Overview

Population

aging is a shift in the distribution of a country's population towards

older ages. This is usually reflected in an increase in the population's

mean and median ages,

a decline in the proportion of the population composed of children, and

a rise in the proportion of the population composed of elderly.

Population ageing is widespread across the world. It is most advanced in

the most highly developed countries, but it is growing faster in less

developed regions, which means that older persons will be increasingly

concentrated in the less developed regions of the world.

The Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, however, concluded that

population ageing has slowed considerably in Europe and will have the

greatest future impact in Asia, especially as Asia is in stage five

(very low birth rate and low death rate) of the demographic transition model.

Among the countries currently classified by the United Nations as

more developed (with a total population of 1.2 billion in 2005), the

overall median age rose from 28 in 1950 to 40 in 2010, and is forecast

to rise to 44 by 2050. The corresponding figures for the world as a

whole are 24 in 1950, 29 in 2010, and 36 in 2050. For the less developed

regions, the median age will go from 26 in 2010 to 35 in 2050.

Population ageing arises from two (possibly related) demographic effects which are increasing longevity and declining fertility.

An increase in longevity raises the average age of the population by

increasing the numbers of surviving older people. A decline in fertility

reduces the number of babies, and as the effect continues, the numbers

of younger people in general also reduce. Of these two forces, it is

declining fertility that is the largest contributor to population ageing

in the world today.

More specifically, it is the large decline in the overall fertility

rate over the last half century that is primarily responsible for the

population ageing in the world’s most developed countries. Because many

developing countries are going through faster fertility transitions,

they will experience even faster population ageing than the currently

developed countries in the future.

The rate at which the population ages is likely to increase over the next three decades; however, few countries know whether their older populations are living the extra years of life in good or poor health. A "compression of morbidity" would imply reduced disability in old age,

whereas an expansion would see an increase in poor health with

increased longevity. Another option has been posed for a situation of

"dynamic equilibrium".

This is crucial information for governments if the limits of lifespan

continue to increase indefinitely, as some researchers believe it will. The World Health Organization's

suite of household health studies is working to provide the needed

health and well-being evidence, including, for example the World Health

Survey, and the Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). These surveys cover 308,000 respondents aged 18+ years and 81,000 aged 50+ years from 70 countries.

The Global Ageing Survey, exploring attitudes, expectations and behaviours towards later life and retirement, directed by George Leeson,

and covering 44,000 people aged 40–80 in 24 countries from across the

globe has revealed that many people are now fully aware of the ageing of

the world's population and the implications which this will have on

their lives and the lives of their children and grandchildren.

Canada has the highest per capita immigration rate in the world, partly to counter population ageing. The C. D. Howe Institute, a conservative think tank, has suggested that immigration cannot be used as a viable mean for countering population ageing. This conclusion is also seen in the work of other scholars. Demographers Peter McDonald and Rebecca Kippen

comment, "[a]s fertility sinks further below replacement level,

increasingly higher levels of annual net migration will be required to

maintain a target of even zero population growth".

Ageing around the world

The worlds older population is growing dramatically.

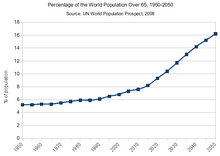

Percentage of world population over 65

This

map illustrates global trends in ageing by depicting the percentage of

each country's population that is over the age of 65. The more

developed countries also have older populations as their citizens live

longer. Less developed countries have much younger populations. An interactive version of the map is available here.

Asia and Europe

are the two regions where a significant number of countries face

population ageing in the near future. Within twenty years many countries

in these regions will face a situation where the largest population cohort

will be those over 65 and average age approach 50 years old. The Oxford

Institute of Population Ageing is an institution looking at global

population ageing. Its research reveals that many of the views of global

ageing are based on myths and that there will be considerable

opportunities for the world as its population matures. The Institute's

Director, Professor Sarah Harper highlights in her book Ageing Societies the implications for work, families, health, education, and technology of the ageing of the world's population.

