| Body mass index (BMI) | |

|---|---|

| Medical diagnostics | |

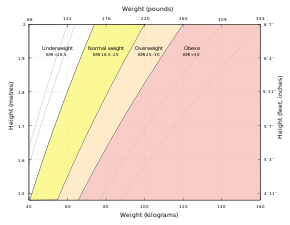

A

graph of body mass index as a function of body mass and body height.

The dashed lines represent subdivisions within a major class.

| |

| Synonyms | Quetelet index |

| MeSH | D015992 |

| MedlinePlus | 007196 |

| LOINC | 39156-5 |

Body mass index (BMI) is a value derived from the mass (weight) and height of a person. The BMI is defined as the body mass divided by the square of the body height, and is universally expressed in units of kg/m2, resulting from mass in kilograms and height in metres.

The BMI may be determined using a table or chart which displays BMI as a function of mass and height using contour lines or colours for different BMI categories, and which may use other units of measurement (converted to metric units for the calculation).

The BMI is a convenient rule of thumb used to broadly categorize a person as underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese based on tissue mass (muscle, fat, and bone) and height. That categorization is the subject of some debate about where on the BMI scale the dividing lines between categories should be placed. Commonly accepted BMI ranges are underweight: under 18.5 kg/m2, normal weight: 18.5 to 25, overweight: 25 to 30, obese: over 30.

BMIs under 20.0 and over 25.0 have been associated with higher all-causes mortality, with the risk increasing with distance from the 20.0–25.0 range.

History

Obesity and BMI

Adolphe Quetelet,

a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician, and sociologist,

devised the basis of the BMI between 1830 and 1850 as he developed what

he called "social physics". The modern term "body mass index" (BMI) for the ratio of human body weight to squared height was coined in a paper published in the July 1972 edition of the Journal of Chronic Diseases by Ancel Keys

and others. In this paper, Keys argued that what he termed the BMI was

"...if not fully satisfactory, at least as good as any other relative

weight index as an indicator of relative obesity".

The interest in an index that measures body fat came with observed increasing obesity in prosperous Western societies. Keys explicitly judged BMI as appropriate for population

studies and inappropriate for individual evaluation. Nevertheless, due

to its simplicity, it has come to be widely used for preliminary

diagnoses. Additional metrics, such as waist circumference, can be more useful.

The BMI is universally expressed in kg/m2, resulting from mass in kilograms and height in metres. If pounds and inches are used, a conversion factor of 703 (kg/m2)/(lb/in2) must be applied. When the term BMI is used informally, the units are usually omitted.

BMI provides a simple numeric measure of a person's thickness or thinness,

allowing health professionals to discuss weight problems more

objectively with their patients. BMI was designed to be used as a simple

means of classifying average sedentary (physically inactive)

populations, with an average body composition.

For such individuals, the value recommendations as of 2014 are as follows: a BMI from 18.5 up to 25 kg/m2 may indicate optimal weight, a BMI lower than 18.5 suggests the person is underweight, a number from 25 up to 30 may indicate the person is overweight, and a number from 30 upwards suggests the person is obese.

Lean male athletes often have a high muscle-to-fat ratio and therefore a

BMI that is misleadingly high relative to their body-fat percentage.

Scalability

BMI

is proportional to the mass and inversely proportional to the square of

the height. So, if all body dimensions double, and mass scales

naturally with the cube of the height, then BMI doubles instead of

remaining the same. This results in taller people having a reported BMI

that is uncharacteristically high, compared to their actual body fat

levels. In comparison, the Ponderal index is based on the natural scaling of mass with the third power of the height.

However, many taller people are not just "scaled up" short people

but tend to have narrower frames in proportion to their height. Carl

Lavie has written that, "The B.M.I. tables are excellent for identifying

obesity and body fat in large populations, but they are far less

reliable for determining fatness in individuals."

Categories

A

frequent use of the BMI is to assess how far an individual's body

weight departs from what is normal or desirable for a person's height.

The weight excess or deficiency may, in part, be accounted for by body

fat (adipose tissue) although other factors such as muscularity also affect BMI significantly (see discussion below and overweight).

