| Tornado | |

|---|---|

A tornado approaching Marquette, Kansas.

| |

| Season | Primarily spring and summer, but can be at any time of year |

| Effect | Wind damage |

A tornado is a rapidly rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. The windstorm is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, although the word cyclone is used in meteorology to name a weather system with a low-pressure area in the center around which, from an observer looking down toward the surface of the earth, winds blow counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern. Tornadoes come in many shapes and sizes, and they are often visible in the form of a condensation funnel originating from the base of a cumulonimbus cloud, with a cloud of rotating debris and dust beneath it. Most tornadoes have wind speeds less than 110 miles per hour (180 km/h), are about 250 feet (80 m) across, and travel a few miles (several kilometers) before dissipating. The most extreme tornadoes can attain wind speeds of more than 300 miles per hour (480 km/h), are more than two miles (3 km) in diameter, and stay on the ground for dozens of miles (more than 100 km).

Various types of tornadoes include the multiple vortex tornado, landspout, and waterspout. Waterspouts are characterized by a spiraling funnel-shaped wind current, connecting to a large cumulus or cumulonimbus cloud. They are generally classified as non-supercellular tornadoes that develop over bodies of water, but there is disagreement over whether to classify them as true tornadoes. These spiraling columns of air frequently develop in tropical areas close to the equator and are less common at high latitudes. Other tornado-like phenomena that exist in nature include the gustnado, dust devil, fire whirl, and steam devil.

Tornadoes occur most frequently in North America, particularly in central and southeastern regions of the United States colloquially known as tornado alley, as well as in Southern Africa, northwestern and southeast Europe, western and southeastern Australia, New Zealand, Bangladesh and adjacent eastern India, and southeastern South America. Tornadoes can be detected before or as they occur through the use of Pulse-Doppler radar by recognizing patterns in velocity and reflectivity data, such as hook echoes or debris balls, as well as through the efforts of storm spotters.

There are several scales for rating the strength of tornadoes. The Fujita scale rates tornadoes by damage caused and has been replaced in some countries by the updated Enhanced Fujita Scale. An F0 or EF0 tornado, the weakest category, damages trees, but not substantial structures. An F5 or EF5 tornado, the strongest category, rips buildings off their foundations and can deform large skyscrapers. The similar TORRO scale ranges from a T0 for extremely weak tornadoes to T11 for the most powerful known tornadoes. Doppler radar data, photogrammetry, and ground swirl patterns (trochoidal marks) may also be analyzed to determine intensity and assign a rating.

A tornado near Anadarko, Oklahoma, 1999. The funnel is the thin tube reaching from the cloud to the ground. The lower part of this tornado is surrounded by a translucent

dust cloud, kicked up by the tornado's strong winds at the surface. The

wind of the tornado has a much wider radius than the funnel itself.

All tornadoes in the Contiguous United States, 1950–2013, plotted by midpoint, highest F-scale on top, Alaska and Hawaii negligible, source NOAA Storm Prediction Center.

Etymology

The word tornado comes from the Spanish word tornado (past participle of to turn, or to have torn). Tornadoes' opposite phenomena are the derechoes (/dəˈreɪtʃoʊ/, from Spanish: derecho [deˈɾetʃo],

"straight"). A tornado is also commonly referred to as a "twister", and

is also sometimes referred to by the old-fashioned colloquial term cyclone. The term "cyclone" is used as a synonym for "tornado" in the often-aired 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. The term "twister" is also used in that film, along with being the title of the 1996 tornado-related film Twister.

Definitions

A tornado is "a violently rotating column of air, in contact with the ground, either pendant from a cumuliform cloud or underneath a cumuliform cloud, and often (but not always) visible as a funnel cloud".

For a vortex to be classified as a tornado, it must be in contact with

both the ground and the cloud base. Scientists have not yet created a

complete definition of the word; for example, there is disagreement as

to whether separate touchdowns of the same funnel constitute separate

tornadoes. Tornado refers to the vortex of wind, not the condensation cloud.

Funnel cloud

This

tornado has no funnel cloud; however, the rotating dust cloud indicates

that strong winds are occurring at the surface, and thus it is a true

tornado.

A tornado is not necessarily visible; however, the intense low pressure caused by the high wind speeds (as described by Bernoulli's principle) and rapid rotation (due to cyclostrophic balance) usually cause water vapor in the air to condense into cloud droplets due to adiabatic cooling. This results in the formation of a visible funnel cloud or condensation funnel.

There is some disagreement over the definition of a funnel cloud and a condensation funnel. According to the Glossary of Meteorology,

a funnel cloud is any rotating cloud pendant from a cumulus or

cumulonimbus, and thus most tornadoes are included under this

definition.

Among many meteorologists, the 'funnel cloud' term is strictly defined

as a rotating cloud which is not associated with strong winds at the

surface, and condensation funnel is a broad term for any rotating cloud

below a cumuliform cloud.

Tornadoes often begin as funnel clouds with no associated strong

winds at the surface, and not all funnel clouds evolve into tornadoes.

Most tornadoes produce strong winds at the surface while the visible

funnel is still above the ground, so it is difficult to discern the

difference between a funnel cloud and a tornado from a distance.

Outbreaks and families

Occasionally, a single storm will produce more than one tornado,

either simultaneously or in succession. Multiple tornadoes produced by

the same storm cell are referred to as a "tornado family".

Several tornadoes are sometimes spawned from the same large-scale storm

system. If there is no break in activity, this is considered a tornado

outbreak (although the term "tornado outbreak" has various definitions).

