John von Neumann was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, and polymath. Von Neumann was generally regarded as the foremost mathematician of his time and said to be "the last representative of the great mathematicians"; a genius who was comfortable integrating both pure and applied sciences.

He made major contributions to a number of fields, including mathematics (foundations of mathematics, functional analysis, ergodic theory, representation theory, operator algebras, geometry, topology, and numerical analysis), physics (quantum mechanics, hydrodynamics, and quantum statistical mechanics), economics (game theory), computing (Von Neumann architecture, linear programming, self-replicating machines, stochastic computing), and statistics.

He was a pioneer of the application of operator theory to quantum mechanics in the development of functional analysis, and a key figure in the development of game theory and the concepts of cellular automata, the universal constructor and the digital computer.

He published over 150 papers in his life: about 60 in pure mathematics, 60 in applied mathematics, 20 in physics, and the remainder on special mathematical subjects or non-mathematical ones. His last work, an unfinished manuscript written while in hospital, was later published in book form as The Computer and the Brain.

His analysis of the structure of self-replication preceded the discovery of the structure of DNA. In a short list of facts about his life he submitted to the National Academy of Sciences, he stated, "The part of my work I consider most essential is that on quantum mechanics, which developed in Göttingen in 1926, and subsequently in Berlin in 1927–1929. Also, my work on various forms of operator theory, Berlin 1930 and Princeton 1935–1939; on the ergodic theorem, Princeton, 1931–1932."

During World War II, von Neumann worked on the Manhattan Project with theoretical physicist Edward Teller, mathematician Stanisław Ulam and others, problem solving key steps in the nuclear physics involved in thermonuclear reactions and the hydrogen bomb. He developed the mathematical models behind the explosive lenses used in the implosion-type nuclear weapon, and coined the term "kiloton" (of TNT), as a measure of the explosive force generated.

After the war, he served on the General Advisory Committee of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, and consulted for a number of organizations, including the United States Air Force, the Army's Ballistic Research Laboratory, the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. As a Hungarian émigré, concerned that the Soviets would achieve nuclear superiority, he designed and promoted the policy of mutually assured destruction to limit the arms race.

Early life and education

Family background

Von Neumann's birthplace, at 16 Báthory Street, Budapest. Since 1968, it has housed the John von Neumann Computer Society.

Von Neumann was born Neumann János Lajos to a wealthy, acculturated and non-observant Jewish

family (in Hungarian the family name comes first. His given names

equate to John Louis in English). After his arrival in the U.S. he had

been baptized a Roman Catholic prior to the marriage to his Catholic first wife.

Von Neumann was born in Budapest, Kingdom of Hungary, which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

He was the eldest of three brothers; his two younger siblings were

Mihály (English: Michael von Neumann; 1907–1989) and Miklós (Nicholas

Vonneumann, 1911–2011). His father, Neumann Miksa (Max von Neumann, 1873–1928) was a banker, who held a doctorate in law. He had moved to Budapest from Pécs at the end of the 1880s. Miksa's father and grandfather were both born in Ond (now part of the town of Szerencs), Zemplén County, northern Hungary. John's mother was Kann Margit (English: Margaret Kann); her parents were Jakab Kann and Katalin Meisels.

Three generations of the Kann family lived in spacious apartments above

the Kann-Heller offices in Budapest; von Neumann's family occupied an

18-room apartment on the top floor.

On February 20, 1913, Emperor Franz Joseph

elevated his father to the Hungarian nobility for his service to the

Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Neumann family thus acquired the hereditary

appellation Margittai, meaning of Margitta (today Marghita, Romania).

The family had no connection with the town; the appellation was chosen

in reference to Margaret, as was that chosen coat of arms depicting

three marguerites.

Neumann János became margittai Neumann János (John Neumann de

Margitta), which he later changed to the German Johann von Neumann.

Child prodigy

Von Neumann was a child prodigy. When he was 6 years old, he could divide two 8-digit numbers in his head and could converse in Ancient Greek. When the 6-year-old von Neumann caught his mother staring aimlessly, he asked her, "What are you calculating?"

Children did not begin formal schooling in Hungary until they

were ten years of age; governesses taught von Neumann, his brothers and

his cousins. Max believed that knowledge of languages in addition to

Hungarian was essential, so the children were tutored in English,

French, German and Italian. By the age of 8, von Neumann was familiar with differential and integral calculus, but he was particularly interested in history. He read his way through Wilhelm Oncken's 46-volume Allgemeine Geschichte in Einzeldarstellungen.

A copy was contained in a private library Max purchased. One of the

rooms in the apartment was converted into a library and reading room,

with bookshelves from ceiling to floor.

Von Neumann entered the Lutheran Fasori Evangélikus Gimnázium in 1911. Eugene Wigner was a year ahead of von Neumann at the Lutheran School and soon became his friend.

This was one of the best schools in Budapest and was part of a

brilliant education system designed for the elite. Under the Hungarian

system, children received all their education at the one gymnasium. The Hungarian school system produced a generation noted for intellectual achievement, which included Theodore von Kármán (b. 1881), George de Hevesy (b. 1885), Michael Polanyi (b. 1891), Leó Szilárd (b. 1898), Dennis Gabor (b. 1900), Wigner (b. 1902), Edward Teller (b. 1908), and Paul Erdős (b. 1913). Collectively, they were sometimes known as "The Martians".

| First few von Neumann ordinals | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 |

|

= Ø |

| 1 | = { 0 } | = {Ø} |

| 2 | = { 0, 1 } | = { Ø, {Ø} } |

| 3 | = { 0, 1, 2 } | = { Ø, {Ø}, {Ø, {Ø}} } |

| 4 | = { 0, 1, 2, 3 } | = { Ø, {Ø}, {Ø, {Ø}}, {Ø, {Ø}, {Ø, {Ø}}} } |

Although Max insisted von Neumann attend school at the grade level

appropriate to his age, he agreed to hire private tutors to give him

advanced instruction in those areas in which he had displayed an aptitude. At the age of 15, he began to study advanced calculus under the renowned analyst Gábor Szegő. On their first meeting, Szegő was so astounded with the boy's mathematical talent that he was brought to tears.

Some of von Neumann's instant solutions to the problems that Szegő

posed in calculus are sketched out on his father's stationery and are

still on display at the von Neumann archive in Budapest. By the age of 19, von Neumann had published two major mathematical papers, the second of which gave the modern definition of ordinal numbers, which superseded Georg Cantor's definition.

At the conclusion of his education at the gymnasium, von Neumann sat

for and won the Eötvös Prize, a national prize for mathematics.

University studies

According to his friend Theodore von Kármán,

von Neumann's father wanted John to follow him into industry and

thereby invest his time in a more financially useful endeavor than

mathematics. In fact, his father requested Theodore von Kármán to

persuade his son not to take mathematics as his major. Von Neumann and his father decided that the best career path was to become a chemical engineer.

This was not something that von Neumann had much knowledge of, so it

was arranged for him to take a two-year, non-degree course in chemistry

at the University of Berlin, after which he sat for the entrance exam to the prestigious ETH Zurich, which he passed in September 1923. At the same time, von Neumann also entered Pázmány Péter University in Budapest, as a Ph.D. candidate in mathematics. For his thesis, he chose to produce an axiomatization of Cantor's set theory.

He graduated as a chemical engineer from ETH Zurich in 1926 (although

Wigner says that von Neumann was never very attached to the subject of

chemistry),

and passed his final examinations for his Ph.D. in mathematics

simultaneously with his chemical engineering degree, of which Wigner

wrote, "Evidently a Ph.D. thesis and examination did not constitute an

appreciable effort." He then went to the University of Göttingen on a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to study mathematics under David Hilbert.

