A coal surface mining site in Bihar, India

A mountaintop removal mining operation in the United States

The environmental impact of the coal industry includes issues such as land use, waste management, water and air pollution, caused by the coal mining,

processing and the use of its products. In addition to atmospheric

pollution, coal burning produces hundreds of millions of tons of solid

waste products annually, including fly ash, bottom ash, and flue-gas desulfurization sludge, that contain mercury, uranium, thorium, arsenic, and other heavy metals. Coal is the largest contributor to the human-made increase of CO2 in the atmosphere.

There are severe health effects caused by burning coal. According to a report by the World Health Organization in 2008, coal particulates pollution are estimated to shorten approximately 1,000,000 lives annually worldwide.

A 2004 study commissioned by environmental groups, but contested by the

US EPA, concluded that coal burning costs 24,000 lives a year in the

United States. More recently, an academic study estimated that the premature deaths from coal related air pollution was about 52,000.

When compared to electricity produced from natural gas via hydraulic

fracturing, coal electricity is 10–100 times more toxic, largely due to

the amount of particulate matter emitted during combustion. When coal is compared to solar photovoltaic generation, the latter could save 51,999 American lives per year if solar were to replace coal generation in the U.S.

Due to the decline of jobs related to coal mining a study found that

approximately one American suffers a premature death from coal pollution for every job remaining in coal mining.

In addition, the list of historical coal mining disasters

is a long one, although work related coal deaths has declined

substantially as safety measures have been enacted and underground

mining has given up market share to surface mining. Underground mining

hazards include suffocation, gas poisoning, roof collapse and gas

explosions. Open cut hazards are principally mine wall failures and

vehicle collisions. In the United States, an average of 26 coal miners

per year died in the decade 2005–2014.

Land use management

Impact to land and surroundings

Strip mining severely alters the landscape, which reduces the value of the natural environment in the surrounding land.

The land surface is dedicated to mining activities until it can be

reshaped and reclaimed. If mining is allowed, resident human populations

must be resettled off the mine site; economic activities, such as

agriculture or hunting and gathering food and medicinal plants are

interrupted. What becomes of the land surface after mining is determined

by the manner in which the mining is conducted. Usually reclamation of

disturbed lands to a land use condition is not equal to the original

use. Existing land uses (such as livestock grazing, crop and timber

production) are temporarily eliminated in mining areas. High-value,

intensive-land-use areas like urban and transportation systems are not

usually affected by mining operations. If mineral values are sufficient,

these improvements may be removed to an adjacent area.

Strip mining eliminates existing vegetation, destroys the genetic

soil profile, displaces or destroys wildlife and habitat, alters

current land uses, and to some extent permanently changes the general

topography of the area mined.

Adverse impacts on geological features of human interest may occur in a

coal strip mine. Geomorphic and geophysical features and outstanding

scenic resources may be sacrificed by indiscriminate mining.

Paleontological, cultural, and other historic values may be endangered

due to the disruptive activities of blasting, ripping, and excavating

coal. Stripping of overburden eliminates and destroys archeological and

historic features, unless they are removed beforehand.

The removal of vegetative cover and activities associated with

the construction of haul roads, stockpiling of topsoil, displacement of overburden

and hauling of soil and coal increase the quantity of dust around

mining operations. Dust degrades air quality in the immediate area, has

an adverse impact on vegetative life, and constitutes health and safety

hazards for mine workers and nearby residents.

Surface mining disrupts virtually all aesthetic elements of the

landscape. Alteration of land forms often imposes unfamiliar and

discontinuous configurations. New linear patterns appear as material is

extracted and waste piles are developed. Different colors and textures

are exposed as vegetative cover is removed and overburden dumped to the

side. Dust, vibration, and diesel exhaust odors are created (affecting

sight, sound, and smell). Residents of local communities often find such

impacts disturbing or unpleasant. In case of mountaintop removal,

tops are removed from mountains or hills to expose thick coal seams

underneath. The soil and rock removed is deposited in nearby valleys,

hollows and depressions, resulting in blocked (and contaminated)

waterways.

Removal of soil and rock overburden covering the coal resource

may cause burial and loss of topsoil, exposes parent material, and

creates large infertile wastelands. Soil disturbance and associated

compaction result in conditions conducive to erosion. Soil removal from

the area to be surface-mined alters or destroys many natural soil

characteristics, and reduces its biodiversity and productivity for

agriculture. Soil structure may be disturbed by pulverization or

aggregate breakdown.

