwards and eventually founded Salt Lake City, and many other communities along the Mormon Corridor.

Smith and his followers experienced relatively low levels of persecution in New York and Ohio, although one incident involved church members being tarred and feathered.

They would eventually move on to Missouri, where some of the worst

atrocities against Mormons would take place. Smith declared the area

around Independence, Missouri to be the site of Zion,

inspiring a massive influx of Mormon converts. Locals, alarmed by

rumors of the strange, new religion (including rumors of polygamy),[citation needed] attempted to drive the Mormons out. This resulted in the 1838 Mormon War, the Haun's Mill massacre, and the issue of the Missouri Executive Order 44 by Governor Lilburn Boggs, which ordered " ... Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state ... ".

The majority of Mormons would flee to Illinois, where they were

received warmly by the village of Commerce, Illinois. The Mormons

quickly expanded the town and renamed it Nauvoo, which was one of the largest cities in Illinois at the time.

The economic, political, and religious dominance of the Mormons (Smith

was mayor of the city and commander of the local militia, the Nauvoo Legion) inspired mobs to attack the city, and Smith was arrested for ordering the destruction of an anti-Mormon newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor, although he acted with the consent of the city council. He was imprisoned, along with his brother Hyrum Smith, at Carthage Jail, where they were attacked by a mob and murdered.

After a succession crisis, most of the Mormons united under Brigham Young,

who organized an evacuation from Nauvoo and from the United States

itself after the federal government refused to protect the Mormons. Young and an eventual 50,000–70,000 would cross the Great Plains to settle in the Salt Lake Valley and the surrounding area. After the events of the Mexican–American War, the area became a United States territory. Young immediately petitioned for the addition of the State of Deseret, but the federal government declined. Instead, Congress carved out the much smaller Utah Territory.

Over the next 46 years, several actions of the federal government were

directed at Mormons, specifically to curtail the practice of polygamy

and to reduce their political and economic power. These included the Utah War, Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, Poland Act, Edmunds Act, and Edmunds–Tucker Act. In 1890, LDS Church president Wilford Woodruff issued the Manifesto, ending polygamy.

With the concept of plural marriage, from 1830 to 1890 the Mormon faith allowed its members to practice polygamy; after 1843 this was limited to polygyny

(one man could have several wives). The notion of polygamy was not only

generally disdained by most of Joseph Smith's contemporaries, it is also contrary to the traditional Christian understanding of marriage. After 1844 the United States government passed legislation aimed specifically at the Mormon practice of polygamy until The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) officially renounced it. In the case of Reynolds v. United States,

the U.S. supreme court concluded that "religious duty" was not a

suitable defense to an indictment for polygamy; therefore, a law against

polygamy is not legally considered to discriminate against a religion

that endorses polygamy. When their appeals to the courts and lawmakers

were exhausted and once church leaders were satisfied that God had

accepted what they saw as their sacrifice for the principle, the prophet

leader of the church announced that he had received inspiration that

God had accepted their obedience and rescinded the commandment for

plural marriage. In 1890, an official declaration was issued by the church prohibiting further plural marriages. Utah was admitted to the Union on January 4, 1896.

Native Americans

Aside from the general issues in the relations between Europeans and Native Americans since the initial European colonization of the Americas, there has been a historic suppression of Native American religions as well as some current charges of religious discrimination against Native Americans by the U.S. government.

With the practice of the Americanization of Native Americans, Native American children were sent to Christian boarding schools where they were forced to worship as Christians and traditional customs were banned.

Until the Freedom of Religion Act 1978, "spiritual leaders [of Native

Americans] ran the risk of jail sentences of up to 30 years for simply

practicing their rituals." The traditional indigenous Sun Dance was illegal from the 1880s (Canada) or 1904 (USA) to the 1980s.

Continuing charges of religious discrimination have largely centered on the eagle feather law, the use of ceremonial peyote, and the repatriation of Native American human remains and cultural and religious objects:

- The eagle feather law, which governs the possession and religious use of eagle feathers, was written with the intention to protect then dwindling eagle populations on one hand while still protecting traditional Native American spiritual and religious customs, to which the use of eagle feather is central, on the other hand. As a result, the possession of eagle feathers is restricted to ethnic Native Americans, a policy that is seen as controversial for several reasons.

- Peyote, a spineless cactus found in the desert southwest and Mexico, is commonly used in certain traditions of Native American religion and spirituality, most notably in the Native American Church. Prior to the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) in 1978, and as amended in 1994, the religious use of peyote was not afforded legal protection. This resulted in the arrest of many Native Americans and non-Native Americans participating in traditional indigenous religion and spirituality.