A period of several successive days with tornado outbreaks in the same

general area (spawned by multiple weather systems) is a tornado outbreak

sequence, occasionally called an extended tornado outbreak.

Characteristics

Size and shape

A wedge tornado, nearly a mile wide, which hit Binger, Oklahoma in 1981

Most tornadoes take on the appearance of a narrow funnel,

a few hundred yards (meters) across, with a small cloud of debris near

the ground. Tornadoes may be obscured completely by rain or dust. These

tornadoes are especially dangerous, as even experienced meteorologists

might not see them. Tornadoes can appear in many shapes and sizes.

Small, relatively weak landspouts may be visible only as a small

swirl of dust on the ground. Although the condensation funnel may not

extend all the way to the ground, if associated surface winds are

greater than 40 mph (64 km/h), the circulation is considered a tornado.

A tornado with a nearly cylindrical profile and relative low height is

sometimes referred to as a "stovepipe" tornado. Large single-vortex

tornadoes can look like large wedges

stuck into the ground, and so are known as "wedge tornadoes" or

"wedges". The "stovepipe" classification is also used for this type of

tornado if it otherwise fits that profile. A wedge can be so wide that

it appears to be a block of dark clouds, wider than the distance from

the cloud base to the ground. Even experienced storm observers may not

be able to tell the difference between a low-hanging cloud and a wedge

tornado from a distance. Many, but not all major tornadoes are wedges.

A rope tornado in its dissipating stage, found near Tecumseh, Oklahoma.

Tornadoes

in the dissipating stage can resemble narrow tubes or ropes, and often

curl or twist into complex shapes. These tornadoes are said to be

"roping out", or becoming a "rope tornado". When they rope out, the

length of their funnel increases, which forces the winds within the

funnel to weaken due to conservation of angular momentum.

Multiple-vortex tornadoes can appear as a family of swirls circling a

common center, or they may be completely obscured by condensation, dust,

and debris, appearing to be a single funnel.

In the United States, tornadoes are around 500 feet (150 m) across on average and travel on the ground for 5 miles (8.0 km).

However, there is a wide range of tornado sizes. Weak tornadoes, or

strong yet dissipating tornadoes, can be exceedingly narrow, sometimes

only a few feet or couple meters across. One tornado was reported to

have a damage path only 7 feet (2.1 m) long. On the other end of the spectrum, wedge tornadoes can have a damage path a mile (1.6 km) wide or more. A tornado that affected Hallam, Nebraska on May 22, 2004, was up to 2.5 miles (4.0 km) wide at the ground, and a tornado in El Reno, Oklahoma on May 31, 2013 was approximately 2.6 miles (4.2 km) wide, the widest on record.

In terms of path length, the Tri-State Tornado, which affected parts of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana

on March 18, 1925, was on the ground continuously for 219 miles

(352 km). Many tornadoes which appear to have path lengths of 100 miles

(160 km) or longer are composed of a family of tornadoes which have

formed in quick succession; however, there is no substantial evidence

that this occurred in the case of the Tri-State Tornado.

In fact, modern reanalysis of the path suggests that the tornado may

have begun 15 miles (24 km) further west than previously thought.

Appearance

Tornadoes can have a wide range of colors, depending on the

environment in which they form. Those that form in dry environments can

be nearly invisible, marked only by swirling debris at the base of the

funnel. Condensation funnels that pick up little or no debris can be

gray to white. While traveling over a body of water (as a waterspout),

tornadoes can turn white or even blue. Slow-moving funnels, which ingest

a considerable amount of debris and dirt, are usually darker, taking on

the color of debris. Tornadoes in the Great Plains

can turn red because of the reddish tint of the soil, and tornadoes in

mountainous areas can travel over snow-covered ground, turning white.

Photographs of the Waurika, Oklahoma

tornado of May 30, 1976, taken at nearly the same time by two

photographers. In the top picture, the tornado is lit with the sunlight

focused from behind the camera,

thus the funnel appears bluish. In the lower image, where the camera is

facing the opposite direction, the sun is behind the tornado, giving it

a dark appearance.

Lighting conditions are a major factor in the appearance of a tornado. A tornado which is "back-lit"

(viewed with the sun behind it) appears very dark. The same tornado,

viewed with the sun at the observer's back, may appear gray or brilliant

white. Tornadoes which occur near the time of sunset can be many

different colors, appearing in hues of yellow, orange, and pink.

Dust kicked up by the winds of the parent thunderstorm, heavy

rain and hail, and the darkness of night are all factors which can

reduce the visibility of tornadoes. Tornadoes occurring in these

conditions are especially dangerous, since only weather radar

observations, or possibly the sound of an approaching tornado, serve as

any warning to those in the storm's path. Most significant tornadoes

form under the storm's updraft base, which is rain-free, making them visible. Also, most tornadoes occur in the late afternoon, when the bright sun can penetrate even the thickest clouds. Night-time tornadoes are often illuminated by frequent lightning.

There is mounting evidence, including Doppler on Wheels

mobile radar images and eyewitness accounts, that most tornadoes have a

clear, calm center with extremely low pressure, akin to the eye of tropical cyclones. Lightning is said to be the source of illumination for those who claim to have seen the interior of a tornado.

