| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛstrəˈdaɪoʊl/ ES-trə-DY-ohl |

| IUPAC name

(8R,9S,13S,14S,17S)-13-Methyl-6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-decahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,17-diol

| |

| Other names

Oestradiol; E2; 17β-Estradiol; Estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol; 17β-Oestradiol

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.022 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C18H24O2 | |

| Molar mass | 272.38 g/mol |

| -186.6·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Pharmacology | |

| G03CA03 (WHO) | |

| License data | |

| Oral, sublingual, intranasal, topical/transdermal, vaginal, intramuscular or subcutaneous (as an ester), subdermal implant | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| Oral: <5 span=""> | |

| ~98%:• Albumin: 60% • SHBG: 38% • Free: 2% | |

| Liver (via hydroxylation, sulfation, glucuronidation) | |

| Oral: 13–20 hours Sublingual: 8–18 hours Topical (gel): 36.5 hours | |

| Urine: 54% Feces: 6% | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Estradiol (E2), also spelled oestradiol, is an estrogen steroid hormone and the major female sex hormone. It is involved in the regulation of the estrous and menstrual female reproductive cycles. Estradiol is responsible for the development of female secondary sexual characteristics such as the breasts, widening of the hips, and a female-associated pattern of fat distribution and is important in the development and maintenance of female reproductive tissues such as the mammary glands, uterus, and vagina during puberty, adulthood, and pregnancy. It also has important effects in many other tissues including bone, fat, skin, liver, and the brain. Though estradiol levels in males are much lower compared to those in females, estradiol has important roles in males as well. Apart from humans and other mammals, estradiol is also found in most vertebrates and crustaceans, insects, fish, and other animal species.

Estradiol is produced especially within the follicles of the ovaries, but also in other tissues including the testicles, the adrenal glands, fat, liver, the breasts, and the brain. Estradiol is produced in the body from cholesterol through a series of reactions and intermediates. The major pathway involves the formation of androstenedione, which is then converted by aromatase into estrone and is subsequently converted into estradiol. Alternatively, androstenedione can be converted into testosterone, which can then be converted into estradiol. Upon menopause in females, production of estrogens by the ovaries stops and estradiol levels decrease to very low levels.

In addition to its role as a natural hormone, estradiol is used as a medication, for instance in menopausal hormone therapy; for information on estradiol as a medication, see the estradiol (medication) article.

Biological function

Sexual development

The development of secondary sex characteristics in women is driven by estrogens, to be specific, estradiol. These changes are initiated at the time of puberty, most are enhanced during the reproductive years, and become less pronounced with declining estradiol support after menopause. Thus, estradiol produces breast development, and is responsible for changes in the body shape, affecting bones, joints, and fat deposition. In females, estradiol induces breast development, widening of the hips, a feminine fat distribution (with fat deposited particularly in the breasts, hips, thighs, and buttocks), and maturation of the vagina and vulva, whereas it mediates the pubertal growth spurt (indirectly via increased growth hormone secretion) and epiphyseal closure (thereby limiting final height) in both sexes.

Reproduction

Female reproductive system

In the female, estradiol acts as a growth hormone for tissue of the reproductive organs, supporting the lining of the vagina, the cervical glands, the endometrium, and the lining of the fallopian tubes. It enhances growth of the myometrium. Estradiol appears necessary to maintain oocytes in the ovary. During the menstrual cycle,

estradiol produced by the growing follicles triggers, via a positive

feedback system, the hypothalamic-pituitary events that lead to the luteinizing hormone surge, inducing ovulation. In the luteal phase, estradiol, in conjunction with progesterone, prepares the endometrium for implantation. During pregnancy, estradiol increases due to placental production. The effect of estradiol, together with estrone and estriol, in pregnancy

is less clear. They may promote uterine blood flow, myometrial growth,

stimulate breast growth and at term, promote cervical softening and

expression of myometrial oxytocin receptors.

In baboons, blocking of estrogen production leads to pregnancy loss,

suggesting estradiol has a role in the maintenance of pregnancy.