Mine collapses (or mine subsidences) have the potential to

produce major effects above ground, which are especially devastating in

developed areas. German underground coal-mining (especially in North Rhine-Westphalia)

has damaged thousands of houses, and the coal-mining industries have

set aside large sums in funding for future subsidence damages as part of

their insurance and state-subsidy schemes. In a particularly

spectacular case in the German Saar region (another historical coal-mining area), a suspected mine collapse in 2008 created an earthquake measuring 4.0 on the Richter magnitude scale,

causing some damage to houses. Previously, smaller earthquakes had

become increasingly common and coal mining was temporarily suspended in

the area.

In response to negative land effects of coal mining and the

abundance of abandoned mines in the US the federal government enacted

the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, which requires reclamation plans for future coal mining sites. These plans must be approved by federal or state authorities before mining begins.

Water management

Surface

mining may impair groundwater in numerous ways: by drainage of usable

water from shallow aquifers; lowering of water levels in adjacent areas

and changes in flow direction within aquifers; contamination of usable

aquifers below mining operations due to infiltration (percolation) of

poor-quality mine water; and increased infiltration of precipitation on spoil piles.

Where coal or carbonaceous shale is present, increased infiltration may

result in: increased runoff of poor-quality water and erosion from

spoil piles, recharge of poor-quality water to shallow groundwater

aquifers and poor-quality water flow to nearby streams.

The contamination of both groundwater and nearby streams may be

for long periods of time. Deterioration of stream quality results from acid mine drainage,

toxic trace elements, high content of dissolved solids in mine drainage

water, and increased sediment loads discharged to streams. When coal

surfaces are exposed, pyrite

comes in contact with water and air and forms sulfuric acid. As water

drains from the mine, the acid moves into the waterways; as long as rain

falls on the mine tailings the sulfuric-acid production continues, whether the mine is still operating or not.

Also waste piles and coal storage piles can yield sediment to streams.

Surface waters may be rendered unfit for agriculture, human consumption,

bathing, or other household uses.

To anticipate these problems, water is monitored at coal mines.

The five principal technologies used to control water flow at mine

sites are: diversion systems, containment ponds, groundwater pumping

systems, subsurface drainage systems, and subsurface barriers.

River water pollution

Coal-fired boilers / power plants when using coal or lignite rich in limestone produces ash containing calcium oxide (CaO). CaO readily dissolves in water to form slaked lime / Ca(OH)2 and carried by rainwater to rivers/irrigation water from the ash dump areas. Lime softening process precipitates Ca and Mg ions / removes temporary hardness in the water and also converts sodium bicarbonates in river water into sodium carbonate. Sodium carbonate (washing soda) further reacts with the remaining Ca and Mg in the water to remove / precipitate the total hardness.

Also, water-soluble sodium salts present in the ash enhance the sodium

content in water further. Thus river water is converted into soft water by eliminating Ca and Mg ions and enhancing Na ions by coal-fired boilers. Soft water application in irrigation (surface or ground water) converts the fertile soils into alkaline sodic soils. River water alkalinity and sodicity

due to the accumulation of salts in the remaining water after meeting

various transpiration and evaporation losses, become acute when many

coal-fired boilers and power stations are installed in a river basin.

River water sodicity affects downstream cultivated river basins located

in China, India, Egypt, Pakistan, west Asia, Australia, western US,

etc.

Waste management

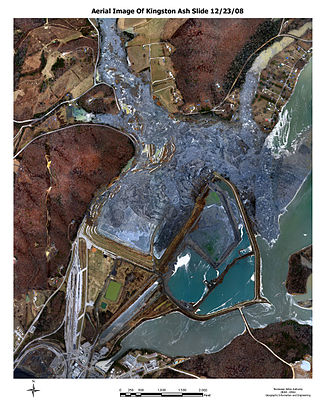

Aerial photograph of Kingston Fossil Plant coal fly ash slurry spill site taken the day after the event (23 December 2008)

The burning of coal leaves substantial quantities of fly ash, which

is usually stored in impoundment ponds. In the low-coal-content areas

waste forms spoil tip.

The U.S. EPA classified the 44 sites as potential hazards to

communities (which means the waste sites could cause death and

significant property damage if an event such as a storm, a terrorist

attack or a structural failure caused a spill). The U.S. EPA estimated

that about 300 dry landfills and wet storage ponds are used around the

country to store ash from coal-fired power plants. The storage

facilities hold the noncombustible ingredients of coal and the ash

trapped by equipment designed to reduce air pollution.