Rotation

Tornadoes normally rotate cyclonically (when viewed from above, this is counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern). While large-scale storms always rotate cyclonically due to the Coriolis effect,

thunderstorms and tornadoes are so small that the direct influence of

the Coriolis effect is unimportant, as indicated by their large Rossby numbers. Supercells and tornadoes rotate cyclonically in numerical simulations even when the Coriolis effect is neglected. Low-level mesocyclones and tornadoes owe their rotation to complex processes within the supercell and ambient environment.

Approximately 1 percent of tornadoes rotate in an anticyclonic

direction in the northern hemisphere. Typically, systems as weak as

landspouts and gustnadoes can rotate anticyclonically, and usually only

those which form on the anticyclonic shear side of the descending rear flank downdraft (RFD) in a cyclonic supercell. On rare occasions, anticyclonic tornadoes

form in association with the mesoanticyclone of an anticyclonic

supercell, in the same manner as the typical cyclonic tornado, or as a

companion tornado either as a satellite tornado or associated with

anticyclonic eddies within a supercell.

Sound and seismology

An illustration of generation of infrasound in tornadoes by the Earth System Research Laboratory's Infrasound Program

Tornadoes emit widely on the acoustics spectrum

and the sounds are caused by multiple mechanisms. Various sounds of

tornadoes have been reported, mostly related to familiar sounds for the

witness and generally some variation of a whooshing roar. Popularly

reported sounds include a freight train, rushing rapids or waterfall, a

nearby jet engine, or combinations of these. Many tornadoes are not

audible from much distance; the nature of and the propagation distance

of the audible sound depends on atmospheric conditions and topography.

The winds of the tornado vortex and of constituent turbulent eddies,

as well as airflow interaction with the surface and debris, contribute

to the sounds. Funnel clouds also produce sounds. Funnel clouds and

small tornadoes are reported as whistling, whining, humming, or the

buzzing of innumerable bees or electricity, or more or less harmonic,

whereas many tornadoes are reported as a continuous, deep rumbling, or

an irregular sound of "noise".

Since many tornadoes are audible only when very near, sound is

not to be thought of as a reliable warning signal for a tornado.

Tornadoes are also not the only source of such sounds in severe

thunderstorms; any strong, damaging wind, a severe hail volley, or

continuous thunder in a thunderstorm may produce a roaring sound.

Tornadoes also produce identifiable inaudible infrasonic signatures.

Unlike audible signatures, tornadic signatures have been

isolated; due to the long distance propagation of low-frequency sound,

efforts are ongoing to develop tornado prediction and detection devices

with additional value in understanding tornado morphology, dynamics, and

creation. Tornadoes also produce a detectable seismic signature, and research continues on isolating it and understanding the process.

Electromagnetic, lightning, and other effects

Tornadoes emit on the electromagnetic spectrum, with sferics and E-field effects detected.[45][47][48]

There are observed correlations between tornadoes and patterns of

lightning. Tornadic storms do not contain more lightning than other

storms and some tornadic cells never produce lightning at all. More

often than not, overall cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning activity

decreases as a tornado touches the surface and returns to the baseline

level when the tornado dissipates. In many cases, intense tornadoes and

thunderstorms exhibit an increased and anomalous dominance of positive

polarity CG discharges. Electromagnetics and lightning have little or nothing to do directly with what drives tornadoes (tornadoes are basically a thermodynamic phenomenon), although there are likely connections with the storm and environment affecting both phenomena.

Luminosity

has been reported in the past and is probably due to misidentification

of external light sources such as lightning, city lights, and power flashes

from broken lines, as internal sources are now uncommonly reported and

are not known to ever have been recorded. In addition to winds,

tornadoes also exhibit changes in atmospheric variables such as temperature, moisture, and pressure. For example, on June 24, 2003 near Manchester, South Dakota, a probe measured a 100 mbar (hPa) (2.95 inHg) pressure decrease. The pressure dropped gradually as the vortex approached then dropped extremely rapidly to 850 mbar (hPa) (25.10 inHg)

in the core of the violent tornado before rising rapidly as the vortex

moved away, resulting in a V-shape pressure trace. Temperature tends to

decrease and moisture content to increase in the immediate vicinity of a

tornado.

Life cycle

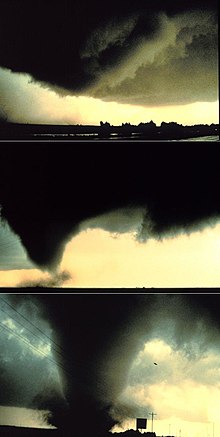

A

sequence of images showing the birth of a tornado. First, the rotating

cloud base lowers. This lowering becomes a funnel, which continues

descending while winds build near the surface, kicking up dust and

debris and causing damage. As the pressure continues to drop, the

visible funnel extends to the ground. This tornado, near Dimmitt, Texas, was one of the best-observed violent tornadoes in history.

Supercell relationship

Tornadoes often develop from a class of thunderstorms known as supercells. Supercells contain mesocyclones,

an area of organized rotation a few miles up in the atmosphere, usually

1–6 miles (1.6–9.7 kilometres) across. Most intense tornadoes (EF3 to

EF5 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale)

develop from supercells. In addition to tornadoes, very heavy rain,

frequent lightning, strong wind gusts, and hail are common in such

storms.

Most tornadoes from supercells follow a recognizable life cycle.

That begins when increasing rainfall drags with it an area of quickly

descending air known as the rear flank downdraft (RFD). This downdraft

accelerates as it approaches the ground, and drags the supercell's

rotating mesocyclone towards the ground with it.