Early career and private life

Excerpt from the university calendars for 1928 and 1928/29 of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin

announcing Neumann's lectures on axiomatic set theory and mathematical

logic, new work in quantum mechanics and special functions of

mathematical physics.

Von Neumann's habilitation was completed on December 13, 1927, and he started his lectures as a Privatdozent at the University of Berlin in 1928, being the youngest person ever elected Privatdozent in the university's history in any subject.

By the end of 1927, von Neumann had published twelve major papers in

mathematics, and by the end of 1929, thirty-two papers, at a rate of

nearly one major paper per month.

His reputed powers of memorization and recall allowed him to quickly

memorize the pages of telephone directories, and recite the names,

addresses and numbers therein. In 1929, he briefly became a Privatdozent at the University of Hamburg, where the prospects of becoming a tenured professor were better, but in October of that year a better offer presented itself when he was invited to Princeton University in Princeton, New Jersey.

On New Year's Day in 1930, von Neumann married Marietta Kövesi, who had studied economics at Budapest University. Von Neumann and Marietta had one child, a daughter, Marina, born in 1935. As of 2017, she is a distinguished professor of business administration and public policy at the University of Michigan. The couple divorced in 1937. In October 1938, von Neumann married Klara Dan, whom he had met during his last trips back to Budapest prior to the outbreak of World War II.

Prior to his marriage to Marietta, von Neumann was baptized a Catholic in 1930.

Von Neumann's father, Max, had died in 1929. None of the family had

converted to Christianity while Max was alive, but all did afterward.

In 1933, he was offered a lifetime professorship on the faculty of the Institute for Advanced Study in New Jersey when that institution's plan to appoint Hermann Weyl fell through.

He remained a mathematics professor there until his death, although he

had announced his intention to resign and become a professor at large at

the University of California. His mother, brothers and in-laws followed von Neumann to the United States in 1939. Von Neumann anglicized

his first name to John, keeping the German-aristocratic surname of von

Neumann. His brothers changed theirs to "Neumann" and "Vonneumann". Von Neumann became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1937, and immediately tried to become a lieutenant in the United States Army's Officers Reserve Corps. He passed the exams easily, but was ultimately rejected because of his age. His prewar analysis of how France would stand up to Germany is often quoted: "Oh, France won't matter."

Klara and John von Neumann were socially active within the local academic community. His white clapboard house at 26 Westcott Road was one of the largest private residences in Princeton.

He took great care of his clothing and would always wear formal suits.

He once wore a three-piece pinstripe when he rode down the Grand Canyon astride a mule.

Hilbert is reported to have asked "Pray, who is the candidate's

tailor?" at von Neumann's 1926 doctoral exam, as he had never seen such

beautiful evening clothes.

Von Neumann held a lifelong passion for ancient history, being renowned for his prodigious historical knowledge. A professor of Byzantine history at Princeton once said that von Neumann had greater expertise in Byzantine history than he did.

Von Neumann liked to eat and drink; his wife, Klara, said that he could count everything except calories. He enjoyed Yiddish and "off-color" humor (especially limericks). He was a non-smoker. In Princeton, he received complaints for regularly playing extremely loud German march music on his gramophone, which distracted those in neighboring offices, including Albert Einstein, from their work.

Von Neumann did some of his best work in noisy, chaotic environments,

and once admonished his wife for preparing a quiet study for him to work

in. He never used it, preferring the couple's living room with its

television playing loudly.

Despite being a notoriously bad driver, he nonetheless enjoyed

driving—frequently while reading a book—occasioning numerous arrests as

well as accidents. When Cuthbert Hurd hired him as a consultant to IBM, Hurd often quietly paid the fines for his traffic tickets.

Von Neumann's closest friend in the United States was mathematician Stanisław Ulam. A later friend of Ulam's, Gian-Carlo Rota,

wrote, "They would spend hours on end gossiping and giggling, swapping

Jewish jokes, and drifting in and out of mathematical talk." When von

Neumann was dying in the hospital, every time Ulam visited, he came

prepared with a new collection of jokes to cheer him up.

He believed that much of his mathematical thought occurred intuitively,

and he would often go to sleep with a problem unsolved and know the

answer immediately upon waking up. Ulam noted that von Neumann's way of thinking might not be visual, but more aural.

Mathematics

Set theory

History of approaches that led to NBG set theory

The axiomatization of mathematics, on the model of Euclid's Elements, had reached new levels of rigour and breadth at the end of the 19th century, particularly in arithmetic, thanks to the axiom schema of Richard Dedekind and Charles Sanders Peirce, and in geometry, thanks to Hilbert's axioms. But at the beginning of the 20th century, efforts to base mathematics on naive set theory suffered a setback due to Russell's paradox (on the set of all sets that do not belong to themselves). The problem of an adequate axiomatization of set theory was resolved implicitly about twenty years later by Ernst Zermelo and Abraham Fraenkel. Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory

provided a series of principles that allowed for the construction of

the sets used in the everyday practice of mathematics, but they did not

explicitly exclude the possibility of the existence of a set that

belongs to itself. In his doctoral thesis of 1925, von Neumann

demonstrated two techniques to exclude such sets—the axiom of foundation and the notion of class.

The axiom of foundation proposed that every set can be

constructed from the bottom up in an ordered succession of steps by way

of the principles of Zermelo and Fraenkel. If one set belongs to another

then the first must necessarily come before the second in the

succession. This excludes the possibility of a set belonging to itself.

To demonstrate that the addition of this new axiom to the others did not

produce contradictions, von Neumann introduced a method of

demonstration, called the method of inner models, which later became an essential instrument in set theory.

The second approach to the problem of sets belonging to themselves took as its base the notion of class, and defines a set as a class which belongs to other classes, while a proper class

is defined as a class which does not belong to other classes. Under the

Zermelo–Fraenkel approach, the axioms impede the construction of a set

of all sets which do not belong to themselves. In contrast, under the

von Neumann approach, the class of all sets which do not belong to

themselves can be constructed, but it is a proper class and not a set.

With this contribution of von Neumann, the axiomatic system of

the theory of sets avoided the contradictions of earlier systems, and

became usable as a foundation for mathematics, despite the lack of a

proof of its consistency. The next question was whether it provided

definitive answers to all mathematical questions that could be posed in

it, or whether it might be improved by adding stronger axioms that could

be used to prove a broader class of theorems. A strongly negative

answer to whether it was definitive arrived in September 1930 at the

historic mathematical Congress of Königsberg, in which Kurt Gödel announced his first theorem of incompleteness:

the usual axiomatic systems are incomplete, in the sense that they

cannot prove every truth which is expressible in their language.

Moreover, every consistent extension of these systems would necessarily

remain incomplete.

Less than a month later, von Neumann, who had participated at the

Congress, communicated to Gödel an interesting consequence of his

theorem: that the usual axiomatic systems are unable to demonstrate

their own consistency. However, Gödel had already discovered this consequence, now known as his second incompleteness theorem, and he sent von Neumann a preprint of his article containing both incompleteness theorems. Von Neumann acknowledged Gödel's priority in his next letter. He never thought much of "the American system of claiming personal priority for everything."