Wildlife

Surface

mining of coal causes direct and indirect damage to wildlife. The

impact on wildlife stems primarily from disturbing, removing and

redistributing the land surface. Some impacts are short-term and

confined to the mine site however others have far-reaching, long-term

effects.

The most direct effect on wildlife is destruction or displacement

of species in areas of excavation and spoil piling. Pit and spoil areas

are not capable of providing food and cover for most species of

wildlife. Mobile wildlife species like game animals, birds, and

predators leave these areas. More sedentary animals like invertebrates,

reptiles, burrowing rodents, and small mammals may be destroyed. The

community of microorganisms and nutrient-cycling processes are upset by

movement, storage, and redistribution of soil.

Degradation of aquatic habitats is a major impact by surface

mining and may be apparent many miles from a mining site. Sediment

contamination of surface water is common with surface mining. Sediment

yields may increase a thousand times their former level as a result of

strip mining.

The effects of sediment on aquatic wildlife vary with the species

and the amount of contamination. High sediment levels can kill fish

directly, bury spawning beds, reduce light transmission, alter

temperature gradients, fill in pools, spread streamflows over wider,

shallower areas, and reduce the production of aquatic organisms used as

food by other species. These changes destroy the habitat of valued

species and may enhance habitat for less-desirable species. Existing

conditions are already marginal for some freshwater fish in the United

States, and the sedimentation of their habitat may result in their

extinction. The heaviest sediment pollution of drainage normally comes

within 5 to 25 years after mining. In some areas, unvegetated spoil

piles continue to erode even 50 to 65 years after mining.

The presence of acid-forming materials exposed as a result of

surface mining can affect wildlife by eliminating habitat and by causing

direct destruction of some species. Lesser concentrations can suppress

productivity, growth rate and reproduction of many aquatic species.

Acids, dilute concentrations of heavy metals, and high alkalinity can

cause severe damage to wildlife in some areas. The duration of

acidic-waste pollution can be long; estimates of the time required to

leach exposed acidic materials in the Eastern United States range from

800 to 3,000 years.

Air pollution

Air emissions

| “ | In northern China, air pollution from the burning of fossil fuels, principally coal, is causing people to die on average 5.5 years sooner than they otherwise might. | ” |

| — Tim Flannery, Atmosphere of Hope, 2015. | ||

Coal and coal waste products (including fly ash, bottom ash and boiler slag) release approximately 20 toxic-release chemicals, including arsenic, lead, mercury, nickel, vanadium, beryllium, cadmium, barium, chromium, copper, molybdenum, zinc, selenium and radium,

which are dangerous if released into the environment. While these

substances are trace impurities, enough coal is burned that significant

amounts of these substances are released.

The Mpumalanga highveld in South Africa is the most polluted area in the world due to the mining industry and coal plant power stations and the lowveld near the famous Kruger Park is under threat of new mine projects as well.

During combustion, the reaction between coal and the air produces oxides of carbon, including carbon dioxide (CO2, an important greenhouse gas), oxides of sulfur (mainly sulfur dioxide, SO2), and various oxides of nitrogen (NOx). Because of the hydrogenous and nitrogenous components of coal, hydrides and nitrides of carbon and sulfur are also produced during the combustion of coal in air. These include hydrogen cyanide (HCN), sulfur nitrate (SNO3) and other toxic substances.

SO2 and nitrogen oxide

react in the atmosphere to form fine particles and ground-level ozone

and are transported long distances, making it difficult for other states

to achieve healthy levels of pollution control.

The wet cooling towers used in coal-fired power stations, etc. emit drift and fog which are also an environmental concern. The drift contains Respirable suspended particulate matter. In case of cooling towers with sea water makeup, sodium salts are deposited on nearby lands which would convert the land into alkali soil, reducing the fertility of vegetative lands and also cause corrosion of nearby structures.

Fires sometimes occur in coal beds underground. When coal beds

are exposed, the fire risk is increased. Weathered coal can also

increase ground temperatures if it is left on the surface. Almost all

fires in solid coal are ignited by surface fires caused by people or

lightning. Spontaneous combustion is caused when coal oxidizes and

airflow is insufficient to dissipate heat; this more commonly occurs in

stockpiles and waste piles, rarely in bedded coal underground. Where

coal fires occur, there is attendant air pollution from emission of

smoke and noxious fumes into the atmosphere. Coal seam fires may burn

underground for decades, threatening destruction of forests, homes,

roadways and other valuable infrastructure. The best-known coal-seam

fire may be the one which led to the permanent evacuation of Centralia, Pennsylvania, United States.