- Native Americans often hold strong personal and spiritual connections to their ancestors and often believe that their remains should rest undisturbed. This has often placed Native Americans at odds with archaeologists who have often dug on Native American burial grounds and other sites considered sacred, often removing artifacts and human remains – an act considered sacrilegious by many Native Americans. For years, Native American communities decried the removal of ancestral human remains and cultural and religious objects, charging that such activities are acts of genocide, religious persecution, and discrimination. Many Native Americans called on the government, museums, and private collectors for the return of remains and sensitive objects for reburial. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which gained passage in 1990, established a means for Native Americans to request the return or "repatriation" of human remains and other sensitive cultural, religious, and funerary items held by federal agencies and federally assisted museums and institutions.

Atheists

A 2006 study at the University of Minnesota showed atheists to be the most distrusted minority among Americans. In the study, sociologists

Penny Edgell, Joseph Gerties and Douglas Hartmann conducted a survey of

American public opinion on attitudes towards different groups. 40% of

respondents characterized atheists as a group that "does not at all

agree with my vision of American society", putting atheists well ahead

of every other group, with the next highest being Muslims (26%) and homosexuals

(23%). When participants were asked whether they agreed with the

statement, "I would disapprove if my child wanted to marry a member of

this group," atheists again led minorities, with 48% disapproval,

followed by Muslims (34%) and African-Americans (27%).

Joe Foley, co-chairman for Campus Atheists and Secular Humanists,

commented on the results, "I know atheists aren't studied that much as a

sociological group, but I guess atheists are one of the last groups

remaining that it's still socially acceptable to hate." A University of British Columbia study conducted in the United States found that believers distrust atheists as much as they distrust rapists. The study also showed that atheists have lower employment prospects.

Several private organizations, the most notable being the Boy Scouts of America, do not allow atheist members.

However, this policy has come under fire by organizations who assert

that the Boy Scouts of America do benefit from taxpayer money and thus

cannot be called a truly private organization, and thus must admit

atheists, and others currently barred from membership. An organization

called Scouting for All, founded by Eagle Scout Steven Cozza, is at the forefront of the movement.

Court cases

In the 1994 case Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet, Supreme Court Justice David Souter wrote in the opinion for the Court that: "government should not prefer one religion to another, or religion to irreligion". Everson v. Board of Education

established that "neither a state nor the Federal Government can pass

laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion

over another". This applies the Establishment Clause to the states as well as the federal government. However, several state constitutions make the protection of persons from religious discrimination conditional on their acknowledgment of the existence of a deity, making freedom of religion in those states inapplicable to atheists. These state constitutional clauses have not been tested. Civil rights cases are typically brought in federal courts, so such state provisions are mainly of symbolic importance.

In Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow (2004), after atheist Michael Newdow challenged the phrase "under God" in the United States Pledge of Allegiance, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

found the phrase unconstitutional. Although the decision was stayed

pending the outcome of an appeal, there was the prospect that the pledge

would cease to be legally usable without modification in schools in the

western United States, over which the Ninth Circuit has jurisdiction. This resulted in political furor, and both houses of Congress passed resolutions condemning the decision, unanimously. On June 26, a Republican-dominated

group of 100–150 congressmen stood outside the capital and recited the

pledge, showing how much they disagreed with the decision. The Supreme Court subsequently reversed the decision, ruling that Newdow did not have standing to bring his case, thus disposing of the case without ruling on the constitutionality of the pledge.

Case studies

- The Eagle Feather Law, which governs the possession and religious use of eagle feathers, was officially written to protect then dwindling eagle populations while still protecting traditional Native American spiritual and religious customs, of which the use of eagles are central. The Eagle Feather Law later met charges of promoting racial and religious discrimination due to the law's provision authorizing the possession of eagle feathers to members of only one ethnic group, Native Americans, and forbidding Native Americans from including non-Native Americans in indigenous customs involving eagle feathers—a common modern practice dating back to the early 16th century.

- Charges of religious and racial discrimination have also been found in the education system. In a recent example, the dormitory policies at Boston University and The University of South Dakota were charged with racial and religious discrimination when they forbade a university dormitory resident from smudging while praying. The policy at The University of South Dakota was later changed to permit students to pray while living in the university dorms.

- In 2004, a case involving five Ohio prison inmates (two followers of Asatru (a modern form of Norse paganism), a minister of the Church of Jesus Christ Christian, a Wiccan witch (neopaganism)), and a Satanist protesting denial of access to ceremonial items and opportunities for group worship was brought before the Supreme Court. The Boston Globe reports on the 2005 decision of Cutter v. Wilkinson in favour of the claimants as a notable case. Among the denied objects was instructions for runic writing requested by an Asatruar. Inmates of the "Intensive Management Unit" at Washington State Penitentiary who are adherents of Asatru in 2001 were deprived of their Thor's Hammer medallions. In 2007, a federal judge confirmed that Asatru adherents in US prisons have the right to possess a Thor's Hammer pendant. An inmate sued the Virginia Department of Corrections after he was denied it while members of other religions were allowed their medallions.

Replacement of freedom of religion with freedom of worship

In

2016, John Miller of the Wall Street Journal noted that the term

'"freedom of religion" was recently restored to US immigrant

naturalization tests and study booklets. It had previously been changed

to the more limited "freedom of worship."