Research is investigating the role of estrogens in the process of

initiation of labor. Actions of estradiol are required before the exposure of progesterone in the luteal phase.

Male reproductive system

The effect of estradiol (and estrogens in general) upon male reproduction is complex. Estradiol is produced by action of aromatase mainly in the Leydig cells of the mammalian testis, but also by some germ cells and the Sertoli cells of immature mammals. It functions (in vitro) to prevent apoptosis of male sperm cells.

While some studies in the early 1990s claimed a connection between globally declining sperm counts and estrogen exposure in the environment, later studies found no such connection, nor evidence of a general decline in sperm counts.

Suppression of estradiol production in a subpopulation of subfertile men may improve the semen analysis.

Males with certain sex chromosome genetic conditions, such as Klinefelter's syndrome, will have a higher level of estradiol.

Skeletal system

Estradiol has a profound effect on bone. Individuals without it (or other estrogens) will become tall and eunuchoid, as epiphyseal

closure is delayed or may not take place. Low levels of estradiol may

also predict fractures, with the highest risk occurring particularly in

men with low total and high sex hormone binding globulin protein. Bone density, as well as joints, are also affected, resulting in early osteopenia and osteoporosis. Women past menopause experience an accelerated loss of bone mass due to a relative estrogen deficiency.

Skin health

The estrogen receptor, as well as the progesterone receptor, have been detected in the skin, including in keratinocytes and fibroblasts. At menopause and thereafter, decreased levels of female sex hormones result in atrophy, thinning, and increased wrinkling of the skin and a reduction in skin elasticity, firmness, and strength. These skin changes constitute an acceleration in skin aging and are the result of decreased collagen content, irregularities in the morphology of epidermal skin cells, decreased ground substance between skin fibers, and reduced capillaries and blood flow. The skin also becomes more dry during menopause, which is due to reduced skin hydration and surface lipids (sebum production).

Along with chronological aging and photoaging, estrogen deficiency in

menopause is one of the three main factors that predominantly influences

skin aging.

Hormone replacement therapy

consisting of systemic treatment with estrogen alone or in combination

with a progestogen, has well-documented and considerable beneficial

effects on the skin of postmenopausal women. These benefits include increased skin collagen content, skin thickness and elasticity, and skin hydration and surface lipids. Topical estrogen has been found to have similar beneficial effects on the skin.

In addition, a study has found that topical 2% progesterone cream

significantly increases skin elasticity and firmness and observably

decreases wrinkles in peri- and postmenopausal women. Skin hydration and surface lipids, on the other hand, did not significantly change with topical progesterone.

These findings suggest that progesterone, like estrogen, also has

beneficial effects on the skin, and may be independently protective

against skin aging.

Nervous system

Estrogens can be produced in the brain from steroid precursors. As antioxidants, they have been found to have neuroprotective function.

The positive and negative feedback loops of the menstrual cycle involve ovarian estradiol as the link to the hypothalamic-pituitary system to regulate gonadotropins.

Estrogen is considered to play a significant role in women's

mental health, with links suggested between the hormone level, mood and

well-being. Sudden drops or fluctuations in, or long periods of

sustained low levels of estrogen may be correlated with significant

mood-lowering. Clinical recovery from depression postpartum,

perimenopause, and postmenopause was shown to be effective after levels

of estrogen were stabilized and/or restored.

Recently, the volumes of sexually dimorphic brain structures in transgender women

were found to change and approximate typical female brain structures

when exposed to estrogen concomitantly with androgen deprivation over a

period of months, suggesting that estrogen and/or androgens have a significant part to play in sex differentiation of the brain, both prenatally and later in life.

There is also evidence the programming of adult male sexual

behavior in many vertebrates is largely dependent on estradiol produced

during prenatal life and early infancy.

It is not yet known whether this process plays a significant role in

human sexual behavior, although evidence from other mammals tends to

indicate a connection.

Estrogen has been found to increase the secretion of oxytocin and to increase the expression of its receptor, the oxytocin receptor, in the brain. In women, a single dose of estradiol has been found to be sufficient to increase circulating oxytocin concentrations.