Composite of eight images shot in sequence as a tornado formed in Kansas in 2016

Formation

As the mesocyclone lowers below the cloud base, it begins to take in

cool, moist air from the downdraft region of the storm. The convergence

of warm air in the updraft and cool air causes a rotating wall cloud to

form. The RFD also focuses the mesocyclone's base, causing it to draw

air from a smaller and smaller area on the ground. As the updraft

intensifies, it creates an area of low pressure at the surface. This

pulls the focused mesocyclone down, in the form of a visible

condensation funnel. As the funnel descends, the RFD also reaches the

ground, fanning outward and creating a gust front that can cause severe

damage a considerable distance from the tornado. Usually, the funnel

cloud begins causing damage on the ground (becoming a tornado) within a

few minutes of the RFD reaching the ground.

Maturity

Initially, the tornado has a good source of warm, moist air flowing inward

to power it, and it grows until it reaches the "mature stage". This can

last anywhere from a few minutes to more than an hour, and during that

time a tornado often causes the most damage, and in rare cases can be

more than one mile (1.6 km) across. The low pressured atmosphere at the

base of the tornado is essential to the endurance of the system.

Meanwhile, the RFD, now an area of cool surface winds, begins to wrap

around the tornado, cutting off the inflow of warm air which previously

fed the tornado.

Dissipation

As the RFD completely wraps around and chokes off the tornado's air

supply, the vortex begins to weaken, and become thin and rope-like. This

is the "dissipating stage", often lasting no more than a few minutes,

after which the tornado ends. During this stage the shape of the tornado

becomes highly influenced by the winds of the parent storm, and can be

blown into fantastic patterns.

Even though the tornado is dissipating, it is still capable of causing

damage. The storm is contracting into a rope-like tube and, due to conservation of angular momentum, winds can increase at this point.

As the tornado enters the dissipating stage, its associated

mesocyclone often weakens as well, as the rear flank downdraft cuts off

the inflow powering it. Sometimes, in intense supercells, tornadoes can

develop cyclically.

As the first mesocyclone and associated tornado dissipate, the storm's

inflow may be concentrated into a new area closer to the center of the

storm and possibly feed a new mesocyclone. If a new mesocyclone

develops, the cycle may start again, producing one or more new

tornadoes. Occasionally, the old (occluded) mesocyclone and the new

mesocyclone produce a tornado at the same time.

Although this is a widely accepted theory for how most tornadoes

form, live, and die, it does not explain the formation of smaller

tornadoes, such as landspouts, long-lived tornadoes, or tornadoes with

multiple vortices. These each have different mechanisms which influence

their development—however, most tornadoes follow a pattern similar to

this one.

Types

Multiple vortex

A multiple-vortex tornado outside Dallas, Texas on April 2, 1957.

A multiple-vortex tornado is a type of tornado in which two or

more columns of spinning air rotate about their own axis and at the

same time around a common center. A multi-vortex structure can occur in

almost any circulation, but is very often observed in intense tornadoes.

These vortices often create small areas of heavier damage along the

main tornado path. This is a phenomenon that is distinct from a satellite tornado,

which is a smaller tornado which forms very near a large, strong

tornado contained within the same mesocyclone. The satellite tornado may

appear to "orbit"

the larger tornado (hence the name), giving the appearance of one,

large multi-vortex tornado. However, a satellite tornado is a distinct

circulation, and is much smaller than the main funnel.

Waterspout

A waterspout near the Florida Keys in 1969.

A waterspout is defined by the National Weather Service

as a tornado over water. However, researchers typically distinguish

"fair weather" waterspouts from tornadic (i.e. associated with a

mesocyclone) waterspouts. Fair weather waterspouts are less severe but

far more common, and are similar to dust devils and landspouts. They form at the bases of cumulus congestus clouds over tropical and subtropical waters. They have relatively weak winds, smooth laminar walls, and typically travel very slowly. They occur most commonly in the Florida Keys and in the northern Adriatic Sea.

In contrast, tornadic waterspouts are stronger tornadoes over water.

They form over water similarly to mesocyclonic tornadoes, or are

stronger tornadoes which cross over water. Since they form from severe thunderstorms and can be far more intense, faster, and longer-lived than fair weather waterspouts, they are more dangerous.

In official tornado statistics, waterspouts are generally not counted

unless they affect land, though some European weather agencies count

waterspouts and tornadoes together.

Landspout

A landspout, or dust-tube tornado, is a tornado not

associated with a mesocyclone. The name stems from their

characterization as a "fair weather waterspout on land". Waterspouts and

landspouts share many defining characteristics, including relative

weakness, short lifespan, and a small, smooth condensation funnel which

often does not reach the surface. Landspouts also create a distinctively

laminar cloud of dust when they make contact with the ground, due to

their differing mechanics from true mesoform tornadoes. Though usually

weaker than classic tornadoes, they can produce strong winds which could

cause serious damage.

Similar circulations

Gustnado

A gustnado, or gust front tornado, is a small, vertical swirl associated with a gust front or downburst.

Because they are not connected with a cloud base, there is some debate

as to whether or not gustnadoes are tornadoes. They are formed when fast

moving cold, dry outflow air from a thunderstorm

is blown through a mass of stationary, warm, moist air near the outflow

boundary, resulting in a "rolling" effect (often exemplified through a roll cloud). If low level wind shear

is strong enough, the rotation can be turned vertically or diagonally

and make contact with the ground. The result is a gustnado. They usually cause small areas of heavier rotational wind damage among areas of straight-line wind damage.