Von Neumann Paradox

Building on the work of Felix Hausdorff, in 1924 Stefan Banach and Alfred Tarski proved that given a solid ball in 3‑dimensional space, there exists a decomposition of the ball into a finite number of disjoint subsets,

that can be reassembled together in a different way to yield two

identical copies of the original ball. Banach and Tarski proved that,

using isometric transformations, the result of taking apart and

reassembling a two-dimensional figure would necessarily have the same

area as the original. This would make creating two unit squares out of

one impossible. However, in a 1929 paper,

von Neumann proved that paradoxical decompositions could use a group of

transformations that include as a subgroup a free group with two

generators. The group of area-preserving transformations contains such

subgroups, and this opens the possibility of performing paradoxical

decompositions using these subgroups. The class of groups isolated by

von Neumann in his work on Banach–Tarski decompositions subsequently was

very important for many areas of mathematics, including von Neumann's

own later work in measure theory (see below).

Ergodic theory

In a series of famous papers that were published in 1932, von Neumann made foundational contributions to ergodic theory, a branch of mathematics that involves the states of dynamical systems with an invariant measure. Of the 1932 papers on ergodic theory, Paul Halmos

writes that even "if von Neumann had never done anything else, they

would have been sufficient to guarantee him mathematical immortality". By then von Neumann had already written his famous articles on operator theory, and the application of this work was instrumental in the von Neumann mean ergodic theorem.

Operator theory

Von Neumann introduced the study of rings of operators, through the von Neumann algebras. A von Neumann algebra is a *-algebra of bounded operators on a Hilbert space that is closed in the weak operator topology and contains the identity operator.[69] The von Neumann bicommutant theorem shows that the analytic definition is equivalent to a purely algebraic definition as being equal to the bicommutant. Von Neumann embarked in 1936, with the partial collaboration of F.J. Murray, on the general study of factors

classification of von Neumann algebras. The six major papers in which

he developed that theory between 1936 and 1940 "rank among the

masterpieces of analysis in the twentieth century". The direct integral was later introduced in 1949 by John von Neumann.

Measure theory

In measure theory, the "problem of measure" for an n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn

may be stated as: "does there exist a positive, normalized, invariant,

and additive set function on the class of all subsets of Rn?" The work of Felix Hausdorff and Stefan Banach had implied that the problem of measure has a positive solution if n = 1 or n = 2 and a negative solution (because of the Banach–Tarski paradox) in all other cases. Von Neumann's work argued that the "problem is essentially group-theoretic in character": the existence of a measure could be determined by looking at the properties of the transformation group

of the given space. The positive solution for spaces of dimension at

most two, and the negative solution for higher dimensions, comes from

the fact that the Euclidean group is a solvable group

for dimension at most two, and is not solvable for higher dimensions.

"Thus, according to von Neumann, it is the change of group that makes a

difference, not the change of space."

In a number of von Neumann's papers, the methods of argument he

employed are considered even more significant than the results. In

anticipation of his later study of dimension theory in algebras of

operators, von Neumann used results on equivalence by finite

decomposition, and reformulated the problem of measure in terms of

functions. In his 1936 paper on analytic measure theory, he used the Haar theorem in the solution of Hilbert's fifth problem in the case of compact groups. In 1938, he was awarded the Bôcher Memorial Prize for his work in analysis.

Geometry

Von Neumann founded the field of continuous geometry. It followed his path-breaking work on rings of operators. In mathematics, continuous geometry is a substitute of complex projective geometry, where instead of the dimension of a subspace being in a discrete set 0, 1, ..., n, it can be an element of the unit interval [0,1]. Earlier, Menger

and Birkhoff had axiomatized complex projective geometry in terms of

the properties of its lattice of linear subspaces. Von Neumann,

following his work on rings of operators, weakened those axioms to

describe a broader class of lattices, the continuous geometries.

While the dimensions of the subspaces of projective geometries are a

discrete set (the non-negative integers), the dimensions of the elements

of a continuous geometry can range continuously across the unit

interval [0,1]. Von Neumann was motivated by his discovery of von Neumann algebras

with a dimension function taking a continuous range of dimensions, and

the first example of a continuous geometry other than projective space

was the projections of the hyperfinite type II factor.

Lattice theory

Between 1937 and 1939, von Neumann worked on lattice theory, the theory of partially ordered sets in which every two elements have a greatest lower bound and a least upper bound. Garrett Birkhoff writes: "John von Neumann's brilliant mind blazed over lattice theory like a meteor".

Von Neumann provided an abstract exploration of dimension in completed complemented modular topological lattices (properties that arise in the lattices of subspaces of inner product spaces):

"Dimension is determined, up to a positive linear transformation, by

the following two properties. It is conserved by perspective mappings

("perspectivities") and ordered by inclusion. The deepest part of the

proof concerns the equivalence of perspectivity with "projectivity by

decomposition"—of which a corollary is the transitivity of

perspectivity."

Additionally, "[I]n the general case, von Neumann proved the

following basic representation theorem. Any complemented modular lattice

L having a "basis" of n ≥ 4 pairwise perspective elements, is isomorphic with the lattice ℛ(R) of all principal right-ideals of a suitable regular ring R.

This conclusion is the culmination of 140 pages of brilliant and

incisive algebra involving entirely novel axioms. Anyone wishing to get

an unforgettable impression of the razor edge of von Neumann's mind,

need merely try to pursue this chain of exact reasoning for

himself—realizing that often five pages of it were written down before

breakfast, seated at a living room writing-table in a bathrobe."

Mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics

Von Neumann was the first to establish a rigorous mathematical framework for quantum mechanics, known as the Dirac–von Neumann axioms, with his 1932 work Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics.

After having completed the axiomatization of set theory, he began to

confront the axiomatization of quantum mechanics. He realized, in 1926,

that a state of a quantum system could be represented by a point in a

(complex) Hilbert space that, in general, could be infinite-dimensional

even for a single particle. In this formalism of quantum mechanics,

observable quantities such as position or momentum are represented as linear operators acting on the Hilbert space associated with the quantum system.

The physics of quantum mechanics was thereby reduced to the mathematics of Hilbert spaces and linear operators acting on them. For example, the uncertainty principle,

according to which the determination of the position of a particle

prevents the determination of its momentum and vice versa, is translated

into the non-commutativity of the two corresponding operators.

This new mathematical formulation included as special cases the

formulations of both Heisenberg and Schrödinger. When Heisenberg was informed von Neumann had clarified the difference between an unbounded operator that was a self-adjoint operator and one that was merely symmetric, Heisenberg replied "Eh? What is the difference?"

Von Neumann's abstract treatment permitted him also to confront

the foundational issue of determinism versus non-determinism, and in the

book he presented a proof that the statistical results of quantum

mechanics could not possibly be averages of an underlying set of

determined "hidden variables," as in classical statistical mechanics. In

1935, Grete Hermann published a paper arguing that the proof contained a conceptual error and was therefore invalid. Hermann's work was largely ignored until after John S. Bell made essentially the same argument in 1966. However, in 2010, Jeffrey Bub argued that Bell had misconstrued von Neumann's proof, and pointed out that the proof, though not valid for all hidden variable theories,

does rule out a well-defined and important subset. Bub also suggests

that von Neumann was aware of this limitation, and that von Neumann did

not claim that his proof completely ruled out hidden variable theories. The validity of Bub's argument is, in turn, disputed. In any case, Gleason's Theorem of 1957 fills the gaps in von Neumann's approach.

Von Neumann's proof inaugurated a line of research that ultimately led, through the work of Bell in 1964 on Bell's theorem, and the experiments of Alain Aspect in 1982, to the demonstration that quantum physics either requires a notion of reality substantially different from that of classical physics, or must include nonlocality in apparent violation of special relativity.

In a chapter of The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, von Neumann deeply analyzed the so-called measurement problem. He concluded that the entire physical universe could be made subject to the universal wave function.