Gynecological cancers

Estradiol

has been tied to the development and progression of cancers such as

breast cancer, ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer. Estradiol affects

target tissues mainly by interacting with two nuclear receptors called estrogen receptor α (ERα) and estrogen receptor β (ERβ). One of the functions of these estrogen receptors is the modulation of gene expression. Once estradiol binds to the ERs, the receptor complexes then bind to specific DNA sequences, possibly causing damage to the DNA and an increase in cell division and DNA replication. Eukaryotic cells respond to damaged DNA by stimulating or impairing G1, S, or G2 phases of the cell cycle to initiate DNA repair. As a result, cellular transformation and cancer cell proliferation occurs.

Other functions

Estradiol has complex effects on the liver. It affects the production of multiple proteins, including lipoproteins, binding proteins, and proteins responsible for blood clotting. In high amounts, estradiol can lead to cholestasis, for instance cholestasis of pregnancy.

Certain gynecological conditions are dependent on estrogen, such as endometriosis, leiomyomata uteri, and uterine bleeding.

Estrogen affects certain blood vessels. Improvement in arterial blood flow has been demonstrated in coronary arteries.

Biological activity

Estradiol acts primarily as an agonist of the estrogen receptor (ER), a nuclear steroid hormone receptor. There are two subtypes of the ER, ERα and ERβ, and estradiol potently binds to and activates both of these receptors. The result of ER activation is a modulation of gene transcription and expression in ER-expressing cells,

which is the predominant mechanism by which estradiol mediates its

biological effects in the body. Estradiol also acts as an agonist of membrane estrogen receptors (mERs), such as GPER (GPR30), a recently discovered non-nuclear receptor for estradiol, via which it can mediate a variety of rapid, non-genomic effects. Unlike the case of the ER, GPER appears to be selective for estradiol, and shows very low affinities for other endogenous estrogens, such as estrone and estriol.[40] Additional mERs besides GPER include ER-X, ERx, and Gq-mER.

ERα/ERβ are in inactive state trapped in multimolecular chaperone

complexes organized around the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90),

containing p23 protein, and immunophilin, and located in majority in

cytoplasm and partially in nucleus. In the E2 classical pathway or

estrogen classical pathway, estradiol enters the cytoplasm,

where it interacts with ERs. Once bound E2, ERs dissociate from the

molecular chaperone complexes and become competent to dimerize, migrate

to nucleus, and to bind to specific DNA sequences (estrogen response element, ERE), allowing for gene transcription which can take place over hours and days.

Given by subcutaneous injection in mice, estradiol is about 10-fold more potent than estrone and about 100-fold more potent than estriol.

As such, estradiol is the main estrogen in the body, although the roles

of estrone and estriol as estrogens are said not to be negligible.

Biochemistry

Human steroidogenesis, showing estradiol at bottom right.

Biosynthesis

Estradiol, like other steroid hormones, is derived from cholesterol. After side chain cleavage and using the Δ5 or the Δ4- pathway, androstenedione

is the key intermediary. A portion of the androstenedione is converted

to testosterone, which in turn undergoes conversion to estradiol by

aromatase. In an alternative pathway, androstenedione is aromatized to estrone, which is subsequently converted to estradiol via 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD).

During the reproductive years, most estradiol in women is

produced by the granulosa cells of the ovaries by the aromatization of

androstenedione (produced in the theca folliculi cells) to estrone,

followed by conversion of estrone to estradiol by 17β-HSD. Smaller

amounts of estradiol are also produced by the adrenal cortex, and, in men, by the testes.

Estradiol is not produced in the gonads only, in particular, fat cells produce active precursors to estradiol, and will continue to do so even after menopause. Estradiol is also produced in the brain and in arterial walls.

In men, approximately 15 to 25% of circulating estradiol is produced in the testicles.

The rest is synthesized via peripheral aromatization of testosterone

into estradiol and of androstenedione into estrone (which is then

transformed into estradiol via peripheral 17β-HSD). This peripheral aromatization occurs predominantly in adipose tissue, but also occurs in other tissues such as bone, liver, and the brain. Approximately 40 to 50 µg of estradiol is produced per day in men.