The WHO regards a BMI of less than 18.5 as underweight and may indicate malnutrition, an eating disorder, or other health problems, while a BMI equal to or greater than 25 is considered overweight and above 30 is considered obese. These ranges of BMI values are valid only as statistical categories.

| Category | BMI (kg/m2) | BMI Prime | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

from | to | from | to |

| Very severely underweight | 15 | 0.60 | ||

| Severely underweight | 15 | 16 | 0.60 | 0.64 |

| Underweight | 16 | 18.5 | 0.64 | 0.74 |

| Normal (healthy weight) | 18.5 | 25 | 0.74 | 1.0 |

| Overweight | 25 | 30 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Obese Class I (Moderately obese) | 30 | 35 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| Obese Class II (Severely obese) | 35 | 40 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Obese Class III (Very severely obese) | 40 | 45 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Obese Class IV (Morbidly obese) | 45 | 50 | 1.8 | 2 |

| Obese Class V (Super obese) | 50 | 60 | 2 | 2.4 |

| Obese Class VI (Hyper obese) | 60 |

|

2.4 |

|

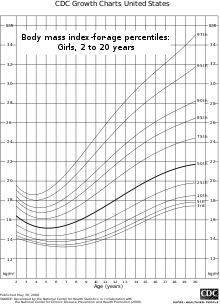

Children (aged 2 to 20)

BMI for age percentiles for boys 2 to 20 years of age.

BMI for age percentiles for girls 2 to 20 years of age.

BMI is used differently for children. It is calculated in the same

way as for adults, but then compared to typical values for other

children of the same age. Instead of comparison against fixed thresholds

for underweight and overweight, the BMI is compared against the percentiles for children of the same sex and age.

A BMI that is less than the 5th percentile is considered

underweight and above the 95th percentile is considered obese. Children

with a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile are considered to be

overweight.

Recent studies in Britain have indicated that females between the

ages 12 and 16 have a higher BMI than males of the same age by 1.0 kg/m2 on average.

International variations

These

recommended distinctions along the linear scale may vary from time to

time and country to country, making global, longitudinal surveys

problematic. People from different ethnic groups, populations, and

descent have different associations between BMI, percentage of body fat,

and health risks, with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease at BMIs lower than the WHO cut-off point for overweight, 25 kg/m2,

although the cut-off for observed risk varies among different

populations. The cut-off for observed risk varies based on populations

and subpopulations both in Europe and Asia.

Hong Kong

The Hospital Authority of Hong Kong recommends the use of the following BMI ranges:

| Category | BMI (kg/m2) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

from | to |

| Underweight | 18.5 | |

| Normal Range | 18.5 | 23 |

| Overweight—At Risk | 23 | 25 |

| Overweight—Moderately Obese | 25 | 30 |

| Overweight—Severely Obese | 30 |

|

Japan

Japan Society for the Study of Obesity (2000):

| Category | BMI (kg/m2) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

from | to |

| Low | 18.5 | |

| Normal | 18.5 | 25 |

| Obese (Level 1) | 25 | 30 |

| Obese (Level 2) | 30 | 35 |

| Obese (Level 3) | 35 | 40 |

| Obese (Level 4) | 40 |

|

Singapore

In

Singapore, the BMI cut-off figures were revised in 2005, motivated by

studies showing that many Asian populations, including Singaporeans,

have higher proportion of body fat and increased risk for cardiovascular

diseases and diabetes mellitus,

compared with general BMI recommendations in other countries. The BMI

cut-offs are presented with an emphasis on health risk rather than

weight.

| Health Risk | BMI (kg/m2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of developing problems such as nutritional deficiency and osteoporosis | under 18.5 | |

| Low Risk (healthy range) | 18.5 to 23 | |

| Moderate risk of developing heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes | 23 to 27.5 | |

| High risk of developing heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes | over 27.5 | |

United States

In 1998, the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention brought U.S. definitions in line with World Health Organization

guidelines, lowering the normal/overweight cut-off from BMI 27.8 to BMI

25. This had the effect of redefining approximately 29 million

Americans, previously healthy, to overweight.

This can partially explain the increase in the overweight diagnosis in the past 20 years, and the increase in sales of weight loss products during the same time. WHO

also recommends lowering the normal/overweight threshold for South East

Asian body types to around BMI 23, and expects further revisions to

emerge from clinical studies of different body types.

The U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1994

showed that 59.8% of American men and 51.2% of women had BMIs over 25.