Dust devil

A dust devil in Arizona

A dust devil (also known as a whirlwind) resembles a tornado

in that it is a vertical swirling column of air. However, they form

under clear skies and are no stronger than the weakest tornadoes. They

form when a strong convective updraft is formed near the ground on a hot

day. If there is enough low level wind shear, the column of hot, rising

air can develop a small cyclonic motion that can be seen near the

ground. They are not considered tornadoes because they form during fair

weather and are not associated with any clouds. However, they can, on

occasion, result in major damage.

Fire whirls

Small-scale, tornado-like circulations can occur near any intense surface heat source. Those that occur near intense wildfires are called fire whirls. They are not considered tornadoes, except in the rare case where they connect to a pyrocumulus

or other cumuliform cloud above. Fire whirls usually are not as strong

as tornadoes associated with thunderstorms. They can, however, produce

significant damage.

Steam devils

A steam devil is a rotating updraft

between 50 and 200 meters wide that involves steam or smoke. These

formations do not involve high wind speeds, only completing a few

rotations per minute. Steam devils are very rare. They most often form

from smoke issuing from a power plant's smokestack. Hot springs

and deserts may also be suitable locations for a tighter,

faster-rotating steam devil to form. The phenomenon can occur over

water, when cold arctic air passes over relatively warm water.

Intensity and damage

The Fujita scale and the Enhanced Fujita Scale rate tornadoes by

damage caused. The Enhanced Fujita (EF) Scale was an update to the older

Fujita scale, by expert elicitation,

using engineered wind estimates and better damage descriptions. The EF

Scale was designed so that a tornado rated on the Fujita scale would

receive the same numerical rating, and was implemented starting in the

United States in 2007. An EF0 tornado will probably damage trees but not

substantial structures, whereas an EF5 tornado can rip buildings off their foundations leaving them bare and even deform large skyscrapers. The similar TORRO scale ranges from a T0 for extremely weak tornadoes to T11 for the most powerful known tornadoes. Doppler weather radar data, photogrammetry, and ground swirl patterns (cycloidal marks) may also be analyzed to determine intensity and award a rating.

A house displaying EF1 damage. The roof and garage door have been damaged, but walls and supporting structures are still intact.

Tornadoes vary in intensity regardless of shape, size, and location,

though strong tornadoes are typically larger than weak tornadoes. The

association with track length and duration also varies, although longer

track tornadoes tend to be stronger. In the case of violent tornadoes, only a small portion of the path is of violent intensity, most of the higher intensity from subvortices.

In the United States, 80% of tornadoes are EF0 and EF1 (T0

through T3) tornadoes. The rate of occurrence drops off quickly with

increasing strength—less than 1% are violent tornadoes (EF4, T8 or

stronger). Outside Tornado Alley,

and North America in general, violent tornadoes are extremely rare.

This is apparently mostly due to the lesser number of tornadoes overall,

as research shows that tornado intensity distributions are fairly

similar worldwide. A few significant tornadoes occur annually in Europe,

Asia, southern Africa, and southeastern South America, respectively.

Climatology

Areas worldwide where tornadoes are most likely, indicated by orange shading

The United States has the most tornadoes of any country, nearly four

times more than estimated in all of Europe, excluding waterspouts. This is mostly due to the unique geography of the continent. North America is a large continent that extends from the tropics north into arctic areas, and has no major east-west mountain range to block air flow between these two areas. In the middle latitudes, where most tornadoes of the world occur, the Rocky Mountains block moisture and buckle the atmospheric flow, forcing drier air at mid-levels of the troposphere due to downsloped winds, and causing the formation of a low pressure area downwind to the east of the mountains. Increased westerly flow off the Rockies force the formation of a dry line when the flow aloft is strong, while the Gulf of Mexico

fuels abundant low-level moisture in the southerly flow to its east.

This unique topography allows for frequent collisions of warm and cold

air, the conditions that breed strong, long-lived storms throughout the

year. A large portion of these tornadoes form in an area of the central United States known as Tornado Alley. This area extends into Canada, particularly Ontario and the Prairie Provinces, although southeast Quebec, the interior of British Columbia, and western New Brunswick are also tornado-prone. Tornadoes also occur across northeastern Mexico.

The United States averages about 1,200 tornadoes per year, followed by Canada, averaging 62 reported per year. NOAA's has a higher average 100 per year in Canada.

The Netherlands has the highest average number of recorded tornadoes

per area of any country (more than 20, or 0.0013 per sq mi (0.00048 per

km2), annually), followed by the UK (around 33, or 0.00035 per sq mi (0.00013 per km2), per year), although those are of lower intensity, briefer] and cause minor damage.

Intense tornado activity in the United States. The darker-colored areas denote the area commonly referred to as Tornado Alley.

Tornadoes kill an average of 179 people per year in Bangladesh, the most in the world. Reasons for this include the region's high population density, poor construction quality, and lack of tornado safety knowledge. Other areas of the world that have frequent tornadoes include South Africa, the La Plata Basin area, portions of Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and far eastern Asia.

Tornadoes are most common in spring and least common in winter,

but tornadoes can occur any time of year that favorable conditions

occur.

Spring and fall experience peaks of activity as those are the seasons

when stronger winds, wind shear, and atmospheric instability are

present. Tornadoes are focused in the right front quadrant of landfalling tropical cyclones, which tend to occur in the late summer and autumn. Tornadoes can also be spawned as a result of eyewall mesovortices, which persist until landfall.