Distribution

In plasma, estradiol is largely bound to SHBG, and also to albumin. Only a fraction of 2.21% (± 0.04%) is free and biologically active, the percentage remaining constant throughout the menstrual cycle.

Metabolism

Inactivation of estradiol includes conversion to less-active

estrogens, such as estrone and estriol. Estriol is the major urinary metabolite. Estradiol is conjugated in the liver to form estrogen conjugates like estradiol sulfate, estradiol glucuronide and, as such, excreted via the kidneys. Some of the water-soluble conjugates are excreted via the bile duct, and partly reabsorbed after hydrolysis from the intestinal tract. This enterohepatic circulation contributes to maintaining estradiol levels.

Estradiol is also metabolized via hydroxylation into catechol estrogens. In the liver, it is non-specifically metabolized by CYP1A2, CYP3A4, and CYP2C9 via 2-hydroxylation into 2-hydroxyestradiol, and by CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2C8 via 17β-hydroxy dehydrogenation into estrone, with various other cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and metabolic transformations also being involved.

Estradiol is additionally conjugated with an ester into lipoidal estradiol forms like estradiol palmitate and estradiol stearate to a certain extent; these esters are stored in adipose tissue and may act as a very long-lasting reservoir of estradiol.[57][58]

Excretion

Levels

Estradiol levels across the menstrual cycle in 36 normally cycling, ovulatory women, based on 956 specimens. The horizontal dashed lines are the mean integrated levels for each curve. The vertical dashed line in the center is mid-cycle.

Levels of estradiol in premenopausal women are highly variable

throughout the menstrual cycle and reference ranges widely vary from

source to source.

Estradiol levels are minimal and according to most laboratories range

from 20 to 80 pg/mL during the early to mid follicular phase (or the

first week of the menstrual cycle, also known as menses).

Levels of estradiol gradually increase during this time and through the

mid to late follicular phase (or the second week of the menstrual

cycle) until the pre-ovulatory phase.

At the time of pre-ovulation (a period of about 24 to 48 hours),

estradiol levels briefly surge and reach their highest concentrations of

any other time during the menstrual cycle.

Circulating levels are typically between 130 and 200 pg/mL at this

time, but in some women may be as high as 300 to 400 pg/mL, and the

upper limit of the reference range of some laboratories are even greater

(for instance, 750 pg/mL).

Following ovulation (or mid-cycle) and during the latter half of the

menstrual cycle or the luteal phase, estradiol levels plateau and

fluctuate between around 100 and 150 pg/mL during the early and mid

luteal phase, and at the time of the late luteal phase, or a few days

before menstruation, reach a low of around 40 pg/mL.

The mean integrated levels of estradiol during a full menstrual cycle

have variously been reported by different sources as 80, 120, and

150 pg/mL.

Although contradictory reports exist, one study found mean integrated

estradiol levels of 150 pg/mL in younger women whereas mean integrated

levels ranged from 50 to 120 pg/mL in older women.

During the reproductive years of the human female, levels of

estradiol are somewhat higher than that of estrone, except during the

early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle; thus, estradiol may be

considered the predominant estrogen during human female reproductive

years in terms of absolute serum levels and estrogenic activity.

During pregnancy, estriol becomes the predominant circulating estrogen,

and this is the only time at which estetrol occurs in the body, while

during menopause, estrone predominates (both based on serum levels). The estradiol produced by male humans, from testosterone, is present at serum levels roughly comparable to those of postmenopausal women (14–55 versus <35 2-="" 4-fold="" 70-year-old="" a="" also="" approximately="" are="" been="" compared="" concentrations="" estradiol="" has="" higher="" if="" in="" it="" levels="" man.="" man="" ml="" of="" p="" pg="" reported="" respectively="" that="" the="" those="" to="" woman="">

Measurement

In women, serum estradiol is measured in a clinical laboratory and reflects primarily the activity of the ovaries. The Estradiol blood test measures the amount of estradiol in the blood. It is used to check the function of the ovaries, placenta, adrenal glands. This can detect baseline estrogen in women with amenorrhea

or menstrual dysfunction, and to detect the state of hypoestrogenicity

and menopause. Furthermore, estrogen monitoring during fertility therapy

assesses follicular growth and is useful in monitoring the treatment.