Since something "outside the calculation" was needed to collapse the

wave function, von Neumann concluded that the collapse was caused by the

consciousness of the experimenter. Von Neumann argued that the

mathematics of quantum mechanics allows the collapse of the wave

function to be placed at any position in the causal chain from the

measurement device to the "subjective consciousness" of the human

observer. Although this view was accepted by Eugene Wigner, the Von Neumann–Wigner interpretation never gained acceptance amongst the majority of physicists). The Von Neumann–Wigner interpretation has been summarized as follows:

The rules of quantum mechanics are correct but there is only one system which may be treated with quantum mechanics, namely the entire material world. There exist external observers which cannot be treated within quantum mechanics, namely human (and perhaps animal) minds, which perform measurements on the brain causing wave function collapse.

Though theories of quantum mechanics continue to evolve to this day,

there is a basic framework for the mathematical formalism of problems in

quantum mechanics which underlies the majority of approaches and can be

traced back to the mathematical formalisms and techniques first used by

von Neumann. In other words, discussions about interpretation of the theory, and extensions to it, are now mostly conducted on the basis of shared assumptions about the mathematical foundations.

Von Neumann Entropy

Von Neumann entropy is extensively used in different forms (conditional entropies, relative entropies, etc.) in the framework of quantum information theory. Entanglement measures are based upon some quantity directly related to the von Neumann entropy. Given a statistical ensemble of quantum mechanical systems with the density matrix , it is given by Many of the same entropy measures in classical information theory can also be generalized to the quantum case, such as Holevo entropy and the conditional quantum entropy.

Quantum mutual information

Quantum

information theory is largely concerned with the interpretation and

uses of von Neumann entropy. The von Neumann entropy is the cornerstone

in the development of quantum information theory, while the Shannon entropy

applies to classical information theory. This is considered a

historical anomaly, as it might have been expected that Shannon entropy

was discovered prior to Von Neumann entropy, given the latter's more

widespread application to quantum information theory. However, the

historical reverse occurred. Von Neumann first discovered von Neumann

entropy, and applied it to questions of statistical physics. Decades

later, Shannon developed an information-theoretic formula for use in

classical information theory, and asked von Neumann what to call it,

with von Neumman telling him to call it Shannon entropy, as it was a

special case of von Neumann entropy.

Density matrix

The formalism of density operators and matrices was introduced by von Neumann in 1927 and independently, but less systematically by Lev Landau and Felix Bloch

in 1927 and 1946 respectively. The density matrix is an alternative

way in which to represent the state of a quantum system, which could

otherwise be represented using the wavefunction. The density matrix

allows the solution of certain time-dependent problems in quantum mechanics.

Von Neumann measurement scheme

The von Neumann measurement scheme, the ancestor of quantum decoherence

theory, represents measurements projectively by taking into account the

measuring apparatus which is also treated as a quantum object. The

'projective measurement' scheme introduced by von Neumann, led to the

development of quantum decoherence theories.

Quantum logic

Von Neumann first proposed a quantum logic in his 1932 treatise Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, where he noted that projections on a Hilbert space

can be viewed as propositions about physical observables. The field of

quantum logic was subsequently inaugurated, in a famous paper of 1936 by

von Neumann and Garrett Birkhoff, the first work ever to introduce

quantum logics, wherein von Neumann and Birkhoff first proved that quantum mechanics requires a propositional calculus

substantially different from all classical logics and rigorously

isolated a new algebraic structure for quantum logics. The concept of

creating a propositional calculus for quantum logic was first outlined

in a short section in von Neumann's 1932 work, but in 1936, the need for

the new propositional calculus was demonstrated through several proofs.

For example, photons cannot pass through two successive filters that

are polarized perpendicularly (e.g., one horizontally and the other vertically), and therefore, a fortiori,

it cannot pass if a third filter polarized diagonally is added to the

other two, either before or after them in the succession, but if the

third filter is added in between the other two, the photons will, indeed, pass through. This experimental fact is translatable into logic as the non-commutativity of conjunction . It was also demonstrated that the laws of distribution of classical logic, and , are not valid for quantum theory.

The reason for this is that a quantum disjunction, unlike the

case for classical disjunction, can be true even when both of the

disjuncts are false and this is, in turn, attributable to the fact that

it is frequently the case, in quantum mechanics, that a pair of

alternatives are semantically determinate, while each of its members are

necessarily indeterminate. This latter property can be illustrated by a

simple example. Suppose we are dealing with particles (such as

electrons) of semi-integral spin (spin angular momentum) for which there

are only two possible values: positive or negative. Then, a principle

of indetermination establishes that the spin, relative to two different

directions (e.g., x and y) results in a pair of incompatible quantities. Suppose that the state ɸ of a certain electron verifies the proposition "the spin of the electron in the x direction is positive." By the principle of indeterminacy, the value of the spin in the direction y will be completely indeterminate for ɸ. Hence, ɸ can verify neither the proposition "the spin in the direction of y is positive" nor

the proposition "the spin in the direction of y is negative." Nevertheless, the disjunction of the propositions "the spin in the direction of y is positive or the spin in the direction of y is negative" must be true for ɸ.

In the case of distribution, it is therefore possible to have a situation in which , while .

As Hilary Putnam writes, von Neumann replaced classical logic with a logic constructed in orthomodular lattices (isomorphic to the lattice of subspaces of the Hilbert space of a given physical system).

Game theory

Von Neumann founded the field of game theory as a mathematical discipline. Von Neumann proved his minimax theorem in 1928. This theorem establishes that in zero-sum games with perfect information (i.e. in which players know at each time all moves that have taken place so far), there exists a pair of strategies

for both players that allows each to minimize his maximum losses, hence

the name minimax. When examining every possible strategy, a player must

consider all the possible responses of his adversary. The player then

plays out the strategy that will result in the minimization of his

maximum loss.

Such strategies, which minimize the maximum loss for each player,

are called optimal. Von Neumann showed that their minimaxes are equal

(in absolute value) and contrary (in sign). Von Neumann improved and

extended the minimax theorem to include games involving imperfect

information and games with more than two players, publishing this result

in his 1944 Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (written with Oskar Morgenstern).

Morgenstern wrote a paper on game theory and thought he would show it

to von Neumann because of his interest in the subject. He read it and

said to Morgenstern that he should put more in it. This was repeated a

couple of times, and then von Neumann became a coauthor and the paper

became 100 pages long. Then it became a book. The public interest in

this work was such that The New York Times ran a front-page story. In this book, von Neumann declared that economic theory needed to use functional analytic methods, especially convex sets and topological fixed-point theorem, rather than the traditional differential calculus, because the maximum-operator did not preserve differentiable functions.

Independently, Leonid Kantorovich's functional analytic work on mathematical economics also focused attention on optimization theory, non-differentiability, and vector lattices. Von Neumann's functional-analytic techniques—the use of duality pairings of real vector spaces to represent prices and quantities, the use of supporting and separating hyperplanes and convex sets, and fixed-point theory—have been the primary tools of mathematical economics ever since.

Mathematical economics

Von

Neumann raised the intellectual and mathematical level of economics in

several influential publications. For his model of an expanding economy,

von Neumann proved the existence and uniqueness of an equilibrium using

his generalization of the Brouwer fixed-point theorem. Von Neumann's model of an expanding economy considered the matrix pencil A − λB with nonnegative matrices A and B; von Neumann sought probability vectors p and q and a positive number λ that would solve the complementarity equation

along with two inequality systems expressing economic efficiency. In this model, the (transposed) probability vector p

represents the prices of the goods while the probability vector q

represents the "intensity" at which the production process would run.

The unique solution λ represents the growth factor which is 1 plus the rate of growth of the economy; the rate of growth equals the interest rate.