Approximately 75 Tg/S per year of Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) is released from burning coal. After release, the Sulfur Dioxide is oxidized to gaseous H2SO2

which scatters solar radiation, hence their increase in the atmosphere

exerts a cooling effect on climate that masks some of the warming caused

by increased greenhouse gases. Release of SO2 also contributes to the widespread acidification of ecosystems.

Mercury emissions

"Power plants... are responsible for half of... the mercury emissions in the United States."

In New York State winds deposit mercury from the coal-fired power plants of the Midwest, contaminating the waters of the Catskill Mountains. Mercury is concentrated up the food chain, as it is converted into methylmercury, a toxic compound which harms both wildlife and people who consume freshwater fish. The mercury is consumed by worms, which are eaten by fish, which are eaten by birds (including bald eagles). As of 2008, mercury levels in bald eagles in the Catskills had reached new heights.

"People are exposed to methylmercury almost entirely by eating

contaminated fish and wildlife that are at the top of aquatic food

chains." Ocean fish account for the majority of human exposure to methylmercury; the full range of sources of methylmercury in ocean fish is not well understood.

In February 2012, the U.S. EPA issued Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS), which require all coal plants to substantially reduce mercury emissions.

"Today [2011], more than half of all coal-fired power plants already

deploy pollution control technologies that will help them meet these

achievable standards. Once final, these standards will level the playing

field by ensuring the remaining plants – about 40 percent of all

coal-fired power plants – take similar steps to decrease dangerous

pollutants."

Annual excess mortality and morbidity

In 2008 the World Health Organization

(WHO) and other organizations calculated that coal particulates

pollution cause approximately one million deaths annually across the

world, which is approximately one third of all premature deaths related to all air pollution sources, for example in Istanbul by lung diseases and cancer.

Pollutants emitted by burning coal include fine particulates (PM2.5) and ground level ozone.

Every year, the burning of coal without the use of available pollution

control technology causes thousands of preventable deaths in the United

States. A study commissioned by the Maryland nurses association in

2006 found that emissions from just six of Maryland's coal-burning

plants caused 700 deaths per year nationwide, including 100 in Maryland.

Since installation of pollution abatement equipment on one of these

six, the Brandon Shores plant, now "produces 90 percent less nitrogen

oxide, an ingredient of smog; 95 percent less sulfur, which causes acid

rain; and vastly lower fractions of other pollutants."

Economic costs

A 2001 EU-funded study known as ExternE, or Externalities

of Energy, over the decade from 1995 to 2005 found that the cost of

producing electricity from coal would double over its present value, if

external costs were taken into account. These external costs include

damage to the environment and to human health from airborne particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, chromium VI and arsenic emissions produced by coal. It was estimated that external, downstream, fossil fuel costs amount up to 1–2% of the EU's entire Gross Domestic Product (GDP),

with coal being the main fossil fuel accountable, and this was before

the external cost of global warming from these sources was even

included.

The study found that environmental and health costs of coal alone were

€0.06/kWh, or 6 cents/kWh, with the energy sources of the lowest

external costs being nuclear power €0.0019/kWh, and wind power at €0.0009/kWh.

High rates of motherboard

failures in China and India appear to be due to "sulfurous air

pollution produced by coal that’s burned to generate electricity. It

corrodes the copper circuitry," according to Intel researchers.

Greenhouse gas emissions

The combustion of coal is the largest contributor to the human-made increase of CO2 in the atmosphere. Electric generation using coal burning produces approximately twice the greenhouse gasses per kilowatt compared to generation using natural gas.

Coal mining releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Methane is

the naturally occurring product of the decay of organic matter as coal

deposits are formed with increasing depths of burial, rising

temperatures, and rising pressure over geological time. A portion of the

methane produced is absorbed by the coal and later released from the

coal seam (and surrounding disturbed strata) during the mining process. Methane accounts for 10.5 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions created through human activity. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, methane has a global warming

potential 21 times greater than that of carbon dioxide over a 100-year

timeline. The process of mining can release pockets of methane. These

gases may pose a threat to coal miners, as well as a source of air

pollution. This is due to the relaxation of pressure and fracturing of

the strata during mining activity, which gives rise to safety concerns

for the coal miners if not managed properly. The buildup of pressure in

the strata can lead to explosions during (or after) the mining process

if prevention methods, such as "methane draining", are not taken.