Most of the developed countries now have sub-replacement fertility

levels, and population growth now depends largely on immigration

together with population momentum, which arises from previous large

generations now enjoying longer life expectancy.

Of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds—100,000 per day—die of age-related causes. In industrialized nations, the proportion is much higher, reaching 90%.

Well-being and social policies

The economic effects of an aging population are considerable. Older

people have higher accumulated savings per head than younger people, but

spend less on consumer goods. Depending on the age ranges at which the changes occur, an aging population may thus result in lower interest rates

and the economic benefits of lower inflation. Because elderly people

are more inflation averse, countries with more elderly tend to exhibit

lower inflation rates.

Some economists (Japan) see advantages in such changes, notably the

opportunity to progress automation and technological development without

causing unemployment. They emphasize a shift from GDP to personal well-being.

However, population aging also increases some categories of

expenditure, including some met from public finances. The largest area

of expenditure in many countries is now health care,

whose cost is likely to increase dramatically as populations age. This

would present governments with hard choices between higher taxes,

including a possible reweighing of tax from earnings to consumption,

and a reduced government role in providing health care. However, recent

studies in some countries demonstrate the dramatic rising costs of

health care are more attributable to rising drug and doctor costs, and

higher use of diagnostic testing by all age groups, and not to the aging

population as is often claimed.

The second-largest expenditure of most governments is education and these expenses will tend to fall with an aging population, especially as fewer young people would probably continue into tertiary education as they would be in demand as part of the work force.

Social security systems have also begun to experience problems. Earlier defined benefit pension systems

are experiencing sustainability problems due to the increased

longevity. The extension of the pension period was not paired with an

extension of the active labour period or a rise in pension

contributions, resulting in a decline of replacement ratios.

The expectation of continuing population aging prompts questions

about welfare states’ capacity to meet the needs of their population. In

the early 2000s, the World Health Organization set up guidelines to

encourage “active aging” and to help local governments address the

challenges of an aging population (Global Age-Friendly Cities) with

regard to urbanization, housing, transportation, social participation,

health services, etc.

Local governments are well positioned to meet the needs of local,

smaller populations, but as their resources vary from one to another

(e.g. property taxes, the existence of community organizations), the

greater responsibility on local governments is likely to increase

inequalities.

In Canada, the most fortunate and healthier elders tend to live in more

prosperous cities offering a wide range of services, whereas the less

fortunate don’t have access to the same level of resources.

Private residences for the elderly also provide many services related

to health and social participation (e.g. pharmacy, group activities and

events) on site; however they are not accessible to the less fortunate..

Also, the Environmental gerontology indicates the importance of the environment in active aging.

In fact, promoting good environments (natural, built, social) in aging

can improve health and quality of life, as well as reduce the problems

of disability and dependence, and, in general, social spending and

health spending.

An aging population may provide incentive for technological

progress, as some hypothesize the effect of a shrinking workforce may be

offset by technological unemployment or productivity gains.

Generally in West Africa and specifically in Ghana, social policy implications of demographic

aging are multidimensional, (such as rural-urban distribution, gender

composition, levels of literacy/illiteracy as well as their occupational

histories and income security).

Current policies on aging in Ghana, seem to be disjointed, in which

there are ideas on documents on how we can improve policies in

population aging, however these ideas are yet to be concretely

implemented perhaps due to many arguments for example that older people are only a small proportion of the population.

Due to the aging population, globally, many countries seem to be

increasing the age for old age security from 60 to 65, to decrease the

cost of the scheme of the GDP.

Age Discrimination can be defined as "the systematic and

institutionalized denial of the rights of older people on the basis of

their age by individuals, groups, organizations and institutions".

Some of this abuse can be a result of ignorance, thoughtlessness,

prejudice and stereotyping. Forms of discrimination: economic

accessibility, social accessibility, temporal accessibility and

administrative accessibility.

In the majority of the countries worldwide, particularly

countries in Africa, older people are typically the poorest members of

the social spectrum, living below the poverty line.