Morbid obesity—a BMI of 40 or more—was found in 2% of the men and 4% of

the women. A survey in 2007 showed 63% of Americans are overweight or

obese, with 26% in the obese category (a BMI of 30 or more). As of 2014,

37.7% of adults in the United States were obese, categorized as 35.0%

of men and 40.4% of women; class 3 obesity (BMI over 40) values were

7.7% for men and 9.9% for women.

| Age | Percentile | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th | 10th | 15th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 85th | 90th | 95th | |

| Men BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| 20 years and over (total) | 20.7 | 22.2 | 23.0 | 24.6 | 27.7 | 31.6 | 34.0 | 36.1 | 39.8 |

| 20–29 years | 19.3 | 20.5 | 21.2 | 22.5 | 25.5 | 30.5 | 33.1 | 35.1 | 39.2 |

| 30–39 years | 21.1 | 22.4 | 23.3 | 24.8 | 27.5 | 31.9 | 35.1 | 36.5 | 39.3 |

| 40–49 years | 21.9 | 23.4 | 24.3 | 25.7 | 28.5 | 31.9 | 34.4 | 36.5 | 40.0 |

| 50–59 years | 21.6 | 22.7 | 23.6 | 25.4 | 28.3 | 32.0 | 34.0 | 35.2 | 40.3 |

| 60–69 years | 21.6 | 22.7 | 23.6 | 25.3 | 28.0 | 32.4 | 35.3 | 36.9 | 41.2 |

| 70–79 years | 21.5 | 23.2 | 23.9 | 25.4 | 27.8 | 30.9 | 33.1 | 34.9 | 38.9 |

| 80 years and over | 20.0 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 24.1 | 26.3 | 29.0 | 31.1 | 32.3 | 33.8 |

| Age | Women BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||

| 20 years and over (total) | 19.6 | 21.0 | 22.0 | 23.6 | 27.7 | 33.2 | 36.5 | 39.3 | 43.3 |

| 20–29 years | 18.6 | 19.8 | 20.7 | 21.9 | 25.6 | 31.8 | 36.0 | 38.9 | 42.0 |

| 30–39 years | 19.8 | 21.1 | 22.0 | 23.3 | 27.6 | 33.1 | 36.6 | 40.0 | 44.7 |

| 40–49 years | 20.0 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 23.7 | 28.1 | 33.4 | 37.0 | 39.6 | 44.5 |

| 50–59 years | 19.9 | 21.5 | 22.2 | 24.5 | 28.6 | 34.4 | 38.3 | 40.7 | 45.2 |

| 60–69 years | 20.0 | 21.7 | 23.0 | 24.5 | 28.9 | 33.4 | 36.1 | 38.7 | 41.8 |

| 70–79 years | 20.5 | 22.1 | 22.9 | 24.6 | 28.3 | 33.4 | 36.5 | 39.1 | 42.9 |

| 80 years and over | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.3 | 23.3 | 26.1 | 29.7 | 30.9 | 32.8 | 35.2 |

Consequences of elevated level in adults

The BMI ranges are based on the relationship between body weight and disease and death.[26] Overweight and obese individuals are at an increased risk for the following diseases:[27]

- Coronary artery disease

- Dyslipidemia

- Type 2 diabetes

- Gallbladder disease

- Hypertension

- Osteoarthritis

- Sleep apnea

- Stroke

- At least 10 cancers, including endometrial, breast, and colon cancer.

- Epidural lipomatosis

Among people who have never smoked, overweight/obesity is associated

with 51% increase in mortality compared with people who have always been

a normal weight.

Applications

Public health

The

BMI is generally used as a means of correlation between groups related

by general mass and can serve as a vague means of estimating adiposity.

The duality of the BMI is that, while it is easy to use as a general

calculation, it is limited as to how accurate and pertinent the data

obtained from it can be. Generally, the index is suitable for

recognizing trends within sedentary or overweight individuals because

there is a smaller margin of error. The BMI has been used by the WHO as the standard for recording obesity statistics since the early 1980s.

This general correlation is particularly useful for consensus

data regarding obesity or various other conditions because it can be

used to build a semi-accurate representation from which a solution can

be stipulated, or the RDA

for a group can be calculated. Similarly, this is becoming more and

more pertinent to the growth of children, due to the fact that the

majority of children are sedentary.

Cross-sectional studies indicated that sedentary people can decrease BMI

by becoming more physically active. Smaller effects are seen in

prospective cohort studies which lend to support active mobility as a

means to prevent a further increase in BMI.

Clinical practice

BMI categories are generally regarded as a satisfactory tool for measuring whether sedentary individuals are underweight, overweight, or obese with various exceptions, such as: athletes, children, the elderly, and the infirm.

Also, the growth of a child is documented against a BMI-measured growth

chart. Obesity trends can then be calculated from the difference

between the child's BMI and the BMI on the chart.

In the United States, BMI is also used as a measure of underweight,

owing to advocacy on behalf of those with eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

Legislation

In France, Italy, and Spain, legislation has been introduced banning the usage of fashion show models having a BMI below 18. In Israel, a BMI below 18.5 is banned. This is done to fight anorexia among models and people interested in fashion.