In 2008 James E. Hansen and Pushker Kharecha published a peer-reviewed scientific study analyzing the effect of a coal phase-out on atmospheric CO2 levels. Their baseline mitigation scenario was a phaseout of global coal emissions by 2050. Under the Business as Usual scenario, atmospheric CO2 peaks at 563 parts per million (ppm) in the year 2100. Under the four coal phase-out scenarios, atmospheric CO2 peaks at 422–446 ppm between 2045 and 2060 and declines thereafter.

Radiation exposure

Coal also contains low levels of uranium, thorium, and other naturally occurring radioactive isotopes which, if released into the environment, may lead to radioactive contamination. Coal plants emit radiation in the form of radioactive fly ash, which is inhaled and ingested by neighbours, and incorporated into crops. A 1978 paper from Oak Ridge National Laboratory estimated that coal-fired power plants of that time may contribute a whole-body committed dose of 19 µSv/a to their immediate neighbours in a 500 m radius. The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation's

1988 report estimated the committed dose 1 km away to be 20 µSv/a for

older plants or 1 µSv/a for newer plants with improved fly ash capture,

but was unable to confirm these numbers by test.

Excluding contained waste and unintentional releases from nuclear

plants, coal-plants carry more radioactive wastes into the environment

than nuclear plants per unit of produced energy. Plant-emitted radiation

carried by coal-derived fly ash delivers 100 times more radiation to

the surrounding environment than does the normal operation of a

similarly productive nuclear plant.

This comparison does not consider the rest of the fuel cycle, i.e.,

coal and uranium mining and refining and waste disposal. The operation

of a 1000-MWe coal-fired power plant results in a nuclear radiation dose

of 490 person-rem/year, compared to 136 person-rem/year, for an

equivalent nuclear power plant including uranium mining, reactor

operation and waste disposal.

Dangers to miners

Historically, coal mining has been a very dangerous activity, and the list of historical coal mining disasters

is long. The principal hazards are mine wall failures and vehicle

collisions; underground mining hazards include suffocation, gas

poisoning, roof collapse and gas explosions. Chronic lung diseases, such as pneumoconiosis (black lung) were once common in miners, leading to reduced life expectancy.

In some mining countries black lung is still common, with 4,000 new

cases of black lung every year in the US (4 percent of workers annually)

and 10,000 new cases every year in China (0.2 percent of workers). Rates may be higher than reported in some regions.

In the United States, an average of 23 coal miners per year died in the decade 2007–2016. Recent U.S. coal-mining disasters include the Sago Mine disaster of January 2006. In 2007, a mine accident in Utah's Crandall Canyon Mine killed nine miners, with six entombed. The Upper Big Branch Mine disaster in West Virginia killed 29 miners in April 2010.

However, in lesser developed countries and some developing

countries, many miners continue to die annually, either through direct

accidents in coal mines or through adverse health consequences from

working under poor conditions. China,

in particular, has the highest number of coal mining related deaths in

the world, with official statistics claiming that 6,027 deaths in 2004. To compare, 28 deaths were reported in the US in the same year. Coal production in China is twice that in the US,

while the number of coal miners is around 50 times that of the US,

making deaths in coal mines in China 4 times as common per worker (108

times as common per unit output) as in the US.

The Farmington coal mine disaster kills 78. West Virginia, US, 1968.

Build-ups of a hazardous gas are known as damps:

- Black damp: a miture of carbon dioxide and nitrogen in a mine can cause suffocation. The anoxic condition results of depletion of oxygen in enclosed spaces, e.g. by corrosion.

- After damp: similar to black damp, after damp consists of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and nitrogen and forms after a mine explosion.

- Fire damp: consists of mostly methane, a highly flammable gas that explodes between 5% and 15% – at 25% it causes asphyxiation.

- Stink damp: so named for the rotten egg smell of the hydrogen sulphide gas, stink damp can explode and is also very toxic.

- White damp: air containing carbon monoxide which is toxic, even at low concentrations

Firedamp explosions can trigger the much more dangerous coal dust

explosions, which can engulf an entire pit. Most of these risks can be

greatly reduced in modern mines, and multiple fatality incidents are now

rare in some parts of the developed world. Modern mining in the US

results in approximately 30 deaths per year due to mine accidents.