Estrogen-producing tumors will demonstrate persistent high levels of

estradiol and other estrogens. In precocious puberty, estradiol levels are inappropriately increased.

Ranges

Individual

laboratory results should always been interpreted using the ranges

provided by the laboratory that performed the test.

Reference ranges for the blood content of estradiol during the menstrual cycle

In the normal menstrual cycle, estradiol levels measure typically

<50 200="" a="" again="" and="" at="" briefly="" development="" drop="" during="" end="" estradiol="" follicular="" for="" is="" levels="" luteal="" menstrual="" menstruation="" ml="" nbsp="" of="" ovulation="" p="" peak.="" peak:="" pg="" phase="" pregnancy.="" rise="" second="" the="" their="" there="" to="" unless="" with="">

During pregnancy, estrogen levels, including estradiol, rise steadily toward term. The source of these estrogens is the placenta, which aromatizes prohormones produced in the fetal adrenal gland.

Medical use

Estradiol is used as a medication, primarily in hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms as well as transgender hormone replacement therapy.

Chemistry

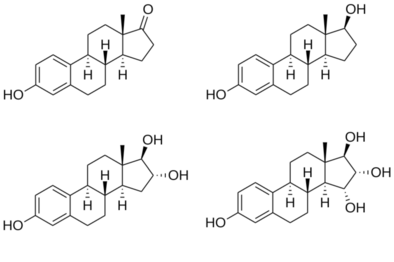

Estradiol is an estrane steroid. It is also known as 17β-estradiol (to distinguish it from 17α-estradiol) or as estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol. It has two hydroxyl groups, one at the C3 position and the other at the 17β position, as well as three double bonds in the A ring.

Due to its two hydroxyl groups, estradiol is often abbreviated as E2.

The structurally related estrogens, estrone (E1), estriol (E3), and estetrol (E4) have one, three, and four hydroxyl groups, respectively.

History

The discovery of estrogen is usually credited to the American scientists Edgar Allen and Edward A. Doisy. In 1923, they observed that injection of fluid from porcine ovarian follicles produced pubertal- and estrus-type changes (including vaginal, uterine, and mammary gland changes and sexual receptivity) in sexually immature, ovariectomized mice and rats. These findings demonstrated the existence of a hormone which is produced by the ovaries and is involved in sexual maturation and reproduction.

At the time of its discovery, Allen and Doisy did not name the hormone,

and simply referred to it as an "ovarian hormone" or "follicular

hormone"; others referred to it variously as feminin, folliculin, menformon, thelykinin, and emmenin. In 1926, Parkes and Bellerby coined the term estrin to describe the hormone on the basis of it inducing estrus in animals. Estrone was isolated and purified independently by Allen and Doisy and German scientist Adolf Butenandt in 1929, and estriol was isolated and purified by Marrian in 1930; they were the first estrogens to be identified.

Estradiol, the most potent of the three major estrogens, was the last of the three to be identified. It was discovered by Schwenk and Hildebrant in 1933, who synthesized it via reduction of estrone. Estradiol was subsequently isolated and purified from sow ovaries by Doisy in 1935, with its chemical structure determined simultaneously, and was referred to variously as dihydrotheelin, dihydrofolliculin, dihydrofollicular hormone, and dihydroxyestrin. In 1935, the name estradiol and the term estrogen were formally established by the Sex Hormone Committee of the Health Organization of the League of Nations;

this followed the names estrone (which was initially called theelin,

progynon, folliculin, and ketohydroxyestrin) and estriol (initially

called theelol and trihydroxyestrin) having been established in 1932 at

the first meeting of the International Conference on the Standardization

of Sex Hormones in London. Following its discovery, a partial synthesis of estradiol from cholesterol was developed by Inhoffen and Hohlweg in 1940, and a total synthesis was developed by Anner and Miescher in 1948.