Tornado occurrence is highly dependent on the time of day, because of solar heating. Worldwide, most tornadoes occur in the late afternoon, between 3 pm and 7 pm local time, with a peak near 5 pm. Destructive tornadoes can occur at any time of day. The Gainesville Tornado of 1936, one of the deadliest tornadoes in history, occurred at 8:30 am local time.

The United Kingdom has the highest incidence of tornadoes, measured by unit area of land, than any other country in the world.

Unsettled conditions and weather fronts transverse the Islands at all

times of the years and are responsible for spawning the tornadoes, which

consequently form at all times of the year. The United Kingdom has at

least 34 tornadoes per year and possibly as many as 50,

more than any other country in the world relative to its land area.

Most tornadoes in the United Kingdom are weak, but they are occasionally

destructive. For example, the Birmingham tornado of 2005 and the London

tornado of 2006 both registered F2 on the Fujita scale and both caused

significant damage and injury.

Associations with climate and climate change

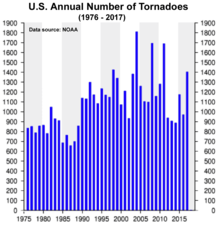

U. S. Annual January–December Tornado Count 1976–2011 from NOAA National Climatic Data Center

Associations with various climate and environmental trends exist. For example, an increase in the sea surface temperature of a source region (e.g. Gulf of Mexico and Mediterranean Sea) increases atmospheric moisture content. Increased moisture can fuel an increase in severe weather and tornado activity, particularly in the cool season.

Some evidence does suggest that the Southern Oscillation is weakly correlated with changes in tornado activity, which vary by season and region, as well as whether the ENSO phase is that of El Niño or La Niña.

Research has found that fewer tornadoes and hailstorms occur in winter

and spring in the U.S. central and southern plains during El Niño, and more occur during La Niña, than in years when temperatures in the Pacific are relatively stable. Ocean conditions could be used to forecast extreme spring storm events several months in advance.

Climatic shifts may affect tornadoes via teleconnections

in shifting the jet stream and the larger weather patterns. The

climate-tornado link is confounded by the forces affecting larger

patterns and by the local, nuanced nature of tornadoes. Although it is

reasonable to suspect that global warming may affect trends in tornado activity,

any such effect is not yet identifiable due to the complexity, local

nature of the storms, and database quality issues. Any effect would vary

by region.

Detection

Path of a tornado across Wisconsin on August 21, 1857

Rigorous attempts to warn of tornadoes began in the United States in

the mid-20th century. Before the 1950s, the only method of detecting a

tornado was by someone seeing it on the ground. Often, news of a tornado

would reach a local weather office after the storm. However, with the

advent of weather radar, areas near a local office could get advance

warning of severe weather. The first public tornado warnings were issued in 1950 and the first tornado watches and convective outlooks came about in 1952. In 1953, it was confirmed that hook echoes were associated with tornadoes.

By recognizing these radar signatures, meteorologists could detect

thunderstorms probably producing tornadoes from several miles away.

Radar

Today, most developed countries have a network of weather radars,

which serves as the primary method of detecting hook signatures that are

likely associated with tornadoes. In the United States and a few other

countries, Doppler weather radar stations are used. These devices

measure the velocity and radial direction

(towards or away from the radar) of the winds within a storm, and so

can spot evidence of rotation in storms from over one hundred miles

(160 km) away. When storms are distant from a radar, only areas high

within the storm are observed and the important areas below are not

sampled.

Data resolution also decreases with distance from the radar. Some

meteorological situations leading to tornadogenesis are not readily

detectable by radar and tornado development may occasionally take place

more quickly than radar can complete a scan and send the batch of data.

Doppler radar systems can detect mesocyclones within a supercell thunderstorm. This allows meteorologists to predict tornado formations throughout thunderstorms.

A Doppler on Wheels radar loop of a hook echo and associated mesocyclone in Goshen County, Wyoming on June 5, 2009.

Strong mesocyclones show up as adjacent areas of yellow and blue (on

other radars, bright red and bright green), and usually indicate an

imminent or occurring tornado.

Storm spotting

In the mid-1970s, the U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) increased its efforts to train storm spotters

so they could spot key features of storms that indicate severe hail,

damaging winds, and tornadoes, as well as storm damage and flash flooding. The program was called Skywarn, and the spotters were local sheriff's deputies, state troopers, firefighters, ambulance drivers, amateur radio operators, civil defense (now emergency management) spotters, storm chasers,

and ordinary citizens. When severe weather is anticipated, local

weather service offices request these spotters to look out for severe

weather and report any tornadoes immediately, so that the office can

warn of the hazard.

Spotters usually are trained by the NWS on behalf of their respective organizations, and report to them. The organizations activate public warning systems such as sirens and the Emergency Alert System (EAS), and they forward the report to the NWS.

There are more than 230,000 trained Skywarn weather spotters across the United States.

In Canada, a similar network of volunteer weather watchers, called Canwarn, helps spot severe weather, with more than 1,000 volunteers. In Europe, several nations are organizing spotter networks under the auspices of Skywarn Europe and the Tornado and Storm Research Organisation (TORRO) has maintained a network of spotters in the United Kingdom since 1974.

Storm spotters are required because radar systems such as NEXRAD do not really detect tornadoes; merely signatures which hint at the presence of tornadoes. Radar may give a warning before there is any visual evidence of a tornado or an imminent one, but ground truth from an observer can either verify the threat or determine that a tornado is not imminent.