Von Neumann's results have been viewed as a special case of linear programming,

where von Neumann's model uses only nonnegative matrices. The study of

von Neumann's model of an expanding economy continues to interest

mathematical economists with interests in computational economics.

This paper has been called the greatest paper in mathematical economics

by several authors, who recognized its introduction of fixed-point

theorems, linear inequalities, complementary slackness, and saddlepoint duality.

In the proceedings of a conference on von Neumann's growth model, Paul

Samuelson said that many mathematicians had developed methods useful to

economists, but that von Neumann was unique in having made significant

contributions to economic theory itself.

Von Neumann's famous 9-page paper started life as a talk at

Princeton and then became a paper in German, which was eventually

translated into English. His interest in economics that led to that

paper began as follows: When lecturing at Berlin in 1928 and 1929 he

spent his summers back home in Budapest, and so did the economist Nicholas Kaldor, and they hit it off. Kaldor recommended that von Neumann read a book by the mathematical economist Léon Walras.

Von Neumann found some faults in that book and corrected them, for

example, replacing equations by inequalities. He noticed that Walras's General Equilibrium Theory and Walras' Law,

which led to systems of simultaneous linear equations, could produce

the absurd result that the profit could be maximized by producing and

selling a negative quantity of a product. He replaced the equations by

inequalities, introduced dynamic equilibria, among other things, and

eventually produced the paper.

Linear programming

Building

on his results on matrix games and on his model of an expanding

economy, von Neumann invented the theory of duality in linear

programming, after George Dantzig

described his work in a few minutes, when an impatient von Neumann

asked him to get to the point. Then, Dantzig listened dumbfounded while

von Neumann provided an hour lecture on convex sets, fixed-point theory,

and duality, conjecturing the equivalence between matrix games and

linear programming.

Later, von Neumann suggested a new method of linear programming, using the homogeneous linear system of Gordan (1873), which was later popularized by Karmarkar's algorithm. Von Neumann's method used a pivoting algorithm between simplices, with the pivoting decision determined by a nonnegative least squares subproblem with a convexity constraint (projecting the zero-vector onto the convex hull of the active simplex). Von Neumann's algorithm was the first interior point method of linear programming.

Mathematical statistics

Von Neumann made fundamental contributions to mathematical statistics.

In 1941, he derived the exact distribution of the ratio of the mean

square of successive differences to the sample variance for independent

and identically normally distributed variables. This ratio was applied to the residuals from regression models and is commonly known as the Durbin–Watson statistic

for testing the null hypothesis that the errors are serially

independent against the alternative that they follow a stationary first

order autoregression.

Subsequently, Denis Sargan and Alok Bhargava extended the results for testing if the errors on a regression model follow a Gaussian random walk (i.e., possess a unit root) against the alternative that they are a stationary first order autoregression.

Fluid dynamics

Von Neumann made fundamental contributions in the field of fluid dynamics.

Von Neumann's contributions to fluid dynamics included his discovery of the classic flow solution to blast waves, and the co-discovery (independently of Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich and Werner Döring) of the ZND detonation model of explosives. During the 1930s, von Neumann became an authority on the mathematics of shaped charges.

Later with Robert D. Richtmyer, von Neumann developed an algorithm defining artificial viscosity that improved the understanding of shock waves.

When computers solved hydrodynamic or aerodynamic problems, they tried

to put too many computational grid points at regions of sharp

discontinuity (shock waves). The mathematics of artificial viscosity smoothed the shock transition without sacrificing basic physics.

Von Neumann soon applied computer modelling to the field,

developing software for his ballistics research. During WW2, he arrived

one day at the office of R.H. Kent, the Director of the US Army's Ballistic Research Laboratory,

with a computer program he had created for calculating a

one-dimensional model of 100 molecules to simulate a shock wave. Von

Neumann then gave a seminar on his computer program to an audience which

included his friend Theodore von Kármán. After von Neumann had finished, von Kármán said "Well, Johnny, that's very interesting. Of course you realize Lagrange also used digital models to simulate continuum mechanics." It was evident from von Neumann's face, that he had been unaware of Lagrange's Mécanique analytique.

Mastery of mathematics

Stan

Ulam, who knew von Neumann well, described his mastery of mathematics

this way: "Most mathematicians know one method. For example, Norbert Wiener had mastered Fourier transforms.

Some mathematicians have mastered two methods and might really impress

someone who knows only one of them. John von Neumann had mastered three

methods." He went on to explain that the three methods were:

- A facility with the symbolic manipulation of linear operators;

- An intuitive feeling for the logical structure of any new mathematical theory;

- An intuitive feeling for the combinatorial superstructure of new theories.

Edward Teller wrote that "Nobody knows all science, not even von

Neumann did. But as for mathematics, he contributed to every part of it

except number theory and topology. That is, I think, something unique."

Von Neumann was asked to write an essay for the layman describing

what mathematics is, and produced a beautiful analysis. He explained

that mathematics straddles the world between the empirical and logical,

arguing that geometry was originally empirical, but Euclid constructed a

logical, deductive theory. However, he argued, that there is always the

danger of straying too far from the real world and becoming irrelevant

sophistry.

Nuclear weapons

Von Neumann's wartime Los Alamos ID badge photo

Manhattan Project

Beginning in the late 1930s, von Neumann developed an expertise in explosions—phenomena

that are difficult to model mathematically. During this period, von

Neumann was the leading authority of the mathematics of shaped charges. This led him to a large number of military consultancies, primarily for the Navy, which in turn led to his involvement in the Manhattan Project. The involvement included frequent trips by train to the project's secret research facilities at the Los Alamos Laboratory in a remote part of New Mexico.

Von Neumann made his principal contribution to the atomic bomb in the concept and design of the explosive lenses that were needed to compress the plutonium core of the Fat Man weapon that was later dropped on Nagasaki. While von Neumann did not originate the "implosion"

concept, he was one of its most persistent proponents, encouraging its

continued development against the instincts of many of his colleagues,

who felt such a design to be unworkable. He also eventually came up with

the idea of using more powerful shaped charges and less fissionable

material to greatly increase the speed of "assembly".

When it turned out that there would not be enough uranium-235

to make more than one bomb, the implosive lens project was greatly

expanded and von Neumann's idea was implemented. Implosion was the only

method that could be used with the plutonium-239 that was available from the Hanford Site. He established the design of the explosive lenses required, but there remained concerns about "edge effects" and imperfections in the explosives. His calculations showed that implosion would work if it did not depart by more than 5% from spherical symmetry. After a series of failed attempts with models, this was achieved by George Kistiakowsky, and the construction of the Trinity bomb was completed in July 1945.

In a visit to Los Alamos in September 1944, von Neumann showed

that the pressure increase from explosion shock wave reflection from

solid objects was greater than previously believed if the angle of

incidence of the shock wave was between 90° and some limiting angle. As a

result, it was determined that the effectiveness of an atomic bomb

would be enhanced with detonation some kilometers above the target,

rather than at ground level.

Implosion mechanism

Von Neumann, four other scientists, and various military personnel

were included in the target selection committee that was responsible for

choosing the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the first targets of the atomic bomb.

Von Neumann oversaw computations related to the expected size of the

bomb blasts, estimated death tolls, and the distance above the ground at

which the bombs should be detonated for optimum shock wave propagation

and thus maximum effect. The cultural capital Kyoto, which had been spared the bombing inflicted upon militarily significant cities, was von Neumann's first choice, a selection seconded by Manhattan Project leader General Leslie Groves. However, this target was dismissed by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson.