Limitations

The medical establishment and statistical community have both highlighted the limitations of BMI.

Scaling

The exponent in the denominator of the formula for BMI is arbitrary. The BMI depends upon weight and the square of height. Since mass increases to the third power of linear dimensions, taller individuals with exactly the same body shape and relative composition have a larger BMI.

According to mathematician Nick Trefethen,

"BMI divides the weight by too large a number for short people and too

small a number for tall people. So short people are misled into thinking

that they are thinner than they are, and tall people are misled into

thinking they are fatter."

For US adults, exponent estimates range from 1.92 to 1.96 for males and from 1.45 to 1.95 for females.

Physical characteristics

The

BMI overestimates roughly 10% for a large (or tall) frame and

underestimates roughly 10% for a smaller frame (short stature). In other

words, persons with small frames would be carrying more fat than

optimal, but their BMI indicates that they are normal. Conversely, large framed (or tall) individuals may be quite healthy, with a fairly low body fat percentage, but be classified as overweight by BMI.

For example, a height/weight chart may say the ideal weight (BMI

21.5) for a man 5 ft 10 in (178 cm) is 150 pounds (68 kg). But if that

man has a slender build (small frame), he may be overweight at 150

pounds (68 kg) and should reduce by 10%, to roughly 135 pounds (61 kg)

(BMI 19.4). In the reverse, the man with a larger frame and more solid

build should increase by 10%, to roughly 165 pounds (75 kg) (BMI 23.7).

If one teeters on the edge of small/medium or medium/large, common sense

should be used in calculating one's ideal weight. However, falling into

one's ideal weight range for height and build is still not as accurate

in determining health risk factors as waist-to-height ratio and actual body fat percentage.

Accurate frame size calculators use several measurements (wrist

circumference, elbow width, neck circumference and others) to determine

what category an individual falls into for a given height.

The BMI also fails to take into account loss of height through aging.

In this situation, BMI will increase without any corresponding increase

in weight.

A new formula, that accounts for the distortions of BMI at high

and low heights, has been suggested: BMI = 1.3*weight(kg)/height(m)^2.5.

Muscle versus fat

Assumptions about the distribution between muscle mass and fat mass are inexact. BMI generally overestimates adiposity on those with more lean body mass (e.g., athletes) and underestimates excess adiposity on those with less lean body mass.

A study in June 2008 by Romero-Corral et al. examined 13,601 subjects from the United States' third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

(NHANES III) and found that BMI-defined obesity (BMI > 30) was

present in 21% of men and 31% of women. Body fat-defined obesity was

found in 50% of men and 62% of women. While BMI-defined obesity showed

high specificity (95% for men and 99% for women), BMI showed poor sensitivity

(36% for men and 49% for women). In other words, BMI is better at

determining a person is not obese than it is at determining a person is

obese. Despite this undercounting of obesity by BMI, BMI values in the

intermediate BMI range of 20–30 were found to be associated with a wide

range of body fat percentages. For men with a BMI of 25, about 20% have a

body fat percentage below 20% and about 10% have body fat percentage

above 30%.

BMI is particularly inaccurate for people who are very fit or athletic, as their high muscle mass can classify them in the overweight

category by BMI, even though their body fat percentages frequently fall

in the 10–15% category, which is below that of a more sedentary person

of average build who has a normal BMI number. For example, the BMI of bodybuilder and eight-time Mr. Olympia Ronnie Coleman was 41.8 at his peak physical condition, which would be considered morbidly obese.

Body composition for athletes is often better calculated using

measures of body fat, as determined by such techniques as skinfold

measurements or underwater weighing and the limitations of manual

measurement have also led to new, alternative methods to measure

obesity, such as the body volume index.

Variation in definitions of categories

It is not clear where on the BMI scale the threshold for overweight and obese

should be set. Because of this the standards have varied over the past

few decades. Between 1980 and 2000 the U.S. Dietary Guidelines have

defined overweight at a variety of levels ranging from a BMI of 24.9 to

27.1. In 1985 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference recommended that overweight BMI be set at a BMI of 27.8 for men and 27.3 for women.

In 1998 a NIH report concluded that a BMI over 25 is overweight and a BMI over 30 is obese. In the 1990s the World Health Organization

(WHO) decided that a BMI of 25 to 30 should be considered overweight

and a BMI over 30 is obese, the standards the NIH set. This became the

definitive guide for determining if someone is overweight.