The spotter's ability to see what radar can't is especially important

as distance from the radar site increases, because the radar beam

becomes progressively higher in altitude further away from the radar,

chiefly due to curvature of Earth, and the beam also spreads out.

Visual evidence

A rotating wall cloud with rear flank downdraft clear slot evident to its left rear

Storm spotters are trained to discern whether or not a storm seen

from a distance is a supercell. They typically look to its rear, the

main region of updraft and inflow. Under that updraft is a rain-free base, and the next step of tornadogenesis is the formation of a rotating wall cloud. The vast majority of intense tornadoes occur with a wall cloud on the backside of a supercell.

Evidence of a supercell is based on the storm's shape and

structure, and cloud tower features such as a hard and vigorous updraft

tower, a persistent, large overshooting top, a hard anvil (especially when backsheared against strong upper level winds), and a corkscrew look or striations.

Under the storm and closer to where most tornadoes are found, evidence

of a supercell and the likelihood of a tornado includes inflow bands

(particularly when curved) such as a "beaver tail", and other clues such

as strength of inflow, warmth and moistness of inflow air, how outflow-

or inflow-dominant a storm appears, and how far is the front flank

precipitation core from the wall cloud. Tornadogenesis is most likely at

the interface of the updraft and rear flank downdraft, and requires a balance between the outflow and inflow.

Only wall clouds that rotate spawn tornadoes, and they usually

precede the tornado between five and thirty minutes. Rotating wall

clouds may be a visual manifestation of a low-level mesocyclone. Barring

a low-level boundary, tornadogenesis is highly unlikely unless a rear

flank downdraft occurs, which is usually visibly evidenced by

evaporation of cloud

adjacent to a corner of a wall cloud. A tornado often occurs as this

happens or shortly afterwards; first, a funnel cloud dips and in nearly

all cases by the time it reaches halfway down, a surface swirl has

already developed, signifying a tornado is on the ground before

condensation connects the surface circulation to the storm. Tornadoes

may also develop without wall clouds, under flanking lines and on the

leading edge. Spotters watch all areas of a storm, and the cloud base and surface.

Extremes

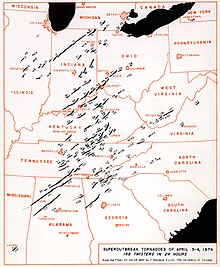

A map of the tornado paths in the Super Outbreak (April 3–4, 1974)

The most record-breaking tornado in recorded history was the Tri-State Tornado, which roared through parts of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana

on March 18, 1925. It was likely an F5, though tornadoes were not

ranked on any scale in that era. It holds records for longest path

length (219 miles; 352 km), longest duration (about 3.5 hours), and

fastest forward speed for a significant tornado (73 mph; 117 km/h)

anywhere on Earth. In addition, it is the deadliest single tornado in

United States history (695 dead).

The tornado was also the costliest tornado in history at the time

(unadjusted for inflation), but in the years since has been surpassed by

several others if population changes over time are not considered. When

costs are normalized for wealth and inflation, it ranks third today.

The deadliest tornado in world history was the Daultipur-Salturia Tornado in Bangladesh on April 26, 1989, which killed approximately 1,300 people. Bangladesh has had at least 19 tornadoes in its history kill more than 100 people, almost half of the total in the rest of the world.

The most extensive tornado outbreak on record was the 2011 Super Outbreak,

which spawned 360 confirmed tornadoes over the southeastern United

States – 216 of them within a single 24-hour period. The previous record

was the 1974 Super Outbreak which spawned 148 tornadoes.

While direct measurement of the most violent tornado wind speeds is nearly impossible, since conventional anemometers would be destroyed by the intense winds and flying debris, some tornadoes have been scanned by mobile Doppler radar units,

which can provide a good estimate of the tornado's winds. The highest

wind speed ever measured in a tornado, which is also the highest wind

speed ever recorded on the planet, is 301 ± 20 mph (484 ± 32 km/h) in

the F5 Bridge Creek-Moore, Oklahoma, tornado which killed 36 people.

Though the reading was taken about 100 feet (30 m) above the ground,

this is a testament to the power of the strongest tornadoes.

Storms that produce tornadoes can feature intense updrafts,

sometimes exceeding 150 mph (240 km/h). Debris from a tornado can be

lofted into the parent storm and carried a very long distance. A tornado

which affected Great Bend, Kansas,

in November 1915, was an extreme case, where a "rain of debris"

occurred 80 miles (130 km) from the town, a sack of flour was found 110

miles (180 km) away, and a cancelled check from the Great Bend bank was

found in a field outside of Palmyra, Nebraska, 305 miles (491 km) to the northeast. Waterspouts and tornadoes have been advanced as an explanation for instances of raining fish and other animals.

Safety

Damage from the Birmingham tornado of 2005. An unusually strong example of a tornado event in the United Kingdom, the Birmingham Tornado resulted in 19 injuries, mostly from falling trees.

Though tornadoes can strike in an instant, there are precautions and

preventative measures that people can take to increase the chances of

surviving a tornado. Authorities such as the Storm Prediction Center

advise having a pre-determined plan should a tornado warning be issued.

When a warning is issued, going to a basement or an interior

first-floor room of a sturdy building greatly increases chances of

survival. In tornado-prone areas, many buildings have storm cellars on the property. These underground refuges have saved thousands of lives.