On July 16, 1945, von Neumann and numerous other Manhattan

Project personnel were eyewitnesses to the first test of an atomic bomb

detonation, which was code-named Trinity. The event was conducted as a test of the implosion method device, at the bombing range near Alamogordo Army Airfield, 35 miles (56 km) southeast of Socorro, New Mexico. Based on his observation alone, von Neumann estimated the test had resulted in a blast equivalent to 5 kilotons of TNT (21 TJ) but Enrico Fermi

produced a more accurate estimate of 10 kilotons by dropping scraps of

torn-up paper as the shock wave passed his location and watching how far

they scattered. The actual power of the explosion had been between 20

and 22 kilotons. It was in von Neumann's 1944 papers that the expression "kilotons" appeared for the first time. After the war, Robert Oppenheimer

remarked that the physicists involved in the Manhattan project had

"known sin". Von Neumann's response was that "sometimes someone

confesses a sin in order to take credit for it."

Von Neumann continued unperturbed in his work and became, along with Edward Teller, one of those who sustained the hydrogen bomb project. He collaborated with Klaus Fuchs

on further development of the bomb, and in 1946 the two filed a secret

patent on "Improvement in Methods and Means for Utilizing Nuclear

Energy", which outlined a scheme for using a fission bomb to compress

fusion fuel to initiate nuclear fusion. The Fuchs–von Neumann patent used radiation implosion, but not in the same way as is used in what became the final hydrogen bomb design, the Teller–Ulam design. Their work was, however, incorporated into the "George" shot of Operation Greenhouse, which was instructive in testing out concepts that went into the final design. The Fuchs–von Neumann work was passed on to the Soviet Union by Fuchs as part of his nuclear espionage, but it was not used in the Soviets' own, independent development of the Teller–Ulam design. The historian Jeremy Bernstein

has pointed out that ironically, "John von Neumann and Klaus Fuchs,

produced a brilliant invention in 1946 that could have changed the whole

course of the development of the hydrogen bomb, but was not fully

understood until after the bomb had been successfully made."

For his wartime services, von Neumann was awarded the Navy Distinguished Civilian Service Award in July 1946, and the Medal for Merit in October 1946.

Atomic Energy Commission

In 1950, von Neumann became a consultant to the Weapons Systems Evaluation Group (WSEG), whose function was to advise the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the United States Secretary of Defense on the development and use of new technologies. He also became an adviser to the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project

(AFSWP), which was responsible for the military aspects on nuclear

weapons. Over the following two years, he became a consultant to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), a member of the influential General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission, a consultant to the newly established Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, and a member of the Scientific Advisory Group of the United States Air Force.

In 1955, von Neumann became a commissioner of the AEC. He

accepted this position and used it to further the production of compact hydrogen bombs suitable for Intercontinental ballistic missile delivery. He involved himself in correcting the severe shortage of tritium and lithium 6

needed for these compact weapons, and he argued against settling for

the intermediate-range missiles that the Army wanted. He was adamant

that H-bombs delivered into the heart of enemy territory by an ICBM

would be the most effective weapon possible, and that the relative

inaccuracy of the missile wouldn't be a problem with an H-bomb. He said

the Russians would probably be building a similar weapon system, which

turned out to be the case.

Despite his disagreement with Oppenheimer over the need for a crash

program to develop the hydrogen bomb, he testified on the latter's

behalf at the 1954 Oppenheimer security hearing, at which he asserted that Oppenheimer was loyal, and praised him for his helpfulness once the program went ahead.

Shortly before his death from cancer, von Neumann headed the

United States government's top secret ICBM committee, which would

sometimes meet in his home. Its purpose was to decide on the feasibility

of building an ICBM large enough to carry a thermonuclear weapon. Von

Neumann had long argued that while the technical obstacles were sizable,

they could be overcome in time. The SM-65 Atlas

passed its first fully functional test in 1959, two years after his

death. The feasibility of an ICBM owed as much to improved, smaller

warheads as it did to developments in rocketry, and his understanding of

the former made his advice invaluable.

Mutual assured destruction

Operation Redwing nuclear test in July 1956

Von Neumann is credited with developing the equilibrium strategy of mutual assured destruction

(MAD). He also "moved heaven and earth" to bring MAD about. His goal

was to quickly develop ICBMs and the compact hydrogen bombs that they

could deliver to the USSR, and he knew the Soviets were doing similar

work because the CIA

interviewed German rocket scientists who were allowed to return to

Germany, and von Neumann had planted a dozen technical people in the

CIA. The Soviets considered that bombers would soon be vulnerable, and

they shared von Neumann's view that an H-bomb in an ICBM was the ne plus ultra

of weapons; they believed that whoever had superiority in these weapons

would take over the world, without necessarily using them. He was afraid of a "missile gap" and took several more steps to achieve his goal of keeping up with the Soviets:

- He modified the ENIAC by making it programmable and then wrote programs for it to do the H-bomb calculations verifying that the Teller-Ulam design was feasible and to develop it further.

- Through the Atomic Energy Commission, he promoted the development of a compact H-bomb that would fit in an ICBM.

- He personally interceded to speed up the production of lithium-6 and tritium needed for the compact bombs.

- He caused several separate missile projects to be started, because he felt that competition combined with collaboration got the best results.

Von Neumann's assessment that the Soviets had a lead in missile

technology, considered pessimistic at the time, was soon proven correct

in the Sputnik crisis.

Von Neumann entered government service primarily because he felt

that, if freedom and civilization were to survive, it would have to be

because the United States would triumph over totalitarianism from Nazism, Fascism and Soviet Communism. During a Senate committee hearing he described his political ideology as "violently anti-communist,

and much more militaristic than the norm". He was quoted in 1950

remarking, "If you say why not bomb [the Soviets] tomorrow, I say, why

not today? If you say today at five o'clock, I say why not one o'clock?"

On February 15, 1956, von Neumann was presented with the Medal of Freedom by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. His citation read:

Dr. von Neumann, in a series of scientific study projects of major national significance, has materially increased the scientific progress of this country in the armaments field.

Through his work on various highly classified missions performed outside the continental limits of the United States in conjunction with critically important international programs, Dr. von Neumann has resolved some of the most difficult technical problems of national defense.

Computing

Von Neumann was a founding figure in computing. Von Neumann was the inventor, in 1945, of the merge sort algorithm, in which the first and second halves of an array are each sorted recursively and then merged.

Von Neumann wrote the 23 pages long sorting program for the EDVAC in ink. On the first page, traces of the phrase "TOP SECRET", which was written in pencil and later erased, can still be seen. He also worked on the philosophy of artificial intelligence with Alan Turing when the latter visited Princeton in the 1930s.

Von Neumann's hydrogen bomb work was played out in the realm of

computing, where he and Stanisław Ulam developed simulations on von

Neumann's digital computers for the hydrodynamic computations. During

this time he contributed to the development of the Monte Carlo method, which allowed solutions to complicated problems to be approximated using random numbers.

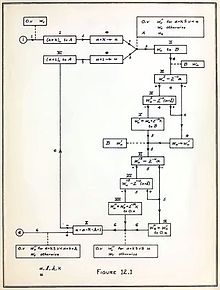

Flow chart from von Neumann's "Planning and coding of problems for an electronic computing instrument," published in 1947.

Von Neumann's algorithm for simulating a fair coin with a biased coin is used in the "software whitening" stage of some hardware random number generators. Because using lists of "truly" random numbers was extremely slow, von Neumann developed a form of making pseudorandom numbers, using the middle-square method.

Though this method has been criticized as crude, von Neumann was aware

of this: he justified it as being faster than any other method at his

disposal, writing that "Anyone who considers arithmetical methods of

producing random digits is, of course, in a state of sin."

Von Neumann also noted that when this method went awry it did so

obviously, unlike other methods which could be subtly incorrect.