The current WHO and NIH ranges of normal weights are

proved to be associated with decreased risks of some diseases such as

diabetes type II; however using the same range of BMI for men and women

is considered arbitrary, and makes the definition of underweight quite

unsuitable for men.

One study found that the vast majority of people labelled

'overweight' and 'obese' according to current definitions do not in fact

face any meaningful increased risk for early death. In a quantitative

analysis of a number of studies, involving more than 600,000 men and

women, the lowest mortality rates were found for people with BMIs

between 23 and 29; most of the 25–30 range considered 'overweight' was

not associated with higher risk.

Relationship to health

A study published by Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2005 showed that overweight people had a death rate similar to normal weight people as defined by BMI, while underweight and obese people had a higher death rate.

A study published by The Lancet in 2009 involving 900,000 adults showed that overweight and underweight people both had a mortality rate higher than normal weight people as defined by BMI. The optimal BMI was found to be in the range of 22.5–25.

High BMI is associated with type 2 diabetes only in persons with high serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase.

In an analysis of 40 studies involving 250,000 people, patients with coronary artery disease with normal BMIs were at higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease than people whose BMIs put them in the overweight range (BMI 25–29.9).

One study found that BMI had a good general correlation with body

fat percentage, and noted that obesity has overtaken smoking as the

world's number one cause of death. But it also notes that in the study

50% of men and 62% of women were obese according to body fat defined

obesity, while only 21% of men and 31% of women were obese according to

BMI, meaning that BMI was found to underestimate the number of obese

subjects.

A 2010 study that followed 11,000 subjects for up to eight years

concluded that BMI is not a good measure for the risk of heart attack,

stroke or death. A better measure was found to be the waist-to-height ratio. A 2011 study that followed 60,000 participants for up to 13 years found that waist–hip ratio was a better predictor of ischaemic heart disease mortality.

Alternatives

BMI prime

BMI prime, a modification of the BMI system, is the ratio of actual BMI to upper limit optimal BMI (currently defined at 25 kg/m2),

i.e., the actual BMI expressed as a proportion of upper limit optimal.

The ratio of actual body weight to body weight for upper limit optimal

BMI (25 kg/m2) is equal to BMI Prime. BMI Prime is a dimensionless number

independent of units. Individuals with BMI Prime less than 0.74 are

underweight; those with between 0.74 and 1.00 have optimal weight; and

those at 1.00 or greater are overweight. BMI Prime is useful clinically

because it shows by what ratio (e.g. 1.36) or percentage (e.g. 136%, or

36% above) a person deviates from the maximum optimal BMI.

For instance, a person with BMI 34 kg/m2 has a BMI

Prime of 34/25 = 1.36, and is 36% over their

upper mass limit. In South

East Asian and South Chinese populations (see § international variations),

BMI Prime should be calculated using an upper limit BMI of 23 in the

denominator instead of 25. BMI Prime allows easy comparison between

populations whose upper-limit optimal BMI values differ.

Waist circumference

Waist circumference is a good indicator of visceral fat, which poses more health risks than fat elsewhere. According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health

(NIH), waist circumference in excess of 102 centimetres (40 in) for men

and 88 centimetres (35 in) for (non-pregnant) women, is considered to

imply a high risk for type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia,

hypertension, and CVD. Waist circumference can be a better indicator of

obesity-related disease risk than BMI. For example, this is the case in

populations of Asian descent and older people.

94 centimetres (37 in) for men and 80 centimetres (31 in) for women has

been stated to pose "higher risk", with the NIH figures "even higher".

Waist-to-hip circumference ratio has also been used, but has been

found to be no better than waist circumference alone, and more

complicated to measure.

A related indicator is waist circumference divided by height. The

values indicating increased risk are: greater than 0.5 for people under

40 years of age, 0.5 to 0.6 for people aged 40–50, and greater than 0.6

for people over 50 years of age.

Surface-based body shape index

The Surface-based Body Shape Index (SBSI) is far more rigorous and is based upon four key measurements: the body surface area

(BSA), vertical trunk circumference (VTC), waist circumference (WC) and

height (H). Data on 11,808 subjects from the National Health and Human

Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1999–2004, showed that SBSI

outperformed BMI, waist circumference, and A Body Shape Index (ABSI), an alternative to BMI.

A simplified, dimensionless form of SBSI, known as SBSI*, has also been developed.

Modified body mass index

Within some medical contexts, such as familial amyloid polyneuropathy, serum albumin is factored in to produce a modified body mass index (mBMI). The mBMI can be obtained by multiplying the BMI by serum albumin, in grams per litre.