Some countries have meteorological agencies which distribute

tornado forecasts and increase levels of alert of a possible tornado

(such as tornado watches and warnings in the United States and Canada). Weather radios

provide an alarm when a severe weather advisory is issued for the local

area, though these are mainly available only in the United States.

Unless the tornado is far away and highly visible, meteorologists advise

that drivers park their vehicles far to the side of the road (so as not

to block emergency traffic), and find a sturdy shelter. If no sturdy

shelter is nearby, getting low in a ditch is the next best option.

Highway overpasses are one of the worst places to take shelter during

tornadoes, as the constricted space can be subject to increased wind

speed and funneling of debris underneath the overpass.

Myths and misconceptions

Folklore often identifies a green sky with tornadoes, and though the

phenomenon may be associated with severe weather, there is no evidence

linking it specifically with tornadoes. It is often thought that opening windows will lessen the damage caused by the tornado. While there is a large drop in atmospheric pressure

inside a strong tornado, it is unlikely that the pressure drop would be

enough to cause the house to explode. Opening windows may actually

increase the severity of the tornado's damage. A violent tornado can destroy a house whether its windows are open or closed.

The 1999 Salt Lake City tornado disproved several misconceptions, including the idea that tornadoes cannot occur in cities.

Another commonly held misconception is that highway overpasses

provide adequate shelter from tornadoes. This belief is partly inspired

by widely circulated video captured during the 1991 tornado outbreak near Andover, Kansas, where a news crew and several other people take shelter under an overpass on the Kansas Turnpike and safely ride out a tornado as it passes by.

However, a highway overpass is a dangerous place during a tornado, and

the subjects of the video remained safe due to an unlikely combination

of events: the storm in question was a weak tornado, the tornado did not

directly strike the overpass, and the overpass itself was of a unique

design. Due to the Venturi effect, tornadic winds are accelerated in the confined space of an overpass. Indeed, in the 1999 Oklahoma tornado outbreak

of May 3, 1999, three highway overpasses were directly struck by

tornadoes, and at each of the three locations there was a fatality,

along with many life-threatening injuries.

By comparison, during the same tornado outbreak, more than 2000 homes

were completely destroyed, with another 7000 damaged, and yet only a few

dozen people died in their homes.

An old belief is that the southwest corner of a basement provides

the most protection during a tornado. The safest place is the side or

corner of an underground room opposite the tornado's direction of

approach (usually the northeast corner), or the central-most room on the

lowest floor. Taking shelter in a basement, under a staircase, or under

a sturdy piece of furniture such as a workbench further increases

chances of survival.

There are areas which people believe to be protected from

tornadoes, whether by being in a city, near a major river, hill, or

mountain, or even protected by supernatural forces. Tornadoes have been known to cross major rivers, climb mountains, affect valleys, and have damaged several city centers. As a general rule, no area is safe from tornadoes, though some areas are more susceptible than others.

Ongoing research

A Doppler on Wheels unit observing a tornado near Attica, Kansas

Meteorology is a relatively young science and the study of tornadoes

is newer still. Although researched for about 140 years and intensively

for around 60 years, there are still aspects of tornadoes which remain a

mystery. Scientists have a fairly good understanding of the development of thunderstorms and mesocyclones, and the meteorological conditions conducive to their formation. However, the step from supercell, or other respective formative processes, to tornadogenesis and the prediction of tornadic vs. non-tornadic mesocyclones is not yet well known and is the focus of much research.

Also under study are the low-level mesocyclone and the stretching of low-level vorticity which tightens into a tornado,

in particular, what are the processes and what is the relationship of

the environment and the convective storm. Intense tornadoes have been

observed forming simultaneously with a mesocyclone aloft (rather than

succeeding mesocyclogenesis) and some intense tornadoes have occurred

without a mid-level mesocyclone.

In particular, the role of downdrafts, particularly the rear-flank downdraft, and the role of baroclinic boundaries, are intense areas of study.

Reliably predicting tornado intensity and longevity remains a

problem, as do details affecting characteristics of a tornado during its

life cycle and tornadolysis. Other rich areas of research are tornadoes

associated with mesovortices within linear thunderstorm structures and within tropical cyclones.

Scientists still do not know the exact mechanisms by which most

tornadoes form, and occasional tornadoes still strike without a tornado

warning being issued. Analysis of observations including both stationary and mobile (surface and aerial) in-situ and remote sensing (passive and active) instruments generates new ideas and refines existing notions. Numerical modeling

also provides new insights as observations and new discoveries are

integrated into our physical understanding and then tested in computer simulations

which validate new notions as well as produce entirely new theoretical

findings, many of which are otherwise unattainable. Importantly,

development of new observation technologies and installation of finer

spatial and temporal resolution observation networks have aided

increased understanding and better predictions.

Research programs, including field projects such as the VORTEX projects (Verification of the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment), deployment of TOTO (the TOtable Tornado Observatory), Doppler on Wheels (DOW), and dozens of other programs, hope to solve many questions that still plague meteorologists. Universities, government agencies such as the National Severe Storms Laboratory, private-sector meteorologists, and the National Center for Atmospheric Research

are some of the organizations very active in research; with various

sources of funding, both private and public, a chief entity being the National Science Foundation.

The pace of research is partly constrained by the number of

observations that can be taken; gaps in information about the wind,

pressure, and moisture content throughout the local atmosphere; and the

computing power available for simulation.

Solar storms similar to tornadoes have been recorded, but it is

unknown how closely related they are to their terrestrial counterparts.