While consulting for the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania on the EDVAC project, von Neumann wrote an incomplete First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC. The paper, whose premature distribution nullified the patent claims of EDVAC designers J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, described a computer architecture

in which the data and the program are both stored in the computer's

memory in the same address space. This architecture is the basis of most

modern computer designs, unlike the earliest computers that were

"programmed" using a separate memory device such as a paper tape or plugboard. Although the single-memory, stored program architecture is commonly called von Neumann architecture as a result of von Neumann's paper, the architecture was based on the work of Eckert and Mauchly, inventors of the ENIAC computer at the University of Pennsylvania.

John von Neumann consulted for the Army's Ballistic Research Laboratory, most notably on the ENIAC project, as a member of its Scientific Advisory Committee.

The electronics of the new ENIAC ran at one-sixth the speed, but this in

no way degraded the ENIAC's performance, since it was still entirely I/O bound. Complicated programs could be developed and debugged

in days rather than the weeks required for plugboarding the old ENIAC.

Some of von Neumann's early computer programs have been preserved.

The next computer that von Neumann designed was the IAS machine

at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He

arranged its financing, and the components were designed and built at

the RCA Research Laboratory nearby. John von Neumann recommended that the IBM 701, nicknamed the defense computer, include a magnetic drum. It was a faster version of the IAS machine and formed the basis for the commercially successful IBM 704.

Stochastic computing was first introduced in a pioneering paper by von Neumann in 1953.

However, the theory could not be implemented until advances in computing of the 1960s.

Cellular automata, DNA and the universal constructor

The first implementation of von Neumann's self-reproducing universal constructor.

Three generations of machine are shown: the second has nearly finished

constructing the third. The lines running to the right are the tapes of

genetic instructions, which are copied along with the body of the

machines.

A

simple configuration in von Neumann's cellular automaton. A binary

signal is passed repeatedly around the blue wire loop, using excited and

quiescent ordinary transmission states. A confluent cell duplicates the signal onto a length of red wire consisting of special transmission states.

The signal passes down this wire and constructs a new cell at the end.

This particular signal (1011) codes for an east-directed special

transmission state, thus extending the red wire by one cell each time.

During construction, the new cell passes through several sensitised

states, directed by the binary sequence.

Von Neumann's rigorous mathematical analysis of the structure of self-replication

(of the semiotic relationship between constructor, description and that

which is constructed), preceded the discovery of the structure of DNA.

Von Neumann created the field of cellular automata without the aid of computers, constructing the first self-replicating automata with pencil and graph paper.

The detailed proposal for a physical non-biological

self-replicating system was first put forward in lectures von Neumann

delivered in 1948 and 1949, when he first only proposed a kinematic self-reproducing automaton.

While qualitatively sound, von Neumann was evidently dissatisfied with

this model of a self-replicator due to the difficulty of analyzing it

with mathematical rigor. He went on to instead develop a more abstract

model self-replicator based on his original concept of cellular automata.

Subsequently, the concept of the Von Neumann universal constructor based on the von Neumann cellular automaton was fleshed out in his posthumously published lectures Theory of Self Reproducing Automata.

Ulam and von Neumann created a method for calculating liquid motion in

the 1950s. The driving concept of the method was to consider a liquid as

a group of discrete units and calculate the motion of each based on its

neighbors' behaviors. Like Ulam's lattice network, von Neumann's cellular automata are two-dimensional, with his self-replicator implemented algorithmically. The result was a universal copier and constructor

working within a cellular automaton with a small neighborhood (only

those cells that touch are neighbors; for von Neumann's cellular

automata, only orthogonal cells), and with 29 states per cell.

Von Neumann gave an existence proof that a particular pattern would

make infinite copies of itself within the given cellular universe by

designing a 200,000 cell configuration that could do so.

[T]here exists a

critical size below which the process of synthesis is degenerative, but

above which the phenomenon of synthesis, if properly arranged, can

become explosive, in other words, where syntheses of automata can

proceed in such a manner that each automaton will produce other automata

which are more complex and of higher potentialities than itself.

Von Neumann addressed the evolutionary growth of complexity amongst his self-replicating machines.

His "proof-of-principle" designs showed how it is logically possible,

by using a general purpose programmable ("universal") constructor, to

exhibit an indefinitely large class of self-replicators, spanning a wide

range of complexity, interconnected by a network of potential

mutational pathways, including pathways from the most simple to the most

complex. This is an important result, as prior to that it might have

been conjectured that there is a fundamental logical barrier to the

existence of such pathways; in which case, biological organisms, which

do support such pathways, could not be "machines", as conventionally

understood. Von Neumman considers the potential for conflict between his

self-reproducing machines, stating that "our models lead to such

conflict situations", indicating it as a field of further study.

The cybernetics

movement highlighted the question of what it takes for

self-reproduction to occur autonomously, and in 1952, John von Neumann

designed an elaborate 2D cellular automaton that would automatically make a copy of its initial configuration of cells. The von Neumann neighborhood,

in which each cell in a two-dimensional grid has the four orthogonally

adjacent grid cells as neighbors, continues to be used for other

cellular automata. Von Neumann proved that the most effective way of

performing large-scale mining operations such as mining an entire moon or asteroid belt would be by using self-replicating spacecraft, taking advantage of their exponential growth.

Von Neumann investigated the question of whether modelling

evolution on a digital computer could solve the complexity problem in

programming.

Beginning in 1949, von Neumann's design for a self-reproducing computer program is considered the world's first computer virus, and he is considered to be the theoretical father of computer virology.

Weather systems and global warming

As

part of his research into weather forecasting, von Neumann founded the

"Meteorological Program" in Princeton in 1946, securing funding for his

project from the US Navy. Von Neumann and his appointed assistant on this project, Jule Gregory Charney, wrote the world's first climate modelling software, and used it to perform the world's first numerical weather forecasts on the ENIAC computer; von Neumann and his team published the results as Numerical Integration of the Barotropic Vorticity Equation in 1950.

Together they played a leading role in efforts to integrate sea-air

exchanges of energy and moisture into the study of climate.

Von Neumann proposed as the research program for climate modeling: "The

approach is to first try short-range forecasts, then long-range

forecasts of those properties of the circulation that can perpetuate

themselves over arbitrarily long periods of time, and only finally to

attempt forecast for medium-long time periods which are too long to

treat by simple hydrodynamic theory and too short to treat by the

general principle of equilibrium theory."

Von Neumann's research into weather systems and meteorological

prediction led him to propose manipulating the environment by spreading

colorants on the polar ice caps to enhance absorption of solar radiation (by reducing the albedo), thereby inducing global warming. Von Neumann proposed a theory of global warming as a result of the activity of humans, noting that the Earth was only 6 °F (3.3 °C) colder during the last glacial period,

he wrote in 1955: "Carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by

industry's burning of coal and oil - more than half of it during the

last generation - may have changed the atmosphere's composition

sufficiently to account for a general warming of the world by about one

degree Fahrenheit." However, von Neumann urged a degree of caution in any program of intentional human weather manufacturing: "What could be done, of course, is no index to what should

be done... In fact, to evaluate the ultimate consequences of either a

general cooling or a general heating would be a complex matter. Changes

would affect the level of the seas, and hence the habitability of the

continental coastal shelves; the evaporation of the seas, and hence

general precipitation and glaciation levels; and so on... But there is

little doubt that one could carry out the necessary analyses

needed to predict the results, intervene on any desired scale, and

ultimately achieve rather fantastic results."

The technology that is now developing and that will dominate the next decades is in conflict with traditional, and, in the main, momentarily still valid, geographical and political units and concepts. This is a maturing crisis of technology... The most hopeful answer is that the human species has been subjected to similar tests before and it seems to have a congenital ability to come through, after varying amounts of trouble.—von Neumann, 1955

Technological singularity hypothesis

The first use of the concept of a singularity in the technological context is attributed to von Neumann,

who according to Ulam discussed the "ever accelerating progress of

technology and changes in the mode of human life, which gives the

appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of

the race beyond which human affairs, as we know them, could not

continue." This concept was fleshed out later in the book Future Shock by Alvin Toffler.

Cognitive abilities

Other mathematicians were stunned by von Neumann's ability to instantaneously perform complex operations in his head. As a six-year-old, he could divide two eight-digit numbers in his head and converse in Ancient Greek. When he was sent at the age of 15 to study advanced calculus under analyst Gábor Szegő, Szegő was so astounded with the boy's talent in mathematics that he was brought to tears on their first meeting.

Nobel Laureate Hans Bethe said "I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann's does not indicate a species superior to that of man", and later Bethe wrote that "[von Neumann's] brain indicated a new species, an evolution beyond man".

Seeing von Neumann's mind at work, Eugene Wigner wrote, "one had the

impression of a perfect instrument whose gears were machined to mesh

accurately to a thousandth of an inch." Paul Halmos states that "von Neumann's speed was awe-inspiring." Israel Halperin said: "Keeping up with him was ... impossible. The feeling was you were on a tricycle chasing a racing car." Edward Teller admitted that he "never could keep up with him".

Teller also said "von Neumann would carry on a conversation with my

3-year-old son, and the two of them would talk as equals, and I

sometimes wondered if he used the same principle when he talked to the

rest of us." Peter Lax wrote "Von Neumann was addicted to thinking, and in particular to thinking about mathematics".

When George Dantzig

brought von Neumann an unsolved problem in linear programming "as I

would to an ordinary mortal", on which there had been no published

literature, he was astonished when von Neumann said "Oh, that!", before

offhandedly giving a lecture of over an hour, explaining how to solve

the problem using the hitherto unconceived theory of duality.

Lothar Wolfgang Nordheim described von Neumann as the "fastest mind I ever met", and Jacob Bronowski wrote "He was the cleverest man I ever knew, without exception. He was a genius." George Pólya, whose lectures at ETH Zürich

von Neumann attended as a student, said "Johnny was the only student I

was ever afraid of. If in the course of a lecture I stated an unsolved

problem, the chances were he'd come to me at the end of the lecture with

the complete solution scribbled on a slip of paper." Eugene Wigner writes: "'Jancsi,' I might say, 'Is angular momentum always an integer of h?'

He would return a day later with a decisive answer: 'Yes, if all

particles are at rest.'... We were all in awe of Jancsi von Neumann". Enrico Fermi told physicist Herbert L. Anderson:

"You know, Herb, Johnny can do calculations in his head ten times as

fast as I can! And I can do them ten times as fast as you can, Herb, so

you can see how impressive Johnny is!"

Halmos recounts a story told by Nicholas Metropolis, concerning the speed of von Neumann's calculations, when somebody asked von Neumann to solve the famous fly puzzle:

Two bicyclists start 20 miles apart and head toward each other, each going at a steady rate of 10 mph. At the same time a fly that travels at a steady 15 mph starts from the front wheel of the southbound bicycle and flies to the front wheel of the northbound one, then turns around and flies to the front wheel of the southbound one again, and continues in this manner till he is crushed between the two front wheels. Question: what total distance did the fly cover? The slow way to find the answer is to calculate what distance the fly covers on the first, southbound, leg of the trip, then on the second, northbound, leg, then on the third, etc., etc., and, finally, to sum the infinite series so obtained.

The quick way is to observe that the bicycles meet exactly one hour after their start, so that the fly had just an hour for his travels; the answer must therefore be 15 miles.

When the question was put to von Neumann, he solved it in an instant, and thereby disappointed the questioner: "Oh, you must have heard the trick before!" "What trick?" asked von Neumann, "All I did was sum the geometric series."

Eugene Wigner told a similar story, only with a swallow instead of a fly, and says it was Max Born who posed the question to von Neumann in the 1920s.

Von Neumann was also noted for his eidetic memory (sometimes called photographic memory). Herman Goldstine wrote:

One of his remarkable abilities was his power of absolute recall. As far as I could tell, von Neumann was able on once reading a book or article to quote it back verbatim; moreover, he could do it years later without hesitation. He could also translate it at no diminution in speed from its original language into English. On one occasion I tested his ability by asking him to tell me how A Tale of Two Cities started. Whereupon, without any pause, he immediately began to recite the first chapter and continued until asked to stop after about ten or fifteen minutes.

Von Neumann was reportedly able to memorize the pages of telephone

directories. He entertained friends by asking them to randomly call out

page numbers; he then recited the names, addresses and numbers therein.

Mathematical legacy

"It

seems fair to say that if the influence of a scientist is interpreted

broadly enough to include impact on fields beyond science proper, then

John von Neumann was probably the most influential mathematician who

ever lived," wrote Miklós Rédei in John von Neumann: Selected Letters. James Glimm wrote: "he is regarded as one of the giants of modern mathematics". The mathematician Jean Dieudonné

said that von Neumann "may have been the last representative of a

once-flourishing and numerous group, the great mathematicians who were

equally at home in pure and applied mathematics and who throughout their

careers maintained a steady production in both directions", while Peter Lax described him as possessing the "most scintillating intellect of this century". In the foreword of Miklós Rédei's Selected Letters,

Peter Lax wrote, "To gain a measure of von Neumann's achievements,

consider that had he lived a normal span of years, he would certainly

have been a recipient of a Nobel Prize in economics. And if there were

Nobel Prizes in computer science and mathematics, he would have been

honored by these, too. So the writer of these letters should be thought

of as a triple Nobel laureate or, possibly, a 3 1⁄2-fold winner, for his work in physics, in particular, quantum mechanics".

Illness and death

Von Neumann's gravestone

In 1955, von Neumann was diagnosed with what was either bone or pancreatic cancer. He was not able to accept the proximity of his own demise, and the shadow of impending death instilled great fear in him. He invited a Roman Catholic priest, Father Anselm Strittmatter, O.S.B., to visit him for consultation.

Von Neumann reportedly said, "So long as there is the possibility of

eternal damnation for nonbelievers it is more logical to be a believer

at the end", essentially saying that Pascal had a point, referring to Pascal's Wager.

He had earlier confided to his mother, "There probably has to be a God.

Many things are easier to explain if there is than if there isn't." Father Strittmatter administered the last rites to him. Some of von Neumann's friends (such as Abraham Pais and Oskar Morgenstern) said they had always believed him to be "completely agnostic".

Of this deathbed conversion, Morgenstern told Heims, "He was of course

completely agnostic all his life, and then he suddenly turned

Catholic—it doesn't agree with anything whatsoever in his attitude,

outlook and thinking when he was healthy."

Father Strittmatter recalled that even after his conversion, von

Neumann did not receive much peace or comfort from it, as he still

remained terrified of death.

Von Neumann was on his deathbed when he entertained his brother

by reciting by heart and word-for-word the first few lines of each page

of Goethe's Faust. He died at age 53 on February 8, 1957, at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., under military security lest he reveal military secrets while heavily medicated. He was buried at Princeton Cemetery in Princeton, Mercer County, New Jersey.

Honors

The von Neumann crater, on the far side of the Moon.

- The John von Neumann Theory Prize of the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS, previously TIMS-ORSA) is awarded annually to an individual (or group) who have made fundamental and sustained contributions to theory in operations research and the management sciences.